Turner and the Thames: Will Gompertz reviews show at the house designed by the artist ★★★★☆

- Published

Apparently, the great British romantic painter JMW Turner (1775-1851) once said if he could have his life again he would have been an architect: a statement that is as good an argument as any I've heard against reincarnation.

That's not to say London's finest landscape artist couldn't have become a decent architect from a technical point of view. He knew his way around a set of plans having been apprenticed to an architect in his early teens, and would regularly include grand buildings in his paintings.

But design is only a small part of the art of architecture.

The real work is done in wooing and cajoling clients, compromising to accommodate their wishes, and working within a budget that is typically about as fit for purpose as an honest thief.

The famously irascible, opinionated, singular genius that was the barber's son from Covent Garden would have fallen out with more customers than the Duke and Duchess of Sussex have with family members. The chances of him running a successful architectural practice would have been zero, added to which we wouldn't have his extraordinary art to enjoy.

There is one place, though, where, for the first time since 1826, we can have a glimpse into a world where Turner the would-be architect and Turner the supreme painter of light and atmosphere, coexist.

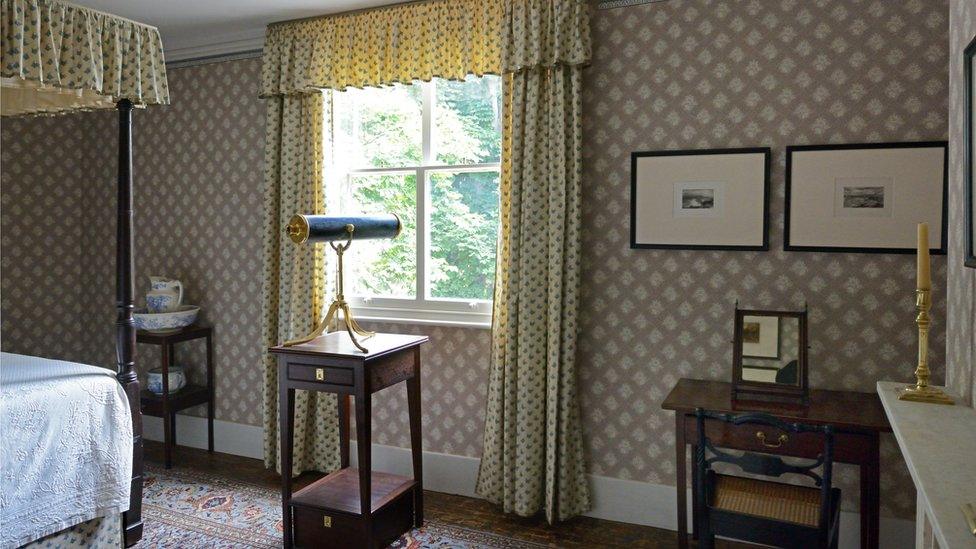

It involves a trip to suburban Twickenham in south-west London to visit a small but perfectly formed Georgian house that Turner himself designed between 1807-13 (with a little help from his friend, the renowned architect, Sir John Soane).

The great landscape artist designed this small villa, Sandycombe Lodge, near the Thames at Twickenham between 1807-13

William Daniell's etching of JMW Turner when he was 25 years old, is at the artist's house

Sandycombe Lodge is his one and only realised building - or three-dimensional artwork as those wishing to elevate its status might say - and as such gives us two insights. Firstly, Turner's architectural tastes were as conservative as his paintings were radical. And secondly, he was, at heart, a modest man.

It is a bijou property on what was a sizeable plot, which the 32-year-old Turner bought to build his bolthole from the hurly burly of central London life.

He was already a very successful artist with a pad in Harley Street to which he had attached his own commercial art gallery. He liked the idea of owning a des-res in what the poet James Thomson described as "the matchless vale of the Thames" - the riverside area seen from Richmond Hill taking in Kew, Twickenham, Isleworth and Richmond.

It was the Cotswolds of the day, the trendy place where the rich and famous would "weekend" and fill their palatial houses with glamorous guests. Turner being Turner and a contrary sort of fellow, went tiny where others - such as his old Royal Academy president Sir Joshua Reynolds - went very large.

Turner wasn't interested in impressing anybody, he was interested in the light of the Thames, a river to which he had spent his life living in close proximity.

He'd invite a few mates to stay (including, somewhat surprisingly, the Duc d'Orléans, later Louis Philippe, King of France), take them fishing, ask them to join his "Pic-nic-Academical Club", and discuss poetry.

Turner designed the villa so he could see the river from this bedroom window

There is no evidence he painted with oils there, but he certainly sketched and probably went out on his specially made boat-cum-studio to paint in watercolours.

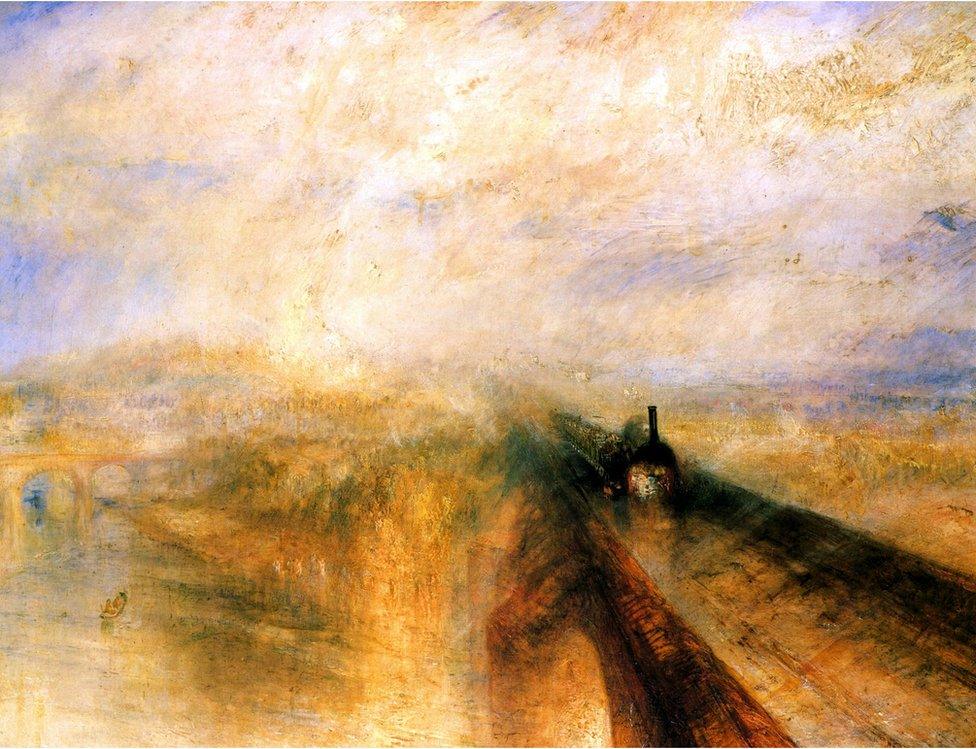

What is without doubt is his lifelong artistic relationship with the River Thames, an important motif most famously evident in his magnificent masterpiece Rain, Steam and Speed (1844).

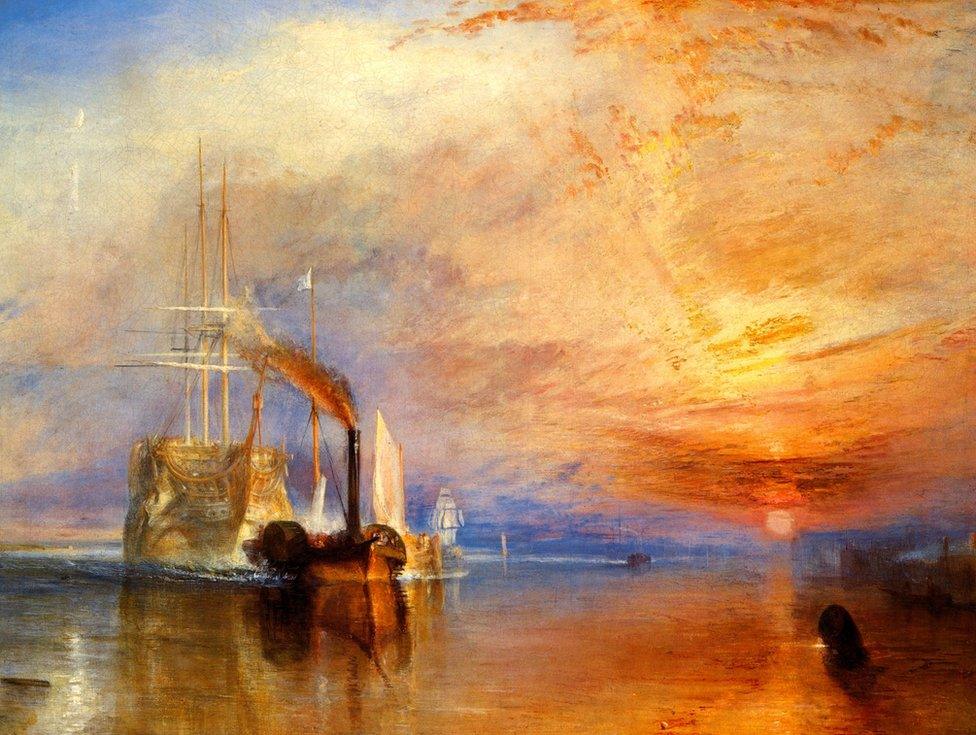

It is, along with The Fighting Temeraire (1839), a painting that cements Turner as one of the most popular artists in the UK and beyond. They are both late works but you can see their origins in some earlier oil sketches he produced while living in Isleworth, which have been borrowed from the Tate Gallery and are now presented in a pocket-sized exhibition at Sandycombe Lodge.

Turner's Rain, Steam, and Speed, 1844, isn't in the show (along with The Fighting Temeraire), but you can see how they were influenced by the early sketches

The Fighting Temeraire, 1839 (not in the show), shows the final journey of this important warship, as it's towed along the Thames to Rotherhithe, where it was to be scrapped

It is the first time since the artist sold his Twickenham home nearly 200 years ago that any of his original paintings have hung on its walls. They are displayed in an upstairs guest bedroom, which is not very big, but then nor are the sketches.

There are five paintings in total, all on mahogany, one more warped than a 12 inch vinyl left out in the sun.

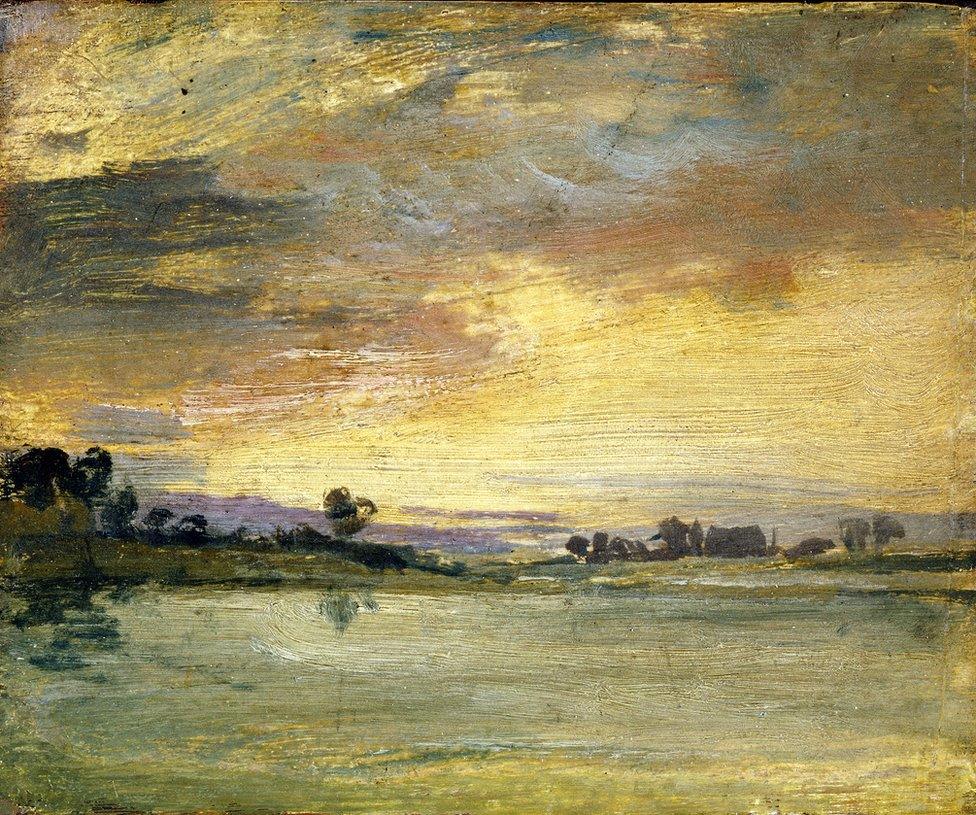

They are described as "experimental, private works", which is code for not first-rate. No matter, they are fascinating to see.

The largest, Walton Reach (1805), hangs over the fireplace. It is the least good of those on show, with a vertical clump of black/grey cloud hovering like a spaceship in the middle of the sky.

Walton Reach, 1805, is one of the five rarely shown oil sketches that the Tate has loaned to Turner's House for this exhibition

Constable would have laughed himself silly at his great rival's ham-fisted attempt to paint a meteorological effect. But then his eyes would have glanced to the left of the painting and seen Turner bang in form as river morphs into trees that lead to a heavenly pink sky obscuring a sun behind.

There's a lovely, quickly painted, sketch The Thames near Windsor (1807), which Cézanne would have admired for its palette and abstracted simplicity.

Another, On the Thames (1807), also has a proto-Impressionist feel as Turner captures light effects in real time.

The Thames near Windsor c.1807

On the Thames c.1807, like the other four works, was selected by Turner's House for depicting scenes close to the artist's house near the river

The two stand-out sketches are Sunset on the River (1805), which is beautiful, and Windsor Castle from the River (1807), which benefits from having been primed with white paint giving it a lustre and luminosity the others don't share. Both are clearly a foretaste of what is to come in Turner's later years.

Sunset on the River is an obvious precursor to Turner's Fighting Temeraire with the sun going down behind thin orange clouds, evoking the romantic nostalgia that makes his later masterpiece such a mesmerising artwork.

Windsor Castle from the River points towards Rain, Steam and Speed: a ghostly structure barely visible in the background, partially hidden behind the atmospheric effects of Thames water merging into hazy cloud.

Bathed in light, Turner's Sunset on the River, 1805, is a forerunner of his Fighting Temeraire

Windsor Castle from the River, 1807

The sketches are not masterpieces, nobody is going to pay millions of pounds to own them or view them (£8 entry to the house and exhibition), but they are well worth seeing: on their own terms and also as a way of understanding how Turner worked and developed as an artist. That they are in the house he designed for himself is an added bonus: there's a lot to be said for quiet modesty in this overwrought, over-excited century.

It was an escape for Turner then. It can be an escape for you now.

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter, external

- Published28 September 2019