Brit Awards 2020: Why weren't more women nominated?

- Published

Dua Lipa has called for better representation of women at the Brits

"Here's to more women on these stages, more women winning awards and more women taking over the world," said Dua Lipa, as she picked up best British female at the 2018 Brit Awards.

A year later, her wish had been granted. The number of women nominated in the three mixed-gender categories (best album, best single and best new act) had risen from four to 12. For the second time in Brits' history, female artists outnumbered men for the night's biggest prize, album of the year.

This year, though, it's a different story. The shortlist for best album is exclusively male; while only one woman - Mabel - has been nominated in categories where both men and women are eligible.

"How do they look at that list and go, 'Yeah, that's cool, let's go with that'?" asks the NME's editor, Charlotte Gunn. "I find it really strange."

Interestingly, the Brits seem to know something's amiss. As The Guardian pointed out, external, the press release announcing this year's nominees came with a footnote that explained: "The eligibility list has been compiled by the Official Charts Company and includes artists who have released product and enjoyed top 40 chart success. Record companies have had the opportunity to inform Brit Awards Ltd (BAL) of any eligible artists they wish to be added or inform BAL of any incorrect entries."

"In other words," wrote the paper's chief music critic, "don't blame us, it's the record companies who are at fault."

And it's true. If you look at the top 40 best-selling albums of 2019, only two were by British women - Jess Glynne (for a 2018 release) and Dua Lipa (for a 2017 release), both of which were ineligible for this year's Brits.

Mabel is the most successful female nominee at this year's Brit Awards

In the singles chart, Mabel's Don't Call Me Up was the only female solo record to make the top 10 - and duly receives a nod in the best single category (US star Miley Cyrus is also nominated as a featured artist on Mark Ronson's Nothing Breaks Like a Heart).

You could argue, as the permanently-reasonable denizens of Twitter have argued, that "women would be up for these prizes if their records had been good enough". And that's true to an extent: Adele, Emeli Sande, Dua Lipa, Little Mix and Jorja Smith have all won prizes in recent years.

But the harsh reality is that the pool of female talent is smaller, because the record industry is terrible at nurturing female artists.

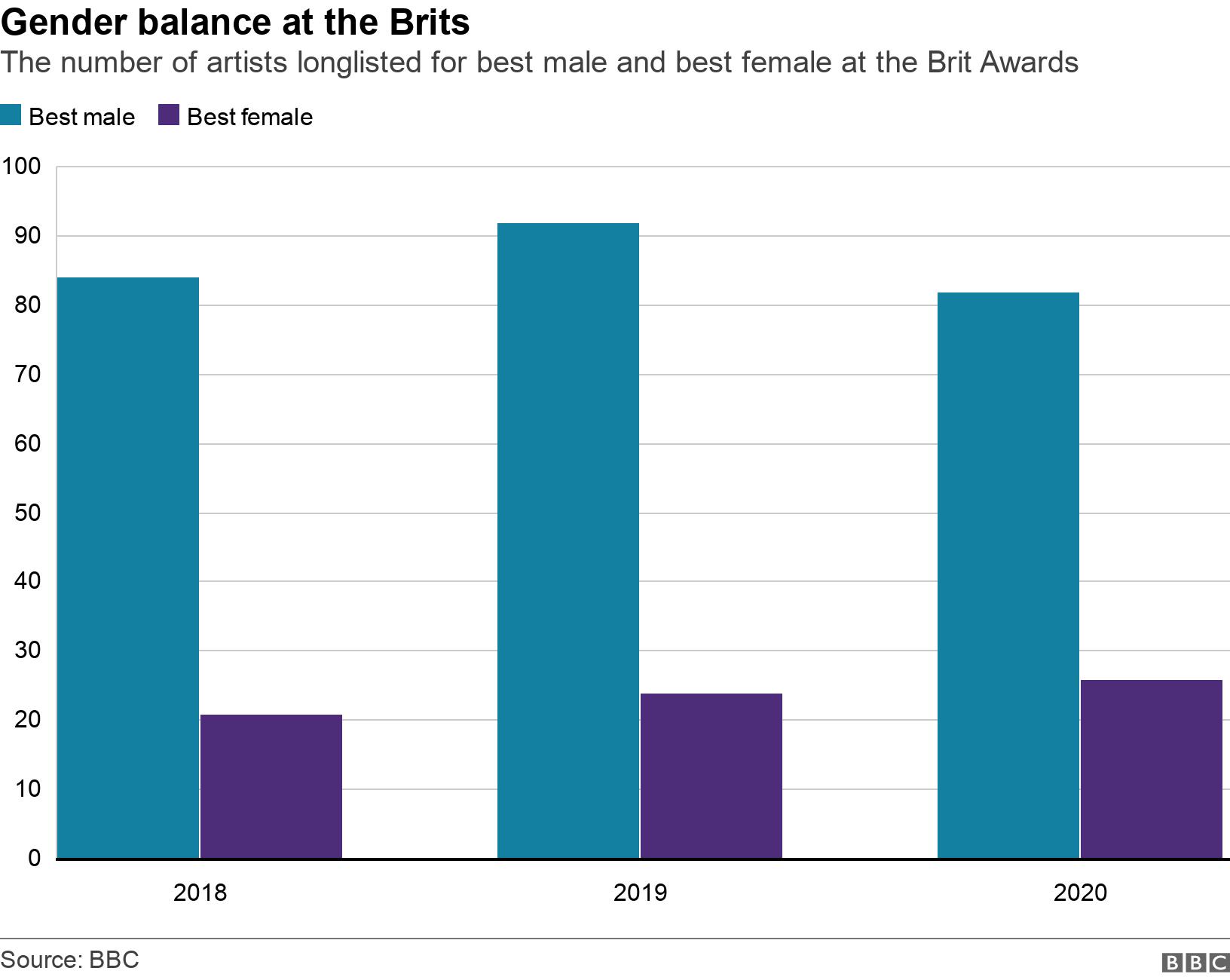

Need proof? Well, take a look at the number of artists who were put forward for the Brits' best male and best female prizes over the last three years.

Similarly, of the 193 albums submitted for consideration for this year's best album prize, only 35 were by women. So even though 49% of the Brits' voting academy is female, there's a huge imbalance in the records they get to choose from.

Why, then, is the music industry doing so poorly?

"Anecdotally, I've heard that labels are not too keen on signing and developing female talent because it costs more," says Rhian Jones, a contributing editor to Music Business Worldwide.

"There's stylists, there's make-up artists and the shows tend to be bigger productions. Whereas Lewis Capaldi can just get a guitar out, put a t-shirt on and everyone loves it."

Little Simz was frozen out of the Brit nominations despite releasing one of the year's most acclaimed albums

An underlying problem is that the upper ranks of the UK music industry are still dominated by men.

A 2016 study by UK Music revealed that women held just 30% of senior executive roles, despite making up more than half of entry-level positions. An updated version in 2018 didn't even break down the gender gap - simply stating there was a "lower number of females and males in senior posts" (UK Music was unable to share its latest data with the BBC upon asking).

'Change the criteria'

The result is that the "vast majority" of people who "sign and invest" in new artists are still men, says Jones, "and the trends suggest all these men are signing lots of other men".

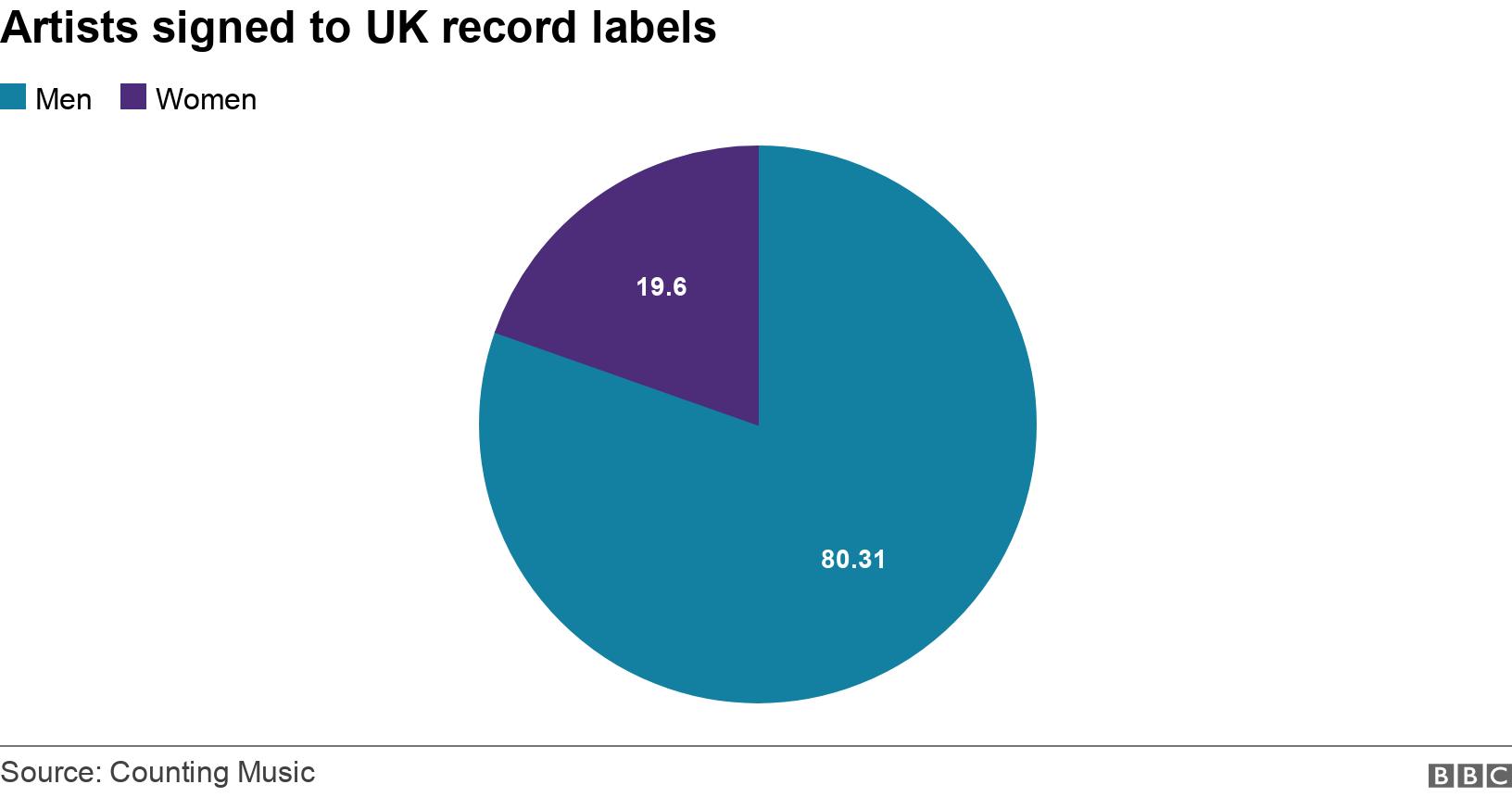

In fact, just 19% of the artists signed to record labels in the UK are women, according to research, external by music industry consultant Vick Bain.

Even when female acts do get signed, they face extra pressure, says rapper Little Simz.

"It's almost like you've got one album to get it in the bag, and if you don't people move on," she told the BBC last year. "Which is sad, because I don't think you're always going to get it right that one time.

"My first album wasn't my breakthrough. If I'd been signed to a major record label, that might have been the end of my career."

The star's latest record, Grey Area, was nominated for a Mercury Prize last year and featured on several critics' Best Of 2019 lists; but was considered ineligible for the Brits because it didn't crack the Top 40.

"The Brits need to have a look at their eligibility criteria, because [success] isn't necessarily about record sales any more," says Jones.

She suggests that organisers could consider factors such as critical acclaim, social media following, and live ticket sales "because that's where acts are making money and breaking out these days".

"The system has completely changed and I don't think the Brits' eligibility criteria has changed with it," she observes.

Bebe Rexha's Women In Harmony events aim to tackle the music industry's gender imbalance

In recent years, several initiatives have sprung up to address the industry's inequality - the most high-profile of which is Bebe Rexha's Women In Harmony programme, which hosts dinners where female artists, songwriters and producers can foster links and provide support.

"The way we make [things] better is we make more room for ourselves," Rexha told the BBC.

"How do you do that? You build relationships. You support other females. You call each other, you have hits with each other, you collaborate with each other.

"I want to support artists that are coming into the industry - because I feel like I didn't get support when I came in."

'Trying to be woke'

In the UK, the PRS Foundation runs a Women In Music fund, and spearheads the Keychange initiative, which has seen more than 300 festivals and music organisations pledge to achieve a 50/50 gender balance by 2022.

"We have found that positive action is essential if we are serious about creating equal opportunities as an industry," says Maxie Gedge, who runs the scheme.

"We recognise this cannot be done by any one organisation alone so we continue to support and encourage everyone to collaborate, take responsibility and make change wherever they can. Artists like Freya Ridings and Joy Crookes who triumph despite adversity give us hope, whilst we value important allies such as Sam Fender and The 1975."

The NME is also playing a role with a series of free concerts under the banner "Girls At The Front".

"They're small shows with two female bands or artists, helping to showcase female talent," says Gunn.

"In all honesty, some people thought it was tokenistic, and the NME 'trying to be woke' but we need more things like that - more people getting behind new artists - and then hopefully in 10 years, maybe sooner, it will genuinely be a fair, balanced, level playing field."

So what does this mean for the Brits? Organisers will point to the fact that this year is a blip, while the overall trend is for better representation of women; and that all three of the Rising Star nominees were female artists (the winner, Celeste, will also get to perform at the ceremony).

But Gunn warns against complacency.

"I think we do need to worry about it," she says. "After the #MeToo movement, everybody was suddenly very conscious of female representation and now it's like, 'OK, we did our bit and we can all move on'.

"But it's a systemic problem that is going to take a long time to change. And really, from the top down, the Brits should have had people going, 'Is this fair? Is this representative? Maybe we should check ourselves here.'"

Full disclosure: The author of this article is a member of the Brits' academy.

Follow us on Facebook, external, or on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published11 January 2020

- Published19 February 2019

- Published5 November 2019