Coronavirus and a fake news pandemic

- Published

Fake news is spread through public and private forums

I suppose you could call it a "bombshell" tweet.

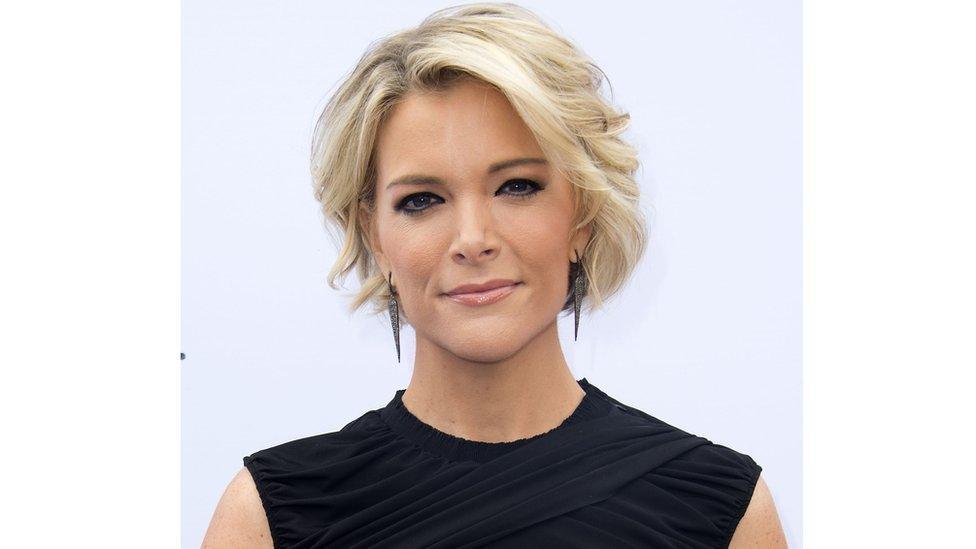

Megyn Kelly is probably the most famous female journalist in America today (though Oprah Winfrey might object). Kelly was for years an anchor on Fox News; her dealings with its boss, the sexual predator Roger Ailes, is the subject of a recent film called, yes, Bombshell. Charlize Theron played Kelly.

On Thursday morning, Kelly tweeted: "I'm so frustrated right now… that we can't trust the media to tell us the truth without inflaming it to hurt Trump… that Trump has misled so many times we no longer know when to trust his word… that even I as a journalist am not sure where to turn for real info on COVID".

If trust in the media is your concern, perhaps working for Fox News wasn't the smartest place to start, as many of Kelly's nearly 20,000 respondents pointed out. I'm not one to encourage a social media pile-on; indeed I hardly tweet these days, so corrupting has that platform become for our public domain. But everything about Kelly's tweet is at once remarkable and awful.

Former Fox News anchor, Megyn Kelly, has 2.4m followers on Twitter

It has become fashionable to panic about fake news whenever huge stories emerge. A few days ago, 10 Downing Street brought in the UK bosses of major technology firms to make clear they have a role in fighting misinformation.

The evidence suggests there is some of it about. Claims that it is a chemical weapon, a giant hoax, or cured by garlic have all probably been seen by millions. But as ever with the now common panics about fake news, things are much more complicated than generally understood.

Much of the fake news is spreading through private forums - whether chat rooms online or on WhatsApp, a platform for encrypted messages. Some of these messages clearly come from disreputable websites, such as the disgraceful InfoWars, which has linked the response to coronavirus to some kind of malign plot by Bill Gates. If you look to Infowars for reliable information, your judgement isn't up to much.

Moreover, a significant chunk of the supposedly fake news is actually just badly edited material which is then used on social media to confirm the prejudices of those who see it. British Prime Minister Boris Johnson went on ITV's This Morning, and talked about the need for a stiff upper lip. He went on to make clear the latest medical advice and legitimate concerns. But a clip went viral of the first half of his comments, denuded of that context. Cue outrage on - where else but - Twitter. That's not fake news; it's just mischievous editing, and tedious confirmation bias.

Sadly, it is a regular feature of President Trump's reign that he himself spouts misinformation, while castigating "the fake news media, external and their partner, the Democrat Party". In this pandemic, he has excelled himself at that, particularly at the start. I note Kelly accuses him of misleading people rather than lying. That her claim is uncontroversial shows we've reached a grim place in the information age.

Perhaps the biggest hoax within the fake news panic, however, is that this shows you can't trust the media. On the contrary - and this is what makes Kelly's tweet so dispiriting - this crisis has proved exactly how much you can trust the media. There is a clear dichotomy, between authoritative, very widely trusted sources such as the BBC and CNN, and crackpot conspiracy theory sites like InfoWars.

In times of crisis, audiences are in fact flocking to what has been disparagingly called the "mainstream media". Traffic to the BBC News website is surging to extraordinary levels. Over the past month, 12 February to 11 March, there have been over 575m page views globally to stories about coronavirus. People want trusted information and - unlike Megyn Kelly - know where to turn.

Conspiracies abound online of course. Alas something about public health scares make them particularly adept at inspiring conspiracy theories. My theory is that that "something" is a combination of the public's anxiety about their health, and that of loved ones, and the fact that widespread knowledge of the science of viruses is limited. It's spookily complicated stuff - and people are dying. Help!

Fake news and conspiracies at a time like this are so obviously reprehensible that the more interesting issue is the challenge to news itself. In periods of public panic, the role of journalism can at times - and only at times - resemble stenography. Whereas most of the time journalists think of themselves as being in opposition to governments, when the public are scared, journalists and government have incentives that are more aligned: passing on the best information.

In doing this, journalists face a secondary challenge. If you give over the airwaves to, say, Boris Johnson, and let him look and sound presidential behind a podium, you might be doing important work of letting his information reach the public. But you potentially slip into what feels like propaganda. Therefore the effect, of presenting him as a wartime leader, is something impartial journalists committed to applying scrutiny to power will resile from.

The UK's Prime Minister Boris Johnson speaks during a press conference about coronavirus inside 10 Downing Street

These are the deep, complex issues with which journalists, who are having a decent crisis, must grapple. Megyn Kelly might be right to say that American media are so inflamed they can't be trusted (though that's unfair on some). She is right to imply that Trump is not always wedded to accuracy. If she doesn't know where to turn for real info, however, she can't be looking very hard.

If you're interested in issues such as these, please follow me on Twitter, external or Facebook, external; and also please subscribe to The Media Show podcast, external from Radio 4. I'm grateful for all constructive feedback. Thanks.

- Published28 September 2020

- Published13 March 2020

- Published25 January 2022

- Published22 February 2022