Brian Cox and Adele's producer Paul Epworth discuss music and the cosmos

- Published

Paul Epworth and Brian Cox discuss zero-gravity and space exploration

Paul Epworth is behind some of the biggest pop records of the last 20 years, from Adele's Rolling in the Deep to Florence and the Machine's Rabbit Heart (Raise It Up).

Along the way he's worked with Rihanna, Stormzy, Sir Paul McCartney, Coldplay and U2 - and he won an Oscar for co-writing the Bond theme Skyfall.

But now, after years behind the scenes, the producer is releasing his first solo album. Voyager, a journey into deep space, fuses influences from classic sci-fi movies with his love of musical explorers like David Bowie, George Clinton, Wendy Carlos and Jean-Michel Jarre.

"It's a sort of '70s space concept album, which is a bit of a cliché as a producer - to make something that ostentatious and overblown," he told BBC News.

"But I've tried to frame it in a modern way, so I've got some great singers and rappers on it."

The record sees guest vocals from the likes of Jay Electronica, Ty Dolla $ign, Vince Staples, Lianne La Havas and Kool Keith. But, more importantly, it allowed Epworth to indulge his passion for space travel and astrophysics - as well as a habit for collecting ancient, analogue synths at his studio in London's Crouch End.

He traces his interest in science back to his father's work in developing optical fibres. Yet he remains endlessly curious about life, the universe and everything.

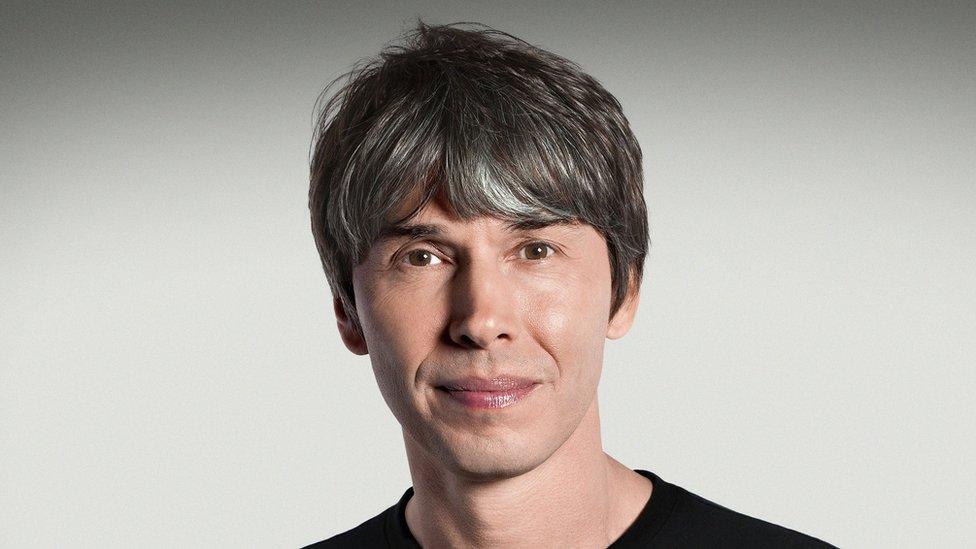

To celebrate the record's release, Epworth hooked up with Professor Brian Cox - the prominent physicist and former keyboard player for '90s dance act D:Ream - to ask some of the questions that occurred to him while making the album.

Paul Epworth: When I began working on a record about space, little did I think I would be sitting here with you. Obviously you started in music as well, so what prompted you to make that shift into this love of the cosmos and astrophysics?

Brian Cox: To be honest, my first interest was astronomy. As far back as I can remember. I just liked looking at the stars.

I've thought about it a lot - what was it that made a seven-year-old become interested in stars? And I suppose it goes all the way back to looking forward to Christmas when you're six years old... and I think I began to associate it with the constellations. My dad once said to me 'There's Orion, it's the easiest constellation to see.' And I noticed that it was in the autumn and the winter when I'd start seeing Orion over our back garden.

But I also remember really vividly Star Wars and Star Trek in general. So I also liked science fiction for some reason and I conflated it all together. Space became this idea, which was part escapism, part Star Wars [and] part astronomy. Music was almost a distraction!

What is the connection for you between music and the cosmos? Is there a piece of music that brings the two together?

Vangelis's theme for Carl Sagan's Cosmos. To this day, when that music starts, it's a shiver. It takes me right back to being 11 years old and looking at the sky. It is really powerful.

I've actually been involved in the last few years with some attempts to match classical music to the ideas that are raised in astronomy and cosmology. We live in a potentially infinite universe which, to me, raises questions about our mortality about our fragility.

What does it mean to live these small, finite and in some sense insignificant lives in this potentially eternal and potentially infinite universe? Those are emotional questions, they're deeply human questions, and they're questions that have motivated a great deal of art and music.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

I was reading a book recently by a guy called Itzhak Bentov called Stalking the Wild Pendulum, which is about the mechanics of consciousness. He talks about all matter vibrating - and of course vibration is the way every musical instrument generates noise. It got me thinking about how all these things fit together...

There's an interesting point there, which is that music is a product of consciousness and intelligence. And if you think about what we are - how it can be that some atoms that have been around since the Big Bang... essentially be able to start thinking and create music?

That's a remarkable thing. I think it was Richard Feynman who said "Human beings are atoms, that can contemplate atom." And part of those atoms' response to this remarkable phenomenon is to make music as part of the exploration of what that means. I find that remarkable.

There's a theory that the universe is actually shaped like a doughnut. What are your thoughts on that?

The point is we don't know. All we can observe about the universe is the bit we can see, which is undoubtedly a small patch of what exists. At the moment it's just over 90 billion light years across, so it's a big bit, [and] that bit is flat, as far as we can tell.

But that's probably like saying "I've explored the region around my house and it's flat." And it's flat, even if you live on a big hill, because the curvature of the world is much bigger than the region around your house. That's probably what the universe is like.

It's almost incomprehensible, the scale of some of this stuff.

The distances... I mean, even the closest big galaxy to us is Andromeda which we can see with the naked eye, if there's no moon and it's very dark. And the light that enters your eye took two million years to journey to Earth. It's a remarkable feeling when you know that. Just to think, when those photons set off on their journey, there were no humans on the earth. We hadn't evolved.

This is why music and art is helpful because I can say these sentences and trot out these words, but how a person reacts to that is... It's a complex, personal thing. How do you feel about the idea that we were in a sea of [stars] and we can see two trillion galaxies? How does that make you feel? I don't know how that makes me feel actually.

Epworth and Adele won Oscars in 2013 for composing the theme to Skyfall

That's why it's so inspiring because there's infinite angles to it. As you've understood more about the cosmos, how has your relationship with music changed?

It's broadened, I think. When I first started getting into music I got Enola Gay by OMD and Hazel O'Connor's Eighth Day and I got into Kraftwerk. But over the last 10 to 15 years I've really got introduced to some of the great classical music from the turn of the 20th Century, and you find that increased harmonic complexity and richness.

I did a concert actually with the BBC, about Holst's The Planets, which everybody listens to at school. It's almost become a pop classic now, but actually at the time it was shocking harmonically and in the way that it's orchestrated. And if you strip away that familiarity, you realise that it's a tremendous achievement. So I like searching out that complexity.

It's interesting you say that, because it's something I [discovered] while making this record. Maybe it's humans trying to recreate the complexity of the night sky somehow within a musical form.

It's a good analogy actually, because Western music has got quite a limited scale. There's just the [notes on a] piano keyboard and that's it. But from those very simple rules, the complexity is almost limitless. And that's an analogy for, I think, the way that we see the the Universe.

So if you look at it now, 13.8 billion years after the Big Bang, it's tremendously complex - but the laws of nature that that underpin that appear, as we look deeper and deeper, to be simple.

Is the universe a hologram?

I read this amazing Neil deGrasse Tyson quote about how the particles in our bodies move at the speed of light, and obviously as you get closer to the speed of light time slows down. So are the particles in our bodies occupying the same place and time as they were in the Big Bang?

Yeah, that's true. If you take the path of a photon that was released shortly after the Big Bang, and has travelled across the universe at the speed of light for 13.8 billion years or so, from our perspective - and say you'd carried a clock with you - how much time would you have experienced as a photon? Then you're right, the answer is zero.

That's one of the radical things about physics and cosmology - it forces us into these seemingly extremely counterintuitive positions.

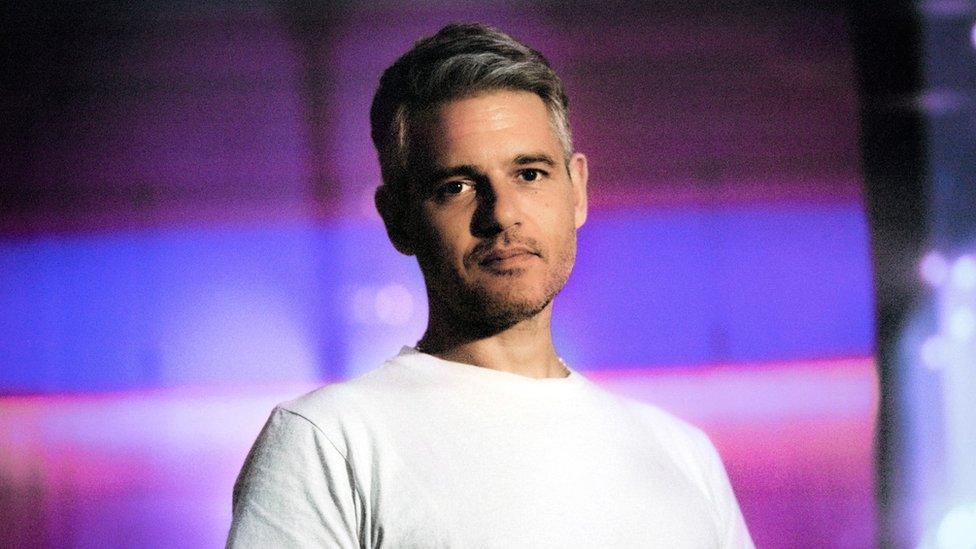

Epworth has been named producer of the year three times at the Brit Awards

Do you think new developments like quantum computing are going to make it easier for us to crack some of these puzzles?

Yes! Quantum computing has been a thing for a long time - that just in principle we could build these computers that are far more powerful than anything that we can build out of silicon. And harnessing that power is something that we're just about able to do now. We are building the first quantum computers and they're really primitive - they're like an abacus almost. But it didn't take as long to go from the first computers in the '40s to an iPhone or a Samsung.

And there's a suggestion that these machines will be able to simulate nature, much more precisely than we can at the moment, because all nature behaves in a quantum mechanical way. So we'll be able to explore places we can't go and [find out things like] what happens beyond the event horizon of a black hole?

Do you identify with space as a spiritual construct?

I never know what that word means - but it's certainly true [space] generates profound emotions. You've got to be in awe about the existence of the universe as a whole, and our existence within it. You're really missing the point if you're not astonished by that.

So, to come back to the music side of it: Life on Mars [by David Bowie] or Moon Safari [by Air]?

I have to say Life on Mars, because Hunky Dory is my favourite album. I love Rick Wakeman's piano playing on Life on Mars. If you're a musician and you try to play Life on Mars you realise that, while some of it's quite a standard chord sequence - I think it's actually the same as My Way - some of it is incredibly unusual and just shows you what instinctive genius Bowie was. What a writer. I love the whole album - although I love Air too.

Which do think you'll do first, go to Mars or have a safari on the moon?

I think the average person will get the chance to have a safari on the moon before they get to go to Mars. But I think someone might go to Mars before we can all have a moon safari.

Would you go?

I get asked that a lot. I think you have to have the right stuff - and I'm not sure I have the right stuff.

Follow us on Facebook, external, or on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published9 December 2019

- Published13 February 2015