Departures show: Why Britons make the great escape overseas

- Published

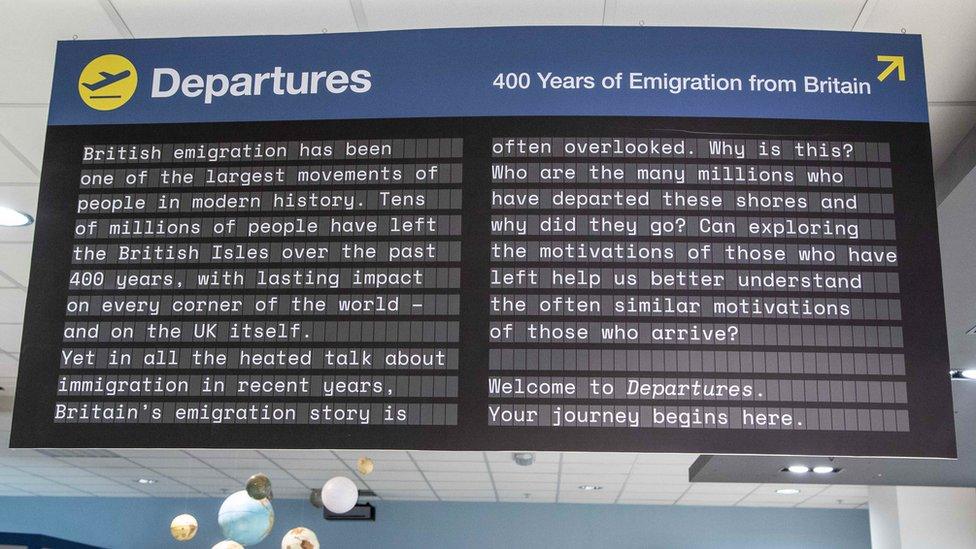

The exhibition layout mimics an airport departure lounge

Since London's Migration Museum opened its focus has mainly been migrants to Britain and what happened after they arrived. But its latest exhibition looks at something less familiar - how and why over the years huge numbers of Britons have emigrated permanently.

The exhibition Departures, which runs until June next year, has had to close for now due to the latest coronavirus restrictions in England. However, there will hopefully still be ample opportunity for the public to explore what Britons were keen to discover in the rest of the world, or perhaps so desperate to escape at home.

When the museum opened in 2017 it was tucked away in former London Fire Brigade engineering workshops. Shortly before the first lockdown it moved to what used to be an H&M fashion store inside the shopping centre in Lewisham, south London.

Those behind the museum hope the new location will make it more part of a community, one whose bustle and mixed ethnicity reflect the story the Migration Museum wants to tell of people arriving in the UK.

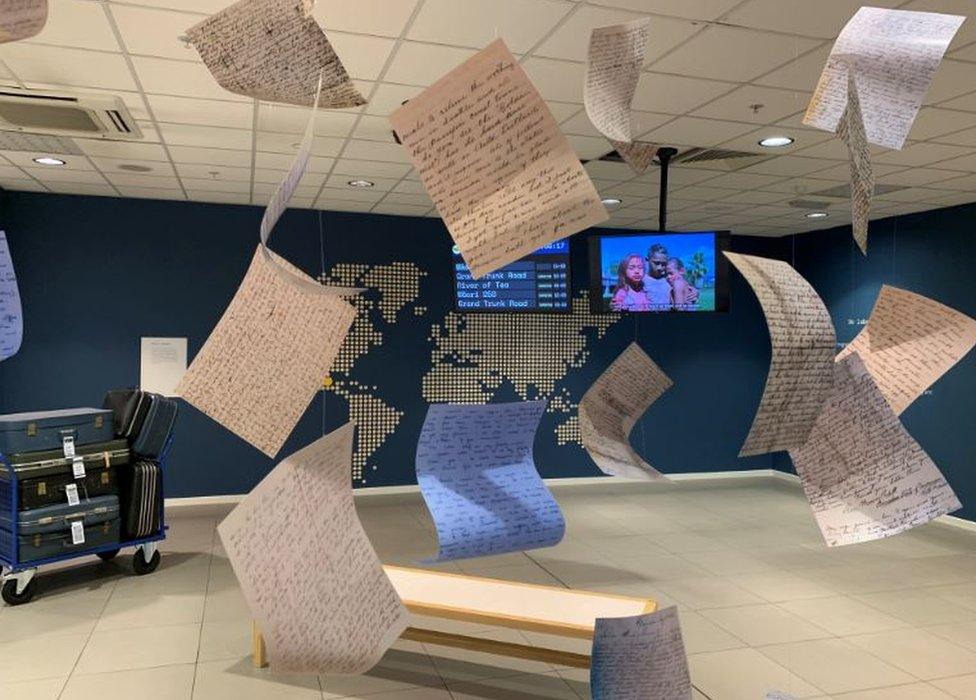

Postcards from those who've left "give human detail which I think can be touching," says one of the curators

Departures explores human traffic in the opposite direction. By some estimates there are around 75 million people in the world directly descended from people who left Britain to start their lives anew elsewhere. Some went willingly, others did not.

The exhibition layout mimics an airport departure lounge, leading to various Gates. Each Gate deals with one of the main reasons for people leaving Britain over the centuries.

But the curator Aditi Anand says motivations for going have often been complex.

"Historically our starting point, almost inevitably, is the story of the Mayflower which in 1620 took people fleeing religious intolerance from England to the new colonies in north America.

"We've labelled the first Gate you come to Escape/Dream. Sometimes people don't realise that many of the passengers 400 years ago in fact had already left Britain to go to Holland where their Puritan form of religion was accepted.

"But soon they worried that their children would grow up too Dutch and aspired to find a better and more English life across the Atlantic. It's an example of how people who left sometimes weren't only thinking of escape. They also imagined a better life far away.

"We chose the airport as a device to get a modern audience into the shoes of people who set off on an extraordinary range of journeys. If you think of the intense debate that has existed over immigration to the UK it may be odd that emigration is seldom discussed in the media or elsewhere. Yet the two are linked.

"I think most people will conclude that often the motivations are similar in whichever direction people are travelling."

Anand says an obvious reason for leaving Britain has always been to look for better economic opportunities. She mentions the so-called "Ten Pound Poms", who were given financial support to move permanently to Australia or New Zealand, beginning in the late 1940s. (Most passengers paid only a subsidised fare of £10 to sail from Britain.)

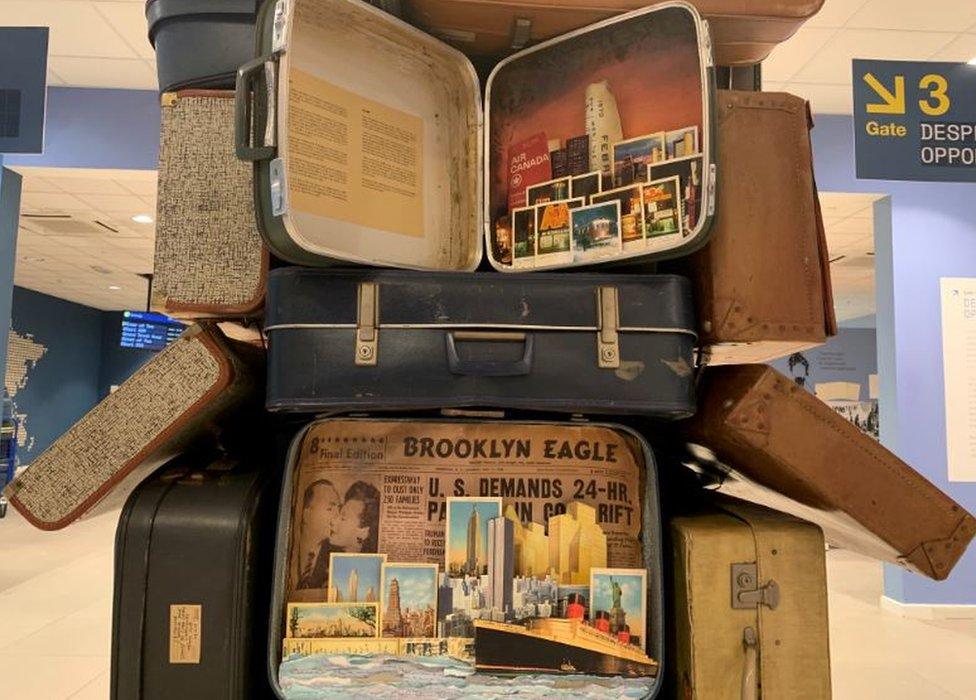

The exhibition uses mock airport Gates to illustrate reasons for leaving Britain

"But we also use a much later example of a young man leaving Northern Ireland in the 1980s to go to work in America. He wanted to escape the violence of the Troubles but also he saw no chance of economic advancement where he was. There are obvious parallels with people today who come to Europe to escape political and economic instability at home."

The new exhibition uses a mixture of artwork, audio recordings and visual displays to invite visitors to think about why people quit homes in Britain.

One Gate is called Forced to Leave. It recounts Britain's long and inglorious history of getting rid of unwanted citizens by forcibly transporting them thousands of miles across the world.

Letters from overseas tell individual stories

Dr Michaela Benson of Goldsmiths, University of London, has curated a modern section called Greetings from Europe. Her idea was simple: to ask Brits who've gone to live in Europe to send her a postcard explaining what their original motivation was.

Dr Benson says it's designed to give exhibition visitors more of an insight into individual lives.

Reasons given for moving elsewhere range from falling for a future spouse on a school exchange trip decades ago to finding a partner while studying recently in Finland. Some people just wanted a better job or more sunshine.

"It shows the random way big decisions can sometimes come in life. The exhibition has big themes like the growth of the British Empire but the postcards give human detail which I think can be touching."

Anand says a growing trend is re-pats, usually young people born in Britain who choose to "return home" to nations where their parents or grandparents were born. The re-pats may barely know their adopted country but feel they will be at home there and that they may have something to offer in return.

"It's something which only recently would have been uncommon. But I think it reflects a new era of movement that we're living in.

"People go back to, say, Ghana and may not even know if they plan to stay long-term. But they want to find new opportunities… and perhaps to find themselves. It's a modern thing to connect with another culture but they have feet in both worlds. It's a new imagining of migration."

Departures will be at the Migration Museum, ,south London until June 2021.