How Asian film is making moves to take over from Hollywood

- Published

Pawn, about a debt collector who adopts a little girl, opened this year's London Korean Film Festival

When Indonesian author Jesse Q Sutanto landed a book deal for her novel, Dial A for Aunties, she hadn't anticipated the film rights immediately being snapped up by Netflix.

The Jakarta-based author describes her debut as 'Crazy Rich Asians meets Weekend at Bernies'.

She says the tale - about a wedding photographer who accidentally kills off her blind date and then hides the body during an Indonesian society wedding - came along at just the right time.

"Everyone was in need to cheering up, because of lockdown. The over-the-top plot, and the ridiculousness of a dead body and a big wedding is such great escapism. Chinese-Indonesian weddings are amazing, they can have an average of 2,000 guests - my heroine has to hide the body with the help of her mum and aunties."

Sutanto will executive produce the film, which is directed by Nahnatchka Khan, who made Fresh off the Boat, a TV series about Taiwanese immigrants adjusting to life in the US.

Sutanto's debut novel, which will be published next year, is being turned into a Netflix film

But she believes the film deal would not have happened "without the success of Crazy Rich Asians".

Crazy Rich Asians, based on a novel by Kevin Kwan, was the first US blockbuster with an all-Asian cast. It made just under £200m worldwide.

Hot on its heels came the historic win for South Korean film Parasite, which was named best picture at the Oscars earlier this year.

So is the shift of cultural power finally moving East?

"Lots of issues are coming together in a perfect storm in 2020," explains Mike Goodridge, artistic director of Macao's International Film Festival and Awards, external, which holds its fifth edition in December.

"China is now officially the biggest film market in the world - there are 1.3 billion people there and that wipes out the US market by comparison. You're looking at gigantic-sized hits coming out of China - films coming close to making $1bn in China alone.

'More open to subtitles'

"But there's also a sea change. In the past, we've been at the mercy of what you could call American cultural imperialism - we all used to wait for the next Hollywood blockbuster. They made the movies and showed them throughout the world.

"But streaming services like Netflix and Amazon are about getting subscribers in each country. You can't just throw Marvel movies at that audience - you have to make local films and TV. They want their own stories.

"And so these US companies are putting money into content creation all over Asia, including a hub in Singapore."

Goodridge thinks chances are high that there will be another crossover hit from Asia.

"This shift has coincided with the pandemic. We're not seeing many Hollywood movies, as they have been delayed, so viewers who are at home are focused on a lot of TV or interesting foreign language stuff that we've never looked at before," he says, adding: "We're more open to subtitles."

South Korea, whose music industry has already successfully exported K-Pop artists such as BTS to a worldwide fan base, is in pole position to take advantage, following the success of Parasite, the first non-English language film to take top prize at the Academy Awards.

South Korean best picture winner Parasite has paved the way for future crossover hits

Darcy Paquet, subtitle translator for Parasite and the founder of koreanfilm.org, helped programme this year's London Korean Film Festival, external, which opened on 29 October with Korean box office hit Pawn.

Parasite's global success means two short films which made director Bong Joon-ho famous in his native Korea - 1994's Incoherence and 2004's Influenza - have received top-billing at the event.

"Of course, everything Bong Joon-ho makes will now get worldwide attention," Paquet predicts. "It's Bong's style that allowed him to access such a huge audience - but other Korean directors, like Park Chan-wook, have a growing international following."

"Korea has the highest cinema attendance in the world, per capita. It's a society that really loves film and their storytelling is sophisticated.

"We can expect other impressive Korean films to make an impact - and now Western audiences might be more willing to take a chance on them."

Such films are bringing into focus cultural values that may be unfamiliar to Western audiences.

"There's a strong emphasis on the family - and an individual's part within the family is a key part on how to relate to the character," says Paquet.

"Definitely in Korea - as well as in Japan and China - education, science and technology are really prized, and that's expressed in the films," she adds.

"And there's much less irony than in Hollywood stories - the emotions in their stories are expressed very directly and can be very intense."

But it is not always straightforward to export cultural values successfully to a Western audience.

"In China, there's a great sense of storylines," says Mike Goodridge. "They follow rules in society: in a story, if you commit a murder - no matter what the scenario - you'll have to serve your time.

"If you're used to the beats of Hollywood storytelling, you watch it thinking, 'there's no way they should be in prison!'. Their moral values are more reflective."

And that the misunderstanding can be mutual. "Crazy Rich Asians bombed in China," Goodridge points out.

Crazy Rich Asians was a major commercial hit for Hollywood in 2018. A sequel, China Rich Girlfriend, has been delayed because of the pandemic.

Nevertheless, given the success of Crazy Rich Asians elsewhere, as well as the popular appeal of films such as Lulu Wang's The Farewell, Hollywood seems convinced Asian American stories have potential for a wider audience.

It was recently announced that Killing Eve's Sandra Oh and Awkwafina will star in a Netflix comedy about warring sisters, while Adele Lim - who co-wrote Crazy Rich Asians - will work with the Japanese producer-director Hikari on the Richard Curtis romantic drama Lost for Words.

Lim has also co-written Disney's new animation, Raya and the Last Dragon, using the voices of Awkwafina and Kelly Marie Tran.

But does Asia even need Hollywood anymore?

"Vietnam, for example, has 100 million people, and like South Korea, Taiwan and New Zealand, they've handled the Covid-19 crisis well," says Vietnamese American Anderson Le.

Le is artistic director of this month's Hawaii international Film Festival, and co-founded the film studio East, which makes stories from across Vietnam and South East Asia.

"Half the population is under the age of 40," he explains.

"The cinemas are open, ticket sales are good, and because there are no competing films coming from Hollywood, audiences are watching some really good local films.

'I don't think countries like Vietnam, China and Korea even need to think about America now. They're like the Bollywood film industry in India, in that they want to reach their own first. Any other success elsewhere is just gravy to them."

But the area where Asia does want to make an impression, Le agrees, is at the Oscars - seizing the cultural cachet that a Hollywood award gives a homegrown film.

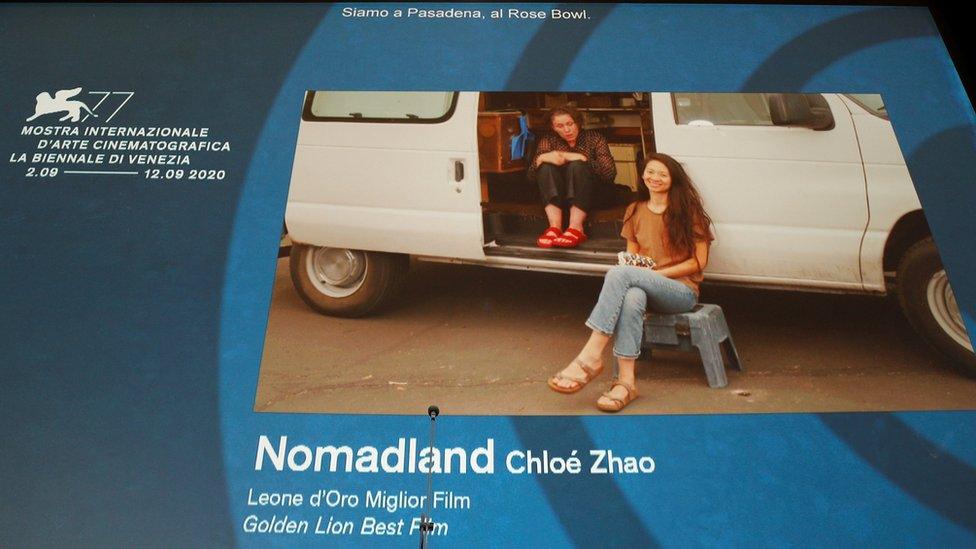

Nomadland, a drama by Chinese filmmaker Chloe Zhao, won the top prize at the 2020 Venice Film Festival and is tipped for Oscar glory

And in 2021, as long as the Academy Awards actually take place, Asia will once again have a significant stake.

The film Nomadland, starring Frances McDormand, is the current favourite for best picture. It's set entirely in the US - but its maker, Chloe Zhao, who may become only the second woman to win best director, was born and raised - in China.

- Published6 August 2020