How fact met fiction in Le Carré's secret world

- Published

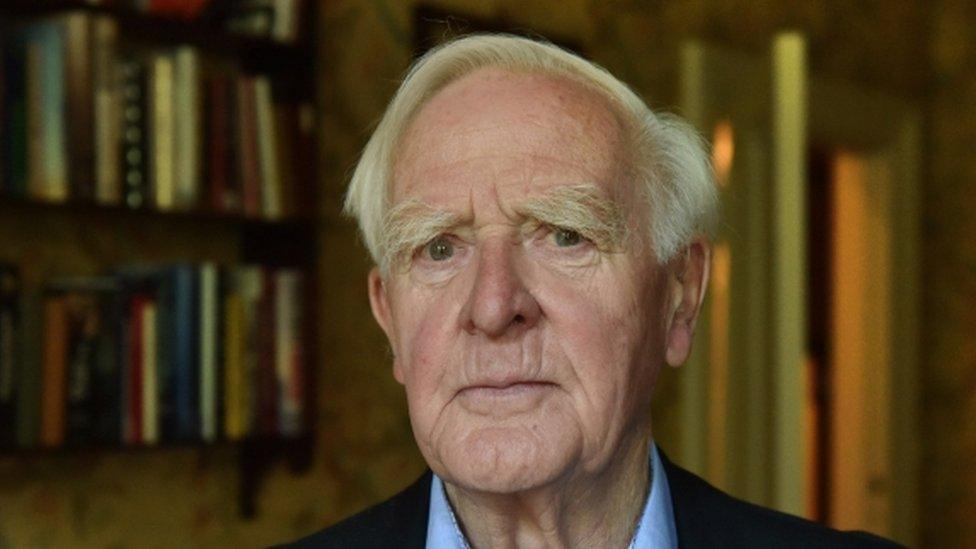

Le Carré closely guarded the truth about his time working for British intelligence

The tweet from the current chief of MI6, external paying tribute to his "evocative and brilliant" novels would have raised a wry smile from John le Carré. The writer's relationship with his former colleagues was always deeply complicated - as has been their attitude towards him.

Le Carré's career was shaped by his time in the secret world and, in turn, his own fiction shaped the way much of the world saw British intelligence, including the way even spies talked about themselves.

Writers often draw on real life experience but because le Carré's experience was inside a world that was secret - and much more secret in his time than today - it is particularly hard to know where fact ends and fiction begins, creating a mystery whose value he understood.

The author's time working at MI5 and MI6 may have been the wellspring of his fiction but he chose to closely guard the truth.

"I have such conflicting memories of my former service - actually of both services - and such conflicting emotions, that I am perpetually at a loss to know what I really think," he once told me, before adding. "It's a matter of pride to me that nobody who knows the reality has so far accused me of revealing it."

The defining aspect of the time which David Cornwell (le Carré's real name) spent inside British intelligence was that they were bleak years.

Complex and morally ambiguous

A series of traitors were, one by one, being unearthed.

"I had barely finished my basic training when George Blake, a longstanding and greatly treasured officer of the service, was exposed as a Russian spy," le Carré later reflected.

The discovery of another bad apple in MI6, Kim Philby, would provide the inspiration for le Carré's most famous work - the Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy trilogy.

His gift was combining the high-stakes Cold War world of treachery with the very human emotions and personal dramas of those who betrayed and were themselves betrayed.

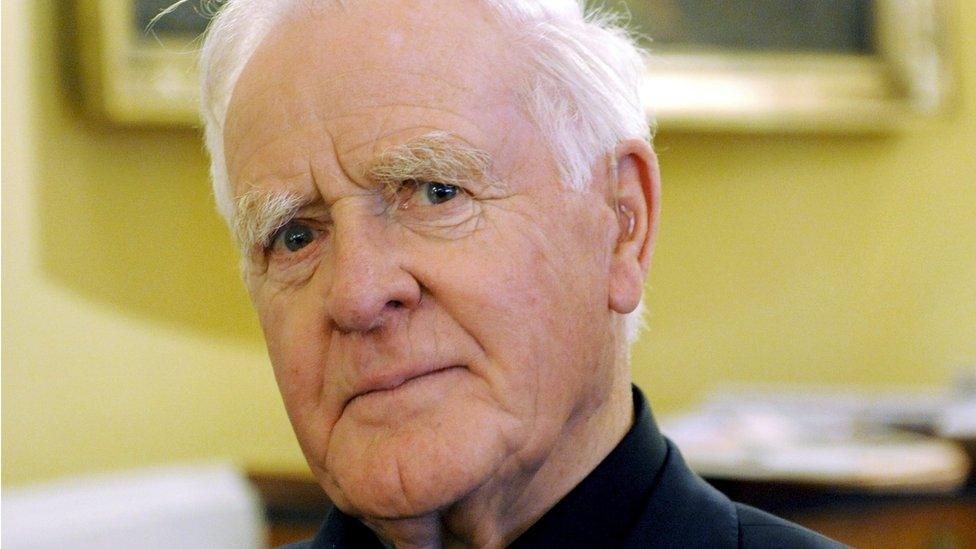

The unmasking of traitors within the intelligence services - such as Kim Philby - inspired Le Carré

Some say the term "mole" to describe an enemy agent burrowing into an intelligence service comes from le Carré and many more of his phrases would become common currency - including among spies themselves.

However, in a1976 interview with Melvyn Bragg, le Carre suggested the term "mole" was not his invention but rather a "genuine KGB term".

The CIA team which works against Moscow has for many years been known as "Russia House" - a name which some believe is drawn from the 1989 novel of the same name.

Some of those who have worked in Russia House have also described to me one particular real-life Russian adversary as their "Karla" - a reference to George Smiley's foe in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and other books.

While Ian Fleming's James Bond was a Technicolor escapist fantasy, le Carré's spies were rooted in a grey, complex and morally ambiguous reality.

But that meant some veterans of MI6 were, it is fair to say, not fans.

"He dares to say that it is a world of cold betrayal. It's not. It's a world of trust. You can't run an agent without trust on both sides," Baroness Daphne Park, who was in MI6 at the same time as le Carré, once told me.

Le Carré was known for morally complex spies such as George Smiley, portrayed by Alec Guinness

Sir Richard Dearlove, a former MI6 chief, criticised le Carré at the Cliveden Literary Festival a few years ago for perpetuating a cynical view (remarks le Carré said were excellently timed as publicity for his next novel).

But just as le Carré had a deeply conflicted relationship with the reality of spies, so spies have had a deeply conflicted relationship with fiction, sometimes disliking the way it shapes perceptions of their world, but also relishing the mythology it provides both at home and around the world.

"There were two feelings I think in the service over the years," Sir Colin McColl, chief of MI6 at the end of the Cold War, told me in 2009.

"There were those who were furious with John le Carré because he depicts everybody as such disagreeable characters and they are always plotting against each other… But I thought it was terrific because… it gave us another couple of generations of being in some way special."

A mythology of spies

In recent years though, the Secret Service has become less secret and more keen to distance itself from fictional portrayal, seeking to root itself in reality instead.

"In my experience, there is fact and there is fiction," Sir John Scarlett, former head of MI6 told the BBC on hearing of the writer's death and paying tribute to him as an exceptional novelist. "They must not become confused."

But fact and fiction have often been confused, especially in the years when secrecy meant there was a vacuum.

Le Carré himself knew that his fiction had fuelled the mythology of spies and, at times, sounded conflicted about that as well.

"The trouble is that the reader, like the general public to which he belongs, and in spite of all the evidence telling him that he shouldn't, wants to believe in his spies," he once wrote.

Related topics

- Published14 December 2020

- Published13 December 2020