Are streaming algorithms really damaging film?

- Published

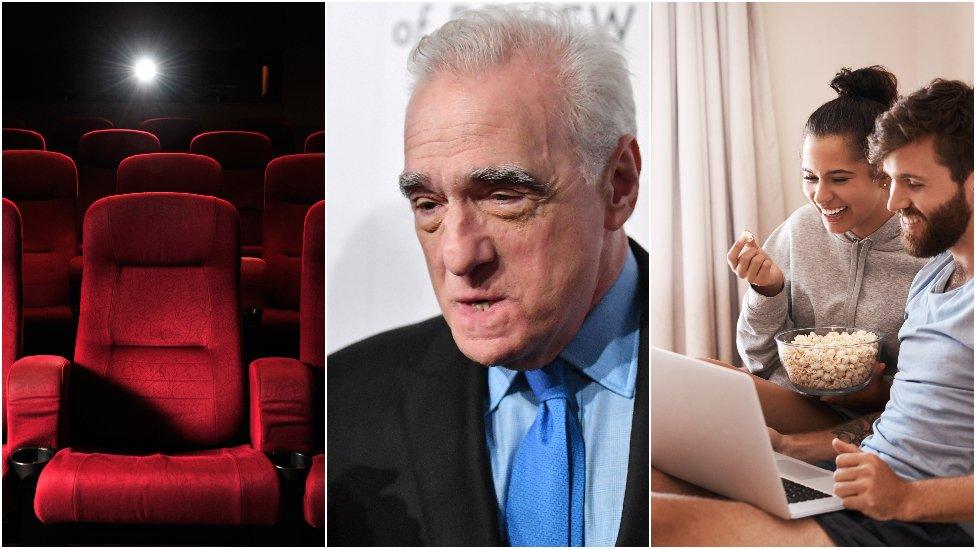

Director Martin Scorsese says the art form of cinema needs to be protected against streaming services

For many stuck inside during lockdown, streaming services have kept the movie-going experience alive - offering a safe alternative while cinemas remain shut.

But film director Martin Scorsese isn't such a fan. In an essay for Harper's magazine, external, he's warned that cinema is being "devalued... demeaned and reduced" by being thrown under the umbrella term "content".

He specifically criticised a lack of curation on streaming platforms, saying algorithms, which provide recommendations based on individual or collective viewing habits, are damaging the art form and "treat the viewer as a consumer and nothing else".

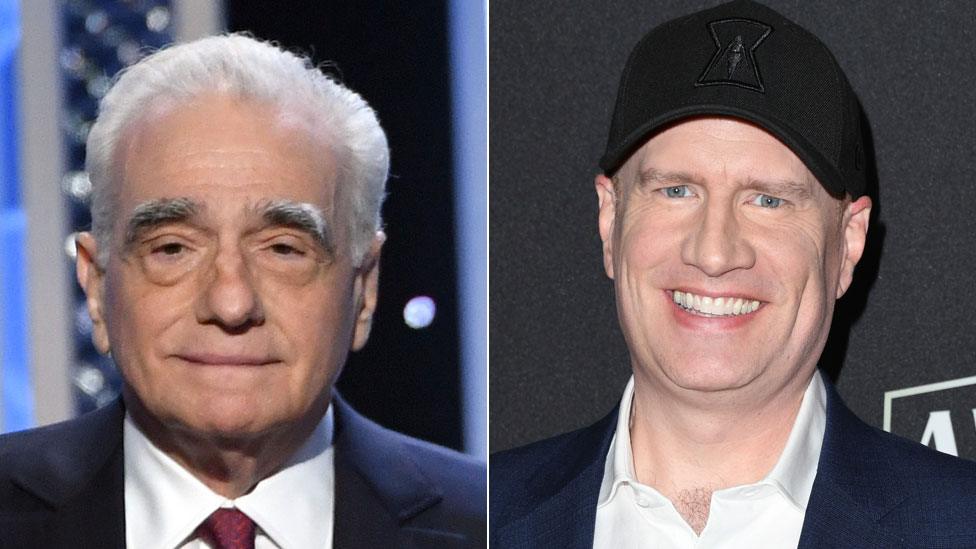

It's not the first time that Scorsese, the Oscar-winner behind classics including Raging Bull and Goodfellas, has spoken out against the state of the industry. In 2019, he bemoaned the multiplex's reliance on superhero movies, comparing Marvel films to theme park rides.

But just how do these algorithms work and are they really as culturally damaging as Scorsese suggests?

'Welcome to the Matrix'

Algorithms work out what you're interested in and then give you more of it - using as many data points as they can get their hands on.

Film has long told a cautionary tale of computers and technology being developed to enhance and serve human interest. From The Terminator to The Matrix, the futuristic blockbuster message has consistently been that machines cannot be trusted.

And yet the entertainment industry increasingly relies on this concept to keep audiences watching.

The Terminator and The Matrix are just two of the films to have given machine-learning a bad name

Streaming-service algorithms use different aspects of your behaviour to inform the way the company will categorise, sort, filter and present different types of content.

This spans formats, from films, TV and music, to different recommendation sources - labels, genres, playlists and other users who may share your tastes.

All of this is sold in the name of personalisation, explains Elinor Carmi, research associate at Liverpool University's communication and media department.

Algorithms 'nudging' people

"To track your behaviour and assemble a profile, these platforms make sure that only one individual is associated with an account," she says.

"Even when you pay for an account that can cater for several people on Netflix, Amazon Prime or Apple TV, it offers each individual a separate entrance which will have all of your preferences, behaviours and patterns.

"Algorithms operate at the back-end of the interface people see when they log on, this has specific ways of indicating and nudging people into what they should choose - from prioritising things at the 'top' of search/display buttons, colours, and even images."

Netflix previously revealed they even personalise thumbnail images for some shows, with the algorithm picking out the most appealing depending on the individual's viewing history.

Stranger Things is one of Netflix's titles given a selection of materials that the algorithm then matches with viewer preferences

"We don't have one product but over 100 million different products with one for each of our members with personalised recommendations and personalised visuals," read a post from their tech blog, external.

The aim of Netflix's personalised recommendation system, just like those of its competitors, has been to "get the right titles in front of each of our members at the right time".

But Scorsese fears machine-learning simplifies the user's experience.

Algorithms, he says, are reducing everything to "subject matter or genre", rendering any kind of curation, and understanding of artistic worth, meaningless. There are exceptions, he says, such as the Criterion Channel and other outlets which are "actually curated".

Content, he says in his essay, is now "a business term for all moving images: a David Lean movie, a cat video, a Super Bowl commercial, a superhero sequel, a series episode".

Netflix's Emily in Paris has been described as soothing "ambient TV"

Is it fair to paint such a disenfranchised picture? Carmi isn't sure. "Unlike what these companies present, humans are always involved," she says.

Instead she sees it as a "battle between the old and new gatekeepers of art and culture".

"At its core, curation has always been conducted behind the scenes", with little clarity as to the rationale behind the choices made to produce and distribute art and culture, she says.

Take the US's Motion Picture Association (MPAA) film rating system. The 2006 documentary, This Film Is Not Yet Rated, explored how film ratings affect the distribution of films, and accusations that big studio films get more lenient ratings than independent companies.

"But it would be a mistake to present the old gatekeepers in romantic colours compared to new technology companies. In both cases, we are talking about powerful institutions that define, control and manage the boundaries of what is art and culture," Carmi says.

'Rise of ambient TV'

So just how is the streaming service infrastructure influencing listening and viewing habits?

The arrival of Netflix's "top 10" list last year caused a stir by revealing some surprising inclusions that gave some indication of the platform's approach.

In a Guardian article asking why choices were "so unhinged", external, Wendy Syfret wrote: "Netflix doesn't make money from acclaimed hits or respected output; it succeeds by coaxing people to spend massive amounts of time on their site."

This meant offering content to accommodate any person, in any mood and "making sure they don't close the tab", so artistic integrity isn't always the priority, as shown by the rise of "ambient TV".

Discussing the trend in a piece for the New Yorker, external, Kyle Chayka cited Emily in Paris as a prime example. Despite attracting some criticism from critics and on social media, it still dominated global Netflix top 10 lists.

The purpose of the show, he wrote, "is to provide sympathetic background for staring at your phone, refreshing your own feeds - on which you'll find Emily in Paris memes, including a whole genre of TikTok remakes."

"We could not get any financing" from Hollywood, says Scorsese about The Irishman

So is Scorsese right to suggest that streaming services reduce content to the "lowest common denominator"?

Journalist and media lecturer Tufayel Ahmed suggests they are an easy target, and the reality is a little more complex.

He says the focus on "pulling in the numbers" can mean some of the best shows don't get the promotion and are therefore cancelled.

"Take a show like The OA on Netflix", he says, "which was critically adored but cancelled after two seasons, the latter of which didn't hit the same audience numbers.

"Some of the best stuff on streaming seems to get little buzz, while tons of marketing and publicity is thrown behind more generic fare that they know people will watch. It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Michaela Coel stars in, wrote and co-directed I May Destroy You

Scorsese himself directly benefited from this by relying on Netflix to fund his 2019 gangster film The Irishman after traditional studios baulked at the cost.

"There's an argument to be made about streaming services investing in publicity and marketing for these projects to create awareness," says Ahmed.

But if responsibility in part lands on the shoulders of streaming services, the choices of the audience themselves cannot be forgotten.

"Algorithms alone can't be blamed for people consuming lowbrow content over series and movies that are deemed worthy, because people have flocked to easy viewing over acclaimed dramas on television, for example, for years.

"Shows like the BBC's Mrs Brown's Boys and ITV's The Masked Singer get huge figures - in comparison, how many people watched I May Destroy You live on BBC One?" asks Ahmed.

But despite this, he does see some reasons to be positive. He says streaming services have been more open in telling diverse stories that reject Hollywood's traditional male white gaze.

Channel 4's It's A Sin, which focuses on the 1980s HIV/Aids epidemic, has drawn record viewing figures to the channel's All4 streaming service

"Streaming has allowed shows like I May Destroy You and It's A Sin, which feature marginalised characters - black and LGBTQ - who wouldn't otherwise lead prime-time shows to be shown to the masses."

Perhaps then, the streaming algorithms really aren't to blame after all, but simply made in our image.

Follow us on Facebook, external, or on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published12 November 2019

- Published5 August 2020

- Published5 February 2021