To make it in music, be prepared for the pitfalls

- Published

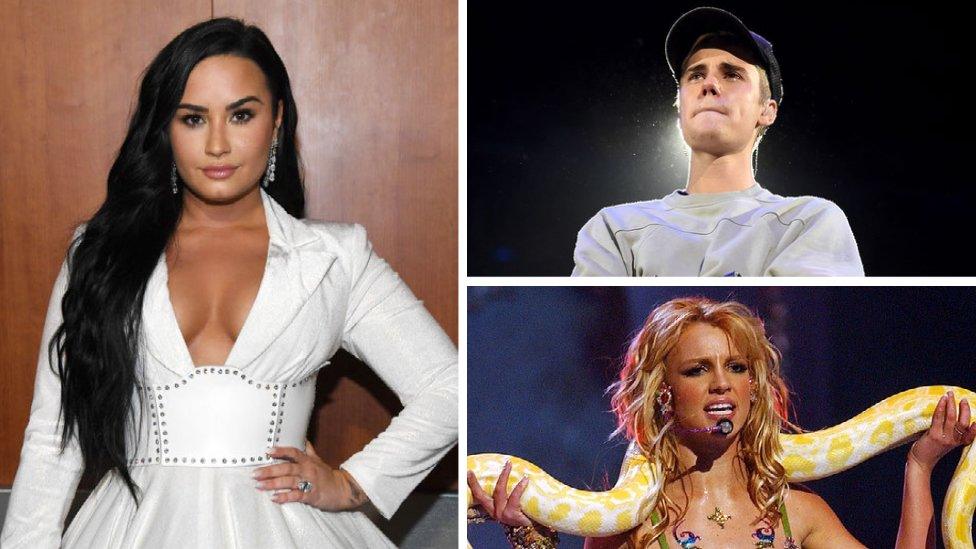

Singers including Demi Lovato, Justin Bieber and Britney Spears have spoken of the toll a career in music has taken on their mental health

"We all just wanna be big rock stars / And live in hilltop houses, driving 15 cars."

The wisdom of Nickelback, there, in the 2005 single Rockstar.

It's a parody of a shallow musician's ambitions - but there can't be many singers who haven't dreamt, at least in passing, of living in that hilltop house.

The reality of stardom is very different. Anyone who has watched Framing Britney or Billie Eilish's new documentary over the last two weeks will be acutely aware that fame often comes with a side helping of mental and physical health problems, not to mention alienation and loneliness.

"I don't think I could think of a single thing that's more isolating than being famous," Lady Gaga once told Variety magazine, external.

Despite that, people still crave a career in music. Some even pursue fame itself. And the vast majority of books on how to enter the music industry share the perspective of Nickelback's wannabe rockstar - "look at what you can get", not "look at what this can do to you".

Strategies for survival

That changed last week, with the publication of Sound Advice - a new handbook for aspiring musicians by journalist Rhian Jones and PhD researcher Lucy Heyman.

Part-funded by labels and live events companies (who had no say in the content), it's a surprisingly frank account of the pitfalls of working in music, with insights on mental health, substance abuse, body image and social media.

"Unfortunately, the large majority of musicians are not going to 'make it'," advises one chapter, which exposes that the average musician in the UK makes just £23,000 a year. "You may well be the next superstar, but do you have a back up plan just in case that doesn't work out?"

The book isn't trying to dissuade musicians from following their dreams. It's more about helping them recognise problems before they arise - and work out the best strategies for survival.

Heyman conceived the idea while studying the health and wellbeing of artists as part of her doctoral research at the Royal College of Music.

"The findings suggested that the musicians [we] interviewed didn't feel supported with the numerous health issues they were facing," she says.

"There were stories of young artists who had been thrust into the limelight in a short space of time, performing stadium gigs with no knowledge of how to warm up their voice or manage their performance anxiety.

"It became apparent that within the industry we really needed more resources to support musicians with their health."

Happy Mondays star Shaun Ryder shared his experiences of stage fright with the authors

Jones, who has written for Billboard, Music Week and The Guardian, remembers the conversation about musicians' mental health becoming more urgent within the industry after the release of the Amy Winehouse documentary in 2015.

"Support for the health of musicians seemed to me like such a no-brainer - these are the people whose creative output the entire industry is predicated on, so it baffled me that there wasn't much in the way of help."

So, while Sound Advice has the usual chapters on copyright, finding a manager, or what to look out for in a record deal, it also contains advice on how to deal with criticism, and protecting your hearing.

There are some eye-opening details: Did you know that Kanye West has a stipulation in his contract with publisher EMI that he must not retire or take an extended hiatus, ever? Or that Shaun Ryder, the frontman of larger-than-life indie band Happy Mondays, often "shrivels up" with stage fright?

"I found [that] really surprising," says Heyman. "Shaun seems like such a confident, outgoing person, so very few people would have known how hard he found performing.

"A lot of musicians struggle with performance anxiety and, as it's an invisible condition, they often presume that others find performing easier than they do.

"Shaun's story really shows that anyone can be affected, no matter how confident they seem, so seek help if you're struggling as there is so much support available and it is more common than you might think."

'I was abandoned'

"I wish I'd had a book like this available to me," says Lauren Aquilina, a pop singer-songwriter who was signed to Island Records in her teens, only to find herself cut adrift when her first album failed to meet sales expectations.

She can still recall the day her album came out. On what was supposed to be the best day of her career, she woke up "alone in my flat" with nothing on her schedule.

"It was already obvious that the album wasn't going to do well, so all the money had been pulled for any kind of promotion.

"I was just like, ''Oh my God, this is the worst I've ever felt. This is something I've been looking forward to forever - and I just feel bad about myself. I don't feel like I'm good enough. I feel like I messed up.'

"I just exploded so hard that I had to quit music for a bit, which is really sad."

Lauren Aquilina says she's found a new equilibrium in her recording career

After a period in the wilderness, Aquilina found a new manager who gave her the confidence to start making music again. She's since written for the likes of Rina Sawayama, Olivia O'Brien and K-pop group CLC, and is currently working on new solo material.

Writing for other artists "actually saved me," she says, "because it allowed me to remember why I started making music in the first place".

"For me, the ultimate feeling is when you've just written a song that you're really really proud of. That's something that could never be matched by playing shows or all of the other cool stuff that comes with being an artist."

Aquilina says her favourite chapter in Sound Advice addresses that very issue. Simply titled "Setting Goals", it encourages musicians to define the parameters of their own success. You don't have to have a number one single and a million-dollar record deal to feel fulfilled, it advises.

Some artists, like Imogen Heap, have a successful and sustainable career in music - releasing albums, writing the music for Harry Potter and the Cursed Child and designing a pair of musical gloves - without being recognised on the street.

"You don't have to be famous to have made it," she says in the book. "For me, success is being able to be free to be who you are."

'Incredibly challenging lifestyle'

Clear-headed guidance like this seems particularly crucial at a time when the pressures on pop musicians have increased exponentially.

"Music fans and critics - or trolls - have more direct access to musicians than ever before and artists are expected to release music relentlessly to keep up with and maintain demand," says Jones.

"More frequent album releases, and less money made from them, typically equals more tours, and being on the road can be an incredibly challenging lifestyle, especially if there aren't adequate breaks between shows and tours."

"It certainly feels like there are a lot more challenges, especially for emerging musicians," says Heyman. "But we also have a lot more support now."

Rhian Jones (left) and Lucy Heyman spoke to dozens of musicians while writing their book

These days, musicians have access to support from the likes of Help Musicians, Girl & Repertoire, BAPAM (the British Association for Performing Arts Medicine), Music Minds Matter and Tonic Music for Mental Health.

The latter has recently established a new programme - Tonic Rider, external - to help touring musicians whose mental health has suffered during the Covid-19 pandemic.

"There's a lot of depression and despair," says Barry Ashworth, founder of dance act Dub Pistols and patron of Tonic Rider.

"A lot of people, suddenly, their whole income has gone and the government was telling them they had to retrain and they weren't viable.

"It was a real storm, and I've literally been phoning people up every single day - and some of them can't even talk to me. They're like, 'I'm in too much of a dark place to to talk to you.'"

Tonic Rider aims to help by hosting virtual peer groups for musicians, hosted by psychotherapist (and Babyshambles member) Adam Ficek, tackling issues from performance anxiety to suicide prevention. When gigs resume later this year, the programme will expand into venues and festivals.

Ashworth says its part of a wider recognition of the toll working in music can have on performers.

"It can become a problem really quickly: The drink, the drugs, the touring, the rejection, the criticism. Every show can affect you - you go from amazing highs to crashing lows. And I think people have become more and more aware and more open to talk about it".

But with all those drawbacks and obstacles, why would anyone want to pursue a career in music at all?

"Because despite its pitfalls, a career in music can also be incredibly fulfilling," says Jones.

"It's common within research to only look at the problems musicians face, but that doesn't give us a balanced picture of what their experiences are overall," adds Heyman.

"Recent studies have looked at this and suggested that, despite the various issues faced, musicians also experience high levels of wellbeing and find what they do meaningful."

Sound Advice is out now.

Follow us on Facebook, external, or on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published6 March 2020

- Published14 December 2020

- Published5 March 2019