Cured: How mental illness was used as a tool against LGBT rights

- Published

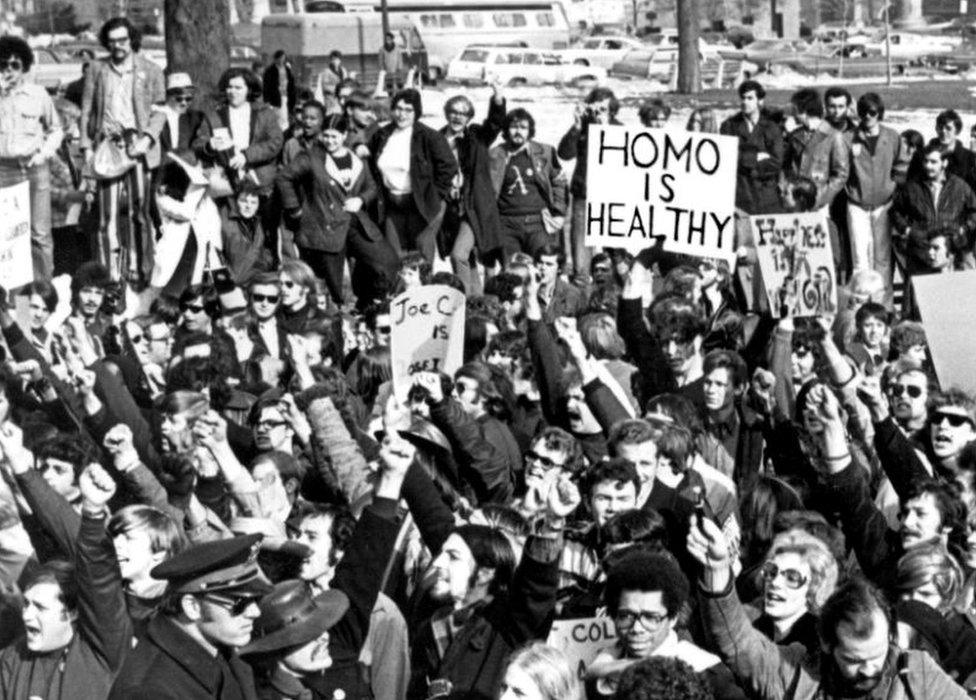

Demonstrators gathered in Albany, New York, in 1971 to demand gay rights

Until 1973 the American Psychiatric Association defined being gay as having a mental illness. A new documentary recalls the struggle to change a definition which for years limited the rights of LGBT people in the US. But the film's makers say the fight for equality was part of a bigger battle which continues today.

The film archive you see in the documentary Cured isn't a total surprise: being gay was illegal in the US when most of the programmes and public service announcements featured were made. The US's path to legalising same-sex relationships would be complex, often with variations between the country's 50 states.

Even so, the prejudices at work in some of the material can be startling.

A police officer was filmed by station WTVJ in South Florida addressing school students in 1966 about the dangers of being near gay people. "They can be anywhere," he tells them. "They can be policemen, they can be schoolteachers. And if we catch you with a homosexual, your parents are going to know about it first..."

The following year an edition of CBS Reports, called The Homosexuals, was probably trying to tackle a controversial topic with an open mind. But reporter Mike Wallace, using the terminology of the time, is repeatedly tripped up by his moralistic commentary.

Kay Lahusen (centre) helped with the founding of the original Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) in 1970

"The average homosexual, if there be such, is promiscuous. He is not interested in or capable of a lasting relationship like that of a heterosexual marriage. The pick-up, the one night stand - these are characteristics of the homosexual relationship."

Film-maker Patrick Sammon describes the programme as "landmark" - but not in a good way.

If you are affected by issues raised in this article, help and support is available via the BBC Action Line.

If you or someone you know needs support with LGBT issues, these organisations may also be able to help.

The documentary he has now made with Bennett Singer tells a story of prejudice within the American Psychiatric Association (APA), a hugely influential part of the US medical establishment. But the first half of the film uses interviews and archive film and TV to illustrate more generally the pressures of growing up gay in 1950s and 60s America.

In 1952 the APA's manual had defined being gay as a "sociopathic personality disturbance". It gave a supposedly scientific rationale to prejudices already widespread in the US and elsewhere. (Gay sex was illegal in England and Wales until 1967; Scotland followed in 1981 and Northern Ireland in 1982.)

Singer says the post-World War Two period appears in retrospect especially homophobic in the US and elsewhere.

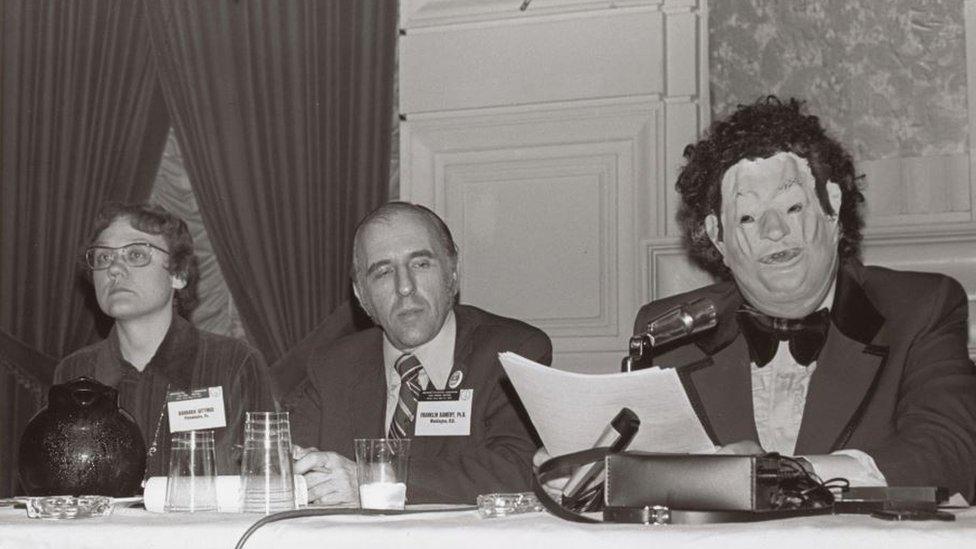

Disguised as "Dr H Anonymous", Dr John Fryer shocked the American Psychiatric Association's 1972 convention by hiding his identity to talk about being a gay psychiatrist

"My sense is that there was a new push toward conformity after the war - a return to normal political life and social life. Embedded in that was this sense of heterosexuality - that men should marry women and that women should have kids and be subservient. This fitted the classic model of what a healthy society was."

Co-director Sammon says part of the reason for making the film was to investigate how far psychiatry itself created or encouraged hostility to LGBT people. "Were psychiatrists the cause or the effect of that prejudice? Certainly the APA classification in 1952 made the atmosphere more hostile. Business and government used it as an excuse to discriminate against and to oppress LGBT people."

Magora Kennedy (right) on the David Susskind show in 1971 arguing against his assertion that being gay was a "mental aberration"

Singer says it's also a matter of how the ruling damaged profoundly the picture LGBT people had of themselves and of whether they were valued in society.

Sammon says one of the most telling bits of archive - showing attitudes tentatively shifting - is an edition of the David Susskind Show from 50 years ago.

"It was a popular nationally-syndicated talk show and the producers invited seven out lesbians to talk about society's attitudes. In 1971 Susskind would have been considered a progressive, liberal and enlightened host. So it's very interesting to hear him espousing the idea that homosexuality was a mental aberration.

"The women really push back and say we're the experts on our lives: we're happy and well-adjusted so why are you espousing these myths? It was quite a fiery confrontation."

There are also striking interviews with those who suffered from the APA assertion that being gay was a mental abnormality, or with those who knew them.

Magora Kennedy, now 82 and described as the "gayest great grandmother in the gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender community", describes being forced to marry a man at 14 for fear of being institutionalised against her will. She remembers the practice as common post-war.

L-R: Activists Ronald Gold (left), Charles Silverstein, Frank Kameny and Barbara Gittings celebrate in 1973 the APA decision to remove homosexuality from its manual of mental illnesses

The late Barbara Gittings, shown as extremely effective in pushing the cause of delisting being gay as an illness, is recalled with affection by her partner of 46 years Kay Lahusen.

Some of the most engaging testimony - delivered with wry humour - comes from Richard Socarides. The gay businessman and former adviser to President Bill Clinton recalls coming out when young to his psychiatrist father Dr Charles Socarides - a leading proponent in the 50s and 60s of the idea that being gay was treatable as a neurotic disorder.

A moment of comic absurdity comes in 1972. Archive shows Dr John Fryer addressing an APA convention in a full face-mask and using a voice-distorting microphone to disguise his identity as he talks about being a gay psychiatrist.

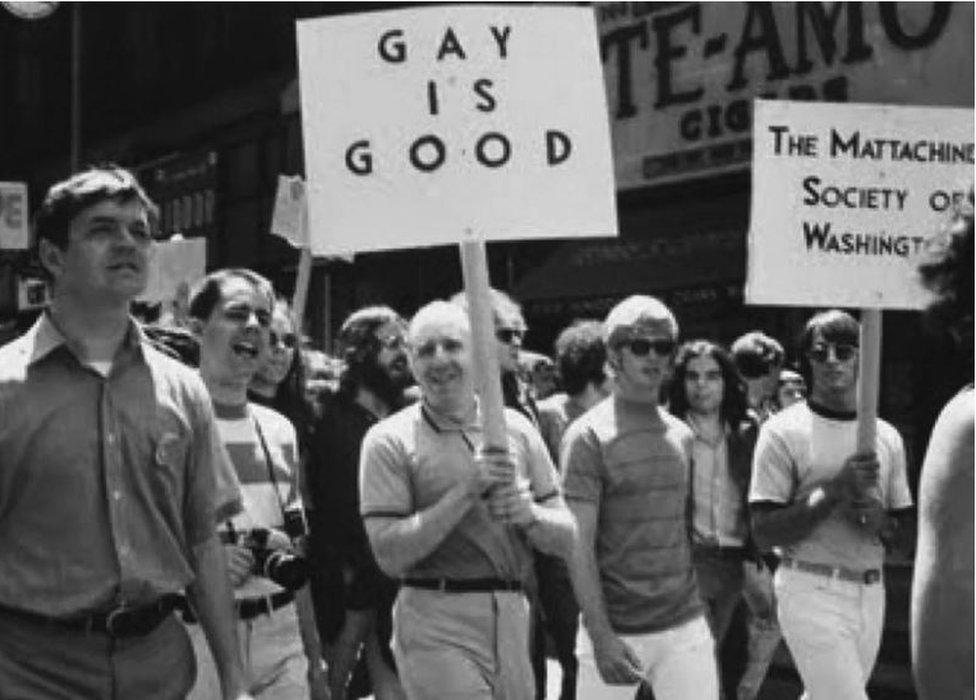

A Liberation Day Parade in 1970 with key LGBT rights activist Frank Kameny (centre), who coined the "Gay Is Good" slogan

It's no great surprise that elements of the film are now in development by 20th Television as a possible multi-part scripted drama.

Sammon says the point the campaigners returned to again and again was the absolute lack of scientific data to support the assertion that being gay was a mental illness. It's clear that a younger generation in psychiatry was becoming uncomfortable with the APA's views.

Eventually - though only over a period of years - the persistence of the campaigners paid off. In 1973 the APA reversed a ruling it had adhered to for more than two decades.

Pride events around the world now celebrate the rights of the LGBT community

So in a way the documentary has a positive ending, with prejudice losing the fight. But Singer sees only a limited reason to celebrate.

"Since the 1960s attitudes have changed dramatically in places such as the USA or Britain. But there are still parts of the world where to be gay is to be in danger."

He says a new threat has now opened up with so-called "conversion therapy, which refers to any form of treatment or psychotherapy which aims to change a person's sexual orientation or gender identity.

"Attempts to 'cure' or 'fix' or 'repair' people based on their sexual orientation or their gender identity are continuing. So it's been heartening for us to connect with activists who are fighting that fight and who see our film as a tool to heighten awareness of past attempts to 'cure' LGBT people.

"Even though this is a story about the past it's a very relevant topic which is still with us today."

Cured is available online until Sunday 28 March as part of the BFI Flare LGBTIQ+ Film Festival.

Related topics

- Published8 March 2021

- Published17 March 2021

- Published11 March 2021