Ezinma: How Beyoncé's violinist is tearing up the classical rulebook

- Published

Growing up, violin prodigy Meredith Ezinma Ramsay hated her middle name.

"I was so embarrassed by it," she says. "I was like, 'Why couldn't you have called me something normal, like Haley?'"

She was given the name by her father, a mathematician from Guyana. Derived from the Igbo language of Nigeria, it means "true beauty" or "good fortune" - but Ramsay didn't appreciate its significance until she read Chinua Achebe's masterpiece Things Fall Apart.

In Achebe's novel, Ezinma is the king's beloved daughter, whose spirit and intellect are so great that he wishes she had been born a boy, and could inherit his kingdom.

After putting down the book, Ramsay says she "felt like I wanted to walk into her shoes - it's such a powerful name".

Now, aged, 30, she's reclaimed the name for herself. When she takes to the stage - whether she's part of Beyoncé's band, or fronting her solo work - Ramsay is Ezinma.

"It felt really bold, like a declaration of who I wanted to be as a woman, and the woman I wanted to become."

Ezinma has become one of the most talked-about classical musicians of her generation.

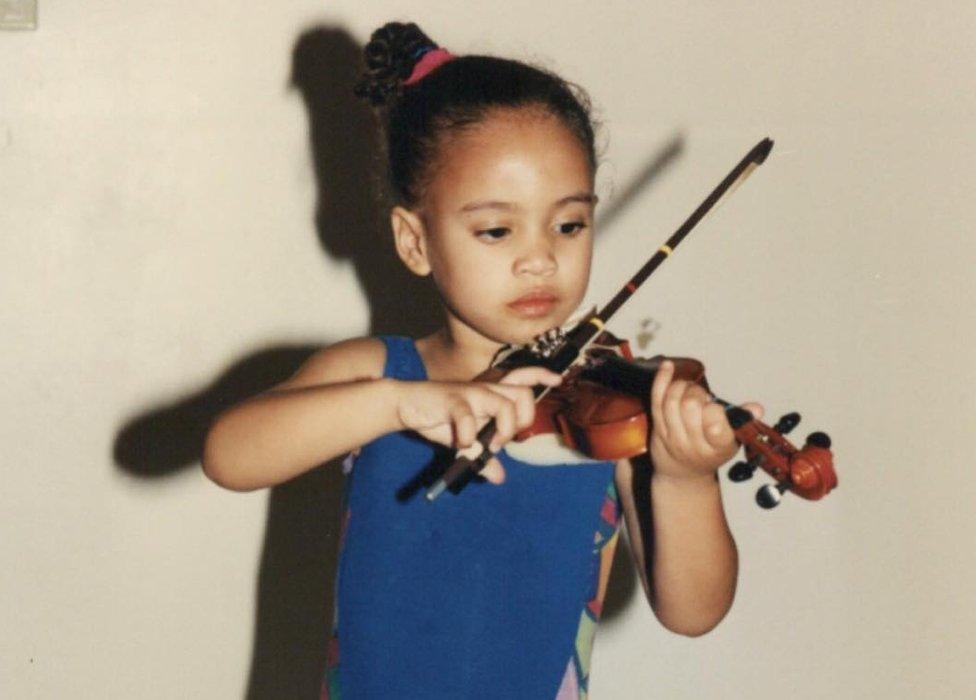

She fell in love with the violin as a toddler, after seeing other kids at her pre-school sweeping a bow over the strings. "For whatever reason, I knew deep inside my little three-year-old body that it was destiny," she says.

Years of gruelling practice followed, taking her from Nebraska to New York's prestigious New School. There, a boyfriend introduced her to music production, and she became "obsessed" with the idea of fusing an orchestral sound with the heavy beats of trap - a subgenre of hip-hop.

Before long, she was hired by Kendrick Lamar, SZA and Mac Miller to add strings to their music. That led to an appearance at Beyoncé's historic Coachella set.

But her solo career really took off when she filmed herself playing along to Future's Mask Off - showing off bold sautillé and flying spicatto techniques, as she added new dimensions to the song's kung-fu aesthetic.

The video went viral and landed Ezinma a deal with Decca Records, who recently released her debut EP, Classical Bae - which puts a new spin on Beethoven's Fifth Symphony and Bach's G Major Prelude, amongst others.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Thankfully, it's no Hooked On Classics - the 80s abomination that saw plastic drum machines tacked onto orchestral performances. Each of Ezinma's pieces deconstructs familiar movements and motifs, then re-contextualises them with stuttering hi-hats and foundation-shaking sub bass.

"It's a very very fine line between cool and corny," the musician admits. "I spent a lot of time making sure that everything feels great and relevant. That's really the concept."

She also hopes it'll open up the classical world to black musicians - who still make up only 1.8% of orchestral musicians, external in the US.

"I feel like, growing up, it would have meant so much for me to hear this type of music, and see somebody like me playing it," she says.

Joining us by video call from LA, Ezinma is full of enthusiastic energy as she discusses her career so far, even showing off the "violin hickey" that's developed on her neck after years of playing.

"It doesn't hurt or anything," she says. "It's something you're proud of. If you see a violinist and they don't have a spot you're like, 'When did you last practise?!'"

Most attempts to fuse classical music and pop are awful... What makes your music different?

I trained classically for most of my life. I studied orchestration and harmonies and motifs and I really respect that music - but I also really respect hip-hop and pop. I was raised with all these different types of music playing in my parents' home and I learned that all music is equal, then I wondered what would happen if I mixed them together.

And I'll admit that my first fusions, which the world will never ever hear, were pretty dorky!

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

What music were you raised with?

So I'm from Nebraska and my mother's an amateur flautist, and my dad is a mathematician - the very opposite of being artsy.

Although music is based on maths...

Yeah, and he loved the patterns and found it really interesting from that perspective. He's West Indian - from Guyana - so we listened to a lot of reggae and soca and funk. And then my mom, she's really into Americana and Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, that type of stuff. So growing up, I actually did fiddling competitions.

Did you win?

That was the best part! I would win, like, 200 bucks and I was just a kid. I really felt a lot of pride in doing those contests.

Was it like the scene in Titanic where Kate Winslet goes below decks and gets swung around by Leonardo DiCaprio?

A little bit like that - but no sinking ships because I was in Nebraska. Totally land-locked!

So was folk music the first music you played on violin?

I started fiddling when I was eight so I already had a foundation of playing the instrument for five years.

But I do think that, stylistically, fiddling affected my playing - the style and the sliding and the use of double-stops. And I just loved the showmanship. That's how you win - by being flashy. I just loved it.

The star first picked up a violin at the age of three

How many hours a day did you practise?

When I was in conservatory, I was definitely playing eight hours a day - between orchestra and quartet and then practising. Now, I don't practise that much, I write and improvise and work with other artists. The hours are roughly the same, it's just divided differently

You studied at the New School in New York - presumably thinking you'd end up in an orchestra or as a soloist. What happened to change your path?

I remember my teacher, Laurie Smukler, saying, "You're just so different from any student I have. I cannot see you in an orchestra. You just need to be your own, like, rock star." It was cool to hear this prestigious violin pedagogue supporting me, giving me permission to explore... After that, I was done.

You ended up playing with Beyoncé at Coachella. What was that like?

It was incredible to watch her put together that show. So inspiring and a lot of work.

You could have had a really lucrative career as a session musician after that, so why did you go solo?

When Beyoncé had her On The Run 2 tour with Jay Z in 2018, I was supposed to go with them and I just decided I didn't want to. I decided I needed to work on my own music, so I turned it down and I moved to this super-crappy apartment in Brooklyn and figured it out.

It was definitely a scary moment because I'd been travelling the world and making money. It was a very big, very scary leap and there was no foreseeable net. But I will say that in times of discomfort, it's usually when I step up and great things happen.

Are you the only person that's ever turned Beyoncé down?

I don't think so! I said yes a lot!

Beyoncé's Coachella performance highlighted the musical heritage of America's historic black colleges

Ezinma has also toured with Clean Bandit, as well as playing with artists like Yo-Yo Ma and Mac Miller

What was it like when your cover of Mask Off went viral?

It changed my life. I made that video on a whim, I was just in my living room and I played the song. The next thing I know, Time magazine were like, '"Can we interview you?"

Of all the covers you've done, what's your favourite?

I really like my version of WAP by Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion. I gave it the most neo-romantic, classical instrumentation; and the juxtaposition was so funny.

It's unusual to see classical music go viral on TikTok. Do you feel like you're reaching new audiences?

It's so powerful, you can reach so many people. But I also think in some ways it can set an unrealistic standard of like, "Oh, anybody can play the violin." And yes, anybody can play the violin, but what you don't know is how hard it is, right? Or how much work it takes.

I do try to open up and talk about the struggles I've had, the rejection and the failure, but the way that the actual algorithm is run... [it seems] like people aren't always interested in seeing that stuff.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The success of those videos led to your first EP - Classical Bae. What do your friends in the classical world make of it?

There's always people who are like, "Why are you doing this?" But for the most part, it's been so well-received. I have young violinists in pre-college at Juilliard transcribing it because they want to learn it; and I've had composers and conductors contacting me and wanting to work together.

Orchestras are still largely populated by white and Asian players. Did you face any resistance when you started out?

The good thing for me was I had the Sphinx Organisation, which is a classical organisation based in Detroit, and they support black and brown players. And then I had the chance to go to Interlochen which is a performing arts boarding school in Michigan. And that was really inspiring because that was the first time I saw somebody who looked like me playing a stringed instrument.

I was 15 [or] 14, and it was so profound, because I think it can be very isolating, when you feel you're the only one.

A documentary about the musician's career to date is currently in the works

Did you have anyone to look up to before that?

There's obviously people like Regina Carter, the amazing jazz violinist, but I grew up before the YouTube boom so it was just hard to really see it. I'm also inspired by [Gustavo] Dudamel, the conductor of LA Philharmonic, just because of the vigour he's brought into the classical space.

He's done a lot to help under-privileged children get involved in music, which is something you're involved with, too, through your Heartstrings foundation.

In the classical world we talk a lot about how to get more diversity. Well, it's about access and opportunity. If we allow more kids the chance to learn, it'll fix itself. But if kids don't have equal chances, then it's hard to have a diverse space because there's so much money required for lessons and all that stuff. So Heartstrings is my little way of helping.

And career-wise, where do you want to go next? Would you like to play a Prom?

Hell, yeah! I think I'm at my best when I'm doing a lot of different things. Right now I'm making a documentary, but I also just can't wait to be out in the world performing and collaborating. This first little EP is one of the many different versions of myself, and I'm really excited to share my voice with the world.

Follow us on Facebook, external, or on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.