COP26: The sculpture created from 1765 Antarctic air

- Published

Wayne Binitie displays his sculpture

Antarctic snowfall two-and-half centuries old forms the basis of a new artwork by Wayne Binitie, titled 1765 - Antarctic Air. It forms the centrepiece to the Polar Zero exhibition in Glasgow throughout the UN climate summit COP26. Binitie says he wants his piece to provide an artistic marker of how much the earth's atmosphere has altered since the crucial date of 1765.

The slightly battered old statue of the inventor James Watt on Glasgow Green stands a couple of miles from the city's modern Science Centre. There's an obvious connection: Watt (who died in 1819) has long been acclaimed as one of the great figures of Scottish science and engineering.

But thanks to Binitie, a Royal College of Art PhD candidate, there's currently a more specific link as well.

In 1765, crossing the parkland where the statue now is, Watt successfully thought through how steam engines - increasingly vital to industry - could be redesigned to become hugely more efficient.

The year 1765 is regarded by some as the start of the Industrial Revolution.

But Binitie says it's also when humans started to do serious damage to the atmosphere which sustains us all. In an unusual artistic collaboration with the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) he's built the significance of that year into the small but striking installation 1765 - Antarctic Air at the heart of the Polar Zero exhibition.

"We wanted to offer some proximity to what's quite a remote conversation now taking place about global warming," he says. "Because of COP26 the Glasgow Science Centre was the obvious place to do it. We're offering a sense of touch and what it means to be in touch with ice and air.

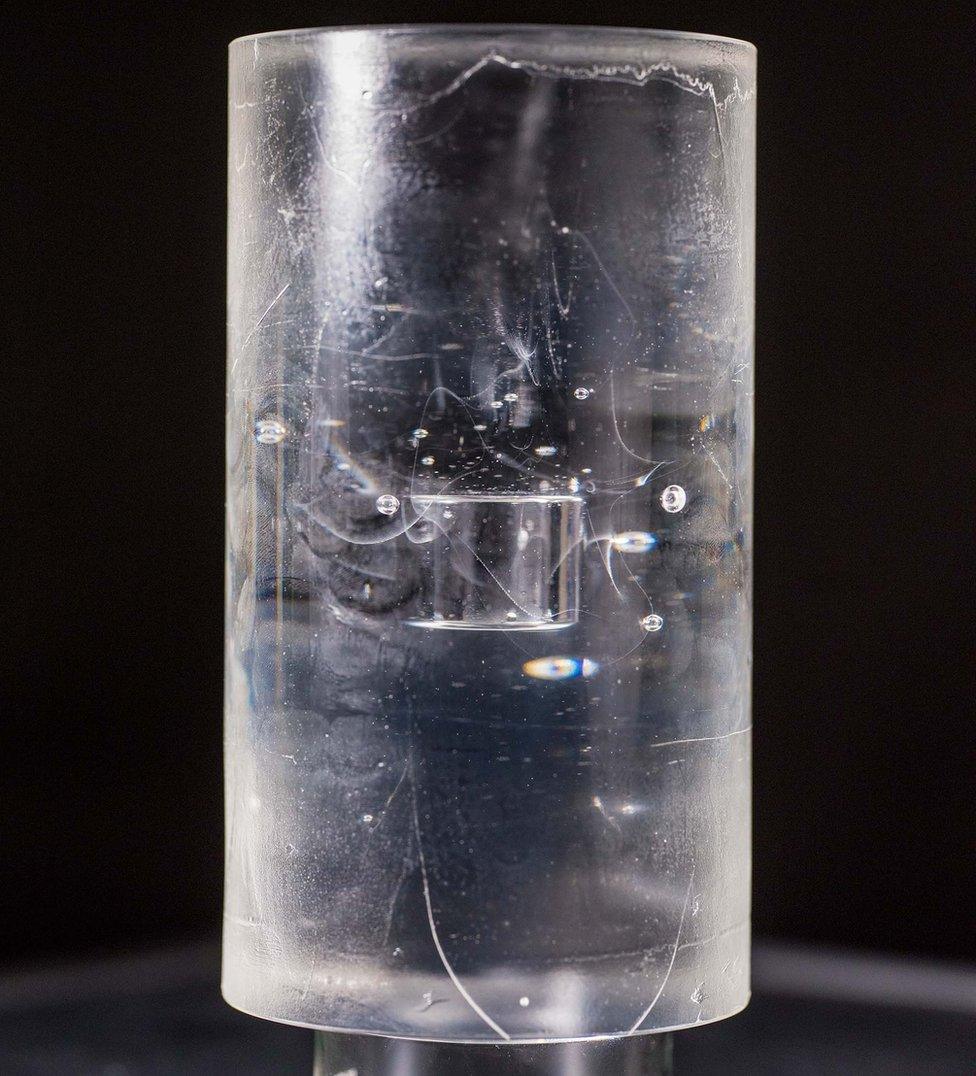

"As you enter the oval-shaped room there's a cylindrical glass sculpture on one side, housed in a floor-to-ceiling black steel frame. The cylinder contains a visible area of liquid silicone and above that is air, carefully extracted from polar ice dating from 1765.

The ice core mined from deep in the snow of the Antarctic

"On the other side of the room is a second cylinder of Antarctic ice. It's intact but you see it melting all the time: it will be replaced during the run of the exhibition with other ice we have in store."

Visitors can touch and hear and if they're brave even taste the second lot of ice. In addition there is a highly evocative soundtrack in the room, blending music and the sounds of nature.

The man who mined the ice for the British Antarctic Survey is glaciologist Dr Robert Mulvaney. He's been visiting the Antarctic for 25 years, staying for up to 80 weeks in a tent to drill out ice-cores before returning to the British base station.

"The essence of what we're doing as scientists is to record what happened to the ice-sheet over a period of many thousands of years: that way we can investigate what happened to the climate and to the atmosphere.

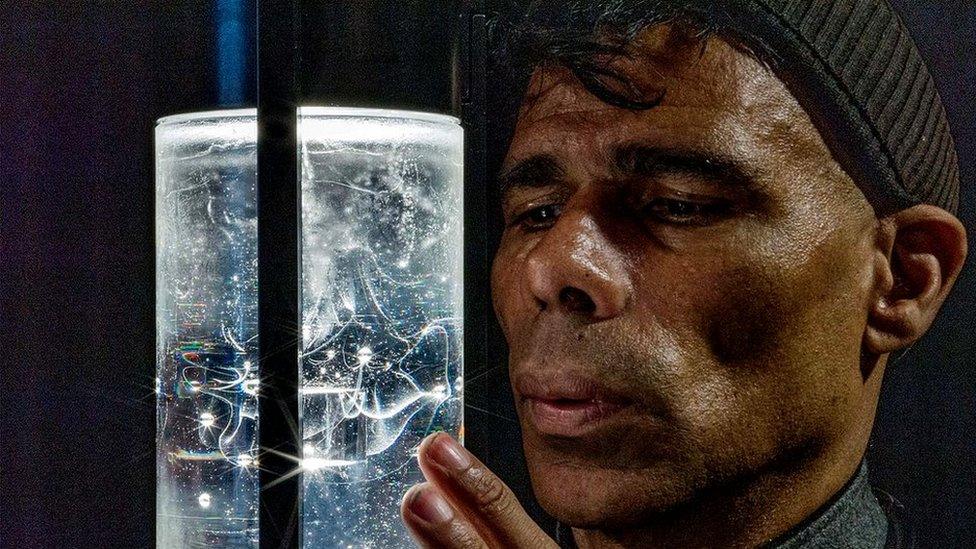

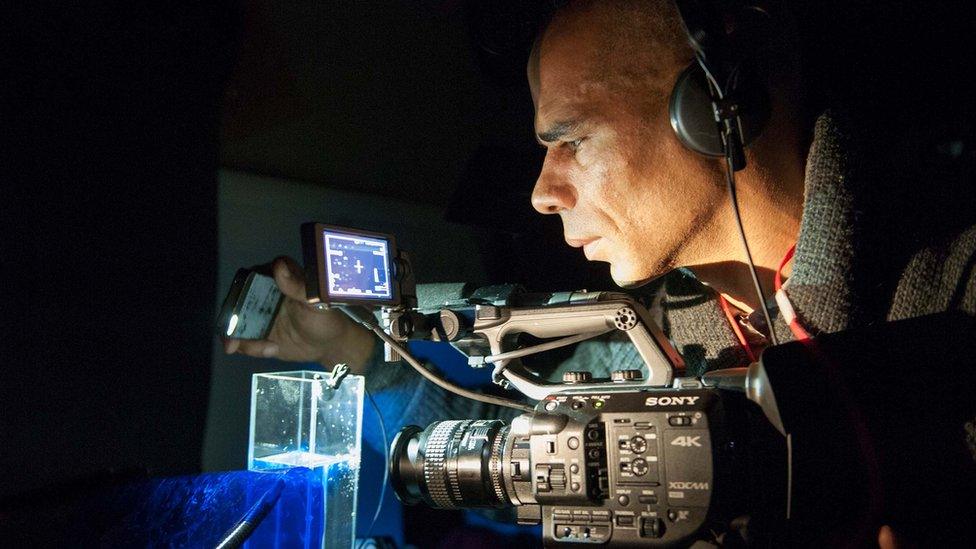

Artist Wayne Binitie documents his work with the Antarctic ice

"For instance next spring I shall be making a trip to Greenland where the ice-sheet can give a record going back around 120,000 years. But in Antarctica we've already been back over 800,000 years and a new project will we hope take us back up to 1.5 million years."

Given those mind-boggling figures the water dripping slowly from Binitie's installation - the ice had already been in storage for 30 years - may seem of minor importance. "We've done all the science on it now and it was surplus to requirements.

"So the British Antarctic Survey was delighted to cooperate on the art project because we want people to understand what's happening to the polar regions. 1765 is usually accepted as the beginning of the period in which human beings changed the atmosphere through the burning of fossil fuels on an industrial scale."

Robert Mulvaney (left), Graham Dodd and Wayne Binitie examine their collaboration on the sculpture

Dr Mulvaney makes uncovering ice from 256 years ago sound like child's play - once you've set up your tents around 1,000km from the home comforts of the Antarctic base station.

"Snow falls in Antarctica year by year - but there's no melting going on. So the snow builds up and compresses all the years of snow beneath. As we drill down we're driving further and further into the past - a bit like counting the rings of a big tree.

"What helps is that every so often we know that a certain volcano blew up in a particular year and we may find evidence of that. So using our drills to find a specific year isn't quite as hard as you would imagine."

Analysis shows that in 1765 carbon dioxide made up 280 parts per million in the air. By the 1960s that had already increased to 315 parts per million. But today the figure is 415 per million - an obvious increase in the rate of change.

The ice supplied for the Binitie artwork came from 110 metres down. The deepest Dr Mulvaney has drilled is around 3,200 metres.

The Antarctic gas being extracted

Binitie was meant to experience all of this courtesy of the BAS but Covid got in the way. It's obvious how much Dr Mulvaney delights in describing the experience of being there. Asked if satellite phones keep the small team safely in touch with the world he says he does his best not to use them: "It brings the troubles of the world onto the site and I need to be focused on the work."

Once the ice core was extracted, the job was to release the flecks of air trapped in the Antarctic in 1765. Binitie's concept is to establish this as a starting line: the purest possible air trapped in ice just before the modern world started to pollute it. The international engineering company Arup helped out with some of the practicalities.

Graham Dodd of Arup says encasing 256 year-old air within glass was a challenge. "After a lot of thought we decided the right technique was to make a casing with a void inside which we then filled with fluid. We had to find a way so Robert could then inject into that space the air extracted from the ice that the BAS had given us.

Antarctic air up close

"The other artistic challenge was to find a way to display the other column, which is simply ice. As an artist, Wayne needed visitors to see and hear the ice dripping away very slowly as that makes the point about global warming. Arup's engineering job was to ensure it doesn't disappear too quickly."

Binitie thinks the global warming conversation can sometimes feel too generic, with issues almost too big to comprehend. "So I hope our installation in Glasgow will persuade people that the polar regions are a sufficiently precious thing to care about. Some perspectives are political or theoretical or economic but we're trying to supply a poetic perspective too.

Binitie hopes some of the VIPs attending COP26 nearby will come to see his installation. "We'd like 1765 - Antarctic Ice to surprise them. I want to do something to encourage a collective conversation: if we move forward collectively we know we can achieve a lot."

Polar Zero is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, part of UK Research and Innovation., external

Related topics

- Published15 November 2021