Len Goodman obituary: From the East End to Strictly Come Dancing studio

- Published

In April 2004, the BBC took a huge gamble.

Desperate to find a new show with mass appeal, it had come up with a seemingly bizarre solution.

Ballroom dancing was deeply unfashionable. The quickstep and jive hailed from an era of Brylcreem and Butlin's holidays. Now, the corporation was attempting to make the nostalgic preserve of a few elderly enthusiasts the centrepiece of its Saturday nights.

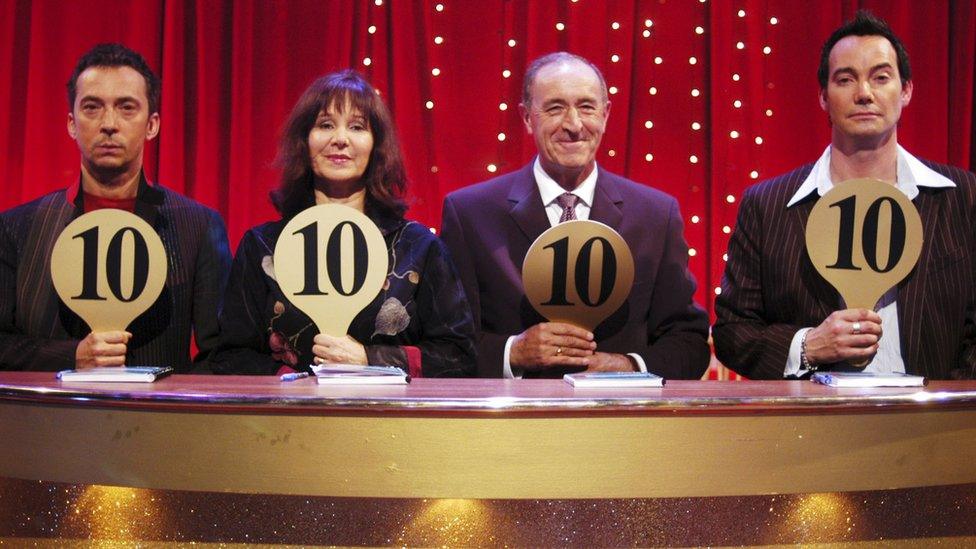

Len Goodman was a last-minute replacement for a judge that dropped out

Just days before the first show, the producers hit a crisis.

Four judges had been offered contracts: Craig Revel Horwood, Arlene Phillips, Bruno Tonioli, and a well-known figure from the world of dance. At the very last moment, the fourth judge dropped out.

The BBC was at a loss. Dozens of former world champions - giants of their profession - had already been interviewed, but none had been right. The show's professional dancers were asked if any luminaries had been missed.

Erin Boag, the former New Zealand champion, tentatively offered a suggestion. "Have you tried Len Goodman?" she asked.

"He's just a dance teacher from Dartford, but he's a bit of a character."

The dance teacher from Dartford was said to be "a bit of a character"

East End barrow boy

Leonard Gordon Goodman was born in Farnborough, Kent, on 25 April 1944.

He grew up in London's East End in an over-crowded two-up, two-down terrace. There was "lots of love and laughter, but very little money", he recalled.

It was a tough neighbourhood. Two of his uncles had been active members of Sir Oswald Mosley's British Union of Fascists before World War Two. When hostilities broke out, angry crowds attacked the family home in Howard Street. Serious injuries were only prevented when the sound of an air raid siren dispersed the mob.

The family scraped a living selling vegetables from barrows. Goodman's grandfather Albert pawned his gold watch every Monday morning to buy the week's supply.

Len Goodman grew up in the post-war East End of London

Len watched the old man attract customers with a smooth patter dotted with earthy phrases. He later used many of his grandad's lines on Strictly Come Dancing.

Albert Goodman was good at his job. The barrow became two shops in Bethnal Green - with enough money left over to buy Len's parents a greengrocer business in Kent.

Soon after they moved, the marriage fell apart. Goodman's father moved away, and his mother buried the shame of divorce by throwing herself into her job.

'You'll be a failure'

At school, young Len enjoyed football and cricket - but was no academic. "It's obvious you're never going to amount to anything, Goodman," his headmaster declared. "You're a failure in class. You'll be a failure in life."

To help his mother, he pushed a barrow of vegetables around town every evening - just as his grandfather had. This, Goodman believed, was a more valuable education than school had ever provided - as it taught him how to speak to people and engage them.

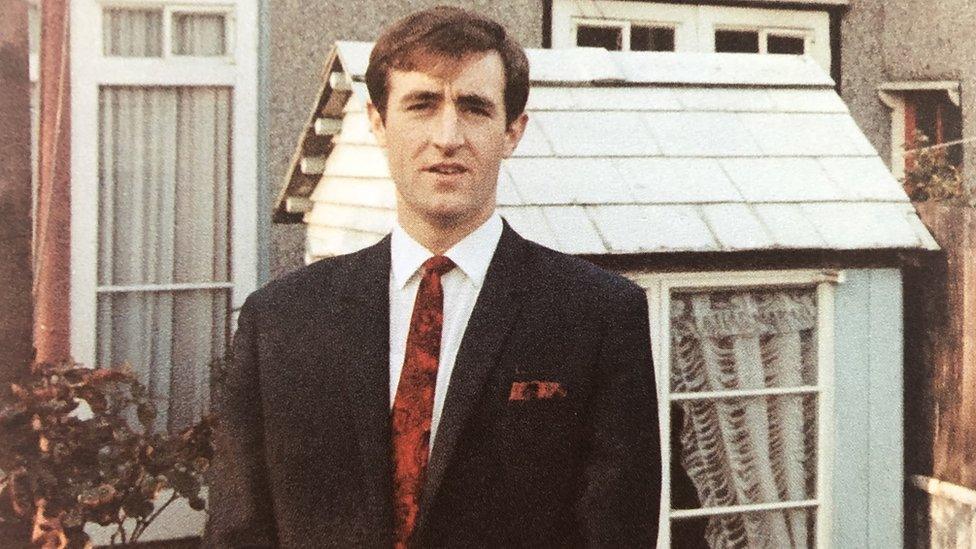

Len Goodman in his sharp 1960s Mod suit

At the age of 14, he went to his first dance class. He had little love for the foxtrot, but a keen interest in girls. The most thrilling moment of the night, he later wrote, was the 'excuse me' dance - during which you had to kiss your partner goodbye.

A year later, Goodman left school "with no sense of loss on either side". He began an apprenticeship in an engineering factory but, by his own admission, was dreadful at it.

He took a welding course and found work in the Harland and Wolff Royal docks in Woolwich. It wasn't a job he liked, but it brought in enough money to enjoy himself at weekends.

Goodman became a sharp-dressed Mod, hanging out on his Vespa in Brighton on Saturday afternoons, trying to avoid fisticuffs with gangs of rival Rockers.

Like many of his generation, he worshipped rock 'n' roll and regarded ballroom dancing as something 'old fogeys' did. Then, he broke his metatarsal playing football on Hackney Marshes, and was advised to find an activity to help build its strength again.

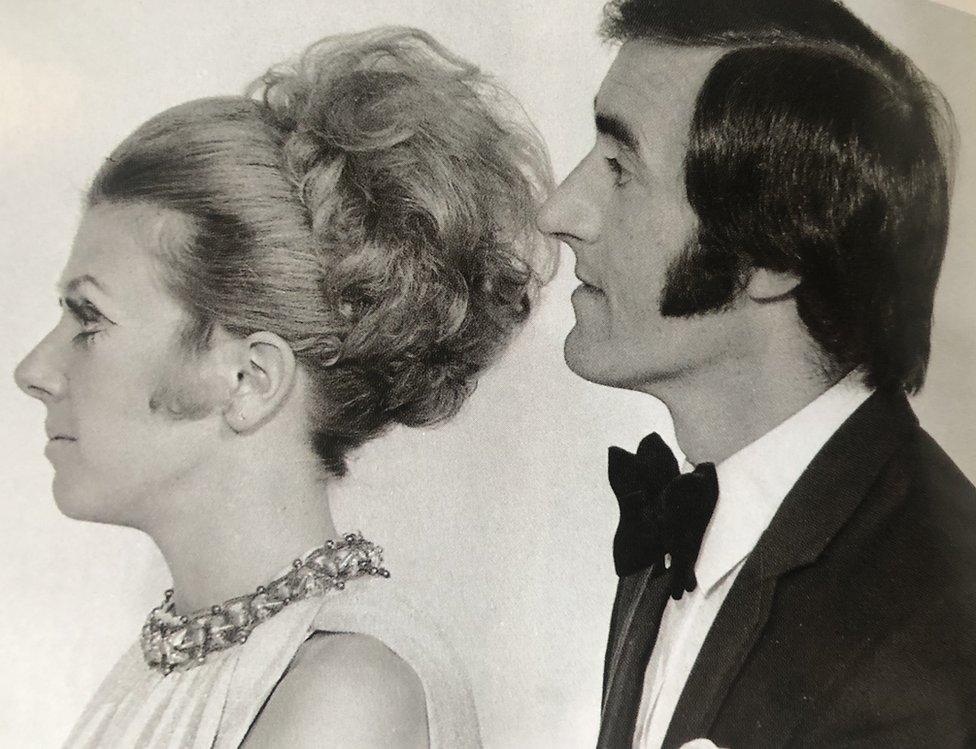

With his dance partner and first wife, Cherry

Falling in love

Joy Tolhurst was a former world champion. At her first dance lesson, Goodman was hampered by wearing a winklepicker on one foot and a carpet slipper on the other. Slowly, he fell in love with the both the waltz and Mrs Tolhurst's daughter.

He and Cherry Tolhurst became partners on and off the floor. Their first competition was a Pontin's sponsored event at the Royal Albert Hall. Goodman practiced in his front room, with a lamp placed behind him - so he could see his hip action in the shadows.

Len and Cherry toured the country teaching people how to dance

As the couple sashayed onto the hallowed stage, Goodman heard great bellows from the audience. Fifty-three fellow dock workers had hired a coach to come and support him, and were well lubricated up.

When Joy's husband died suddenly, she asked 22-year-old Len to help her teach. Learning from an ex-welder was a shock to students used to a poised former professional.

Cha-cha-cha

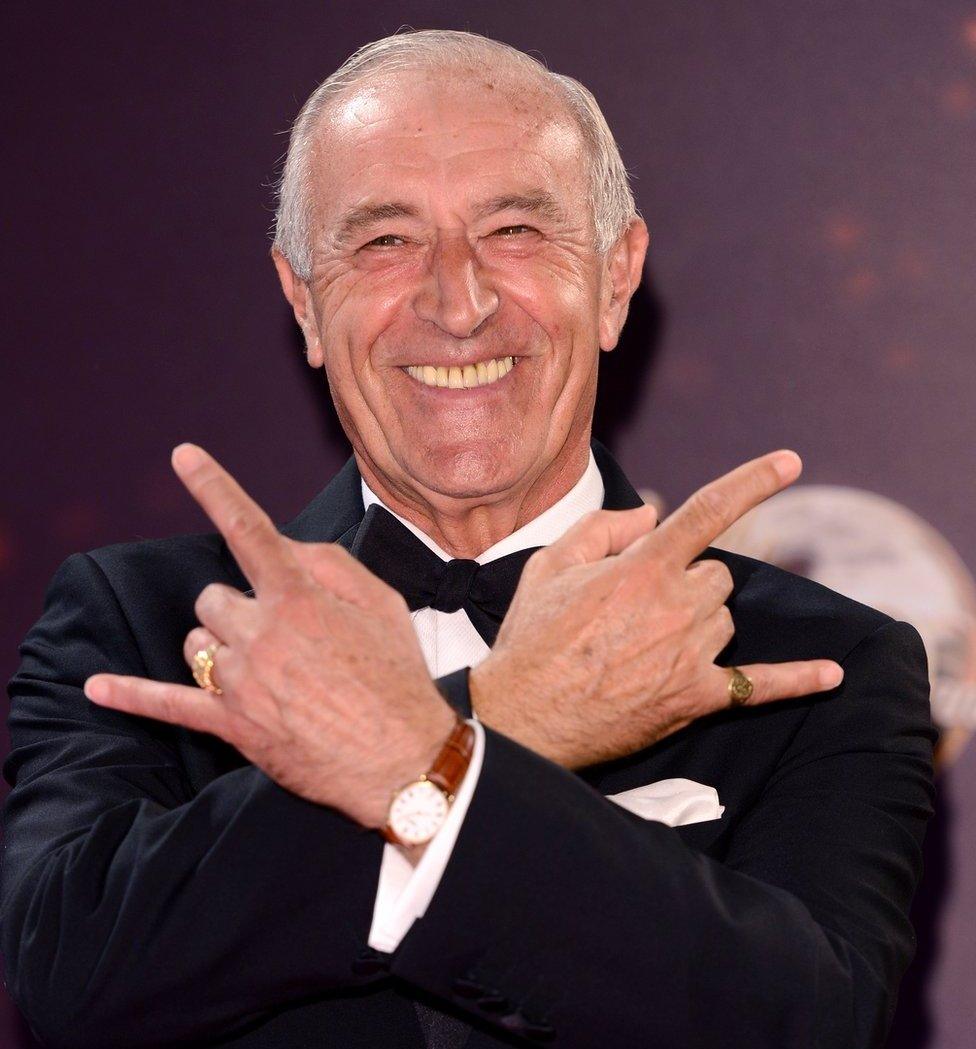

A "10 from Len" was reserved for the very best dancers

By 1973, Goodman and Cherry were driving thousands of miles a year, demonstrating the cha-cha-cha and rumba to amateur classes the length and breadth of the country.

They married and opened their own dance school in Dartford. The couple won a rising star competition in Blackpool - but decided not to compete professionally again.

"I got fed up with the politics of the business," explained Goodman. "The fact that you had to placate and schmooze people that you didn't really like, because you did not upset them, as they were judges."

The decision took a toll on his marriage which, he admitted, had become more of a dance partnership than a relationship.

When the dancing stopped, everything collapsed. Cherry left him for a multi-millionaire Frenchman, leaving Len in an empty house and with only half a business.

His heartstrings were healed when he met Lesley, a former wife of the manager of Black Sabbath. A year later, the couple had a son.

Night Fever

What saved his business was the film Saturday Night Fever.

Goodman put up posters: "You've heard the music, now learn the dances." There were queues halfway down Dartford High Street and, when Grease came out, "the seam of gold turned into a whole goldmine".

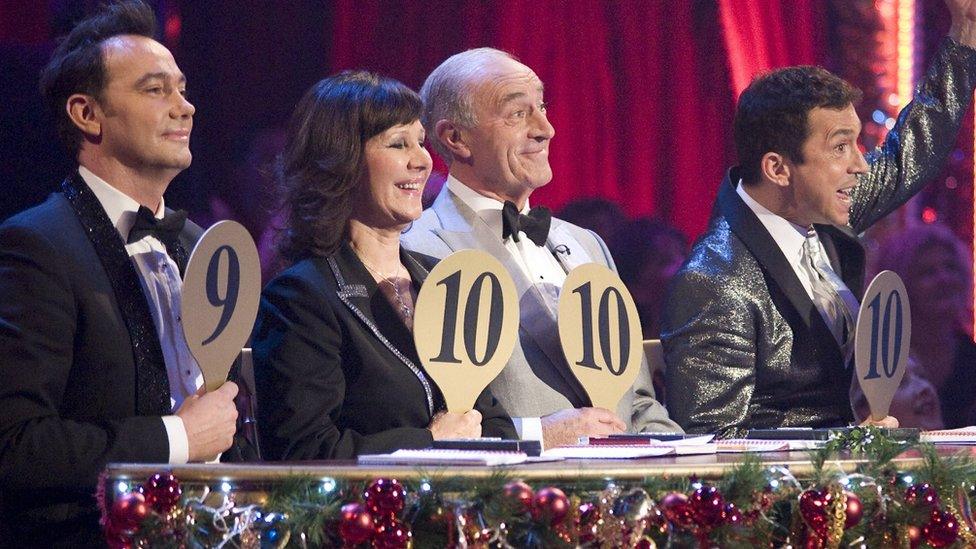

Goodman with fellow Strictly judges Bruno Tonioli, Craig Revel Horwood and Darcey Bussell

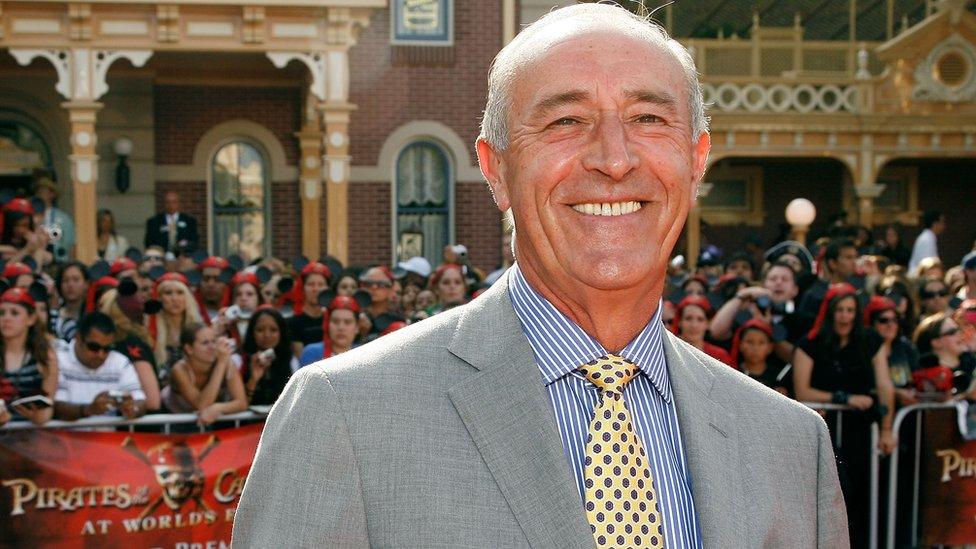

By the time the BBC rang to suggest he audition for Strictly Come Dancing, Goodman was about to turn 60. He was settled with his new partner Sue, and their dance school was performing well.

In truth, he wasn't looking for new challenges. He was hoping to wind down his business and play a little golf. But his competitive instincts kicked in, so Goodman caught the bus to Strictly's studios, wearing his best tweed suit.

Revel Horwood, Phillips and Tonioli all had backgrounds in theatre, but none knew ballroom. Len was concerned that the show might "take the rise" out of the discipline he loved - which could destroy his reputation.

To take part, he had to break a contract to judge the Blackpool championships - which clashed with the first TV show. It wasn't just the BBC that was taking a gigantic risk: Goodman knew he would never be asked again.

Goodman with his fellow judges on ABC's Dancing with the Stars, Carrie Ann Inaba and Bruno Tonioli

'All sausage, no sizzle'

He decided the best thing was just to be himself. In the first show, he trotted out one of his grandad's favourite phrases, "all sausage, and no sizzle", and quickly settled in.

The audience loved his pithy observations. "It's a lovely rise and fall, up and down like a bride's nightie," he told one nervous contestant. "You're just like a trifle - fruity at the top but a little bit spongy down below," he informed another.

At heart, he was a teacher and was quick to offer practical advice. But one of the show's first brave celebrities, Jason Wood, discovered Goodman had a sharp tongue. "Wood by name, wood by nature," he said.

With millions watching, the Americans picked up the show. ABC booked Tonioli to appear alongside two US judges on the rebranded Dancing with the Stars - only for history to repeat itself.

Dancing was never work for Len Goodman

One of ABC's picks did not perform well in the pilot programme. With 24 hour's notice, Goodman was put on a plane to Los Angeles.

For more than a decade, he crossed the Atlantic twice a week - appearing as head judge on both shows simultaneously. While in LA, he shared an apartment complex with Tonioli - with Bruno doing the cooking and Len the ironing.

Goodman's natural charm worked so well on camera that he was offered other presenting opportunities. There was even a short-lived BBC game show, Partners in Rhyme.

But, in his 70s, he decided the constant flying back and forth had become too much. He left Strictly Come Dancing - with much emotion - in 2016 to concentrate on the (much better paid) ABC version.

Then in 2022, he left the US show to "spend more time with my grandchildren and family" in the UK.

International fame came late to Len Goodman. When it did, he had spent long enough in obscurity for it not to affect him.

He may never have been a world-class dancer himself, but his easy-going charm made him a natural TV performer.

For the ex-welder, none of it was work. "Work," he insisted, "was something you didn't like doing."

"You've heard the expression I could've danced for joy?" he once wrote. "Well, I have and still do."

Related topics

- Published24 April 2023

- Published24 April 2023