Joy Division: Photographer Kevin Cummins on capturing the post-punk icons

- Published

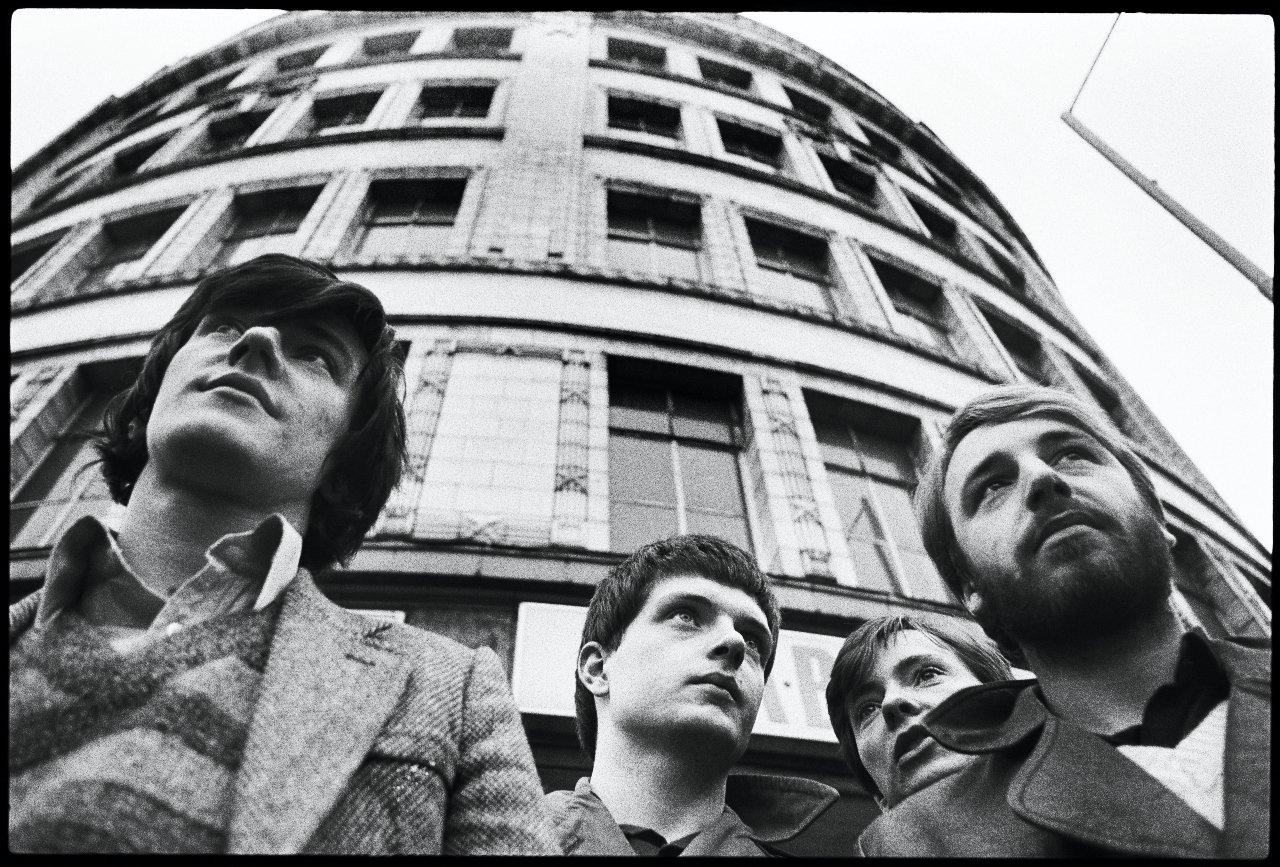

Left-right: Stephen Morris, Ian Curtis, Bernard Sumner and Peter Hook reflected the heart and soul of Manchester in the late 1970s

In 2002, music photographer Kevin Cummins was approached by a young woman after giving a talk in Manchester.

He didn't immediately recognise her, but it was Natalie Curtis - the daughter of Joy Division's late lead singer Ian.

She wanted to ask a simple question - did Cummins have any pictures of her dad smiling?

Cummins famously photographed Joy Division in the late 1970s, and his atmospheric pictures have come to define the image of not just the band, but also of the post-punk music scene in industrial Manchester.

When the singer took his own life at the age of 23 in 1980, the famous black-and-white stills took on an even greater resonance. The images are now being published in Joy Division: Juvenes, an updated collection of his work with the band.

But despite Natalie's request for a memento of her dad's happier side, Cummins had purposefully given the images a sombre mood. He explains he "very rarely" took pictures that captured the band when they were all smiles.

"That wasn't the agenda. I wanted to photograph the band looking like serious young men," he says. "If they smiled on a picture, I generally didn't take it because I couldn't afford to waste any film.

"I wanted... to create an image for them that so that people would look at them and think they were perhaps a lot more cerebral than they were and to make them slightly unattainable."

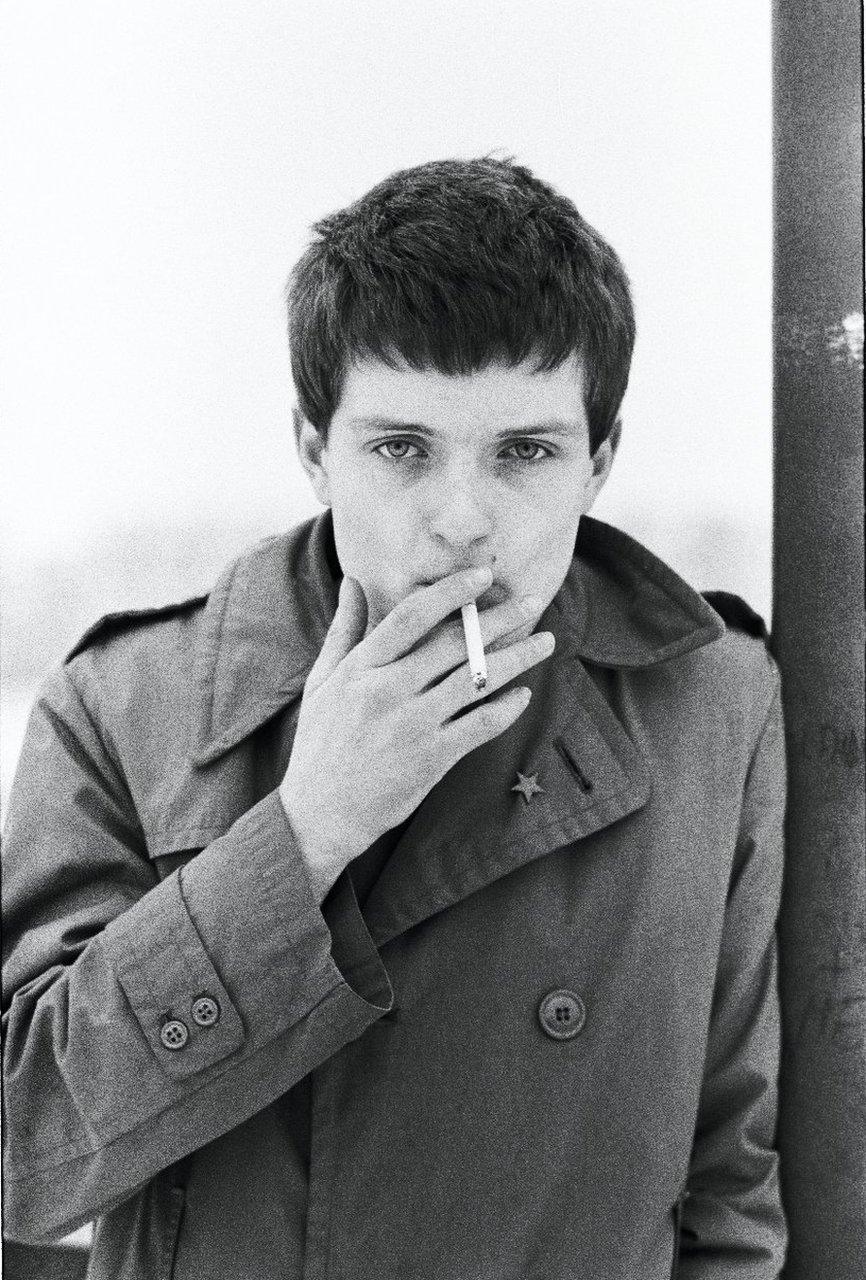

Curtis with Sumner, who would go on to front New Order with the remaining members of Joy Division

This month marks the first time the book has been released for a mass audience, after a limited run of just 226 copies in 2007.

While the images hold importance for the group's fans, they are of particular personal significance for Natalie Curtis, who grew up knowing her father's power as a frontman partly through the work of Cummins and other photographers.

"Even as a small child I was aware of the band and knew that my father was the singer, but seeing the black-and-white prints spread out across the carpet brought tangibility," she writes in thoughts reprinted in the book.

As Joy Division "become fiction", in her words, including as in 2002's 24 Hour Party People and 2007's biographical film Control, Natalie explains that she has come to "enjoy the solitude of the photographs".

"The images contain an unexpected tenderness, the band captured on their own terms by someone who understood their world."

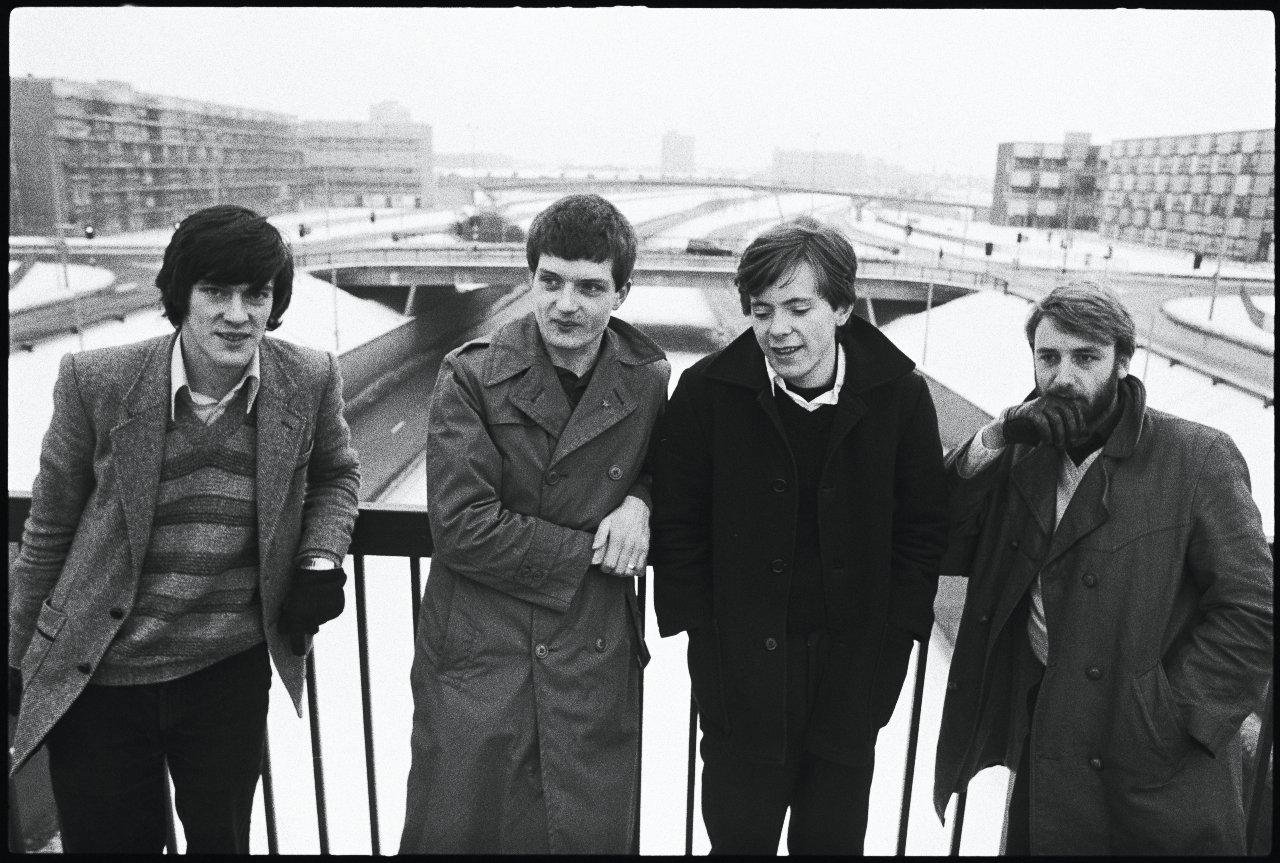

The Princess Parkway shoot on Epping Walk bridge in Hulme includes flashes of the band in lighter, candid moments

Few photographers could claim as close a relationship with the band as Cummins. His images of the band reflected their sound and embodied the steely mood of the time - cold, yet determinedly resilient.

They were modern rock "viewed through night-vision goggles - grainy and murky", wrote Bob Stanley in his book Yeah Yeah Yeah: The Story of Modern Pop., external

This is reflected in perhaps Cummins' most famous shots of Joy Division, taken on the icy Epping Walk bridge over Princess Parkway in Hulme, Manchester, in winter 1979.

"I had to photograph them in black and white because the music press only published in black and white, nobody published in colour," Cummins explains. "Consequently, everything from that period is in black and white. What's happened over the years is, it defines the way you think of the band.

"In a way, we were lucky," he continues. "The cold and the snow helped an awful lot because half the session I did indoors, but half we did in the snow that kind of gave a more graphic, stark quality than we would have had if it had just been a typical drizzly Manchester grey day."

Cummins feels the snow gave his famous Epping Walk bridge shot a "graphic, stark quality"

Although Cummins had a style in mind, the power of the images means they have taken on a life of their own in pop culture. "I don't define what becomes an iconic image," he says. "The public really define that, because it then becomes the picture that people want, share, and feel."

Referring to the photo from that snow-covered overpass, he continues: "Iconic is an easy word to use, but it is a defining image of that band. And it's the picture that most people think of when they think of Joy Division."

The book also contains interviews with the living members of the group - Bernard Sumner, Peter Hook and Stephen Morris - who discuss their music before Joy Division morphed into New Order following Curtis's death.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

His haunting shots with Cummins became synonymous with the band's image, making him a literal poster boy for the raw emotional vulnerability and restlessness of the band's sound.

"He was a good person to photograph because he did what I asked him to do," the photographer recalls of the frontman.

"He understood the process and he was easy to work with. Nobody is the singer of a band if they're shy and reluctant. Singers have an ego, bands all have egos, or else they wouldn't get on stage.

"I want people to be themselves and I want to draw something out of them. That may be something they don't always see in themselves."

Curtis's arresting stare in this 1979 portrait has become an "emblem" of his legacy with the band, says Cummins

A series of solo portraits of the singer, taken from the snowy Parkway shoot, show him holding an intense gaze, cigarette in hand, against Manchester's worn backdrop.

"Ian in that photograph has a really piercing stare, because he's looking at me, he's not stopping his gaze at the front of the lens."

Forty years later, Cummins' work has become something of a time capsule. "I've always photographed for the moment and wanted to capture something of that moment, which is why I like using urban backgrounds and urban landscapes. Because it gives a sense of time," he says.

"Then over the years, when retrospectives happen, and when anniversaries come into play, it really locates them in that moment is quite important historically. So as well as shooting for the moment, you may be shooting so the history remembers them a certain way."

Cummins returned to shoot Epping Walk bridge in 2010

The location and surrounding culture is key to Cummins' work - almost as important to the photo as the band themselves. That's especially the case with the snowy bridge shot, which would later adorn the cover of the band's Best Of compilation.

"What I was trying to do with that shot was to do maybe just to place them in the context of the city. And to have a picture that was almost architectural, where the band were an adjunct to it.

"But you look at that picture, and you know what that band are going to sound like."

Cummins' most recent photo from Epping Walk bridge, from August 2020, looked towards modern-day Manchester

More recently, Cummins explains, he has revisited the bridge to reflect on how things have changed since his original photoshoot. Last year, he took a picture from the bridge looking back into Manchester, "to show how the city has developed in the time since then".

"Manchester was a fairly bleak, unattractive city that people wanted to leave pretty much as soon as they were old enough," he says. "Now people move to Manchester and want go [to its] university from all over the world. In 1979 they didn't."

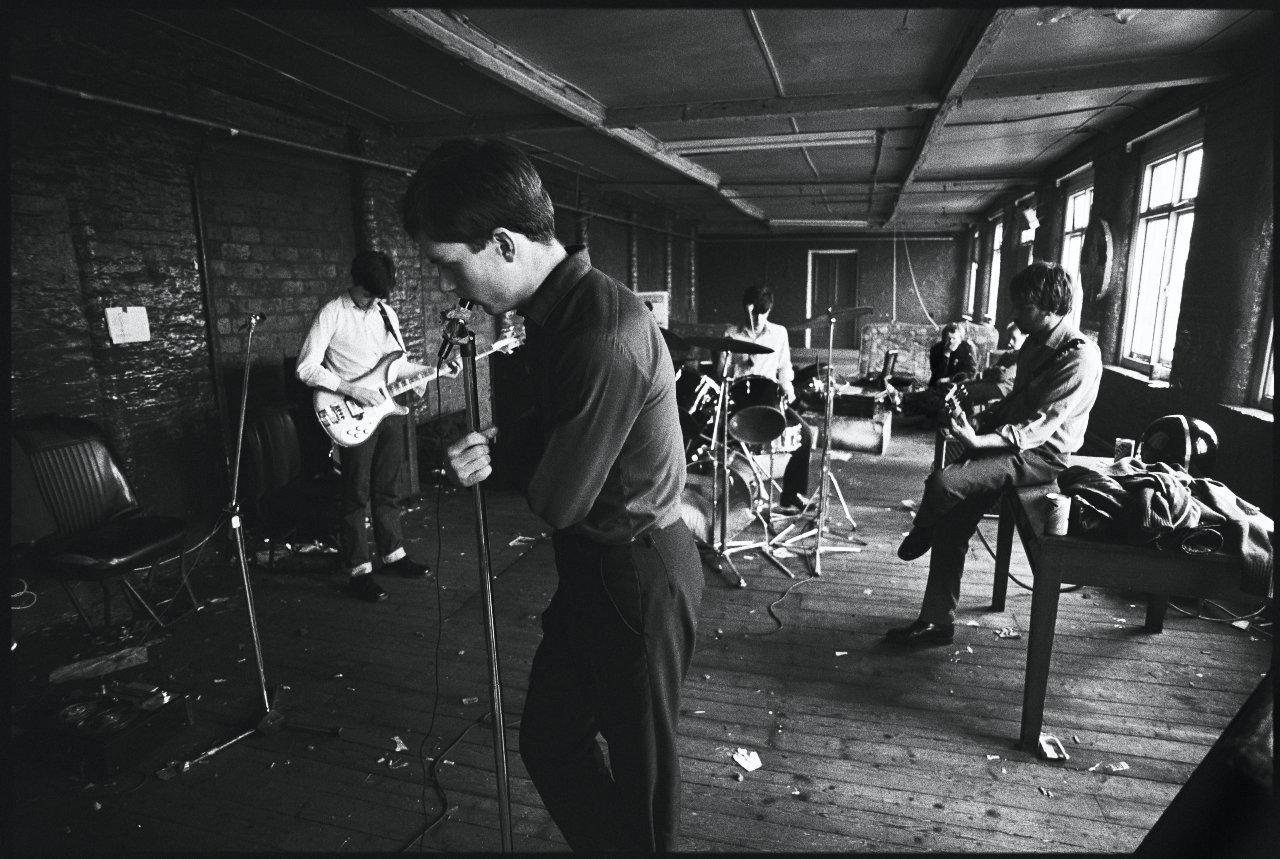

The band at TJ Davidson's rehearsal rooms where the video for Love Will Tear Us Apart was shot

"It just shows the contrast and begs the question... if Joy Division had met and formed in 2020, would their sound have been a different sound?"

Joy Division: Juvenes by Kevin Cummins is out now.

Related topics

- Published14 October 2021

- Published19 June 2021

- Published15 August 2013