'People fear for their jobs if they report bullies'

- Published

Toxic features actors portraying accounts of bullying by people working in TV and film

"People are frightened to reveal themselves, because they think they'll be blacklisted and won't get jobs if they report bullies at work," says film director Brian Hill.

The Bafta-winning director is so concerned about bullying in the film and TV industry, that he has made a short film called Toxic, which features four anonymous, haunting testimonies , externalvoiced by actors.

Disgraced film producer Harvey Weinstein is perhaps the most notorious case of toxic behaviour in that field of work.

Weinstein was sentenced to 23 years in prison for rape and sexual assault in 2020.

Actresses including Angelina Jolie, Salma Hayek, Gwyneth Paltrow and Rose McGowan spoke out against him before his New York court case.

But award-winning director Hill says problems in the industry persist - and many workers don't feel confident about voicing their complaints.

"People fear their income will suffer, and they won't get a good reference," he tells the BBC, the concern etched across his face.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The film and TV industry may look like a glamorous place to work, but Hill says it often isn't.

The reality for freelancers can be constantly having to prove themselves on short-term contracts, while working long hours away from home.

Hill, whose Bafta wins include one for 2002 Channel 4 drama Falling Apart, external, says he was spurred into making Toxic after his friend was "bullied out of a job in a big production company".

"Since the very beginning of my career, I was aware there were bullies in the industry," he explains.

"I've never been bullied myself, but you hear stories, and you talk to people who've been bullied. Like lots of other people, I'd just accepted it as part of the landscape."

Hill is also quick debunk the "myth of the artistic temperament", that someone is a "bully because they're a genius", adding: "It's such nonsense."

One of Brian Hill's anonymous interviewees described feeling "hunted" by her boss

A study published earlier this year, called the Looking Glass Report, external, surveyed the mental health of more than 2,000 people working in the UK film and TV industry.

Its results suggested that more than half (56%) of respondents experienced bullying at work in the last year, and its authors, the Film and TV Charity, external, said it was "alarming" to find that "bad behaviours abound or even flourish in this environment".

The report's findings also suggest that 16% of those who reported their experiences to colleagues said things "actually got worse as a result".

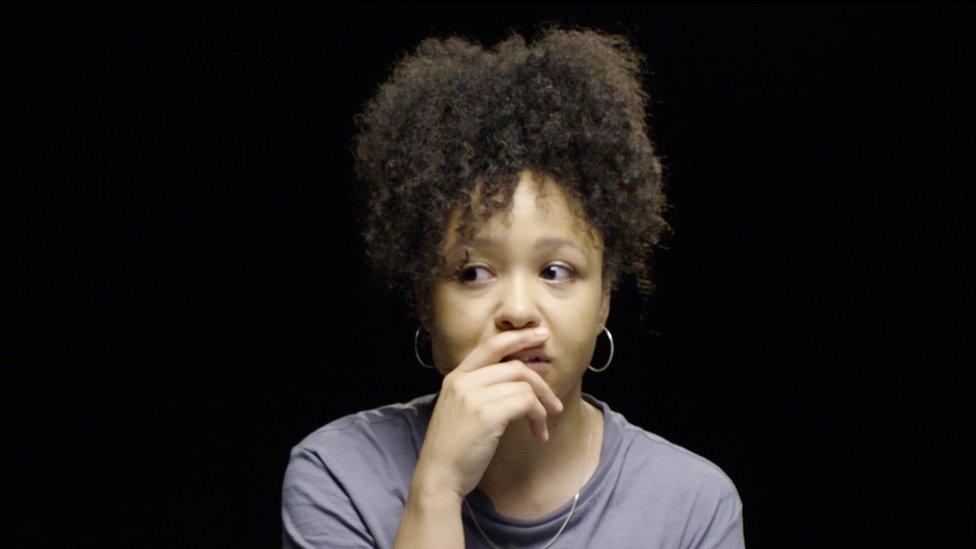

This actress portrays someone whose children asked her why she cried when her boss rang her

Hill decided to put a call out on social media for people to tell him their workplace stories, and about 50 came forward.

One interviewee describes feeling "hunted" by her boss.

She recounts being at home with her two young children: "We're just brushing our teeth and my phone starts ringing and it's her. I feel sick, and my children look at me and go 'What is it Mummy?' And I realise I'm crying."

Another says: "The people at the top won't intervene to deal with it [bad behaviour] as long as the bullies deliver. Ratings are more important than the welfare of the workers."

A third speaks about being "gaslighted" by a director, while the fourth - working on a reality TV show - spoke of "months of mental torture", adding he was "blamed" for problems when he raised them.

This may explain why Hill's interviewees wanted to stay anonymous.

This actor portrays a "new dad" working in reality TV, who didn't leave as he needed the income

"If management don't do anything about problems, I think at some point people stop raising their hands and naming names," he says.

His film has been shown by the Royal Television Society, and he is taking it to various TV and documentary festivals.

"The people who need to see it are the people who are at the top of the industry," he adds, saying he hopes it will be "seen and taken seriously by people who've got some power".

Brian Hill hopes Toxic will have an impact after it is seen by TV industry bosses

Matt Longley is also trying to change the culture of workplaces in the creative industries, but from the inside.

He used to work as part of the crew for movies including Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, World War Z and Batman film The Dark Knight Rises.

But he had an abrupt change of career after a colleague suffering from stress at work took his own life, about five years ago.

"I'd worked with him for probably two or three productions, and after that I kept in contact with him," Longley recalls.

"Before his death he wrote a letter to the industry about how lonely it was...I'd been out for beers with him three or four weeks before he took his own life - and would never have known," he says quietly.

Matt Longley became a wellbeing facilitator after a colleague took his own life

The shock of his friend's death resulted in him helping set up Six Ft From the Spotlight, external, about four and half years ago, a company which helps "promote positive working cultures" in the creative industries.

He also became a wellbeing facilitator., external, trained to offer advice on mental health risks and safeguarding, plus "resolution of challenging situations related to bullying, harassment and interpersonal conflict".

Explaining his on-set role, he says: "We recognised that people didn't have anybody to talk to. So we're independent from the production, a person that somebody can come to and talk to confidentially about anything that might be troubling them at work."

He says successful interventions by wellbeing facilitators can save productions money, due to fewer stress-related work absences.

Jennifer Smith, from the British Film Institute, would like wellbeing facilitators to become commonplace on set

He talks about the physical and mental toll of being in "fight or flight mode for a considerable amount of time", calling it "a horrendous situation to be in".

Working post-pandemic, while welcome, is also stressful as people are "working a lot harder, because obviously, the industry is so busy".

Longley would love to see all areas of the industry using wellbeing facilitators, but so far they are working as part of a pilot for the British Film Institute (BFI), external.

In February, the BFI announced it was providing additional funding for wellbeing facilitators on projects which it was backing financially.

The BFI's head of inclusion, Jennifer Smith, told the BBC: "The welfare of our cast and crew is paramount."

She has received "really positive feedback" about the role, adding she hopes it will be "normalised across the industry" like the intimacy co-ordinator role, "called for by Time's Up, external".

Time's Up, set up in 2018 by more than 300 actresses, writers and directors to help fight sexual harassment, called for intimacy co-ordinators to be compulsory on set when productions are filming intimate content.

But she adds that raising standards across the industry "and the interest we've seen gives me hope that this role being on every set is is within reach, but it's a long-term approach".

Theo Barrowclough, producer of BFI-backed film Scrapper, endorsed her view, saying working with Longley on their film set "proved to be a major coup".

"We were blessed with a brilliant crew, but even in those cases, every production needs to constantly hold itself up to being an inclusive and safe place to ply your craft," he explains.

"Matt's presence on set as someone the crew knew they could seek out, speak to confidentially and resolve issues with, made a big difference to me as a producer."

Jennifer Smith adds that Harvey Weinstein was the "catalyst which enabled us to galvanise the industry, and come up with a really concrete set of principles and guidance".

She thinks the wellbeing facilitator role is "another fundamental step forward in turning the tide for improving our workplace culture".

- Published6 July 2021

- Published21 July 2021