Thirteen Lives: Thai cave rescue actor Tom Bateman relives diving fears

- Published

[L-R] Viggo Mortensen, Tom Bateman, Colin Farrell play three of the British cave divers who were key to the rescue in 2018

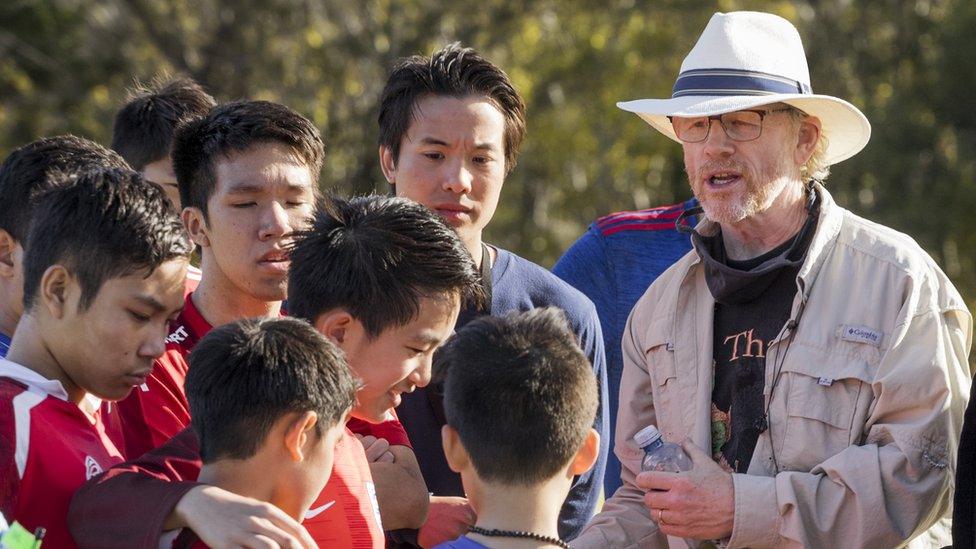

"The cast definitely all felt fear at various times," says director Ron Howard, who's revealing how he shot the rescue of a Thai boys' football team from a flooded cave, for his latest film.

Thirteen Lives tells the story of the perilous real-life rescue of the boys and their coach, trapped deep inside the Tham Luang cave network after monsoon rains came early in 2018.

"A couple of the actors admitted later they had some trying moments - but nobody had to leave the tank and breathe into a brown paper bag," the double Oscar-winner tells the BBC.

The film stars Viggo Mortensen, Colin Farrell, Joel Edgerton, Tom Bateman and Paul Gleeson as the divers, who guided the footballers along underwater spaces so narrow they could barely squeeze through.

The Thai caves are made of limestone, which accumulates water until it's saturated and then floods - in this case with calamitous results.

The actors had to replicate the conditions endured by the real-life divers.

Ron Howard insisted on authentic casting, and said the film had to respect and reflect Thai culture

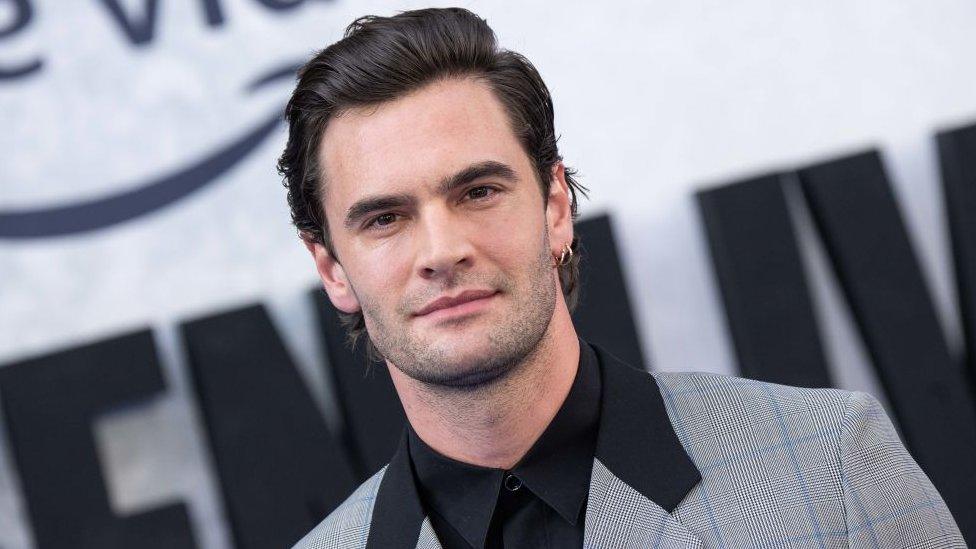

Bateman plays Chris Jewell, a British computer software consultant and expert cave diver, who was part of the rescue mission. The two kept in touch on set by text, so the actor could ask him about the role.

"Every single day was a challenge for me," Bateman says, adding he had scuba dived before, but had never done cave diving.

"I didn't quite realise how it made you feel... I suffer greatly from claustrophobia and I did meditate a lot," he says, on how he coped.

The actor is able to smile about it now, but he describes getting stuck underwater for about seven minutes while guiding a female diver, who played one of the boys, through a narrow passage.

The boys were heavily sedated for the rescue. Had they been awake, the likelihood is they would have panicked and injured themselves, and the diver.

"I had this amazing stunt double, she just had to lie there and have an actor take her through," Bateman says. "You think, 'If it's bad for me, imagine being her - she's completely helpless'.

Tom Bateman plays cave diver Chris Jewell

Then he got wedged between some rocks.

"I can remember feeling really hot and thinking, 'I'm underwater, but I'm sweating'," he says, as he watched his pulse racing on a wrist monitor. "I could just see my heart rate going up and up and up.

"But the beautiful gift of it was overcoming that... it's all in your head. It was a really safe environment, so getting over that hurdle of 'I can do this' is a small victory each time you do it."

Howard explains that some of the spaces were so small that despite "a great caretaking... you couldn't get the safety divers in with them all the time".

Bateman ultimately had to work himself free.

Relatives of the boys were seen praying near the Tham Luang cave in 2018

When news of the trapped boys broke, it flew around the world, and more than 10,000 volunteers gathered to help.

The Thai Government assembled a team of the world's most experienced cave divers, two of whom found the football team alive but very hungry - nine days after they disappeared.

Two Thai Navy Seals died - one while delivering air tanks, and another a year later, from an infection contracted during the rescue.

Early social media reactions to Thirteen Lives have been broadly positive. The Telegraph's film critic Robbie Collin called the film "compulsively watchable", external while singer Allman Brown added, external: "Everything on screen serves the incredible true story."

However, others say it's "not quite as suspenseful or exciting", external as some other rescue movies such as Apollo 13 or Everest, and critics' reviews will not be published until later this week.

Rick Stanton, who retired from the fire service in 2014, was made an MBE for his cave diving rescue services

While Howard hasn't tried cave diving himself, Mortensen really took to it. Bateman says his fellow actor "found it very calming," which is similar to how many cave divers say it makes them feel.

Mortensen plays Rick Stanton, a British diver who specialises in cave rescues. Stanton is what you might call a lateral thinker, having created a device called a side mount rebreather, which enabled him to dive to greater depths.

He was one of the advisors on the film, ensuring it was as accurate as possible, along with fellow British rescue diver Jason Mallinson.

When the boys became trapped, Stanton flew from the UK to help, along with British cave diver John Volanthen, played by Farrell.

They were the ones who found the boys alive, and their footage of that moment was shown around the world.

Finding the Thai cave boys and getting them out

Having navigated other global cave rescues, how did this one compare?

"This is way off the scale," Stanton tells the BBC. "In 2004, I rescued six British soldiers trapped in a cave in Mexico, external. That was a huge international incident - we had to dive them out.

"It was just a warm-up act for Thailand. It wasn't wasn't anywhere near the same scale, because Thailand involved boys. The magnitude of difficulty was not on the same same playing field."

Having become a bit disillusioned with cave diving after he retired as a firefighter in 2014, Stanton - by sheer chance - had returned to his sport a month before the rescue.

"I don't even believe in this stuff," he adds. "But you would think that my whole life had been preparing for that very event."

(L-R) Rick Stanton, Robert Harper and John Volanthen were key to the rescue

Stanton describes Mortensen as "absolutely a water person", who went swimming before filming, and had a basic diving qualification. Mortensen used Stanton's book, Aquanaut: A Life Beneath The Surface, as research.

Most of the movie was made on a specially built set in Australia, which recreated key parts of the torturous route, 2,950m inside the cave system.

Production designer Molly Hughes had slits built into the rock for the cameras, which were later disguised using computer-generated imagery (CGI).

"CGI could not really do much heavy lifting for us," Howard recalls. He says the actors insisted on doing all their own diving rather than using stunt doubles, which made filming easier.

"But it still ultimately became human beings trapped in a tiny space, trying to navigate in and around stalactites. The whole thing was much slower to shoot than I expected, and much more difficult to execute."

The boys were treated in hospital after their ordeal

Howard chose this story because, despite it being widely covered, he felt there was so much more to know.

"When I read Bill Nicholson's screenplay, it's one of those situations where I thought I knew more or less what had happened. And yet it told me I didn't know the half of it," he explains.

Howard is full of praise for the Thai Government's "lack of political interference and willingness to put pride aside, and open the situation up to volunteers".

"But make no mistake they were leading the entire time," he says.

The director was also very clear on was the portrayal of the Thai people and their culture in the film.

"I didn't want to take any chances," he says. "So there was no version of me accepting that this talented actor from Korea looks right enough that they could play the role. I just nixed that. I was rigid about casting."

Water was pumped out of the caves and diverted away from them

The film shows volunteers and experts diverting gallons of rainwater away from the caves onto nearby crops, which local farmers agreed to sacrifice.

Howard has made plenty of documentaries, and describes those made on the Thai caves rescue as "riveting" but adds: "The one thing scripted versions of stories can do is engage audience members' nervous systems. The actors, dialogue, camera work and music... open this pathway of empathy."

He wants the film to celebrate both the huge rescue effort and the international co-operation, as well as "giving audiences something thrilling, emotional and visceral for them to experience".

Thirteen Lives is released in cinemas on Friday 29 July and launches on Prime Video on Friday 5 August.

Related topics

- Published14 July 2018

- Published11 July 2018

- Published3 July 2018

- Published28 December 2018