When is a bestseller not necessarily a bestseller?

- Published

WH Smith's book chart is not based solely on how many copies have been sold

Authors and publishers all want to sell enough books to have a bestseller. But is a bestseller always actually a bestseller? Not necessarily if a publisher has paid to get on a shop's bestselling shelves, or staff base the rankings on what they predict might be popular.

Books are big business, and 2021 was a boom year. With more people buying and reading books during the pandemic, sales reached a record £1.8bn.

BBC Radio 4's Front Row programme has found that publishers often pay booksellers to be in their stores and, in one case, on its bestselling list.

WH Smith has racks of books in numbered positions under the heading "new and bestselling".

One publisher shared an email trail with Front Row that details its negotiations with the high street chain over a new book.

In the email, WH Smith asked for £2,000 in exchange for promotional space, including a position in the fiction chart - for as long as sales warranted it - and the book of the week slot.

The chain says its book charts are not solely based on how many copies have been sold.

Different charts

"Our charts combine sales performance with forecasts of which books our buyers anticipate will be bestsellers, which ensures our customers are offered the most relevant range in every store," the company says in a statement.

It adds that publishers can't buy "specific positions" in its book charts, which it says differ "across our estate reflecting our different customer bases in High Street, Travel [branches] and Online, plus local market conditions and consumer interests".

Author DV Bishop, whose debut novel City of Vengeance was published during lockdown, says that before he started writing, he had little idea about how the publishing world worked.

"As a member of the general public, if I walked into a store and I saw a bestseller list I would assume that's based on sales," he says.

"Now I'm working as an author and publishing, inevitably you end up finding a lot of things out about the industry you didn't know when you were just somebody wandering into a chain and thinking, ooh what am I going to buy?"

Paying for prominence in a shop or a place on a chart is described by some as an open secret in the publishing industry.

The publisher's email seen by Front Row also showed that WH Smith wanted a 60% discount on the recommended retail price and a 45p "retro fee" for every copy sold, taking the publisher's share of a £10 book down to below £4. In return, WH Smith would stock between 2,000 and 3,000 copies.

Veteran publisher turned author Mark Stay, who has 25 years' experience in the industry and now hosts the podcast The Bestseller Experiment, tells Front Row: "That sounds like a pretty standard deal for someone like Smiths, and you'll see similar deals with some of the supermarkets as well.

"This is the publisher deciding to take a hit on potential profitability in order to give the book a prominent position in store to get maybe a chart position in the chart that really matters - that's The Sunday Times bestsellers."

The Sunday Times list uses a service called Nielsen BookScan, which is based solely on sales.

Mr Stay continues: "That discount also enables Smiths to sell the book at a reduced price, so it might be in one of their promotions. So that 60% isn't just them hoarding away money. It enables them to offer the book at a greatly reduced price, which enables them to compete with the likes of Amazon, who discount quite deeply."

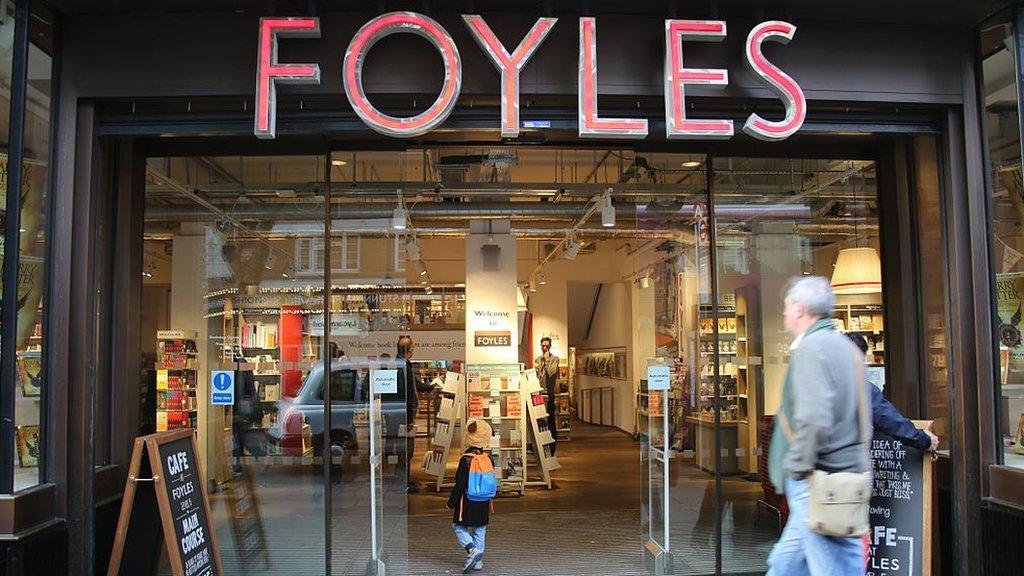

Waterstones' boss says he stopped charging publishers for prominent shelf positions

Independent book stores do not charge publishers for prominence or chart placings, while Waterstones chief executive James Daunt says his chain stopped doing so when he took over in 2011, despite the move costing £27m in lost deals.

"As a retailer, of course I'd love the money that I would be given by the publisher," he says. "The consequences of that, though, are terrible for the bookshops.

"So we stopped doing it at Waterstones completely. I've never taken a penny - as a result of which we have dramatically better bookshops. In fact, ever since we took that decision, the fortunes of the business have completely transformed."

He denies that Waterstones is having to negotiate bigger, sharper discounts with publishers to offset the missing millions. Instead, he says the company is primarily recouping that money by offering more books that people actually want to buy.

Previously, the chain was having to return an "immense" number of unsold books to publishers, which was "extremely expensive" and meant that, overall, they were "selling far fewer books", he says.

"So it's not actually about the terms. You can give up, in our case the £27m, and recoup that really very quickly simply by selling more books."

Meanwhile, supermarkets don't have bestseller lists, but some do charge publishers to be stocked in their stores, and often request different amounts depending on where the books are positioned in shops.

Tesco declined to comment, while Waitrose says it works "closely with our supplier to choose books that will appeal to our customers", and "regularly review these to ensure we're continuing to stock what our customers enjoy".

Asda says "the fee which publishers pay Asda… is decided on many factors", but that it "takes no payment from publishers to decide on the prominence of the book on the shelf".

Sainsbury's explains: "Publishers pitch books for varying distributions in store and then, at our discretion, we select the best offer for our customers. This is common practice across the industry."

The Booksellers Association hasn't responded to a request for a comment, and the Publishers Association declined to comment.

There is nothing illegal about the deals done by some stores and supermarkets.

Cat Mitchell, a lecturer in publishing at the University of Derby who has previously worked for a major UK publisher, says she was initially surprised to learn how the industry works, and that consumers would be "quite shocked".

Predicted sales

But she says the system self regulates because a publisher and a store would never exchange money for a "no hoper".

"The retailer has selected the books to start with, so they wouldn't put just any book in a chart if a publisher says, 'I will pay you a certain amount of money, please put this book at number one, or put it on the top shelf.'

"Neither the retailer nor the publisher want a situation where they're taking on board too much risk. A retailer doesn't want to waste shelf space… on a book that isn't going to sell many copies and isn't going to make the money.

"So there is obviously money involved, but the decision sort of comes down to the predicted sales and how well they think it's going to perform."

She adds that the words "bestseller" or "bestselling" can be ambiguous.

"One person I spoke to said something very interesting, which was that the public might see the words 'bestseller charts' and think it refers to the sales track record of those books," she says.

"Whereas [for] the retailer, it might mean that those are just the positions in the store where the books sell the best.

"So there's just a slightly different meaning going on here, which I think can potentially confuse the reading public."

Related topics

- Published9 August 2022

- Published15 June 2022

- Published21 April 2022

- Published7 October 2021

- Published12 November 2020

- Published7 September 2018