Jean-Luc Godard: Visionary director's life and films in pictures

- Published

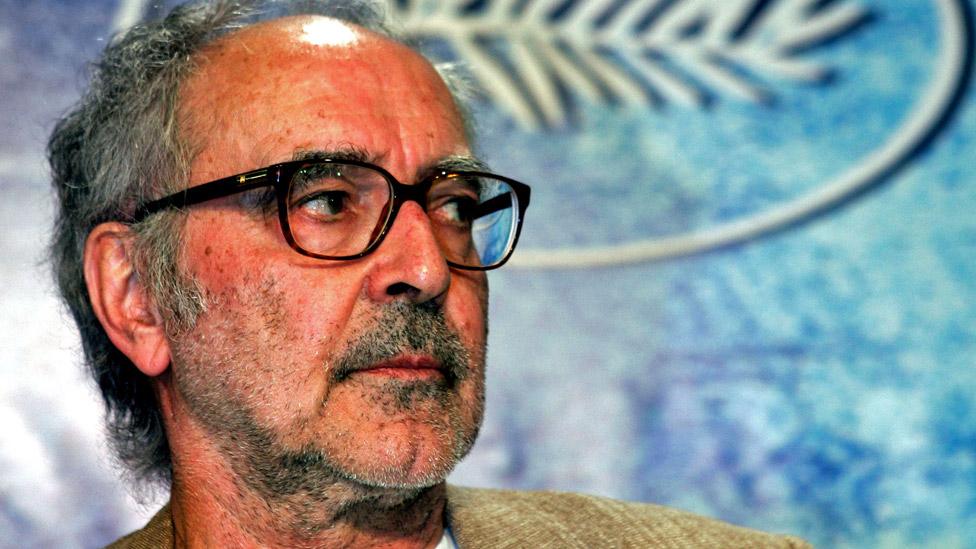

Jean-Luc Godard, who transformed cinema with his radical film-making style, has died at the age of 91. Here is a look back at some of his most seminal works.

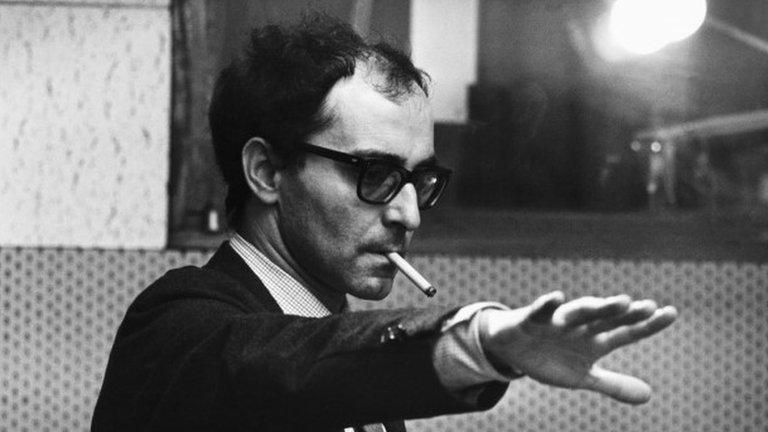

"Modern movies begin here," wrote film critic Roger Ebert of Godard's debut feature Breathless (A bout de souffle, 1960). "No debut film since Citizen Kane in 1942 has been as influential."

A tribute to American crime drama, it threw out the conventions of French cinema and embraced an unpolished, experimental style that employed handheld cameras, fast edits and dialogue that was often made up on the spot.

The plot wasn't anything new - telling the story of a gangster who shoots a policeman, and the girlfriend who ultimately betrays him - but the attitude and pacing were a breath of fresh air.

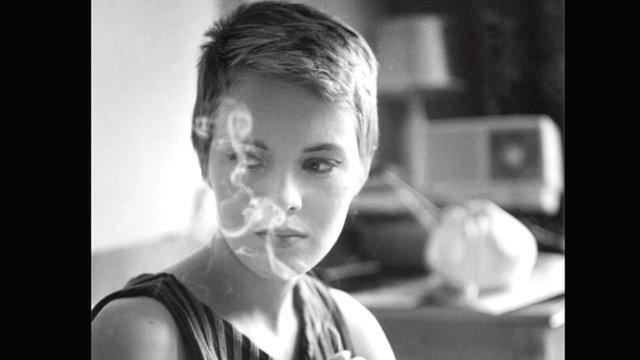

It made stars Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg, while its amoral, disaffected characters influenced the likes of Al Pacino, Robert De Niro and Quentin Tarantino.

Godard followed Breathless with The Little Soldier (Le Petit Soldat, 1961), a thriller that tackled the use of torture by both sides in the Algerian War.

Banned for two-and-a-half years by French censors, it was the director's first overtly political statement, leading him to coin the phrase: "Cinema is truth at 24 frames a second."

It was also the first film in which Godard directed his muse and future wife Anna Karina.

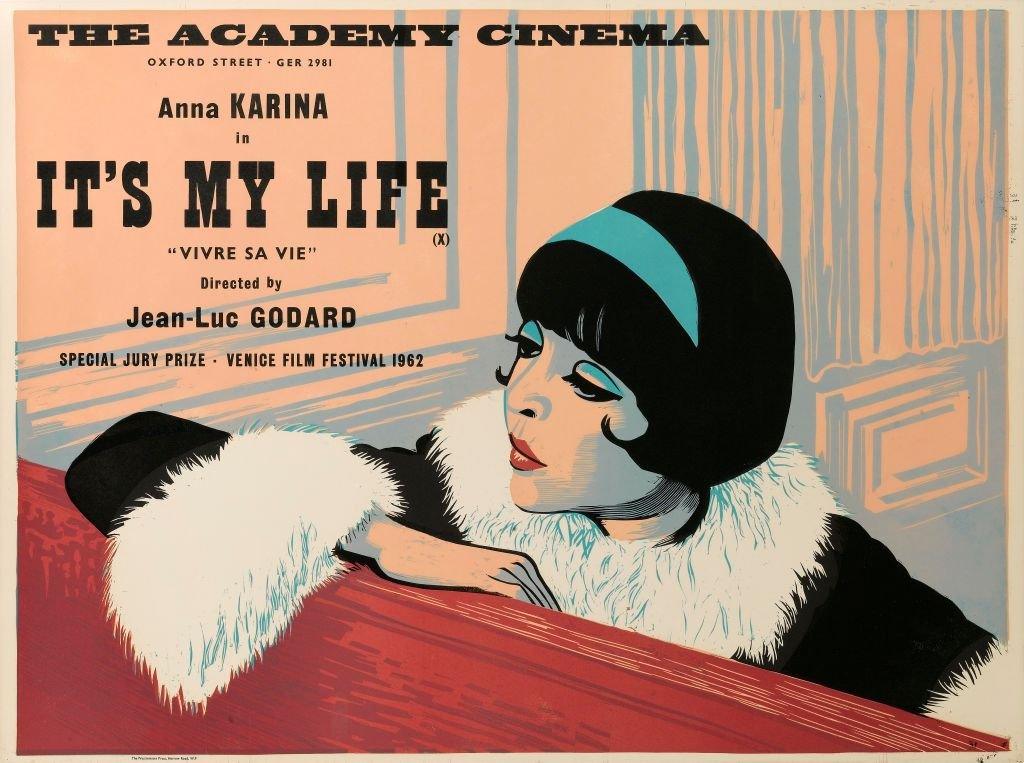

Karina also starred in It's My Life (Vivre sa vie, 1962) as a young Parisian, Nana, who aspires to be an actress but ends up a prostitute.

The story unfolds over 12 chapters detailing small but crucial events in Nana's life, with the camera often lingering on Karina's face in close-up.

Godard said the film was his attempt "to film a mind in action, the interior of someone seen from outside". It became one of his biggest critical and commercial successes.

Karina appeared again in 1964's Band of Outsiders (Bande à part), a radical reinvention of the gangster film, in which two restless young men (Sami Frey and Claude Brasseur) encourage a woman they're obsessed with to help them commit a robbery... in her own home.

The film includes two iconic sequences - a race against time through the Louvre art gallery, and a stylised line dance in a Parisian café, external, which was referenced in Pulp Fiction's infamous Uma Thurman/John Travolta routine.

Godard's 1963 film Contempt (Le Mépris) was his only venture into orthodox, big-budget film-making, starring France's most famous actress, Brigitte Bardot.

Adapted from Alberto Moravia's 1954 novel, it follows a failed playwright (Michel Piccoli) who is hired by a corrupt US film producer (Jack Palance) to write a screen adaptation of The Odyssey.

The writer is pressured to make the script more commercial, against the vision of director Fritz Lang (playing himself) - and the compromises he's forced to make sour his relationship with his wife (Bardot).

Contempt is often taken as a commentary on the machinations of the film industry, and Godard certainly faced uncomfortable compromises while making it. The opening scene, in which Bardot appears in bed with her husband, was added at the insistence of producers, who were furious that Godard had not included any nudity in his film.

In return, he made the scene deliberately un-erotic, shooting Bardot through a series of coloured filters, while underscoring the fragility of her character's marriage.

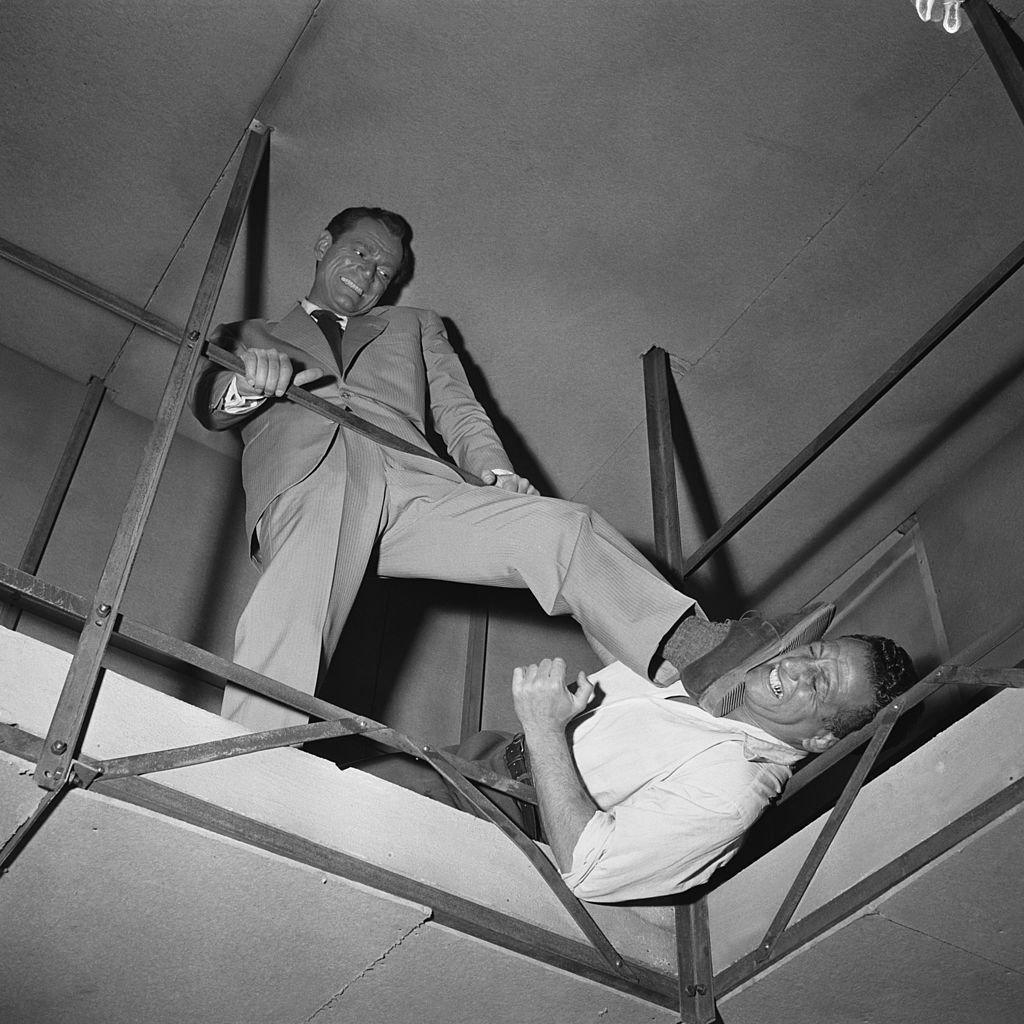

Contempt may have been Godard's most expensive film at the time - but he was not averse to dressing the set and moving props by himself.

He also helped bury Karina and Belmondo on a beach at Porquerolles Island while shooting 1965's Pierrot Le Fou.

Another thriller, it tells the story of an unhappily married man who flees Paris with his ex-girlfriend Marianne, who is in turn being pursued by hit-men from Algeria.

Godard's 10th film in six years, it was also his last crowd-pleaser of the 1960s, as he started to move ever further towards more radical cinema.

Also released in 1965 was the sci-fi film noir Alphaville, starring Eddie Constantine as a secret agent (codename 003) in a dystopian city where love and self-expression are outlawed.

He's on a mission to eliminate the mastermind of Alphaville, Professor von Braun, and destroy the dictatorial super-computer, Alpha 60, that controls its citizens.

Although the film was set in the distant future on another planet, Godard eschewed special effects and elaborate sets, simply shooting the darker corners of Paris as a substitute for the streets of Alphaville.

Week-End, released in 1967, was a hard-hitting denunciation of modern French society, a road movie about the end of civilisation, and a message that Godard was finished making commercial films.

Styled as a black comedy, it follows a bourgeois couple who set out to collect an inheritance from a dying relative, while the country crashes and burns around them.

It features one of the most famous sequences in cinematic history - an eight-minute tracking shot of a traffic jam where the camera travels almost three-quarters of a mile, suggesting that society has become trapped by its possessions.

The film closes with two title cards: "End of story", followed by "End of cinema", highlighting Godard's disillusionment with the cosy predictability of the mainstream. The following year, he helped to shut down the Cannes Film Festival in sympathy with the Paris student riots.

In 1968, Godard travelled to the UK intending to make a film about abortion. When that project fell through, he told producers he would only stay in London if he could work with the Beatles or the Rolling Stones.

Having failed to interest John Lennon in playing Leon Trotsky, he set up cameras in London's Olympic Studios to film the Stones recording what would become their classic album Beggar's Banquet.

There, he captured the goosebump-raising moment when they wrote Sympathy For The Devil. But the resulting film, One Plus One, was less a documentary about music and more a treatise on revolution, creation and destruction.

Footage from the studio was intercut with scenes of Godard's second wife Anne Wiazemsky spray-painting words like "Freudemocracy" and "Cinemarxism" onto cars; while another sequence featured children slapping the faces of white revolutionaries in a pornographic book shop.

Godard's original cut didn't include the full performance of Sympathy For The Devil. When it was inserted against his will, he was so incensed that he punched the producer at a screening in London's National Film Theatre.

In the 1970s, Godard teamed up with film-maker Jean-Pierre Gorin to create a collective they named the Dziga Vertov Group, after a pioneering Soviet documentary maker who they admired.

The films produced in this period - including The Wind From the East, Struggle in Italy and Vladimir and Rosa - were overtly Marxist in tone and struggled to find an audience.

After a period in the wilderness, the director began making successful narrative feature films again in 1979 with Every Man For Himself (Sauve qui peut (la vie)), which he called his "second first film".

The unwieldy plot centres on three adult characters and their problems with work and love - with Jacques Dutronc playing a character called Godard, who is an embittered, washed-up and sexist TV director.

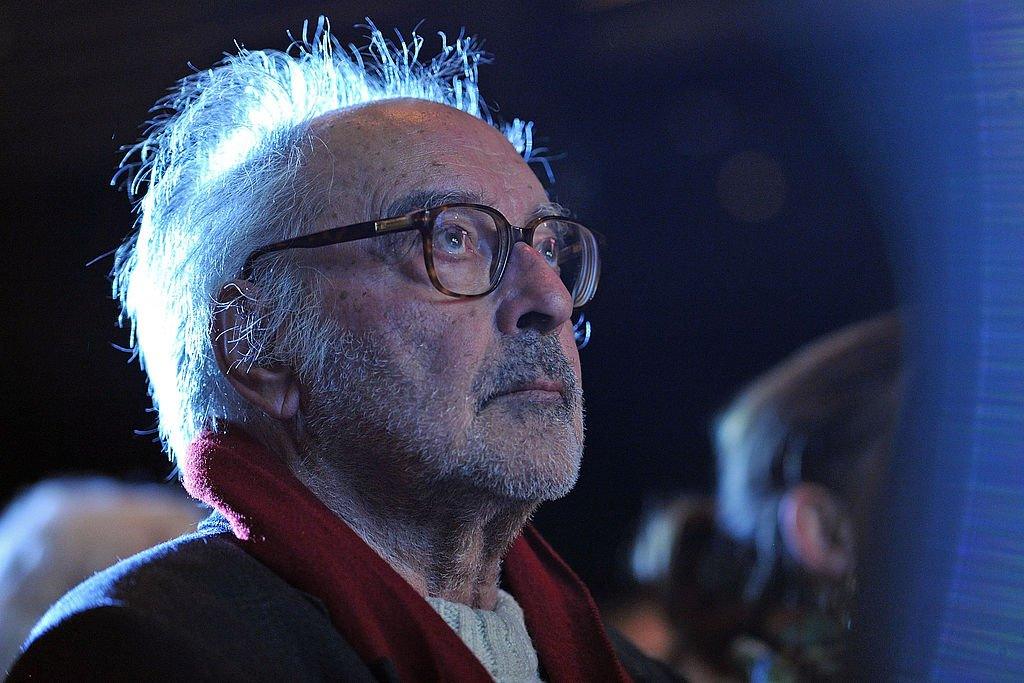

Premiered at Cannes in 1980 (pictured above), the film was described as "stunning," "beautiful," and "brilliant" by the New York Times.

Godard's most notable work in the 1980s was his "trilogy of the sublime", which consisted of three films that explored femininity, nature and religion: Passion, First Name: Carmen and Hail Mary.

The latter starred Myriem Roussel (pictured above) in a modern retelling of the birth of Christ, in which the daughter of a petrol station owner is visited by an angel who tells her she will give birth to the son of God.

The religious themes and scenes of full-frontal nudity upset many Christians, who protested outside screenings.

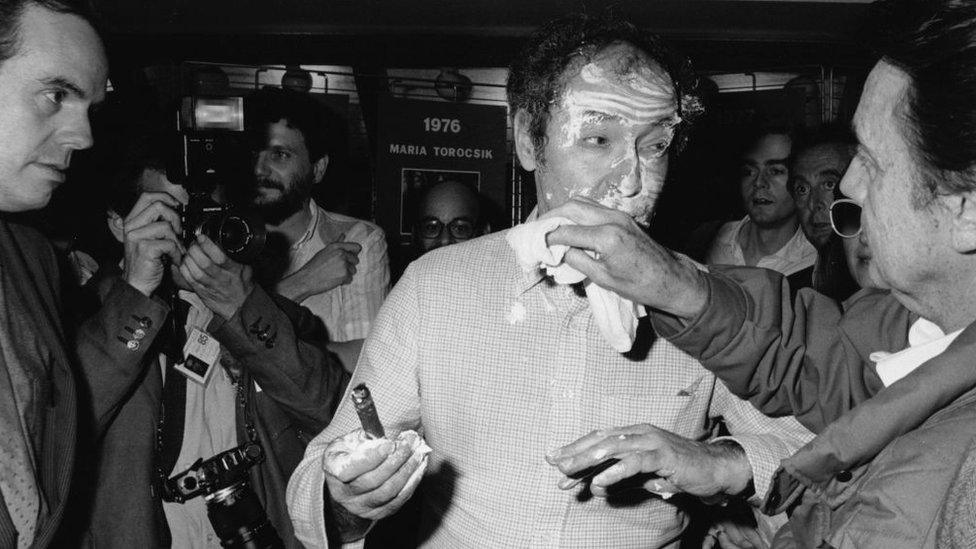

When Godard screened Hail Mary at Cannes in 1985, he was assaulted by Belgian anarchist Noel Godin, who threw a shaving cream pie in his face.

Godard responded: "This is what happens when silent movies meet talking pictures."

With protestors picketing screenings of the film in France, it was only a moderate success. The movie was also banned in Brazil and Argentina.

The director made few films in the 1990s, concentrating instead on his eight-part essay Histoire(s) du Cinéma - which first started to take shape in the late 1970s.

Described variously as "an epic poem", a "watershed composition" and "a sort of intellectual striptease", it is intensely personal, doggedly intellectual and staggering in its scope.

"Jean-Luc Godard took 30 years to compose his Histoire(s). It might take just as long to absorb it," wrote the critic Dave Kehr, external.

Godard returned to film in the 2000s, with meditations on war (Our Music, 2004) and the depiction of love on the big screen (In Praise Of Love, 2001).

2010's Film Socialisme (pictured above) was billed as his final feature, presenting many of his old arguments about the nation state, justice and history in a familiarly fragmented story.

"This film is an affront," wrote an infuriated Roger Ebert. "It is incoherent, maddening, deliberately opaque and heedless of the ways in which people watch movies."

2014's Goodbye To Language fared better, being named the second best film of the year by the influential Sight & Sound magazine.

Godard's first (and only) venture into 3D, its fragmented narrative tells the story of two lovers (and their dog, played by Godard's own pet, Roxy) and their increasing inability to communicate.

As their attempts falter, so to do the subtitles, the soundtrack and even the 3D image, which separates painfully to illustrate the character's disconnection.

The film was awarded the prestigious jury Prize at Cannes.

Godard was the recipient of numerous other awards, including an honorary Oscar in 2011, for which the inscription read: "For passion. For confrontation. For a new kind of cinema."

His final film, 2018's The Image Book, was given a one-off Palme d'Or, while he also owned a Golden Lion from the Venice Film Festival and a Golden Bear from Berlin.

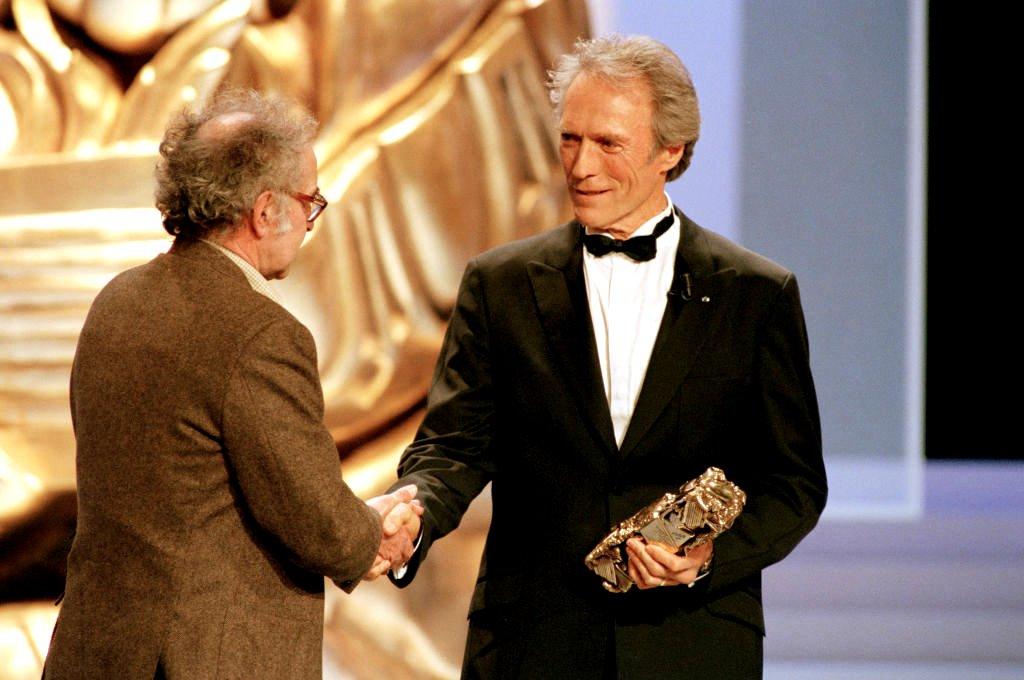

In his home country, he was awarded an Honorary César trophy twice, in 1987 and 1988 - with the latter presented by Hollywood legend Clint Eastwood.

But he turned down the French National Order of Merit, reasoning: "I don't like taking orders and I don't have any merits".

Follow us on Facebook, external, or on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

Related topics

- Published13 September 2022

- Published13 September 2022

- Published13 May 2018

- Published24 June 2015