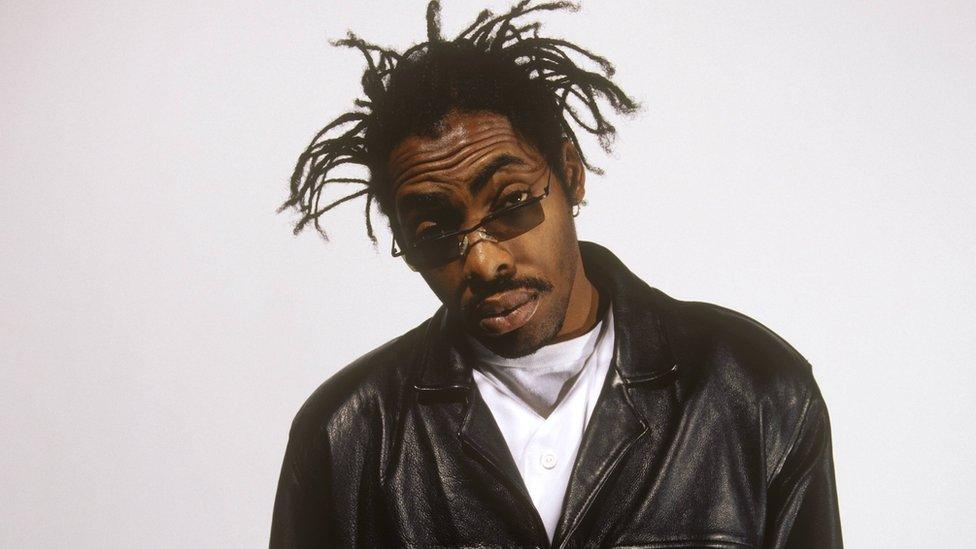

How Gangsta's Paradise changed the course of hip-hop

- Published

Gangsta's Paradise has sold more than six million copies worldwide

When Coolio first heard the demo that became Gangsta's Paradise, he had the same reaction as the rest of us.

"I was like, 'Damn, I really like this song.'"

The Pennsylvania-born, Compton-raised rapper was at his manager's house in 1995 to pick up a cheque, when he noticed producer Doug Rasheed messing around with the song in another room.

"So I went to Doug said, 'Yo! What's this?'"

"He said, 'It's just a song we're working on',

"And immediately I said, 'It's mine'. Just like that.

"I freestyled the whole first line, then I sat down, I picked up a pen and I started to write."

Released in August 1995, and boosted by a memorable video starring Michelle Pfeiffer, the song immediately ruled the airwaves.

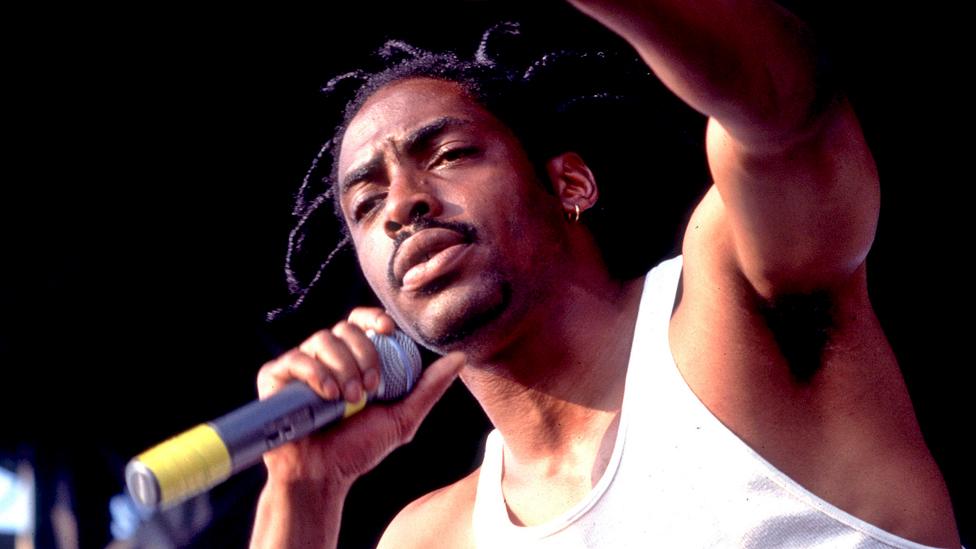

Those lurching stings, the other-worldly choir, and that soaring hook, combined with Coolio's distinctive, confessional storytelling, made it an instant classic.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

It was the first "serious" rap song to top the UK and US charts, opening the door for acts like 2Pac and the Notorious B.I.G, who, until that point, had been considered too abrasive for the mainstream.

And its appeal has never lessened. The biggest-selling single of 1995 in America, Gangsta's Paradise has now been streamed more than one billion times on both Spotify and YouTube.

"I thought it was going to be a hood record," he told The Voice in 2017. "I never thought it would crossover the way that it did - to all ages, races, genres, countries and generations."

And yet... Gangsta's Paradise faced several hurdles on its way to the top. Here's how it unfolded...

Coolio was born Artis Leon Ivey, Jr in Pennsylvania, and moved to Compton in South Central LA as a boy. Suffering from chronic asthma, he became a bookworm and excelled at school.

"I lived in that library, man," he told Rolling Stone, while visiting his old neighbourhood in 1995, external. "I read every kid's book they had in there. I even read Judy Blume."

That changed when he turned 11 and his parents divorced. Seeking a way to fit in, he fell into the gangster lifestyle and adopted a menacing, street-tough persona. A few years later, he was busted for bringing a weapon into school. Before he turned 20, he had served time behind bars for larceny.

Later, Coolio studied at Compton Community College and discovered rap. He took his stage name, Coolio Iglesias, from Latin heartthrob from Julio Iglesias, and released a few singles on the local scene, but drug abuse derailed his career.

In his 20s he moved to San Jose to live with his father, while working as a firefighter; and later credited Christianity for helping him overcome his addiction to crack.

Still enamoured with rap, he made a guest appearance on WC and the Maad Circle's 1991 debut album, Ain't a Damn Thang Changed; then joined a collective called the 40 Thevz before signing a solo deal with Tommy Boy records - the influential label that played home to De La Soul, Naughty By Nature and House Of Pain.

His first album, It Takes a Thief, arrived in 1994, and was praised for its combination of funky grooves and socially-conscious lyrics. The musician's message was exemplified by the "hilarious" video for Fantastic Voyage, said Source magazine.

"As the Lakeside groove carries you along, Coolio piles about six milion people into the trunk of his '64 and takes them to a magical land where race, poverty, gangs and sexual orientation don't matter and everybody was cool."

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Hip-hop's gatekeepers were not interested in such idealism. Ivey's anti-violence, pro-acceptance stance somehow made him "soft". He earned the unwelcome nickname "Un-Coolio".

But then came Gangsta's Paradise.

One day, Doug Rasheed pulled out his copy of Stevie Wonder's 1976 double-album Songs In The Key Of Life and cut a sample from Pastime Paradise, a bleak and anxious track that was one of the first songs to replace an orchestra with synthesized strings.

Rasheed added a crunching beat and a menacing synth bass, then took the track to singer Larry "LV" Sanders, who laid down a vocal for the chorus.

"I came in singing 'Pastime Paradise,' but then I changed it up to 'Gangsta's Paradise,'" he told Rolling Stone for an oral history of the song, external in 2015.

"I did my parts, all the vocals and the chorus, and I did the choir. That whole choir that you hear was actually me - I did all the parts from soprano down to tenor to the bass."

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

LV wanted a rapper to appear on the track, and offered it to his friend Prodeje, who declined. Then Coolio overheard it.

Mesmerised, he started writing lyrics straight away. The opening lyric, which riffs on Psalm 23, external, came to him instantly: "As I walk through the valley of the shadow of death/I take a look at my life and realise there's not much left."

"I freestyled the whole first line, then I sat down, I picked up a pen and I started to write," he told the YouTube series Hot Ones in 2016, external.

"It was divine intervention. I was an instrument and the song was the entity. It wrote itself."

Coolio was 30 at the time the song was written, but the narrator is 23 and he doesn't know if he'll live to see 24. He was "raised by the street", immersed a life of crime and retribution. If anyone crosses him, they'll end up "lined in chalk".

But the story never glorifies the gangster lifestyle. The narrator prays every night, aware that he's trapped. In the final verse, he accuses the system of letting him down.

"They say I gotta learn, but nobody's here to teach me / If they can't understand it, how can they reach me?"

'Just an album track'

It's a bleak story. One that could only have been told with the perspective Coolio gained from his teenage years. And the rapper bristled when his song was lumped in with the so-called "gangster rap" scene.

"I'm trying to get rid of that jacket that's been put on my back - that I'm a gangsta rapper," he said in 1995, external. "That's not my thing.

"My thing is to be true to myself and try to educate and entertain kids. When I make references [to the gangster lifestyle], I'm trying to get kids' attention using language they want to hear.

"Then I can take them to a deeper level. I'm just trying to get a better understanding of myself and a better understanding of other people."

Gangsta's Paradise was a stark departure from the feel-good funk of Coolio's first album and, at first, his record label weren't sure what to make of it.

"I called my A&R at Tommy Boy Records, and I played it for him. He said, 'It sounds pretty good - I think it would make a good album cut.' Those were his exact words!"

Incensed, the star's manager decided to shop the song around to movie studios. It nearly ended up on the soundtrack to the Will Smith film Bad Boys, but was eventually placed in the Disney movie Dangerous Minds - the true story of a former Marine who turns around a troubled inner-city high school by teaching them poetry and Bob Dylan lyrics.

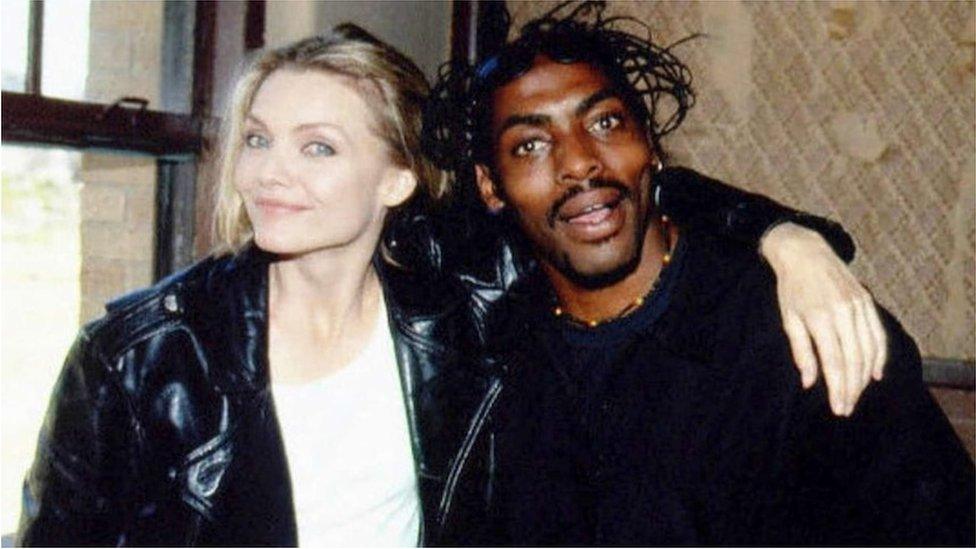

A lukewarm retread of Dead Poets Society, it was allegedly testing badly with audiences until Coolio's song started getting played on MTV. The video, like the film, starred Michelle Pfeiffer, who went face-to-face with Coolio as a camera spun around them.

"She was real nice," Coolio told Kiss FM's Rap show at the time. "She brought her son down to the shoot with her and she was cool. We had no problems."

Michelle Pfieffer and Coolio on the set of the Gangsta's Paradise video

He was less enamoured with the movie itself, though.

"I hate those kinds of movies where, you know, the great white hope comes into the inner-city neighbourhood and saves the little children - 'Ooh la la, hey Santa Claus!' or whatever, all those kinds of things put it in play," he told Yahoo two years ago, external. "Those kinds of moments happen very few and far between. It's not that many people that care about each other [in real life]."

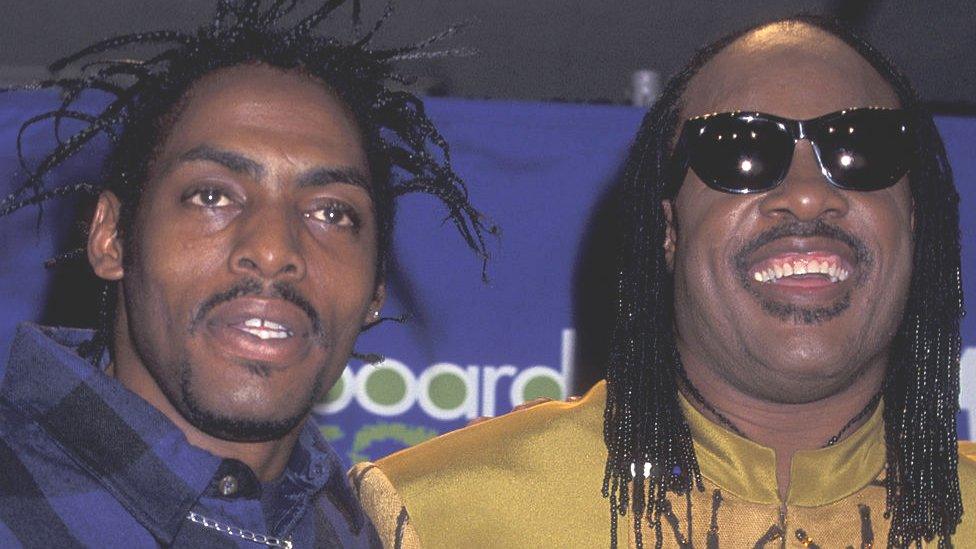

According to Rolling Stone's oral history, the producers of Dangerous Minds, Coolio was paid $100,000 (£92,000) for Gangsta's Paradise. There was only one problem: Stevie Wonder hadn't cleared the sample.

"When Stevie heard it, he was like, "No, no way. I'm not letting my song be used in some gangster song,'" the star recalled.

Luckily, Coolio's then-wife Josefa Salinas, knew Wonder's brother. "I guess he had been trying to tap that for years," he joked in the Rolling Stone article.

"She made a call to him, got a meeting with Stevie and talked him into it. His only stipulation was that I had to take the curse words out."

Coolio and Stevie Wonder performed the song together at the 1995 Billboard Music Awards

That edit undoubtedly changed Coolio's life. A profane version of Gangsta's Paradise would never have been played on pop radio, or entered heavy rotation on MTV.

When it hit number one, it opened up new possibilities for hip-hop... although, to some, it marked the end of an era.

"America suddenly realised it could sell non-party rap to Brit panty-waists, and that's exactly what it's done ever since," wrote music journalist Garry Mulholland in his book This Is Uncool: The 500 Greatest Singles Since Punk And Disco.

"In many ways, Gangsta's Paradise signalled the end of gangsta, or 'reality' rap as a cult. It lost the allure of the forbidden when you mum started singing along."

Coolio was ambivalent about the song too, often lamenting how its success overshadowed his other work.

"It's a blessing and a curse at the same time," he said. "For people that really like Gangsta's Paradise, that's all they really want to hear."

In recent years, however, the musician came to appreciate the song's legacy, and his role in hip-hop history.

"People would kill to take my place," he said in 2018, external.

"I'm sure after I'm long gone from this planet, and from this dimension, people will come back and study my body of work."

Follow us on Facebook, external, or on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published29 September 2022

- Published29 September 2022