Beatles' Revolver: 'It's time travel' says Giles Martin

- Published

Last month, in Abbey Road's legendary Studio 3, Giles Martin performed a magic trick.

He was there to unveil something that should have been technically impossible - a remixed, reinvigorated version of The Beatles' seventh album, Revolver.

The band's first record after announcing their retirement from live performance, it saw them explore new sonic territories and styles of composition, from the chamber pop of Eleanor Rigby to the kaleidoscopic eruptions of Tomorrow Never Knows.

It took 300 hours to record (almost three times as long as the Beatles' previous album, Rubber Soul) as they experimented with tape loops, back-masking and LSD.

Fans have long been clamouring for an expanded edition of the record - but there was a problem.

Unlike their later albums, the Beatles recorded Revolver's basic tracks direct to tape, standing in a circle, playing as a band. That made it almost impossible for future generations to separate and isolate the instruments and vocals.

Until now.

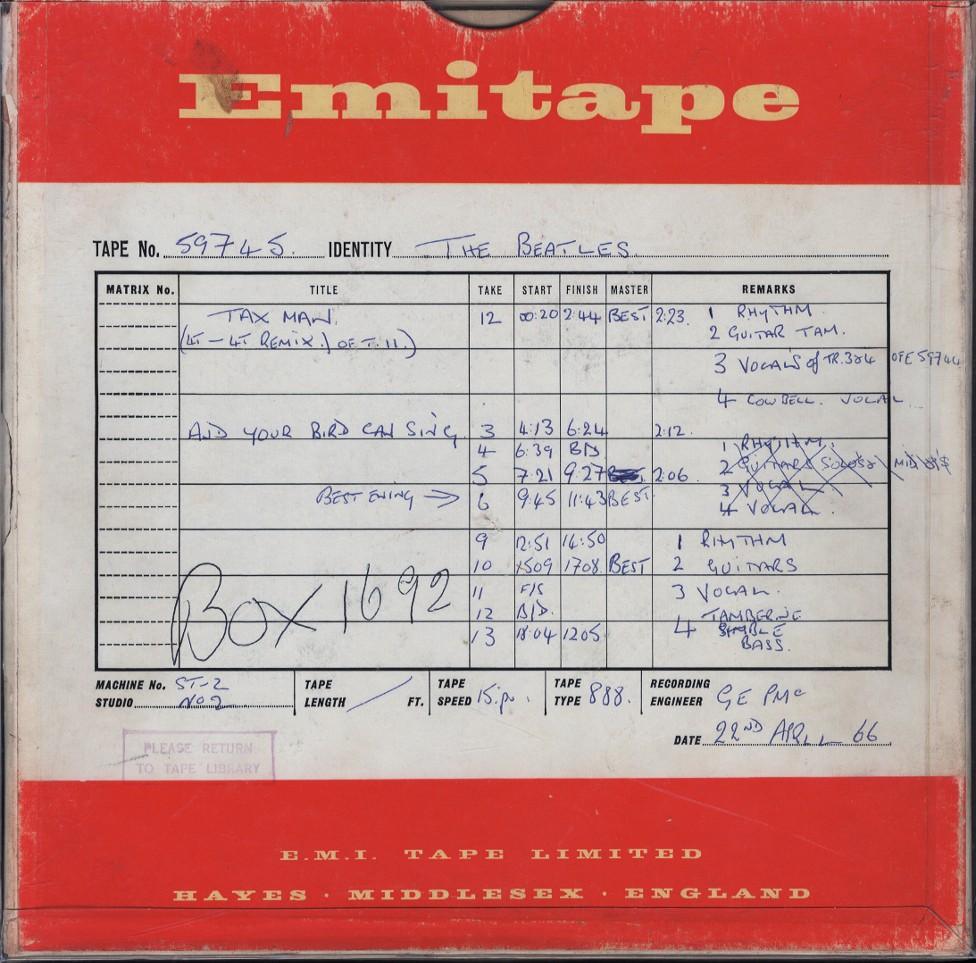

Back in Abbey Road, Martin cues up Taxman, Revolver's tense and brittle opening track.

"What would it sound like without George Harrison's guitar?" he asks, pulling down a fader that eliminates him from the mix. Next, he drops out Paul McCartney's bass, so the only thing you hear is Ringo Starr's drum kit.

It's a revelation. The kick drum pedal squeaks on every beat, and the snare reverberates off the studio walls. No-one, not even Ringo, would have heard those details at the time.

Martin compares it to being given a cake and having the ability to break it down to its constituent ingredients. And it's only possible because of the technology that Peter Jackson's audio team created for the Get Back documentary.

"The dialogue editor [Emile de la Rey] was doing a really good job of removing the guitars from the dialogue, and I said to him: 'Let's have a look at Revolver. Can you separate the guitar, bass and drums?'" says Martin.

"He did a rough pass and it was so much better than anything I've ever heard. I said: 'OK, we need to work on this', and it got to a stage where it became extraordinarily good."

Martin isn't clear on how the de-mixing process works, but he knows it involves elements of AI and machine learning.

"It has to learn what the sound of John Lennon's guitar is, for instance, and the more information you can give it, the better it becomes.

"So we were going through the tapes just looking for bits where someone played a guitar with no-one else playing - and that's how the computer can can go: 'Okay, this is what I'll extract'.

"But all that means is that, when people listen to the record, the band don't have to be on each other's lap."

For his new version of Taxman, Martin discards the original's gimmicky stereo mix, which placed the instruments in the left speaker and the vocals in the right, Now, the band spreads out across the soundstage, putting the listener in the middle of a Beatles performance.

It's a technique Martin applies to the whole album. Compared to the muddy CD mixes that emerged in the 1980s, the new Revolver is bristling with life, full of presence and attack.

"People forget that it's just a young band playing in the studio," says Martin. "Everything is fairly aggressive. Everything is in your face. Everything the Beatles recorded is a little bit louder than you think it is."

Eleanor Rigby is a perfect example. Instead of using the string section as a soft underscore, Paul asked them to play in sharp, staccato stings inspired by Bernard Herrmann's score for Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho.

"Which is a funny influence if you think about it - you take the shower scene with a woman being stabbed and put it on Eleanor Rigby," reflects Martin.

An expanded, deluxe edition of Revolver captures the strings being recorded at Abbey Road, with Giles's father George Martin arranging the musicians on the fly.

"Do you want them to play the chords without vibrato?" he asks McCartney, who listens to several options before declaring he can't tell the difference.

"All those years of learning," the musicians grumble good-naturedly, "and he says it sounds the same."

McCartney eventually opts to lose the vibrato, giving the recording its razor-sharp immediacy.

"What impresses me is the speed of thought," says Martin. "You have to remember that 10 minutes before that conversation, no-one would have ever heard the Eleanor Rigby strings before. It's an amazing session."

It's one of many insights on the box set, from a rehearsal of And Your Bird Can Sing where the band can't stop laughing - "It reminds you that maybe there was some pot smoked during that time" - to a previously unheard demo of Yellow Submarine.

While Beatles historians have always attributed the song to McCartney, the newly unearthed work tape is pure Lennon. He strums a sad acoustic guitar figure and sings: "In the town where I was born / No-one cared, no-one cared..."

It's unrecognisable from the bumptious singalong it became - the words Yellow and Submarine are conspicuously absent - but Martin says the development of the song shows the Beatles at their most harmonious.

"There's an acceptance of 'OK, I've got this very sensitive and sad song, and Paul's going to turn that into a hit for children'. That didn't happen later on Abbey Road or Let It Be, and I think that's the key to Revolver: They absolutely accepted each other's direction."

The scale of their confidence was such that the first song they tackled in the studio was Lennon's nightmarish sound collage Tomorrow Never Knows, full of sitar drones, processed vocals and unholy seagull calls (actually a speeded-up recording of McCartney laughing).

Derided at the time, it's now recognised as a landmark of psychedelia, and a pioneering example of sampling and manipulating tape loops.

"And the thing about the Beatles is they never tried it again," says Martin. "I can't work out the mentality of it, in all honesty, what was going through people's minds.

"Even my dad, you know? He was always pretty strait-laced, but he just accepted 'Okay, well this is what we're doing'!

"I always think it's like surfing, in a way. There's been very rare times in my life where I've done creatively good things but most of the time, I'm treading water or trying to avoid getting hit by the waves.

"But the Beatles spent their whole time on the crest of a wave."

Which raises the question, why remix the album at all?

There are Beatles fans who refuse to listen to Martin's remasters and remixes, accusing him of rewriting history.

"I kind of embrace them because, in a way, they're absolutely right," Martin says. "There's no reason why you should listen to these mixes. It's not like I've deleted anything."

Instead, he likens the process to sandblasting the exterior of St Paul's Cathedral, and seeing it as Sir Christopher Wren would have done in 1697.

The surviving Beatles supervised the mixes (McCartney told him off for being "too polite" with And Your Bird Can Sing) and the idea is to preserve their songs for a new generation who primarily listen on headphones, where the original hard-panned version of Taxman is awkward and disorientating.

"I remember mixing Strawberry Fields and the young guy working at Abbey Road with me had never heard the song before," says Martin. "And there's no reason why he should. It's bloody old.

"But there's also no reason why a 26-year-old Paul McCartney shouldn't sound like a 26-year-old does now.

"So essentially, what we're doing is time travel. And I like that even now, 56 years on, we're trying to break new ground. Because that's what the Beatles did."