Treasure definition may be broadened to help museums

- Published

Heritage Minister Lord Parkinson and Curatorial and Learning Officer Sarah Harvey observe the Birrus Britannicus Roman figurine at Chelmsford Museum in Essex

The legal definition of "treasure" could be broadened in a bid to help museums acquire important items.

The wording could be changed following a surge in the number of detectorists unearthing historical artefacts.

Arts and Heritage Minister Lord Parkinson said the proposed changes would apply to the Treasure Act 1996.

He noted some items have been lost to private ownership, rather than displayed publicly in museums, due to the existing wording.

Under the current definition, an item is categorised as treasure if it is at least 300 years old and made at least in part of precious metal, like gold or silver, or part of a hoard.

The proposed changes would mean that this will be amended to cover exceptional finds of at least 200 years old, regardless of the type of metal they are made of.

If a coroner assesses an artefact as meeting the legal definition of treasure, it can be acquired by a museum rather than sold privately to the highest bidder.

Lord Parkinson said the Treasure Act has "saved around 6,000 objects which have been shared with museums, more than 220 museums around the country".

"But, at the moment, the definition of treasure is very specific," he added.

The Roman figurine Birrus Britannicus does not meet the current definition of treasure, but was saved by another mechanism

"An item has to be more than 300 years old, it has to be made of a precious metal or part of a hoard," Lord Parkinson said. "We want to widen that so that other important objects don't fall through the net.

"We're proposing to change the law to make the definition something that is more than 200 years old, to say it can be made of any type of metal but also bringing in a new test of significance.

"So, to say if this is an item which is significant to a part of local, national or regional history, or if it's connected with a particular individual or event, then it can be classed as treasure too and it can be shared with the public in a museum."

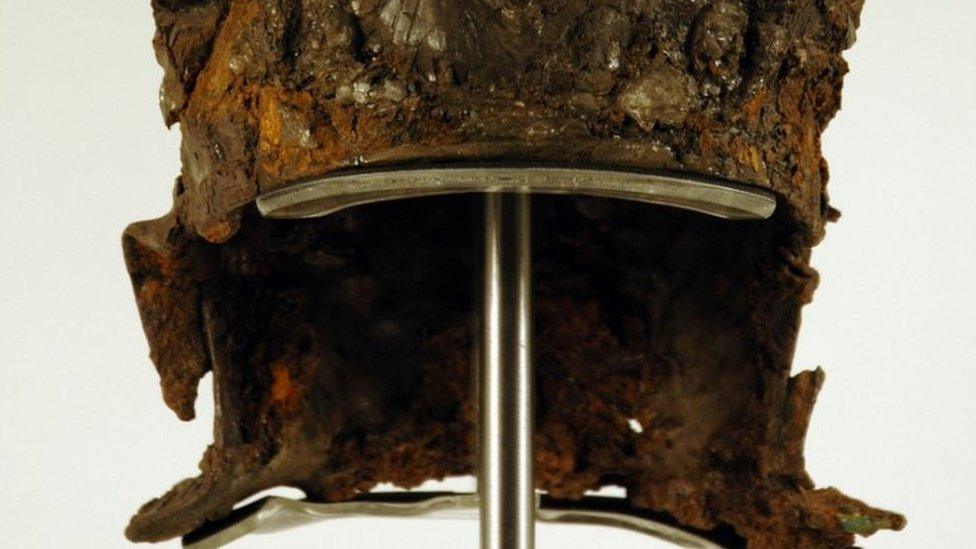

He cited the Crosby Garrett Roman cavalry helmet, discovered near Penrith in Cumbria, as an example of an artefact sold to a private bidder as it did not meet the current definition of treasure.

"It was made of metal but not of precious metal so it wasn't classed as treasure under the current definition," he said. "We want those sort of items to be shared."

He added: "Most of the finds of treasure are by detectorists, so we're seeing more objects being discovered and we're seeing more examples of things that don't currently meet the definition being lost or being at risk of being lost to the public.

"We want to make sure they can be saved for museums.

Lord Parkinson said displaying treasures to the public "can inspire future generations"

Chelmsford Museum in Essex has a Roman figurine in its collection that does not meet the current definition of treasure, but was saved by another mechanism.

Lord Parkinson said the copper alloy piece, discovered in Roxwell, Essex, wears a hooded cloak known as a Birrus Britannicus that people wore in Roman Britain.

"It tells you about the weather at the time, it tells you about fashion, it tells you about the exports from Britain into the Roman Empire," he said.

"These sorts of objects should be shared with people in museums so they can inspire future generations."

Sarah Harvey, a curator at Chelmsford Museum, said that because the Roman figurine is made of a copper alloy, it did not count as a precious metal.

She said that the finder, a detectorist, was planning to sell it abroad, and the museum had to go through "quite a lot of administrative steps to keep it in this country".

"With this new definition of treasure we won't have to go through all of those steps, we would have first rights to acquire that sort of item," she said.

Nicola Potter, of the Cotswold Heritage and Detection Society, is typical of a metal detectorist in the UK when she says she has found "lots of rubbish and lots of really interesting finds".

Nicola Potter first took metal detecting two years ago

The 48-year-old from Cheltenham started using a metal detector two years ago and says she does it at least once a week.

A few weeks ago, she unearthed a silver Celtic stater - a small coin decorated with a triple-tailed horse that was used by a local tribe in around 20BC.

The mother-of-two, who works in financial services, says she cried when she found her first gold ring and first silver hammered coin.

"It's just an incredible feeling, just to hold something in your hand ... that hasn't seen the light of day for over 2,000 years," she said.

"It's a ridiculous feeling, it's wonderful, it puts a massive smile on your face."

Mrs Potter said she thought the changes to the Treasure Act were needed "because there will be far too much history that's being lost by people not declaring it."

The 48-year-old supports the changes to the Treasure Act

Related topics

- Published21 November 2019

- Published25 July 2020

- Published30 April 2021

- Published3 August 2022