Adam Lambert: 'I didn't think I'd have a shot'

- Published

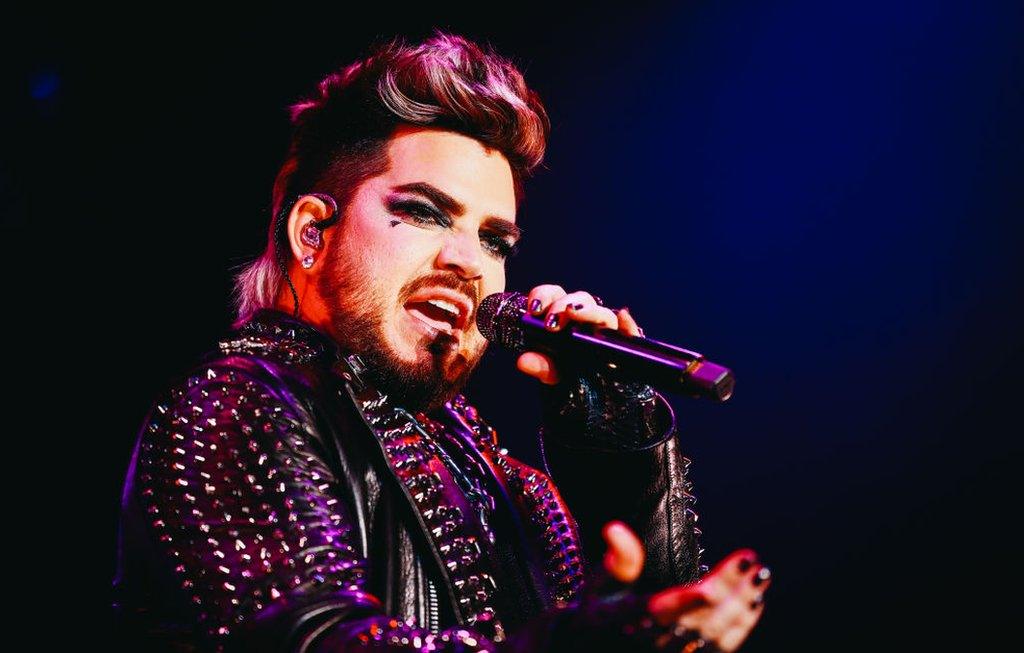

Adam Lambert juggles his time between Queen, his solo career, The Voice US and ITV talent show Starstruck

Once upon a time, Adam Lambert's record label asked him to record an album of 1980s new-wave cover versions.

It wasn't a terrible idea. Anyone who'd heard Lambert cover Tears For Fears' Mad World on American Idol, external knew how suited he was to that era of melancholy synth-pop.

But at that stage, two albums into his career, a covers album seemed like capitulation. Worried it would damage his credibility, the singer quit the label.

"This is the only kind of release they are prepared to support," he told fans in an open letter, but "my heart is simply not in doing a covers album".

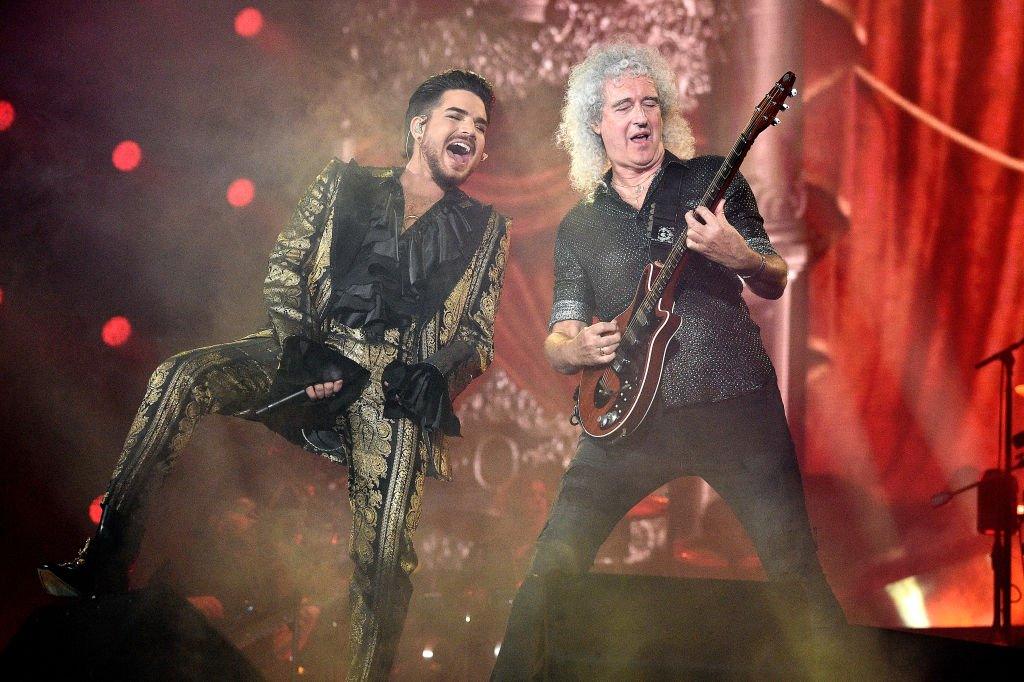

A decade later, his position has changed. Lambert is arguably more famous as Queen's new frontman than as a solo artist; and his new album, High Drama, is entirely comprised of covers.

"Well, look, I mean, timing is integral," he protests. "At the time they wanted me to do that, I was not interested and that was that.

"I'm at a point now where the idea came up, and I thought, 'That sounds like a fun challenge'. The idea was to find some songs and flip them on their their heads so they sounded like totally new pieces of music."

Those heads have been well and truly flipped.

On his new album, Bonnie Tyler's Holding Out For A Hero becomes a hungry electro-pop anthem, Lana Del Rey's West Coast gets a grungy blues makeover, and Culture Club's Do You Really Want To Hurt Me is injected with a creeping sense of paranoia.

"I learned with Queen that the way to make the songs your own is to stop listening to the original for a little while and discover what it means for you," he says.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The most personal track on the album is Duran Duran's Ordinary World, with Lambert drawn to the lyrical theme "of being an outsider and trying to make your way through everyday normal life".

His atmospheric interpretation aches with the alienation he felt as a child growing up in California.

"When I was a teenager coming to terms with my sexuality, I didn't think I'd have a shot in the music industry, mostly because I was gay," he says.

"We had artists that came out once they had success, Elton John, George Michael, but there was no-one I could compare myself to."

'Full of doubt'

During his stint on American Idol in 2009, Lambert was out to his family and friends, but the show only made veiled references to his sexuality. Even when they did, the tone was questionable: In one episode, Simon Cowell slyly expressed concerns about the singer's "theatricality".

When pictures emerged of him dressed in drag, kissing his ex-boyfriend at a US music festival, it made headlines in the US. Fox News called the photos "embarrassing", and commentators said the fallout cost him the American Idol crown.

"It was stressful and it was confusing," Lambert previously told the BBC. "I was like, 'What am I supposed to do?'"

He emerged from the TV show with a major label record deal but, even then, questions lingered about his commercial viability.

"A lot of people in the industry, even though they were excited for me and wanted to see me, they were full of doubt," he says.

"It was a very interesting time. if I look back at the headlines or the questions I was asked, you wouldn't dare do that today."

Lambert was vindicated when his debut album, For Your Entertainment, went to number one - selling twice as much as Idol victor Kris Allen.

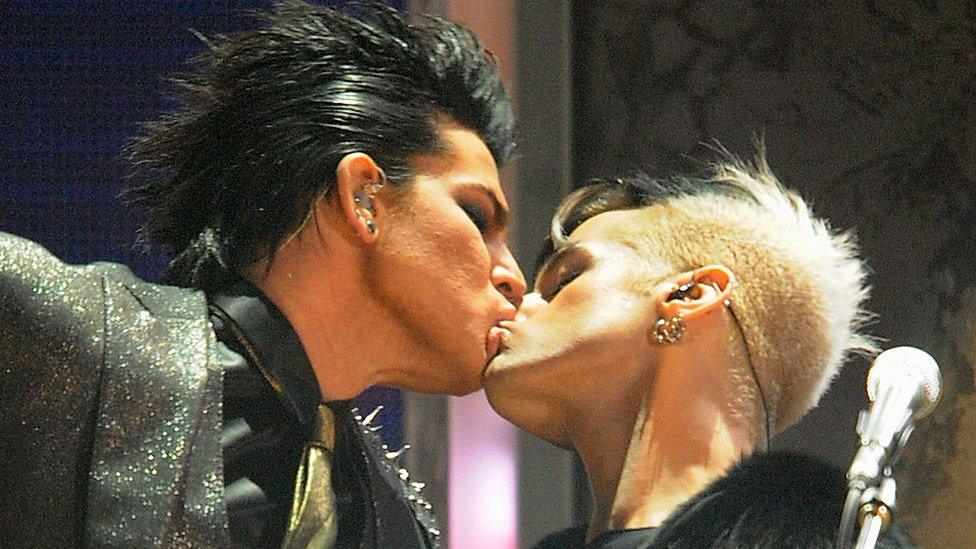

Lambert says this same-sex kiss ended with him being temporarily blacklisted by US TV network ABC

But discrimination doesn't disappear overnight. When Lambert gave his male bassist an impromptu kiss during a 2009 Awards performance, TV network ABC threatened to sue him.

"The network was like, 'How dare you?' They banned me for a while. They threatened me with a lawsuit. It was like, 'Oh, okay, that's where we're at,'" he recalled in an acceptance speech at this year's Sundance film festival.

Since then, he added, "more and more young people" have let him know that his "flamboyant" TV appearances gave them the courage to come out to their parents.

He's worried, however, about the increasingly anti-LGBTQ rhetoric of America's evangelical right, and the rising number of violent attacks on gay bars and drag shows.

When he debuted Ordinary World on US television, external, he dedicated the track to victims of the Colorado Springs tragedy, where a gunman opened fire on an LGBTQ club, killing five and injuring at least 17 others.

Filmed largely in black and white, the performance saw Lambert moving through a haunted, abstract room, filled with faceless mannequins, framing the song as a reverent, melancholy reflection on grief.

"We just wanted to hold their memory in our hearts and not to forget what happened," he says.

"It's not always easy to process these things. I mean, I don't know anybody that was a victim in that tragedy, but I'm still affected by it.

"I remember, right after it happened, I had a conversation with a friend and we were like, 'What would you do in that situation?' And it's a scary thing to have to imagine because it's horrible, but you do now have to think, what would be my plan of action be?

"It affects all of us in the queer community and outside of the queer community."

The singer is due to play London's Koko club on 27 February

Despite Lambert's initial misgivings, the reviews of his covers album have been largely positive. Billboard magazine called it an "impressive journey through Lambert's skillset, external", while Riff magazine highlighted the star's ability to tackle multiple styles and genres.

"It's fascinating to hear Lambert's voice transition from track to track," wrote critic Mike DeWald, external. "More than anything, it's an effective showcase of his dynamic range."

Many reviews highlight one of the album's more obscure covers, I'm a Man.

It was originally released by US glam rocker Jobriath, widely acknowledged as the first openly gay rock star. Launched to great fanfare in 1973, his career came to an unseemly end when, after an unprecedented $80,000 publicity campaign, his debut album was almost totally shunned by the record-buying public.

On tour, he encountered repeated homophobic slurs. After a second album flopped, he was dropped by his record label - re-emerging later as a successful cabaret act, before succumbing to Aids in 1983.

In the intervening years, his music has been reappraised, with musicians including Pet Shop Boys, Def Leppard's Joe Elliot and Jake Shears of Scissor Sisters expressing their admiration.

"He was a sexual hero," Marc Almond wrote in The Guardian in 2012, external. "For all the derision and marginalization he faced, Jobriath did touch lives."

"It's an interesting story about somebody that shot really far for stardom and success, didn't get it, but then found a different version of success later on," says Lambert, who discovered the singer via the 2012 documentary Jobriath AD.

The star has been performing with Queen since 2011, ably stepping into the shoes of the late Freddie Mercury

Like Jobriath, Lambert got his first break in the musical Hair, and he saw many other parallels in their stories.

Ultimately, he realised, that for all the obstacles he's faced, he was lucky to be singing in a more liberal and accepting era.

"It's been proven now that you can be queer and be a mainstream hitmaker," he says.

"It's no longer seen as some kind of niche thing. And I think that's really encouraging for young people."

- Published2 October 2019

- Published21 June 2015