George Alagiah: 'Brilliant, kind' BBC journalist and newsreader dies aged 67

- Published

Watch: A look back at George Alagiah's extraordinary career at the BBC

George Alagiah, one of the BBC's longest-serving and most respected journalists, has died at 67, nine years after being diagnosed with cancer.

A statement from his agent said he "died peacefully today, surrounded by his family and loved ones".

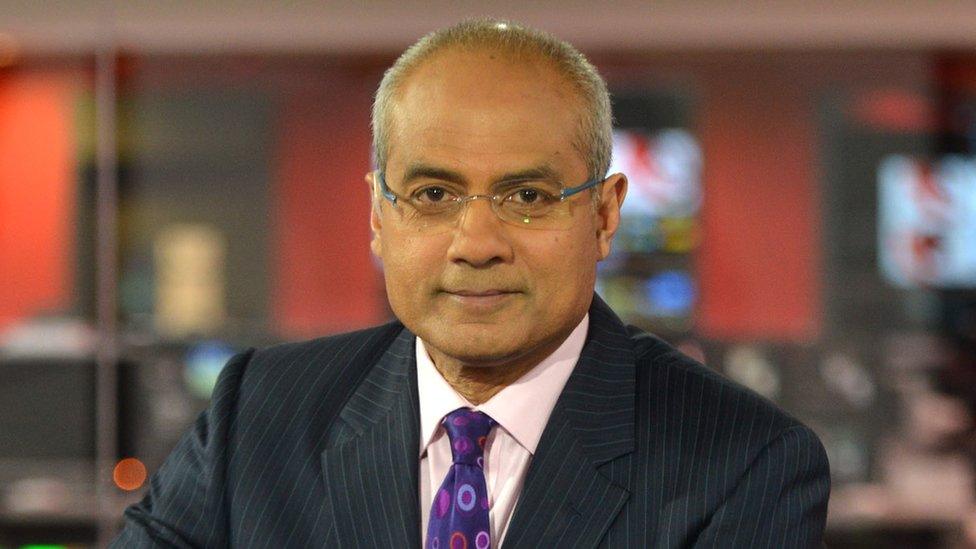

A fixture on British TV news for more than three decades, he presented the BBC News at Six for the past 20 years.

Before that, he was an award-winning foreign correspondent, reporting from countries ranging from Rwanda to Iraq.

He was diagnosed with stage four bowel cancer in 2014 and revealed in October 2022 that it had spread further.

Paying tribute, his agent, Mary Greenham, said: "George was deeply loved by everybody who knew him, whether it was a friend, a colleague or a member of the public.

"He simply was a wonderful human being. My thoughts are with Fran, the boys and his wider family," she said.

Alagiah died earlier on Monday, but "fought until the bitter end", his agent added.

BBC director general Tim Davie said: "Across the BBC, we are all incredibly sad to hear the news about George. We are thinking of his family at this time.

"He was more than just an outstanding journalist, audiences could sense his kindness, empathy and wonderful humanity. He was loved by all and we will miss him enormously."

BBC World Affairs editor John Simpson tweeted, external: "A gentler, kinder, more insightful and braver friend and colleague it would be hard to find."

BBC chief international correspondent Lyse Doucet called him "a great broadcaster", a "kind colleague" and "a thoughtful journalist".

Clive Myrie, presenting the BBC News at One, said: "On a personal note, George touched all of us here in the newsroom, with his kindness and generosity, his warmth and good humour. We loved him here at BBC News, and I loved him as a mentor, colleague and friend."

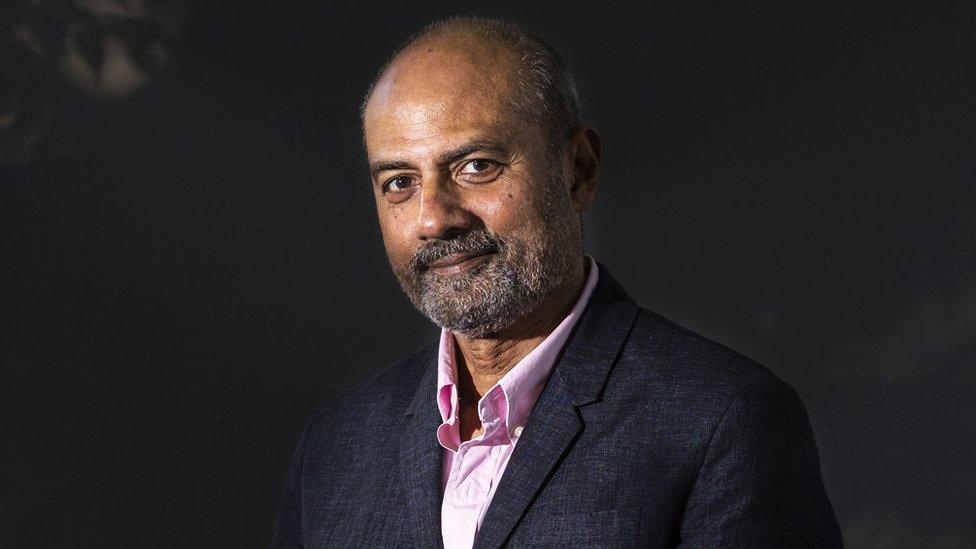

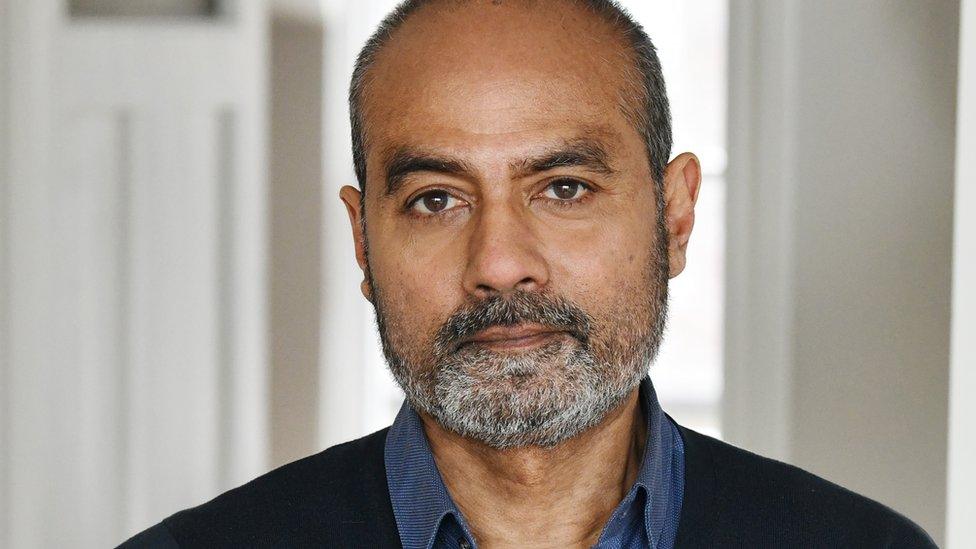

George Alagiah was a fixture on British TV news for more than three decades

Fellow journalists including LBC's Sangita Myska, the Guardian's Pippa Crerar and Mark Austin of Sky News were among those to also pay tribute.

Austin tweeted: "This breaks my heart. A good man, a rival on the foreign correspondent beat but above all a friend. If good journalism is about empathy, and it often is, George Alagiah had it in spades."

Myska noted Alagiah's influence on British Asian reporters.

"Growing up, when the BBC's George Alagiah was on TV my dad would shout "George is on!". We'd run to watch the man who inspired a generation of British Asian journalists. That scene was replicated across the UK. We thank you, George. RIP xx"

Former BBC North American editor Jon Sopel wrote, external: "Tributes will rightly be paid to a fantastic journalist and brilliant broadcaster - but George was the most decent, principled, kindest, most honourable man I have ever worked with. What a loss."

BBC security correspondent Frank Gardner recalled Alagiah visiting him in hospital after he was shot and critically injured in an al-Qaeda attack in Saudia Arabia in 2004.

"He brought me his book A Passage to Africa, and we talked for hours about the continent he loved and spent so much of his career covering. A true journalist and a great author."

George Alagiah remembered

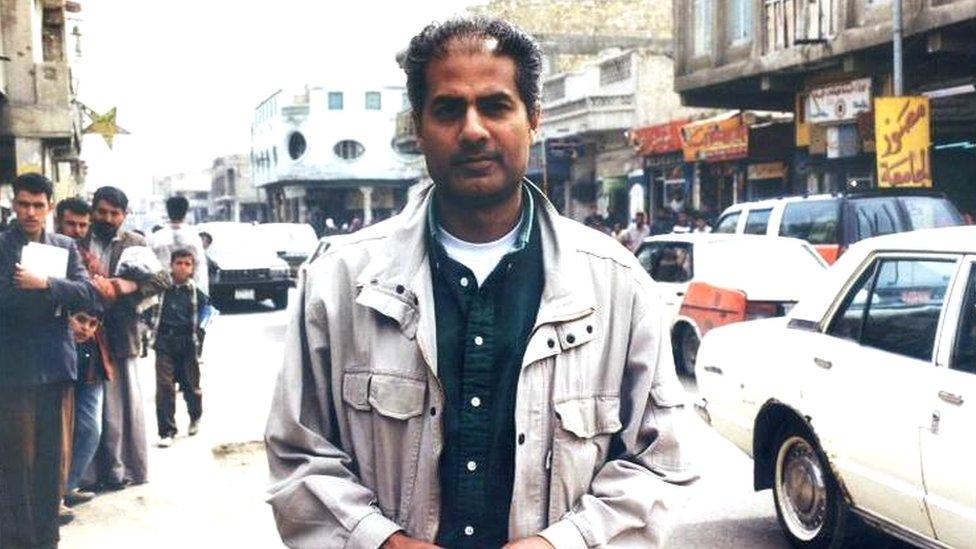

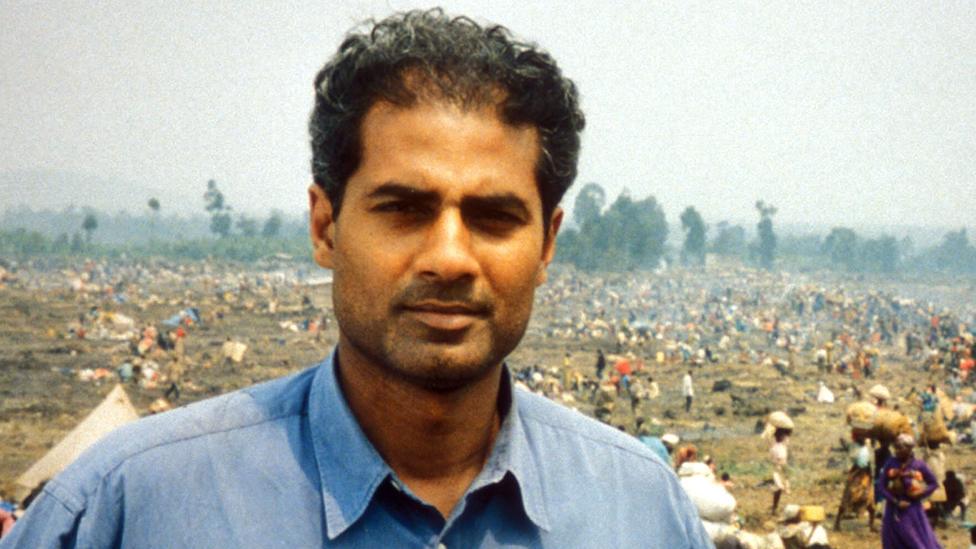

Alagiah won awards for reports on the famine and war in Somalia in the early 1990s, and was nominated for a Bafta in 1994 for covering Saddam Hussein's genocidal campaign against the Kurds of northern Iraq.

He was also named Amnesty International's journalist of the year in 1994, for reporting on the civil war in Burundi, and was the first BBC journalist to report on the genocide in Rwanda.

He is pictured here working as a foreign correspondent in Baghdad

George Maxwell Alagiah was born in Colombo, Sri Lanka, before moving to Ghana and then England in childhood.

His main childhood memory of Sri Lanka was leaving it. His parents were Christian Tamils; the country, then called Ceylon, mired in ethnic violence.

His father, Donald, was an engineer specialising in water distribution and irrigation. Feeling unwelcome and unsafe in his own land, he took his young family to Africa in search of a new and better life.

The family initially prospered in Ghana but Alagiah's parents decided to educate their children in England. At the age of 11, his father dropped him off at boarding school in Portsmouth; they both had to hold back the tears.

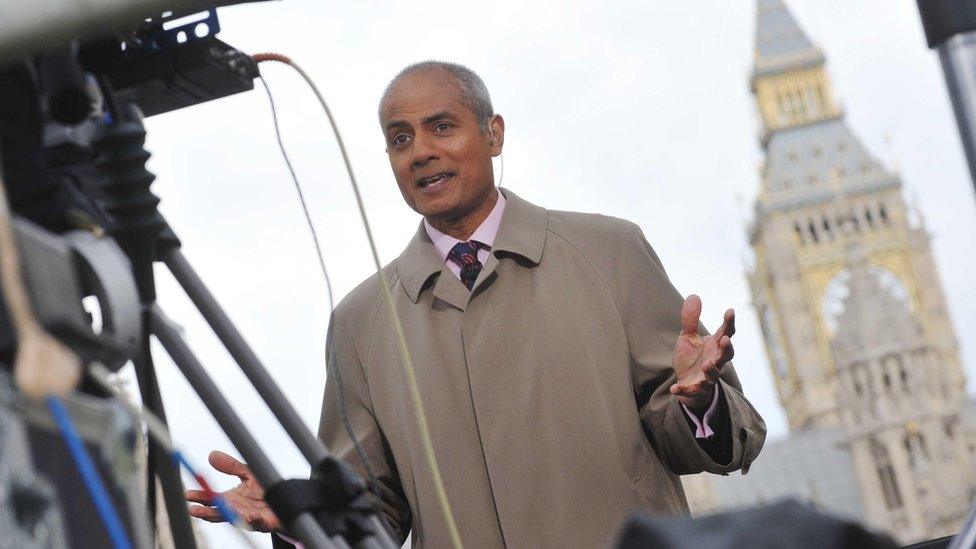

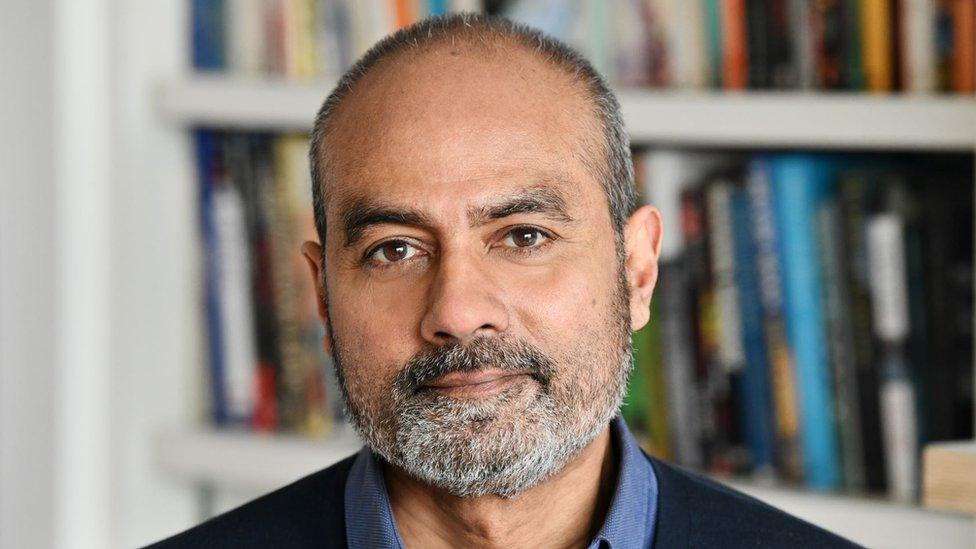

Reporting from outside the Houses of Parliament the day after the 2010 general election

His childhood of change and assimilation helped shape his personality and informed his professional judgement.

There was some racism. He was almost the only boy of colour; there were "Bongo Bongo land" taunts in the showers. He gave up asking people to say his name correctly (his family pronounced it, "Uller-hiya").

"In those days," he reflected "you were almost apologetic if you had a 'funny name'." The alternative was to stick out like an "exotic cactus in a bed of spring meadow plants".

But, in some ways, his school in England - St John's College - was a closed and unreal society, which sealed him off from the huge social changes going on outside its walls. The anti-immigrant sentiment in many parts of the country was something that largely passed him by.

As he grew up, he became, he believed, the "right sort" of foreigner in a land where "class trumps race every time".

Later, he attended Durham University, where he met, and later married, Frances Robathan.

After graduating, he spent seven years at South Magazine, proud of its editorial line which painted an unequal world as an unstable one.

He joined the BBC as a foreign affairs correspondent in 1989 and then became Africa correspondent, the continent of his childhood.

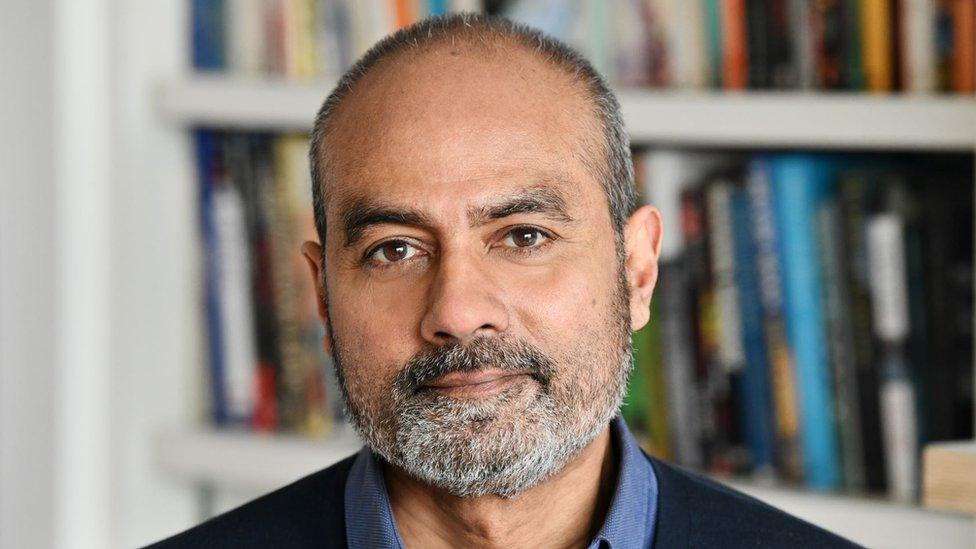

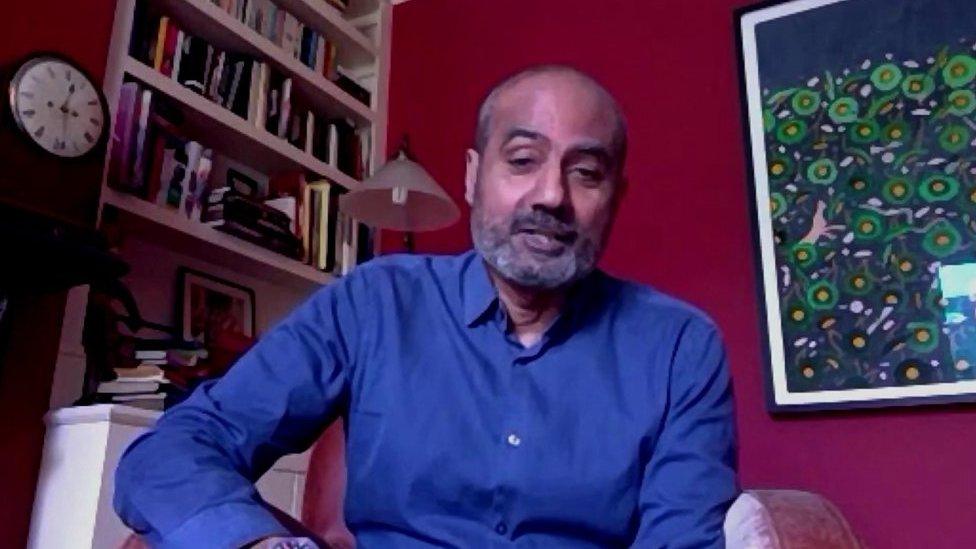

George Alagiah, pictured in July of last year

It was often a depressing experience. He interviewed child soldiers in Liberia, victims of mass rape in Uganda and witnessed hunger and disease almost everywhere.

"There is a new generation in Africa", he wrote, "my generation, freedom's children, born and educated in those years of euphoria after independence, we have had a chance. We didn't do much with it."

One of his proudest professional moments came when he broadcast some of the first pictures of the ethnic cleansing in Kosovo in 1999, he said.

Other stories he covered in news reports and documentaries included the trade in human organs in India, street children in Brazil, civil war in Afghanistan and human rights violations in Ethiopia.

He interviewed figures including South African President Nelson Mandela, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, UN Secretary General Kofi Annan and President Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe.

Moving to news presenting, he fronted the BBC One O'Clock News, Nine O'Clock News and BBC Four News, before being made one of the main presenters of the Six O'Clock News in 2003.

He anchored news programmes from Sri Lanka following the December 2004 tsunami, as well as reporting from New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, and from Pakistan following the South Asian earthquake in 2005.

He was appointed an OBE for services to journalism in 2008.

'Energised and motivated'

After Alagiah's initial cancer diagnosis in 2014, the disease spread to his liver and lymph nodes, which needed chemotherapy and several operations, including one to remove most of his liver.

He said he was a "richer person" for the experience upon returning to presenting in 2015, and said working in the newsroom was "such an important part of keeping energised and motivated".

He had to take several further breaks from work to have treatment, and in January 2022 said he thought the cancer would "probably get me in the end", but that he still felt "very lucky".

Speaking on the Desperately Seeking Wisdom podcast in 2022, he said that when his cancer was first discovered, it took a while for him to understand what he "needed to do".

"I had to stop and say, 'Hang on a minute. If the full stop came now, would my life have been a failure?'

"And actually, when I look back and I looked at my journey... the family I had, the opportunities my family had, the great good fortune to bump into [Frances Robathan], who's now been my wife and lover for all these years, the kids that we brought up... it didn't feel like a failure."

Alagiah had two children with Frances.

What are bowel cancer symptoms?

A persistent change in bowel habit - going more often, with looser stools and sometimes tummy pain

Blood in the stools without other symptoms, such as piles

Abdominal pain, discomfort or bloating always brought on by eating - sometimes resulting in a reduction in the amount of food eaten and weight loss

Most people with these symptoms do not have bowel cancer, but the NHS advice is to see your GP if you have one or more of the symptoms and they have persisted for more than four weeks.

And if you, or someone you know, have been affected by cancer, information and support is available on the BBC's Action Line page.

Related topics

- Published24 July 2023

- Published24 July 2023

- Published12 October 2022

- Published3 January 2022

- Published18 October 2021

- Published31 March 2020

- Published24 January 2019