Picasso’s twisted beauty – and the ‘trail of female carnage’ he left behind

- Published

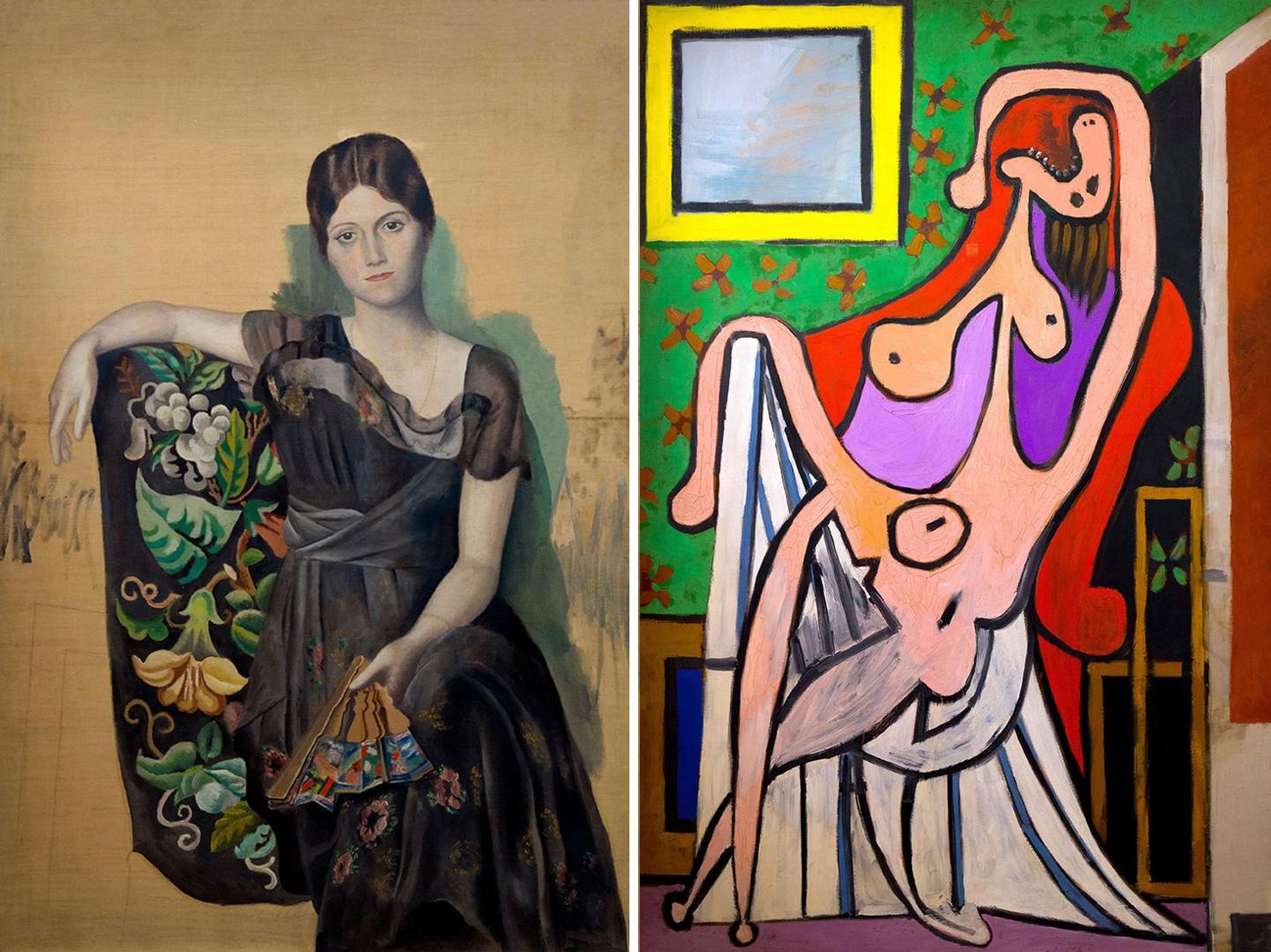

Paintings of Picasso's wife Olga Khokhlova. The first from 1918, at the start of their relationship and the second from 1929 as the relationship broke down

What do you see when you look at the two paintings above - a beautiful woman on the left and a monstrous beast on the right?

They are both of a woman sitting in an armchair. Her likeness is realistic in the first painting. She clutches a fan in her hand and gazes pensively, lost in thought, serene, yet tinged with sadness.

In the second painting, her body and features are twisted. It's hard to tell which limb is which. Her head is flung back and she bares her sharp teeth.

"She's like some kind of strange creature of prey," says art critic Louisa Buck.

They are such a contrast and yet both paintings are depictions of the same woman, Pablo Picasso's first wife, Olga Khokhlova, a Ukrainian ballerina who danced with the Ballets Russes.

Picasso stands in front of the portrait he created of his wife Olga Khokhlova

But 50 years on from his death, is it possible to define Picasso as the beauty or the beast, just as he might have been trying to do in the paintings of Ms Khokhlova?

The artist once said: "I paint the way some people write an autobiography."

The women in his life were catalysts for Picasso's work, Ms Buck explains. But during the course of his artistic life she says he "left a trail of female carnage in his wake".

"His first great love, Fernande Olivier, was left almost destitute. His wife Olga became very unstable and Marie-Thérèse Walter [his mistress] committed suicide after he died," she says.

His attitudes towards women were problematic, but also have to be considered from the perspective of his upbringing, the critic explains.

"He grew up in late 19th Century Andalusia in a macho, patriarchal environment, where he was going to prostitutes when he was in his early teens - this was commonplace and deemed to be acceptable," she said.

Comparing the painting with this photograph shows how realistic the portrait is of Olga Khokhlova

Picasso and Ms Khokhlova met in 1917, when he was asked to create the designs for a then-radical ballet.

She was 26 and Picasso 10 years older. They married in 1918, lived together in Paris and had a son in 1921.

The painting of her at the top of this article was completed in 1918.

"It looks slightly unfinished," says Ms Buck. "You've got these brushstrokes in the background, and her face itself is quite mask-like as well. It's quite inscrutable."

Ms Buck explains that Ms Khokhlova's backstory helps with the interpretation of the work, which contains a lot of poignancy.

"She was caught up with the fate of members of her close family, who were in Russia at the time of the Revolution. She couldn't make contact with them," she says.

Woman with Pears, 1909, is a portrait of Picasso's first love, Fernande Olivier, in the Cubist style

The critic questions whether Picasso is looking at his wife and sympathising with her sadness as he paints her. She also suggests he might have painted it to please and honour her, as she had conventional taste in terms of art.

Prior to the painting, Picasso had become famous as one of the founders of Cubism, a style of art in which the subject or object in the painting appears fragmented into geometric forms.

But he was continually restless and wanted to reinvent himself, says Ms Buck, with the more realistic 1918 work of Ms Khokhlova possibly painted to prove he wasn't going to be pigeonholed into one particular style.

That restlessness presented itself in his personal relationships too.

Fast forward to 1929, and the second painting of Ms Khokhlova - below, and on the right at the top of the article - is much more hostile.

"The way that Picasso depicts a woman over the course of their relationship changes," says Michael Cary, curator at Gagosian Gallery in New York. "When you look at the portraits of Olga, she starts off as the beautiful wife and by the end of their relationship, she's depicted as a hag and a monster and it's hard to see love in their relationship in the work."

In 1927, Picasso had met his mistress, Marie-Thérèse Walter and the relationship with his wife had begun to break down.

It had "all the cliched attributes of a mid-life crisis," says Ms Buck.

Ms Walter was a 17-year-old schoolgirl and Picasso was 30 years older. "Times have changed, but even then it was a big age gap."

Large Nude in a Red Armchair, 1929, a painting of Picasso's first wife, Olga Khokhlova, as their marriage deteriorated

This second painting of Ms Khokhlova may express her emotional anguish at the breakdown of the relationship, but also Picasso's frustration with her, says Ms Buck.

"He's distorted her body, the way he's pulled it and pushed it and put it in different directions.

"He's angry with the fact that she's thwarting him in a way by not just going off quietly into the sunset."

In the more realistic 1918 painting of Ms Khokhlova the colours are muted - says Ms Buck - but the red of the armchair in the painting next to it is a more violent, dangerous colour, the red of flesh and blood.

"Don't forget Picasso grew up watching bull fights, watching conflict," she explains. Looking at the blank mirror, or window, in the background, you can't see any way out and there is no perspective or reflection, says Ms Buck.

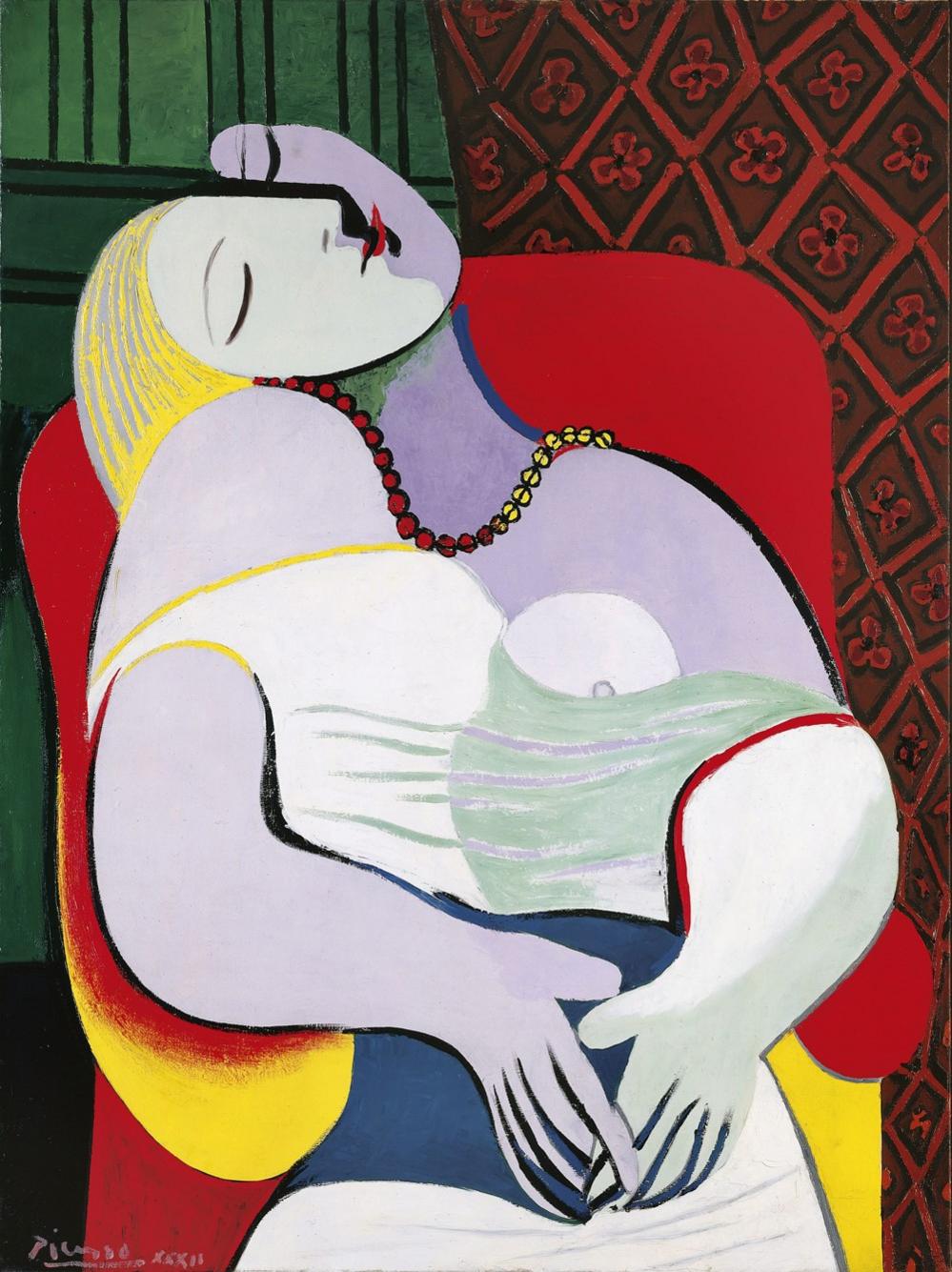

When Le Rêve, 1932, a painting of Marie-Thérèse Walter was first exhibited some people turned their heads away in shock

Ms Khokhlova and Picasso eventually separated in 1935 when Ms Walter was pregnant, but Ms Khokhlova refused to divorce. She remained married to him until her death in 1955.

It must have been painful for Ms Khokhlova to see Ms Walter's impact on his creativity, says Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, the grandson of Ms Khokhlova and Picasso.

After he phased out Ms Walter from his life he went on to have relationships with - and paint - his other lovers, including Dora Maar, Françoise Gilot and his second wife Jacqueline Roque, who took her own life after his death.

When he died in 1973, he was revered as a "superstar", says Ms Buck. By the end of his life, he had become adept at manipulating his own image and mythologising himself, she says. Images of Picasso wearing a black and white striped T-shirt with a piercing strong gaze became synonymous with his brand.

"Picasso is a man of contradictions," says Diana Widmaier-Picasso, the granddaughter of Picasso and Ms Walter. "He can be tender, he can be cruel."

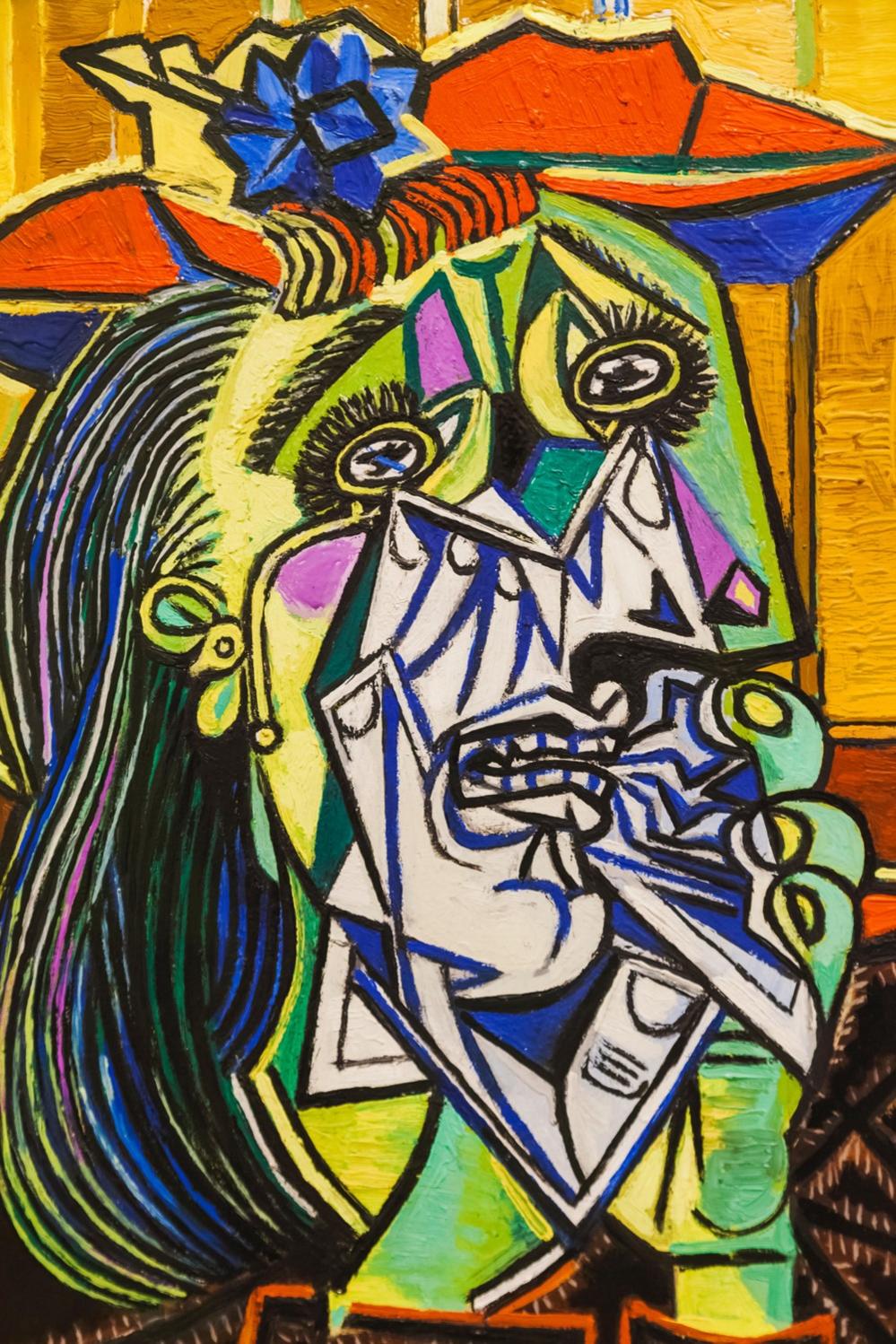

Weeping Woman, 1937, thought to be a depiction of Picasso's lover, Dora Maar, and her sorrow at the Spanish Civil War

His cruelty could be seen in the treatment of his relationship with his first love, Fernande Olivier, says Alexandra Schwartz, writer at The New Yorker magazine. Picasso had strong moods, she says.

"In love, he's wonderful, but when he's irked, when he gets angry, it's not so terrific," says Ms Schwartz. He wanted exclusive access to Ms Olivier, she says, even when he was not there, and so locked the door to their apartment from the outside, keeping her a prisoner in their studio.

This is totally unacceptable by today's standards, says psychotherapist Philippa Perry, but at that time women were treated like possessions.

"Like you can control paint on a canvas, he wanted to control his world like that and control other people in it like that," she says.

Ms Buck says she is not condoning his behaviour, but she would argue that "in all its complexity, all its problematic, all its unpleasant sides, it's great art, and actually, partly why it's great art is because it carries all these problems and contradictions within it".

"I don't think you can cancel Picasso," she says.

Just as the two paintings of Ms Khokhlova are open to many interpretations, the artist is also highly complicated. As Paloma Picasso, the daughter he shared with Ms Gilot, says about her father.

"You can't just say he's a monster or he's a genius - he's just a man."

Picasso: The Beauty and the Beast is on Thursdays, 21:00 on BBC Two, or watch on BBC iPlayer.