Napoleon's Ridley Scott on critics and cinema 'bum ache'

- Published

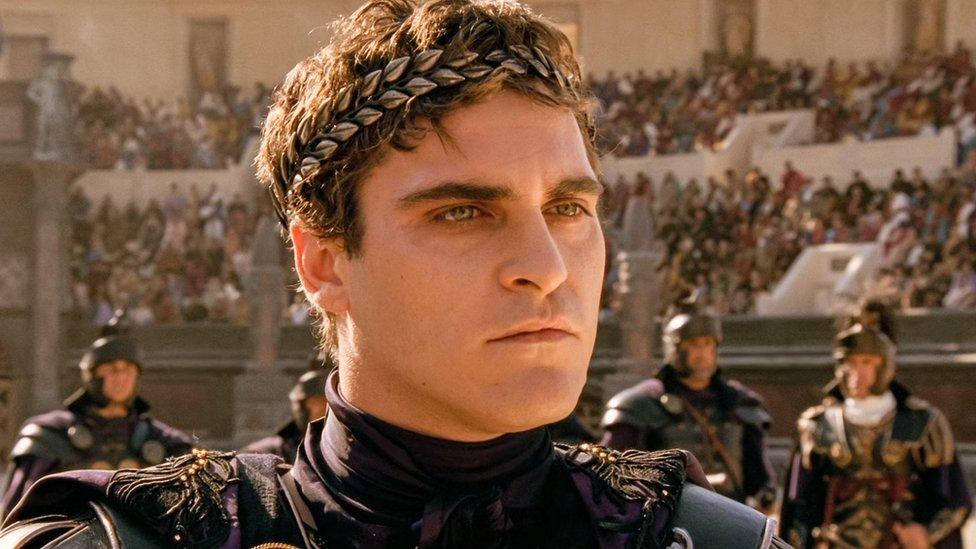

Joaquin Phoenix as the ruthless Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte

Sir Ridley Scott is famously forthright.

The director of celebrated films including Gladiator, Alien, Thelma & Louise and Blade Runner certainly speaks his mind.

Does he seek out advice? Asking someone what they think is a "disaster", he tells me.

What about his lack of a best director Oscar - despite being at the helm of some of the most memorable films of the past four decades?

"I don't really care."

And as for the historians who have suggested his latest movie, Napoleon, is factually inaccurate: "You really want me to answer that?... it will have a bleep in it."

We meet in a plush hotel in central London.

Scott had recently arrived from Paris, where the movie - which stars Joaquin Phoenix as the French soldier turned emperor, and Vanessa Kirby as his wife (and obsession) Josephine - had its world premiere.

Sir Ridley (with Phoenix and Kirby) at the Paris world premiere

It's a visual spectacle that contrasts the intimacy of the couple's relationship with the actions of a man whose lust for power brought about the deaths of an estimated three million soldiers and civilians.

"He's so fascinating. Revered, hated, loved… more famous than any man or leader or politician in history. How could you not want to go there?"

The film is two hours and 38 minutes long. Scott says if a movie is longer than three hours, you get the "bum ache factor" around two hours in, which is something he constantly watches for when he's editing.

"When you start to go 'oh my God' and then you say 'Christ, we can't eat for another hour', it's too long."

In spite of the "bum ache" issue, it's been reported that he plans a longer, final director's cut for Apple TV+ when the movie hits the streamer, but "we're not allowed to talk about that".

Scott looked to Jacques-Louis David's painting, Napoleon Crossing the Alps

Napoleon has been well reviewed in many parts of the UK media. Five stars in the Guardian, external for "an outrageously enjoyable cavalry charge of a movie". Four stars in The Times, external for this "spectacular historical epic" and in Empire for "Scott's entertaining and plausible interpretation of Napoleon".

The French critics have been less positive.

Le Figaro said the film could be renamed "Barbie and Ken under the Empire". French GQ said there was something "deeply clumsy, unnatural and unintentionally funny" in seeing French soldiers in 1793 shouting "Vive La France" with American accents.

And a biographer of Napoleon, Patrice Gueniffey in Le Point magazine, attacked the film as a "very anti-French and very pro-British" rewrite of history.

"The French don't even like themselves" Scott retorts. "The audience that I showed it to in Paris, they loved it."

In his movie, Napoleon's empire-building land grabs are distilled into six vast battle scenes.

One of the emperor's greatest victories, at Austerlitz in 1805, sees the Russian army lured onto an icy lake (shot at "an airfield just outside London") before the cannons are turned on them.

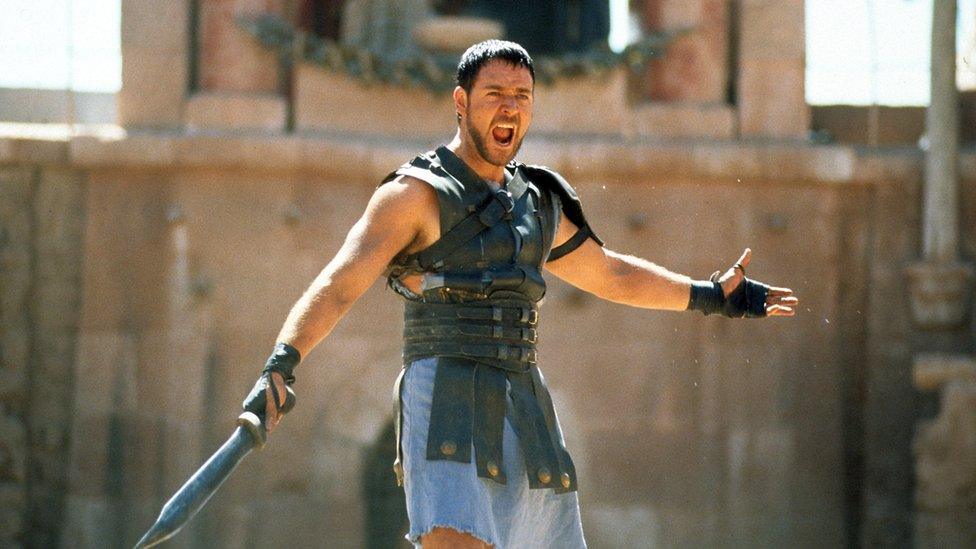

"The reverse angle in the trees was where I made Gladiator… I managed to blend them digitally so you get the scale and the scope".

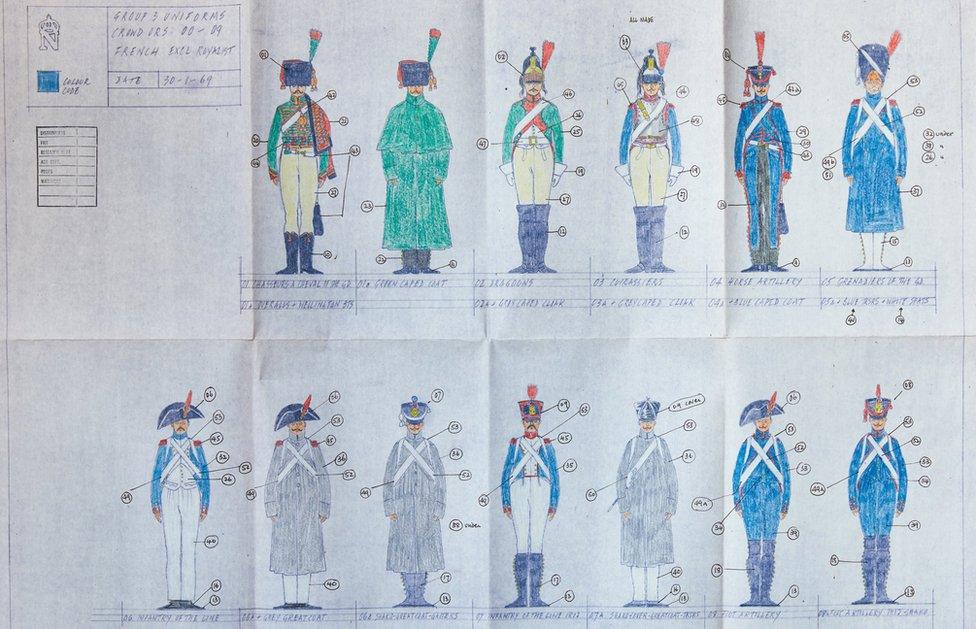

To prepare for battles scenes, Scott gave images which he had storyboarded to his crafts team

As the cannonballs hurtle into the ice, bloodied soldiers and horses are sucked into the freezing waters, desperately trying to escape.

It's dramatic. It's terrifying. It is also beautiful.

"I'm blessed with a good eye, that's my strongest asset," says South Shields-born Sir Ridley, who went to art school first in Hartlepool and then London.

In the 1970s he was one of the UK's most renowned commercial directors, making, he tells me, two adverts a week in his heyday.

He always wanted to direct films but "I was too embarrassed to discuss it with anyone", and "I didn't know how to get in."

Once he did, he rose fast.

Scott's visual artistry makes him a consummate creator of worlds, whether that's outer space in Alien and The Martian, civil war Somalia in Black Hawk Down, medieval England in Robin Hood or the Roman Empire in Gladiator.

Scott's 1979 science fiction horror film, Alien, was considered "culturally significant" by the US Library of Congress

An accomplished artist, he does his own storyboarding.

"You could publish them as comic strips," he says. "A lot of people can't translate what's on paper to what it's going to be and that's my job."

His Napoleon, Joaquin Phoenix, tells me Scott also "draws pictures, as he's coming to work, of what the scene is."

He finds Scott an open and receptive director. "He's figured everything out and yet he's also able to spontaneously pivot" when new ideas are suggested, on this occasion even when there were 500 extras, a huge crew and multiple cannons.

Phoenix was "excited" to work with Scott again, 23 years after he was cast as the emperor Commodus in Gladiator.

"The studio did not want me for Gladiator. In fact, Ridley was given an ultimatum and he fought for me and it was just this extraordinary experience."

Joaquin Phoenix said Sir Ridley "fought" with the studio for him to take on the role of Commodus in Gladiator

Scott has called Phoenix "probably the most special, thoughtful actor" he has ever worked with.

The leading actors had freedom to develop the relationship between Napoleon and Josephine, a woman six years older than him, who he divorced because she was unable to provide him with an heir, but whose name was on his lips when he died in exile on St Helena. "France, the Army, the Head of the Army, Josephine" were the Emperor's last words.

Vanessa Kirby says of her experience being directed by Scott that "none of it was prescriptive from the start and I thought that was really freeing."

Vanessa Kirby says it was freeing to see the relationship between Josephine and Napoleon as "unconventional"

But she adds that she had to adjust to the pace at which he works.

"He moves really fast. You might have five big scenes in one day, which means you're on the fly."

They shot Napoleon in just 61 days. "If you know anything about movies, that should have been 120," Scott tells me.

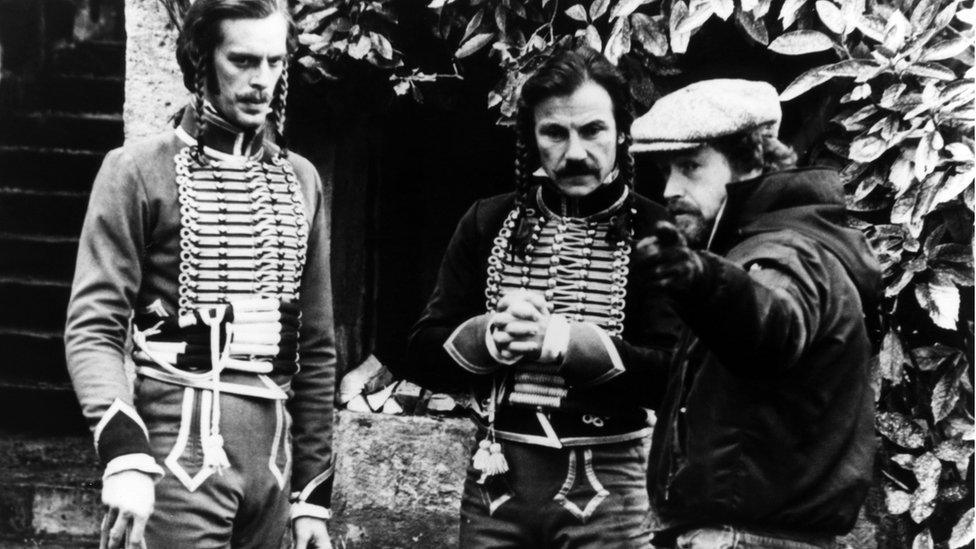

In the early days, he used to operate the camera on his films as well as direct - think The Duellists, Alien, Thelma & Louise, though it wasn't allowed on Blade Runner.

He says he realised where the real power lay - with the camera operator and the first AD - and didn't want to relinquish it.

Scott's fascination with Napoleon goes back to his first film, 1977's The Duellists, set during the Napoleonic Wars

On Napoleon he worked with up to 11 cameras at the same time and directed them from an air conditioned trailer, saying: "It's 180 degrees outside and I'm sitting inside shouting 'faster!'."

Using all those cameras shooting from different angles "frees the actor to come off-piste and improvise" because you don't need to repeat endless takes (which is "disastrous").

Immortalising Napoleon on film was something Scott's hero Stanley Kubrick tried and failed to do. "He couldn't get it going, surprisingly, because I thought he could get anything going." That was down to money, says Scott.

These costume designs were for Stanley Kubrick's meticulously researched, but unmade film about Napoleon

His Napoleon watches Marie Antoinette die at the guillotine and fires a cannonball at the Sphinx. The artistic licence in this impressionistic film has put up the backs of some historians.

Scott says 10,400 books have been written about Napoleon, "that's one every week since he died".

His question, he tells me, to the critics who say the film isn't historically accurate is: "Were you there? Oh you weren't there. Then how do you know?"

Director of photography Dariusz Wolski said Jacques-Louis David's coronation painting was an influence

The moment Napoleon crowns his wife Josephine (Vanessa Kirby) Empress

Scott announced he was making Napoleon on the day he wrapped his previous film, The Last Duel, which starred Jodie Comer.

She was originally cast as his Josephine, but had to pull out after the dates were pushed back by the pandemic.

With Napoleon heading into cinemas, Scott is about to restart filming Gladiator 2, with Paul Mescal and Denzel Washington, a shoot interrupted by the actors' strike.

So why go back to Gladiator? "Why not, are you kidding?"

He also has another movie in the pipeline which is already written and cast, but what it is, "I'm not going to tell you."

And he will celebrate his 86th birthday later this month.

Many might be happy to slow down, but not Scott. He will make films for the rest of his days, he tells me.

"I go from here to Malta, I shoot in Malta, finish there and I've already recce'd what I'm doing next."

So would he have any advice for his younger self?

"No advice. I did pretty good. I got there," comes his characteristically direct reply.

Related topics

- Published2 November 2018

- Published30 November 2021

- Published31 January 2018

- Published29 November 2017