Benjamin Zephaniah on racism, refusing an OBE and football

- Published

Watch: Benjamin Zephaniah in his own words, as other poets pay tribute to his legacy

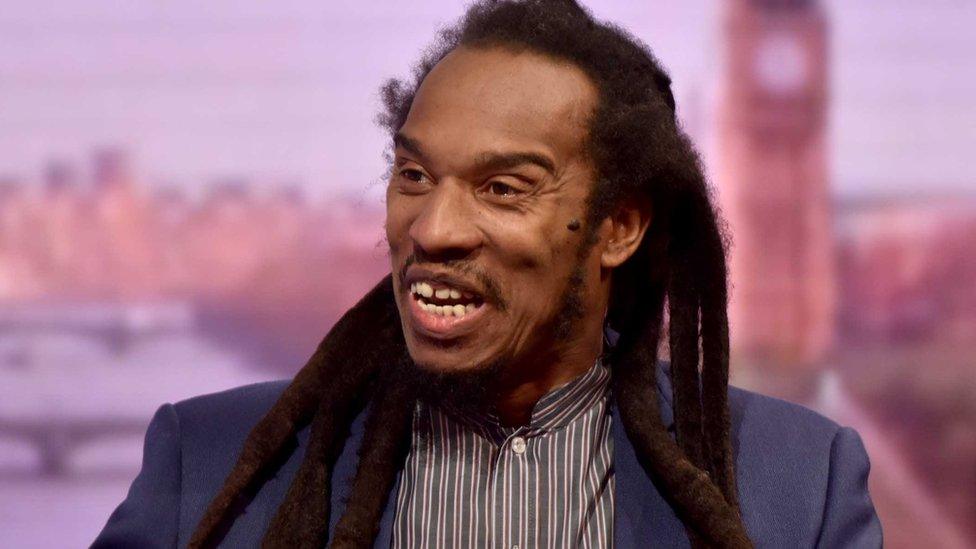

Benjamin Zephaniah was a man of words - he was profound, prolific and never shied away from what really mattered to him.

Words flowed out of him, whether written, spoken or sung.

"In the beginning was the word, and the word became poetry, and I discovered it and found that it was great," he said in his autobiography, an echo of the start of the gospel of John.

Zephaniah, who died on Thursday at the age of 65, had many missions in life - some were political and some were personal.

But from his troubled childhood onwards, he found power in communicating.

Despite leaving school aged 13 without being able to read or write, within two years he'd made a name for himself in dub poetry - performance poetry that originated in Jamaica.

His love of creativity was clear, but he later said he "went off the rails", external and was jailed for burglary in his late teens.

In 1979, aged 22, he decided to start afresh by moving from Birmingham to London, where he "met other creative types".

His first poetry book, Pen Rhythm, was published in 1980, and was the start of a long and celebrated career, external.

Here he is, in his own words, on just some of the things he felt passionately about.

Poetry

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

"I wanted to change the image of poetry," he told the Guardian, external. "I wanted to bring it to life and talk about now and what was happening to us."

He also said, external: "Even doing interviews I struggle for the words, but when I'm doing poetry I have this licence.

"I can change the words, leave a bit to your imagination, I can be as raw as I want to be.

"My mum always says when I'm on stage, 'That's when I see my son'."

In his poem Pencil Me In, he wrote:

"Every pencil needs a hand,

"And every mind needs to expand,

"I know a pencil,

"Poetry

"is me and it, in harmony."

Childhood and family

Zephaniah grew up with his parents and seven brothers and sisters in Birmingham.

Speaking about his father, he told BBC Radio 4's Desert Island Discs in 1997: "He beat me, and I can remember, obviously, some of the beatings.

"But most of all I remember him beating her [his mother]. He passed away not too long ago.

"And it's a real bit of a sore point in my family at the moment, because my mother ran away from him with me, leaving her other children with him.

"So when he passed away, the other children saw him as a kind of hero, a lone man who raised all these children on his own.

"And all my memories of him was having almost like a wanted poster in my mind, a fixed picture of him. This is the face I've got to avoid."

In 2009, he told the Guardian, external: "It's sad, but what has brought us more together was my cousin dying in police custody in 2002.

"It was something I used to rant on about and then - bang - it happened to us. I think my family now understand more why I talk about what I talk about."

Zephaniah visited Chenjiagou primary school in China in 2012

Zephaniah's relationship with his mother remained steadfast.

"I am very close to my mother and I talk to her every day," he said.

"She has gone through so much. As a nurse she had to tend to people who were racists and she always tries to see the good in people. I am like that too. I am fascinated with why people believe what they believe."

But a great sadness in his life was not being able to have children. "I used to find that tough," he said. "There were lots of years of trying and tests, but now I am easy with it. That's life.

"I get at least 40 letters a week from children saying, 'I love your poetry, Benjamin,' or 'I am reading your book.'"

Racism

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

"Black people are not slaves. They are human beings who were turned into slaves," he told Lacuna Magazine, external.

He said his first racist attack, external was "was a brick in the back of the head" as a child, leaving him on the ground with blood pouring from his head. A boy hit him as he rode past on his bicycle - he was told to "go home".

Zephaniah spoke out against racism throughout his life.

In this extract from his 1999 poem What Stephen Lawrence Has Taught Us, external, he wrote about the murder of the 18-year-old in a racist attack by a gang of young white men in south-east London. Two men were eventually convicted in 2012. Other suspects have never been convicted.

"It is now an open secret

"Black people do not have

"Chips on their shoulders,

"They just have injustice on their backs

"And justice on their minds,

"And now we know that the road to liberty

"is as long as the road from slavery."

Turning down an OBE

In 2003 he turned down becoming an Officer of the Order of the British Empire, external.

"Me? I thought, OBE me? Up yours, I thought," he wrote in the Guardian.

"I get angry when I hear that word 'empire'; it reminds me of slavery, it reminds of thousands of years of brutality, it reminds me of how my foremothers were raped and my forefathers brutalised.

"It is because of this idea of empire that black people like myself don't even know our true names or our true historical culture."

Being a sportsman

A lifelong Aston Villa fan, he told the Guardian in 2020, external that aged 62 he was still playing 11-a-side football with an under-30s team.

"They cannot believe how fast I can run," he said. "I'm still a good sprinter and a reasonably good dribbler."

Although he loved running and was captain of the under-13s team at county level, he told the newspaper why he stopped racing as a child.

"We went to a race against southern European countries and on the way there they were telling me, 'You'll never be English.' I was captain of the team and we won, and they gave me the flag to drape myself in and I couldn't do it."

Being dyslexic

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Zephaniah found out he was dyslexic aged 21, at an adult education class in London, where he learned to learn to read and write.

"I always tell people with dyslexia, especially children, that it's not a mark of your intelligence.

"You can be full of stories - you just have to find a way of telling them. And now we have lots of technology and teachers, professors at university that are aware of dyslexia and can help. So dyslexia shouldn't hold you back.

"We now know that some of the brainiest people around have or had dyslexia, including Einstein!" he told BookTrust in 2020, external.

The power of connection

For Zephaniah, belonging and feeling connected with other people meant everything to him.

The trick was to find the right people, though.

"We all need gangs. We're social animals. The key is finding the people that are doing good stuff instead of doing bad stuff," he said.

He loved the "deep connection" he had with people attending his live shows.

"The thing that has touched me more than anything is the stories people have shared with me," he wrote on his website, external.

Being nice

Zephaniah was a regular visitor to Leicester's De Montford University, where he was given an honorary degree

Keen to challenge perceptions, he told Lacuna Magazine: "What do I do as a black man in England? I try my best to counter the stereotype.

"For those people who fear black men, I want to be the nicest guy they've ever met."

Hope

He was also an optimist.

"Well I can't prove it, but I just believe in the triumph of good over evil. You've got to be hopeful," he told the Guardian in 2020, external.

"One of the things our oppressors hate is when they try to hold us down and - it's Maya Angelou - still I rise. You try to hold me down, but I'll keep coming back."

Faith

Zephaniah had a spiritual side, saying: "I think religion has given God a bad name.

"When I say 'faith', I'm talking about a belief, for want of a better word - I think I have a better word: a knowledge of God - that I get through meditation, which doesn't need anybody else: doesn't need the church, doesn't need a priest, doesn't need an imam, doesn't need anything.

"Just learn to meditate!" he told High Profiles in 2005, external.

Veganism

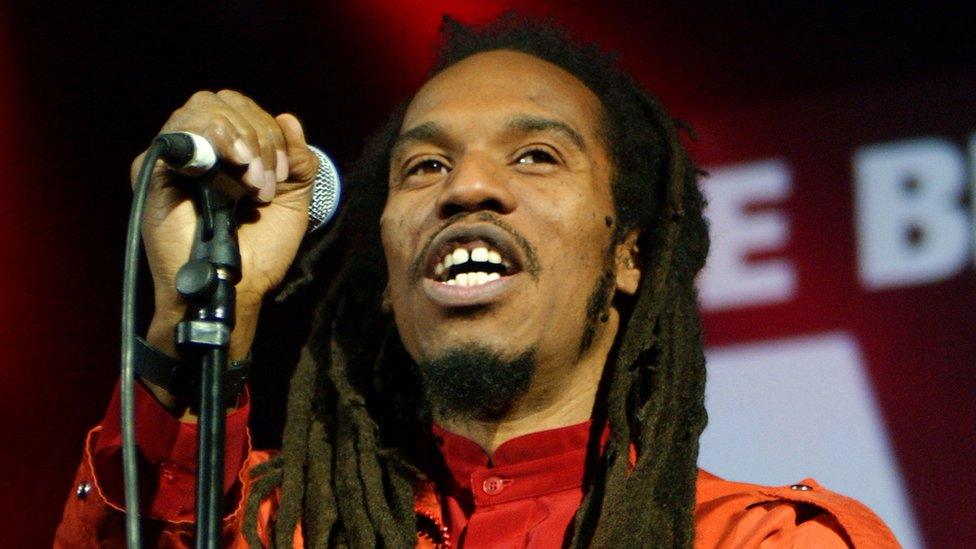

Zephaniah performed with his band The Revolutionary Minds, at the Vegan Camp Out festival in 2021

Zephaniah was an animal rights activist and ambassador for the Vegan Society, having decided to stop eating animals aged nine.

His poem Talking Turkeys, external says:

"Be nice to yu turkeys dis Christmas,

"Don't eat it, keep it alive,

"It could be yu mate, an not on your plate

"Say, Yo! Turkey I'm on your side."

He wrote in his autobiography, The Life and Rhymes of Benjamin Zephaniah, about his allotment: "A lot of organic gardening is trial and error but I love, it, even though it takes time.

"I hardly ever go to a supermarket. And I listen to Gardeners' Question Time more than you might imagine."

Making a difference

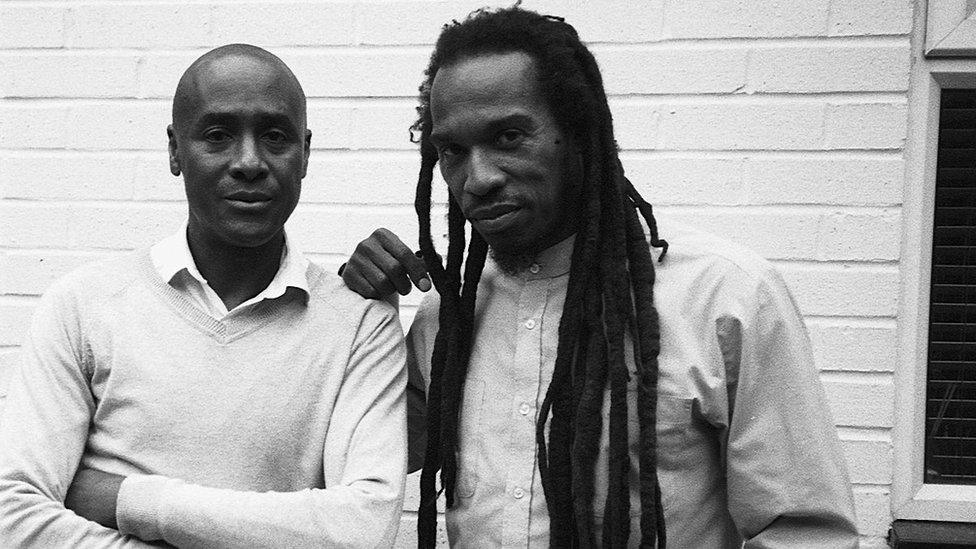

Zephaniah and the Revolutionary Minds performed at Womad Festival in 2017

"Don't get disillusioned and downhearted, don't feel overpowered and defeated. Do what you can," he said in 2020, external.

"Do the little, (or the big), things that make a difference you can see. The tangible stuff. Or take to the streets to do something for the future. Do anything. Just don't give up.

"Don't let them grind you down. Rise up all ye sisters and brothers who know better. Stand firm in the downturn."

- Published8 December 2023

- Published8 December 2023

- Published7 December 2023

- Published7 December 2023

- Published7 December 2023