'Nuance is being lost' - How Israel-Gaza war is spilling into cultural life

- Published

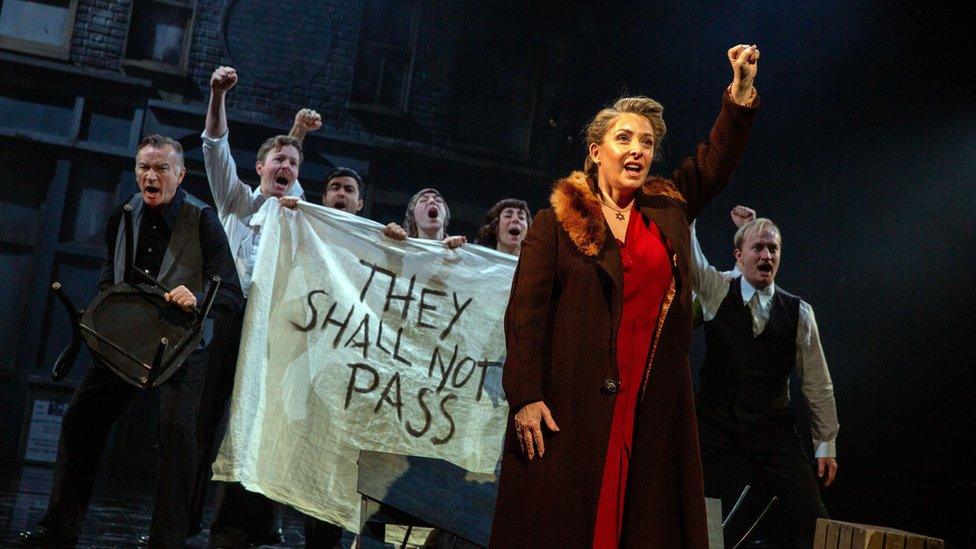

Tracy-Ann Oberman (front) says it feels like some people have "suddenly been educated at the University of TikTok"

The divisions playing out in demonstrations on British streets are also playing out in all our lives - and increasingly in the cultural world too.

With antisemitism and Islamophobia rising, words and actions really matter, but from the pavements to the playgrounds to the playhouses, the Israel-Gaza conflict is polarising opinion - and protests have spilled into the cultural world, with some inevitable backlash.

There have been high-profile examples of cultural figures venturing into the political arena and taking a stance on what's unfolding.

Charlotte Church sang the controversial pro-Palestinian chant "From the river to the sea" at a concert. (She denied she was antisemitic).

The comedian Paul Currie pulled out a Palestinian flag after his show ended at London's Soho Theatre and told Jewish audience members who didn't stand up to "get out". (The theatre apologised and said it wouldn't be inviting Currie back).

And Belfast rappers Kneecap recently appeared on the Late Late Show in Ireland wearing pro-Palestinian outfits. (They apparently flouted rules set by the broadcaster).

How is what's happening in the Middle East - and the tensions being driven here by war and violence there - impacting the UK's arts and entertainment sphere? What role does culture have to heal political divides - or foment them?

They're questions I wanted to explore with figures working in that world, to understand where culture fits at a time that emotions are running understandably high.

Artists as activists

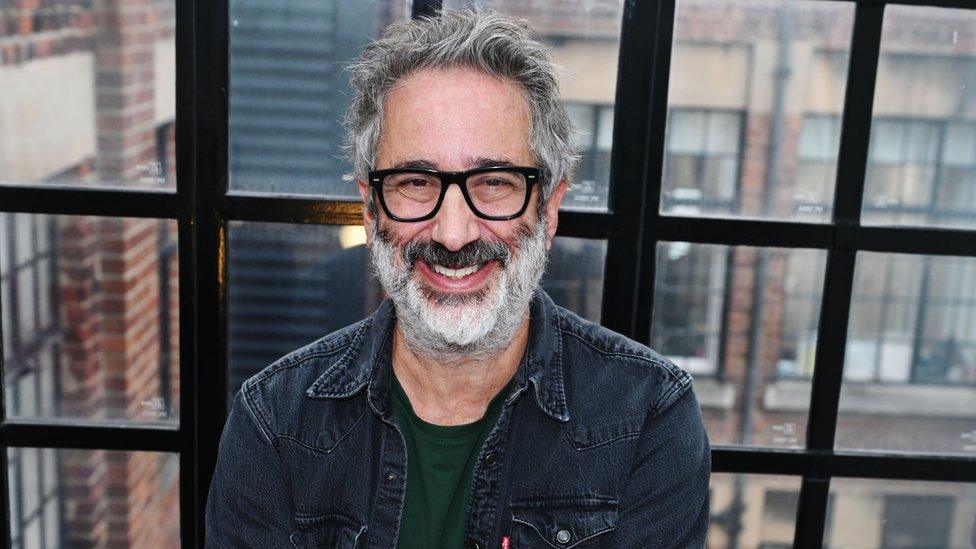

David Baddiel says "it feels there is a lot of support for Palestinians and it may feel that the Jewish voice isn't able to be heard"

Artists speaking up for causes they believe in isn't new. Dame Vanessa Redgrave is almost as renowned for her political views as her acting talents.

It's hardly surprising there are people who want to protest about what's happening in Gaza. The cultural world contains a lot of left-leaning voices.

We've also seen (so far resisted) calls for Israel to be banned from having a pavilion at the Venice Biennale and from competing in the Eurovision song contest.

Dame Helen Mirren and Boy George were amongst the artists to sign an open letter in favour of Israel taking part in what they called "unifying events such as singing competitions". They argued the contest is a crucial way "to help bridge our cultural divides and unite people of all backgrounds".

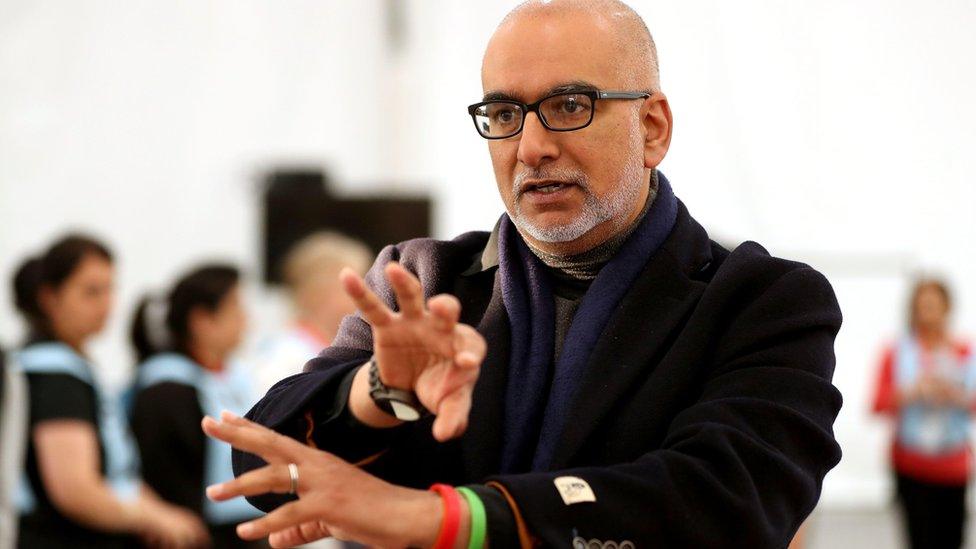

Iqbal Khan describes the current polarisation as "really concerning"

Talking more broadly, the theatre director Iqbal Khan, associate director at the Birmingham Rep, says "the nuance in these issues is being destroyed".

He calls the polarisation across all forms of public life "really concerning", describing "a constant requirement to attach yourself to metaphorical flags and tribes of opinion which don't represent the truth of things."

David Baddiel raised the issue of tribalism on the BBC's Today programme last week.

The comedian, writer and broadcaster said "within the space I come from - culture, showbusiness, artists, whatever - it feels there is a lot of support for Palestinians and it may feel that the Jewish voice isn't able to be heard and cowers a bit at the moment".

He added that Baroness Warsi, the former Conservative deputy chairwoman and his co-host on a new podcast, had told him Muslims feel similarly excluded and silenced in the world of politics and government.

Many would point to Lee Anderson's comments about "Islamists" controlling the London mayor as evidence of that.

'The University of TikTok'

Khalid Abdalla says that with no ceasefire, "what's left for people other than to protest? And if they have a platform culturally, to use it"

The actress and writer Tracy-Ann Oberman told me that "for those of us that have lived with Israeli and with Middle Eastern politics for a very long time, who've worked in advocacy between Palestinians and Israelis and who really understand the geopolitics of the region, we look at people who seem to have suddenly been educated at the University of TikTok to understand the situation - which is of course far too complex to be broken down in a 60-second video".

She adds that "we're in shock because of what they're allowing themselves to say and to be part of".

Each night, more horror unfolds in Gaza, with grim milestones passed and devastating images beamed into our homes.

The conflict was sparked by horrific acts of murder and rape carried out in Israel by Hamas on 7 October, and the ongoing trauma of the hostages held in Gaza.

The actor Khalid Abdalla, who plays Dodi Fayed in The Crown, says "what is very hard is to find a voice which can speak in a way that honours the fact that there is grief and immense legacies on both sides".

But with no political solution, no ceasefire, and "this scale of slaughter, what's left for people other than to protest? And if they have a platform culturally, to use it".

It's "very charged territory" but there is "a moral imperative to take a stand".

Security at the theatre

The tensions in the Middle East can have real world consequences in the UK, not just in racist attacks on the streets.

Tracy-Ann Oberman's timely reimagining of Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice is her attempt to "reclaim" a difficult play full of antisemitic tropes. She wanted people to "see on stage what anti-Jewish hatred looks like".

EastEnders star Tracy-Ann Oberman plays Shakespeare's Shylock

She is a vocal antisemitism campaigner - often "the lone voice in a room with so-called progressive creatives" she says.

She told me she now has personal security as well as security guards who patrol the theatre as she performs her play The Merchant of Venice 1936.

"You've got a Jewish actress who has to have security in the West End because of speaking out about the rapes on 7 October and the industry has not risen up and said 'that's wrong'."

"There should be more people who are saying 'this is unacceptable'. They would find it unacceptable if this was happening to any other minority".

"The country should take this very seriously. As history has proven, what starts with the Jews doesn't end with the Jews".

Clearly, a line is breached if - in these inflamed times - people feel unsafe.

Khan says "the right of an artist to show solidarity with people who are suffering should be absolutely honoured. The minute though somebody's safety is threatened, that's different".

He uses what happened at the Soho Theatre comedy show as an example of that.

"Everybody in that cultural space should feel safe. And I'm not sure in the Soho instance that happened".

(Soho Theatre is still investigating what happened but said while it robustly supported the right of artists to express a wide range of views in their shows, "intimidation of audience members, acts of antisemitism or any other forms of racism will not be tolerated".)

Khan says while "vigorous debate" is useful, people "need to talk without encroaching on another's safety or inciting others to violence".

He believes there is "enormous support culturally for those who oppose antisemitism".

There is also "massive disgust at what is going on in Gaza at the moment, with obviously the understanding that the atrocity that began all of this was the particular set of events on 7 October".

"The response feels appalling to a lot of people… that's the thing that's motivating those voices.

"I was horrified at what happened on 7 October. But the continuing response and the amount, I would describe it as a genocide."

Benedict Cumberbatch held a Ukrainian flag at the annual Santa Barbara International Film Festival in 2022 - just days after Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine

The cultural space being used as a vehicle for activism isn't new. Art never operates in a vacuum.

Think back to 1985 when Spitting Image broadcast a satirical song, released for sale the following year, called "I've never met a nice South African".

It was an attack on that country's apartheid regime and was comedic and pretty uncontroversial.

Fast forward to 2022 and the Baftas took place soon after Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Stars of the film world including Benedict Cumberbatch turned up wearing blue and yellow badges in support, and the Ukraine flag was projected onto the side of the Royal Albert Hall.

Then, last summer, Liverpool hosted Eurovision on behalf of Ukraine - in a sun-filled, joyful coming together of cultures.

But these geopolitical issues are viewed as binary, for the vast majority in the UK anyway.

Apartheid was wrong and the invasion of Ukraine is unjust - that's the prevailing Western narrative, and nobody is taking to the streets or our TV screens to say otherwise.

Those artists picked a side and were lauded for it.

The Israel-Gaza war is also binary for many, with more than 30,000 killed in Gaza and about 1,200 killed in Israel.

But perhaps that leaves no room for nuance or an understanding that Jews in Britain aren't representatives of the Israeli state, just as British Muslims don't speak for Hamas - and that there is genuine fear in our minority communities as tensions rise.

Oberman says "a lot of people don't seem to understand you can both be heartbroken at the situation in Gaza and be appalled at the rise in antisemitism in the UK - the two are not mutually exclusive".

So where does all this leave that hard won right to freedom of expression?

She argues "it's sacrosanct but it doesn't seem to be working for the Jewish community at the moment".

Abdalla says "either we believe in freedom of expression or we don't… artists and workers in culture generally have a responsibility to find ways to express whatever is culturally important to their age".

He believes the cultural arena "has to be a safe space for difficult conversations. The failure in public discourse has fed this crisis and we have a duty to confront that."

"We need our artists, our cultural workers to be finding a way through, to find a language that can speak a way through, as part of finding a political solution."

Related topics

- Published29 February 2024

- Published23 February 2024

- Published8 February 2024

- Published10 May 2023