Harvard University removes human skin binding from book

- Published

Harvard University has removed the binding of human skin from a 19th Century book kept in its library.

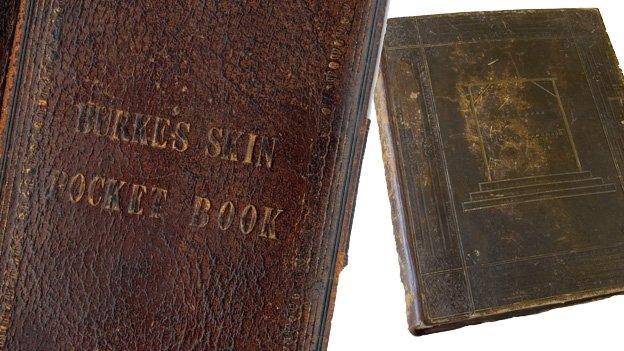

Des Destinées de l'Ame (Destinies of the Soul) has been housed at Houghton Library since the 1930s.

In 2014, scientists determined that the material it was bound with was in fact human skin.

But the university has now announced it has removed the binding, external "due to the ethically fraught nature of the book's origins and subsequent history".

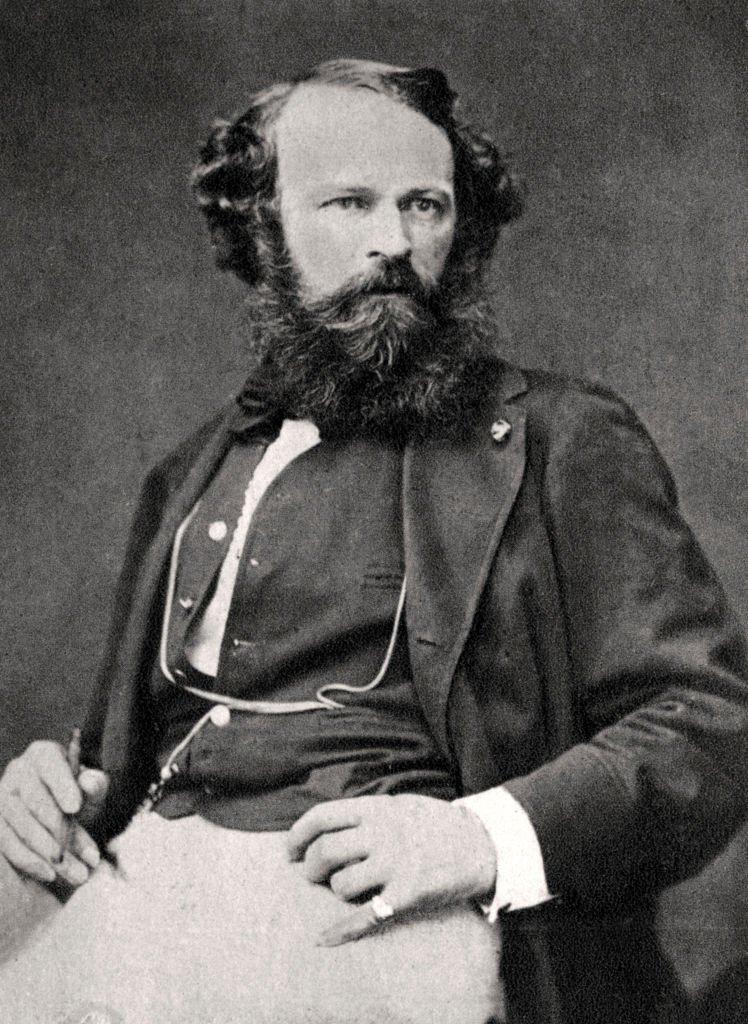

Des Destinées de l'Ame is a meditation on the soul and life after death, written by Arsène Houssaye in the mid-1880s.

He is said to have given it to his friend, Dr Ludovic Bouland, a doctor, who then reportedly bound the book with skin from the body of an unclaimed female patient who had died of natural causes.

Arsène Houssaye penned Des Destinées de l'Ame in the mid-1880s

Harvard University explained its decision to remove the binding, saying: "After careful study, stakeholder engagement, and consideration, Harvard Library and the Harvard Museum Collections Returns Committee concluded that the human remains used in the book's binding no longer belong in the Harvard Library collections, due to the ethically fraught nature of the book's origins and subsequent history."

It added it was looking at ways to ensure "the human remains will be given a respectful disposition that seeks to restore dignity to the woman whose skin was used".

The library is also "conducting additional biographical and provenance research into the anonymous female patient", the university said.

Des Destinées de l'Ame arrived at Harvard in 1934. Located within the book is a note written by Dr Bouland, stating no ornament had been stamped on the cover to "preserve its elegance".

"I had kept this piece of human skin taken from the back of a woman," he wrote. "A book about the human soul deserved to have a human covering."

A decade ago, Bill Lane, the director of the Harvard Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Resource Laboratory, told the Houghton Library Blog, external that it was "very unlikely that the source could be other than human".

'An occasional practice'

In its statement, Harvard said its handling of the book had not lived up to the "ethical standards" of care and that in publicising it, it had on occasion used a "sensationalistic, morbid and humorous tone" which was not appropriate.

It apologised and said it had "further objectified and compromised the dignity of the human being whose remains were used for its binding".

The practice of binding books in human skin - termed anthropodermic bibliopegy - has been reported since as early as the 16th Century.

Numerous 19th Century accounts exist of the bodies of executed criminals being donated to science, with their skins later given to bookbinders.

Simon Chaplin, who in 2014 was head of the Wellcome Library, which holds books on medical history, told the BBC at the time: "There are not a huge number of these books out there, it has been an occasional practice mainly done for generating a sense of vicarious excitement than for a practical motive.

"It generally seems to have been done in the 19th Century by doctors who had access to human bodies for dissection."

Related topics

- Published5 June 2014

- Published20 June 2014