Streatham attack: What do prisons do to deradicalise inmates?

- Published

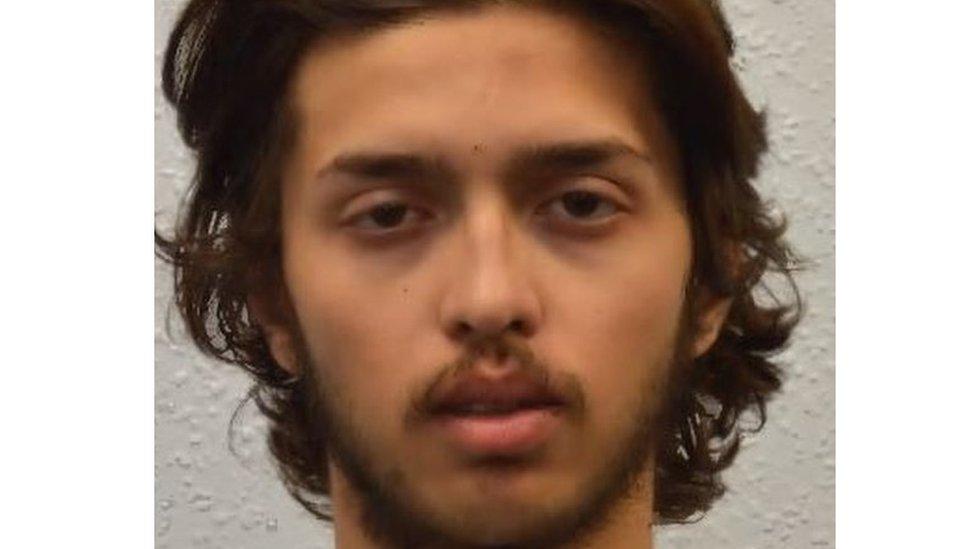

A man shot dead by officers on Sunday, during what police called an Islamist-related terrorist incident, had been out of prison for about a week.

So, what is done in prisons to deradicalise people like Sudesh Amman, who stabbed people on Streatham High Street?

What do we know of Amman's past?

Amman, 20, served half of a sentence of three years and four months for terror offences.

He pleaded guilty in November 2018 to six charges of possessing documents containing information useful to terrorists - and seven of passing them on. The documents included a "manual" on knife fighting.

Before he was jailed, Amman had convictions for having a broken bottle as an offensive weapon and possessing cannabis.

What's done to deradicalise terror offenders?

A programme called Healthy Identities Intervention (HII) is the UK's main in-prison scheme to challenge the thinking of terrorism offenders.

After the 2019 Fishmongers' Hall attack, the creator of the 10-year-old scheme, forensic psychologist Chris Dean, told the BBC there is no certainty all terrorism offenders can be reformed.

It aims to get offenders to think carefully, often over a very long series of counselling sessions, why they chose to turn to terrorist violence. They are asked whether the violence, or support of it, defines their identity.

Amman had previous convictions for having an offensive weapon and possessing cannabis

In some cases, an offender may turn away from violence quickly. But it is often more difficult when prisoners who have spent years in jail, or supporting banned organisations, are involved.

In the case of those aligned to jihadist organisations, prison service imams also get involved in religious counselling sessions. These have been criticised for using chaplains without the detailed knowledge of jihadist ideology required to break down extremist beliefs.

How many prisoners take part?

In theory, every prisoner convicted of a terrorism-related crime is eligible to attend HII sessions, or similar schemes.

Some refuse to co-operate and others may not need specialist intervention because they have found their own way to change for the better.

It is not clear whether the prison service has sufficient resources in place for all the prisoners who may want to take part.

Prof Andrew Silke, another expert in the field, said last year there were waiting lists and some offenders never get seen before their release date., external

How successful are these programmes?

We don't know. Mr Dean told the BBC that HII had seen successes. However, there were also hard cases because of the psychological hold that other extremists, or an ideology, had over the life of an inmate.

The HII programme has not been independently evaluated. One reason is it would be unethical to carry out a scientific trial in which some offenders are released without receiving therapy, just to see if they were most likely to reoffend.

In 2015, the then Justice Secretary Michael Gove asked Ian Acheson, a former prison governor, to review how extremism was being handled. Mr Acheson concluded that the system was full of flaws.

How often do convicts pose a danger after release?

This is the second time that a convicted terrorism offender has come out of jail and carried out an attack, leading to their death at the hands of armed police.

Usman Khan was shot dead by police after he killed two people and injured three others in December's attack at Fishmonger's Hall, London Bridge.

The police have successfully caught other suspects who continue to plot after their release - including a cell in Birmingham who were uncovered planning a marauding knife attack in the city.

What do other countries do?

Some nations separate Islamist extremist prisoners in jails, to prevent radicalisation.

The Acheson review found that in the Netherlands, Spain and France the separation of extremist offenders had worked well. It had improved prison safety and order. That, in turn, had helped the authorities to better target counter-radicalisation schemes at those who would most benefit.

The UK only recently began operating so-called "separation units" for the highest risk detainees. However, there have been reports of disagreement within the prison service over whether they are being properly used.

Saudi Arabia claims to have had the most success, targeting 3,300 inmates since 2005. The authorities there claim an 80% success rate - with the remaining 20% returning to violence.

The offenders go through a number of stages:

Counselling in prison before entering a specialist rehabilitation facility

Intensive cognitive behaviour programmes - aimed at addressing the way they think and respond to situations

Introduction to a wider range of art, cultural, sporting and religious activities to help them return to normal life and society

"After care" once they are back in society

- Published6 February 2020

- Published3 February 2020

- Published19 December 2019