Heathrow expansion: What is the third runway plan?

- Published

The Supreme Court has reversed a decision to block plans for a controversial third runway at Heathrow Airport.

It means that developers can now seek planning permission for the project, which faces opposition from environmentalists and local residents.

What is the Heathrow expansion plan?

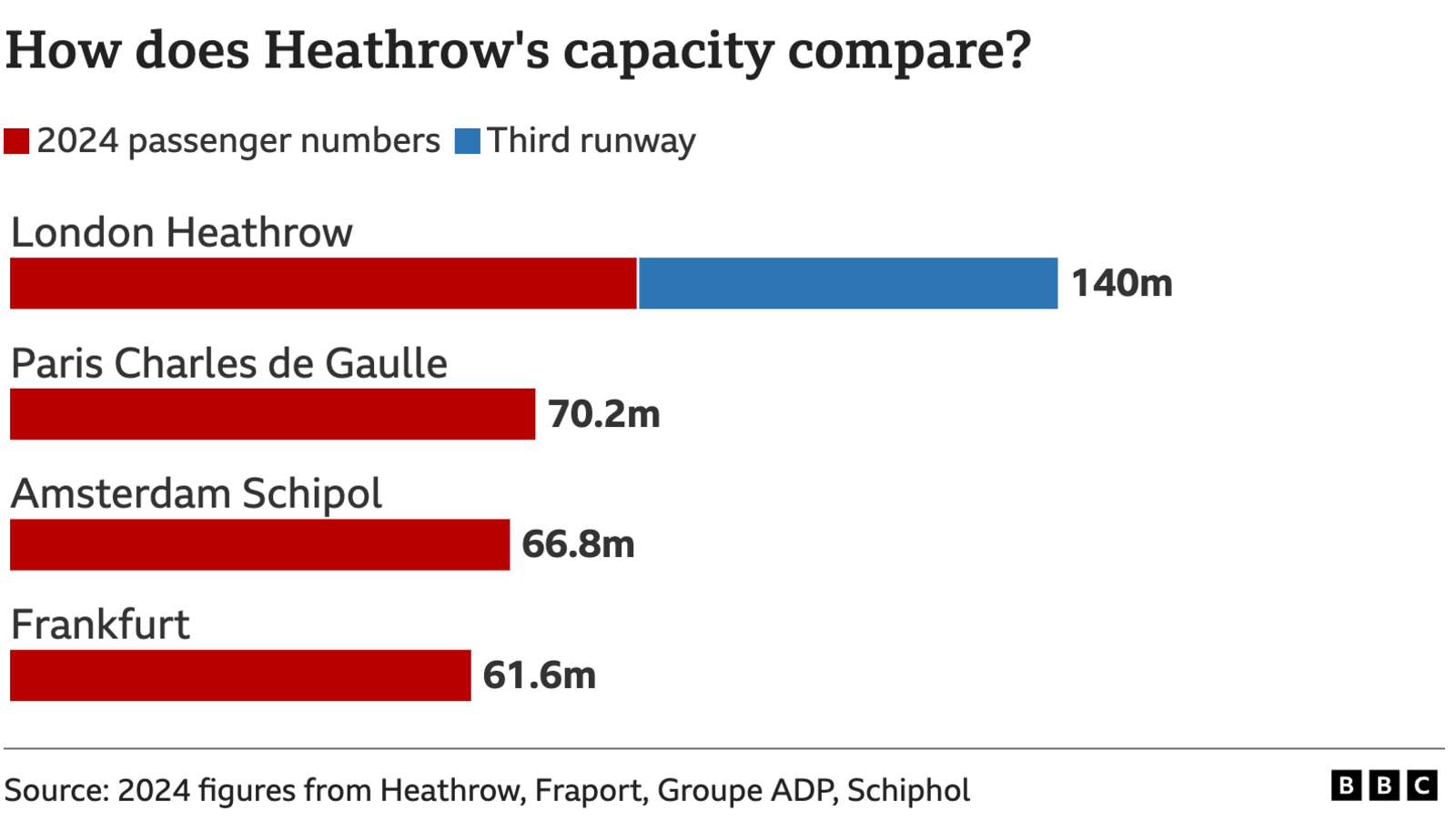

Heathrow is already the UK's busiest airport, serving about 80 million passengers per year. The airport currently has four terminals and two runways.

Supporters of a new runway say it would boost international trade and provide many new jobs.

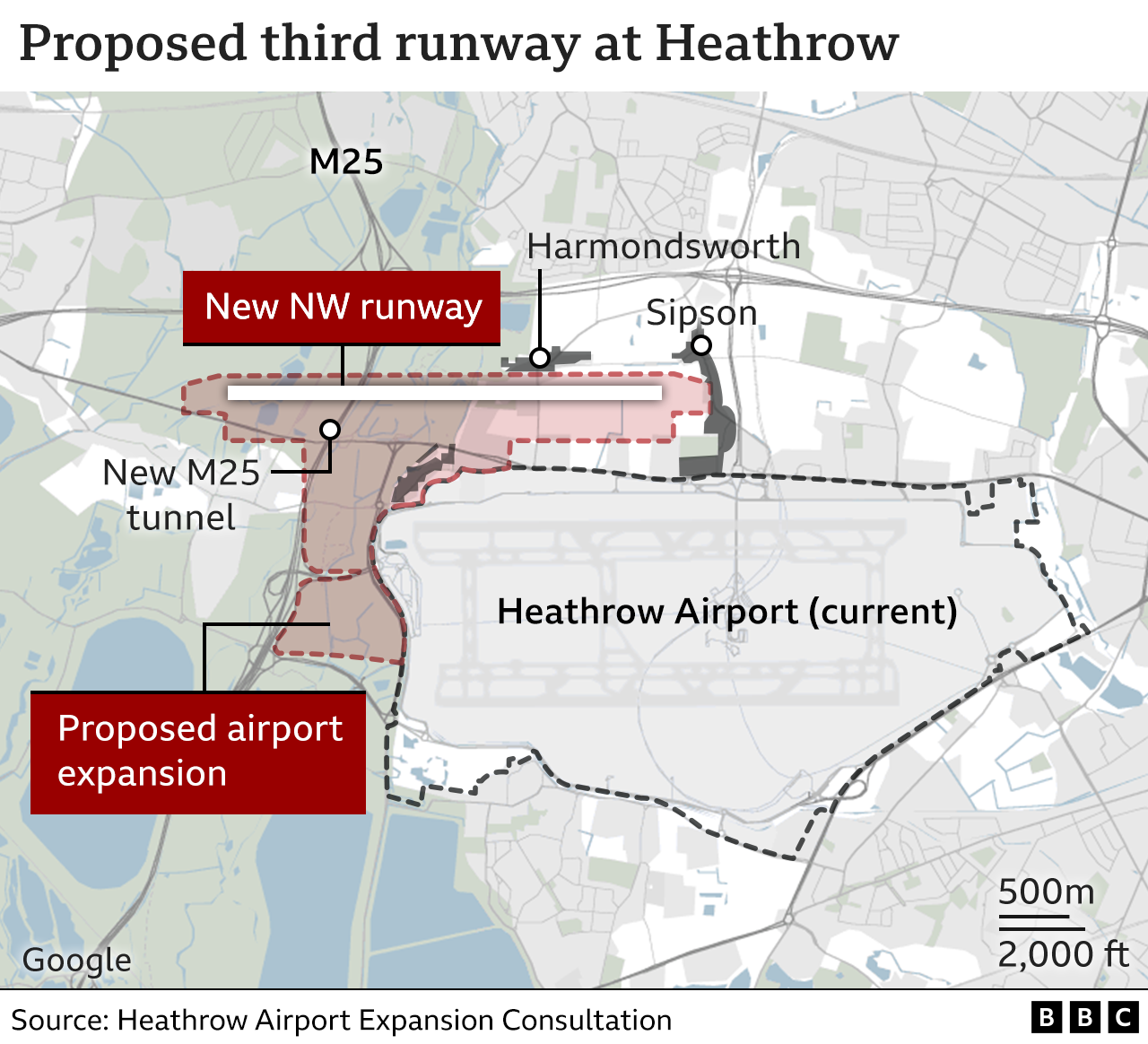

Building the new runway would involve diverting rivers, moving roads and rerouting the M25 through a tunnel under the new runway.

The proposal also includes upgrades to existing terminals two and five and plans to build new car parks.

Heathrow Airport has said the project would be funded privately.

What are the arguments for a third runway?

The expansion would benefit passengers, boost the wider economy by up to £61bn and create up to 77,000 local jobs by 2030,, external according to the Department for Transport.

More than 40% of the UK's exports to non-EU countries now go through Heathrow, according to its chief executive John Holland-Kaye. He said a third runway was vital in order to strengthen international trade links.

"If we don't expand our only hub airport, then we're going to be flying through Paris to get to global markets," he said.

Heathrow Airport also says it would introduce legally-binding environmental targets - including on noise, air quality and carbon emissions.

What are the arguments against?

Local and environmental groups have dismissed Heathrow Airport's assurances and have argued that a new runway would mean unacceptable levels of noise and pollution, as well as adding to the UK's carbon emissions from the increased number of flights.

The proposal also "makes a mockery", external of the government's 2050 carbon neutral strategy, according to Green MP Caroline Lucas.

Rupa Huq - the Labour MP for neighbouring Ealing Central and Acton - has labelled the plan "completely nuts", saying: "Heathrow is the biggest emitter of carbon dioxide in Europe."

Anti-expansion protesters have mounted legal challenges against the government

Campaign groups have also voiced opposition.

"The impact on local people could be severe for many years to come," said John Stewart, who chairs the Hacan group.

"Disruption from construction, the demolition of homes, the reality of more than 700 extra planes a day."

In all, 761 homes are expected to go, including the entire village of Longford.

Heathrow has said it would pay the full market value plus 25% for properties in its compulsory purchase zone, as well as for some houses in the surrounding areas.

When was a third runway first proposed?

The third runway plan has been talked about for many years.

The Labour government approved a third runway in 2009, with former Prime Minister Gordon Brown saying it was needed for economic reasons.

But the plan was later scrapped by the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government in 2010. David Cameron, who became prime minister after Mr Brown, ruled out a Heathrow expansion "no ifs, no buts".

Five years ago Mr Johnson said he would lie down in front of bulldozers to stop a third runway being built

In 2015 an Airports Commission, external, set up to look at London's airport capacity problems, recommended Heathrow as the preferred site for a new runway - a plan which was approved under Theresa May's leadership.

The decision was opposed by several local MPs, including Boris Johnson, whose Uxbridge and South Ruislip seat is next to Heathrow.

He offered to lie down in front of bulldozers to stop the runway's construction. However, when MPs voted in favour of the third runway in 2018, Mr Johnson - then foreign secretary - was away in Afghanistan.

On 27 February 2020, the Court of Appeal ruled the decision to allow the expansion was unlawful because it did not take climate commitments into account.

However, the Supreme Court's decision has ruled the strategy was legitimately based on previous, less stringent, climate targets at the time it was agreed.

What happens next?

The airport can now make a planning application, although this could take more than a year.

It still has to persuade a public inquiry that there is a case for expansion, and the government will have the final say.

Meanwhile environmentalists are expected to continue challenging the project at every stage in the courts - including the European Court of Human Rights.

- Published16 December 2020

- Published27 February 2020

- Published27 February 2020

- Published20 December 2019

- Published22 July 2019

- Published11 March 2019