Covid: What’s the problem with the EU vaccine rollout?

- Published

French Health Minister Olivier Véran receives a dose of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine

The European Union has been criticised for the slow pace of coronavirus vaccinations in its member states.

It has introduced export controls on vaccines produced in the EU after its rollout was hit by supply problems and delays. They were used for the first time on 4 March, when Italy blocked a shipment of 250,000 doses of Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine to Australia.

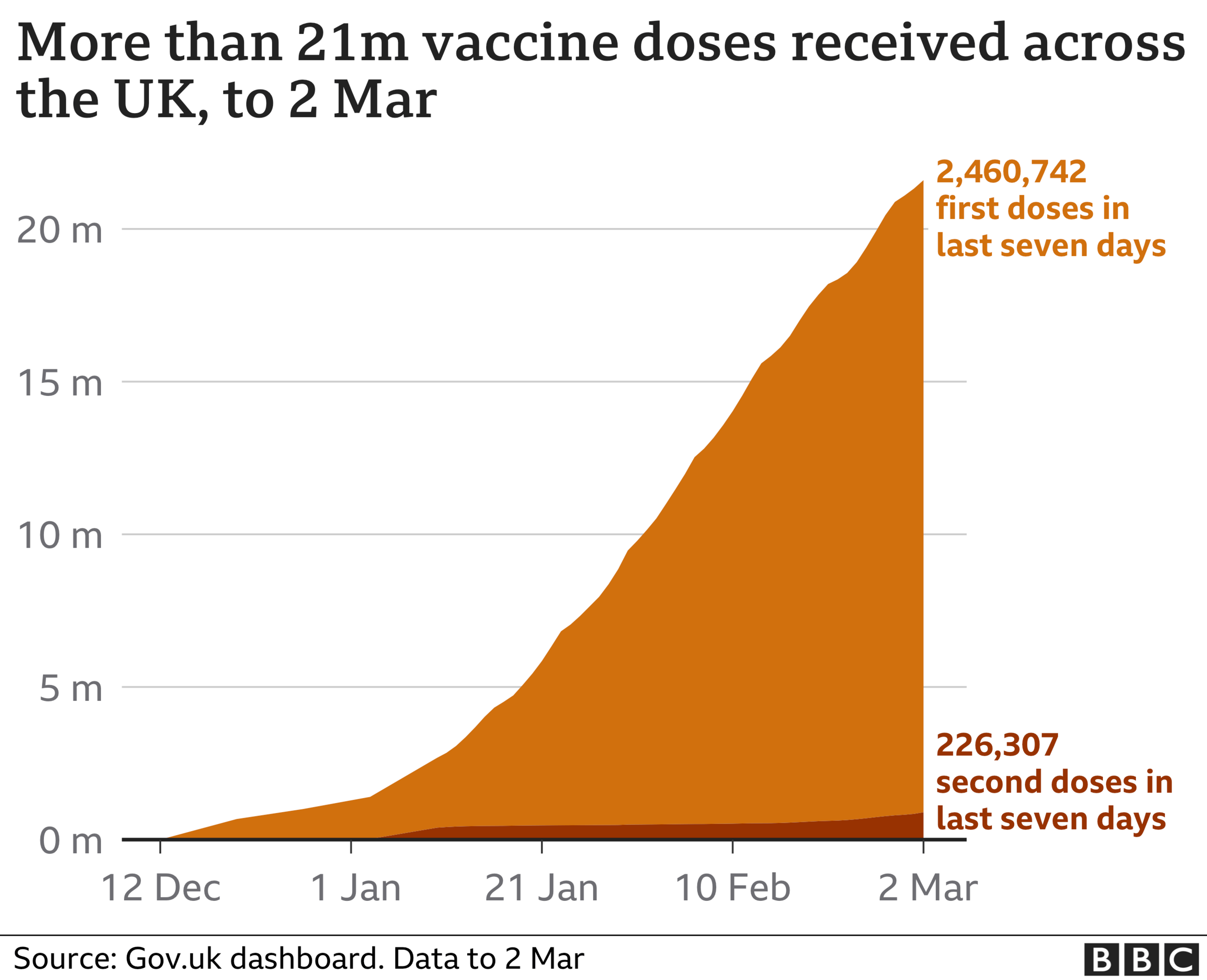

The UK, by comparison, has approved and distributed vaccines to its population significantly faster.

How does the EU vaccine scheme work?

The scheme, set up in June 2020, allows the EU to negotiate the purchase of vaccines on behalf of its member states. It says this can help reduce costs and avoid competition between them.

Member states do not have to join the scheme, but all 27 EU countries chose to do so.

Supply problems

The EU signed a deal for 300 million doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine in December, but there have been problems with production.

The rollout in some countries was delayed because of a temporary reduction in deliveries, to enable Pfizer to increase capacity at its processing plant in Belgium.

The EU doubled its order to 600 million doses and the French company Sanofi agreed to help, external manufacture them.

Distribution of the Moderna jab also ran into problems, with Italy and France both saying they were receiving fewer vaccines than expected.

The Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine has been in short supply within the EU as well, with production shortfalls at plants in Belgium and the Netherlands.

AstraZeneca said the fact that EU contracts were signed later than with the UK left less time to resolve problems, external in the EU supply chain.

On 10 February, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen acknowledged the EU's vaccine rollout failures, saying: "We were late to authorise. We were too optimistic when it came to massive production and perhaps too confident that what we ordered would actually be delivered on time."

The EU has reached agreements to buy three other vaccines, once they pass clinical trials - Sanofi-GSK, Johnson & Johnson and CureVac.

Export controls

The EU introduced export controls on vaccines made in the bloc on 29 January. They were used for the first time on 4 March, when Italy blocked a shipment of 250,000 doses of Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine to Australia.

The EU intended to apply these controls to vaccines moving between the Republic of Ireland (which is in the EU) and Northern Ireland (which is not).

This action would have overridden part of the Brexit deal for Northern Ireland, but the EU reversed this decision, external after widespread criticism.

Public scepticism

In January, the EU medical regulator approved the use of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine for all age groups.

But regulators in a number of EU countries recommended that it should not be used for people over 65.

The French President Emmanuel Macron claimed that the jab was "quasi-ineffective" for this age group - but the UK government and British medical regulators strongly disagreed.

Steven Van Gucht, head of viral diseases at the Belgian health institute, told the Today programme on 25 February that the claim was wrong but "the damage has been done".

France and other EU countries have seen significant levels of public scepticism. German health authorities reported that several hundred thousand doses of the vaccine were not being used.

French government has since revised its stance and approved the AstraZeneca vaccine for people aged between 65 and 74.

Germany, Belgium and Sweden have also suspended their previous recommendations to give the AstraZeneca vaccine only to those under 65, and have approved the jab for all adults.

Separate vaccine deals

Member states are allowed to strike separate deals with vaccine makers which have not signed agreements with the EU.

Hungary has bought two million doses of Russia's Sputnik vaccine, rolling it out in February. It has also granted approval to a Chinese vaccine with Prime Minister Victor Orban receiving the jab.

Slovakia has purchased the Russian jab and the Czech Republic is said to be considering buying it too.

In another move outside the EU scheme, Austria and Denmark have announced they are joining forces with Israel to produce second-generation vaccines against mutations of the coronavirus.

What part did Brexit play?

The UK approved the Pfizer vaccine in November, nearly three weeks before the EU regulators. Some argued that it was only able to move this quickly because of Brexit.

Reality Check looked into this claim and found that the UK's approval of the jab was actually permitted under EU law - a point made by the head of the UK medicines regulator.

The government claimed that being outside the EU allowed it to be more nimble in this area.

The UK could have joined the EU vaccine scheme last year while it was still in a transition phase with the EU, but it chose not to.

If it had, the UK might not have been able to do as many deals with vaccine companies.

The terms of the EU scheme state , externalthat participating countries must, "agree not to launch their own procedures for advance purchase of [a] vaccine with the same manufacturers", that the EU has an agreement with.

The Commission is required to notify these countries of any agreement it is about to conclude and they have five working days to opt out if they don't agree with the terms of the deal. The Commission confirmed that no country has used the opt-out so far.

However, the German government - a participant - signed its own side deal with Pfizer for 30 million extra doses in September.

In January, the European Commission refused to say, external whether this had broken the terms of the EU scheme.

EASY STEPS: How to keep safe

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

CONTAINMENT: What it means to self-isolate

HEALTH MYTHS: The fake advice you should ignore

MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

- Published21 April 2020

- Published26 March 2020