Why are global gas prices so high?

- Published

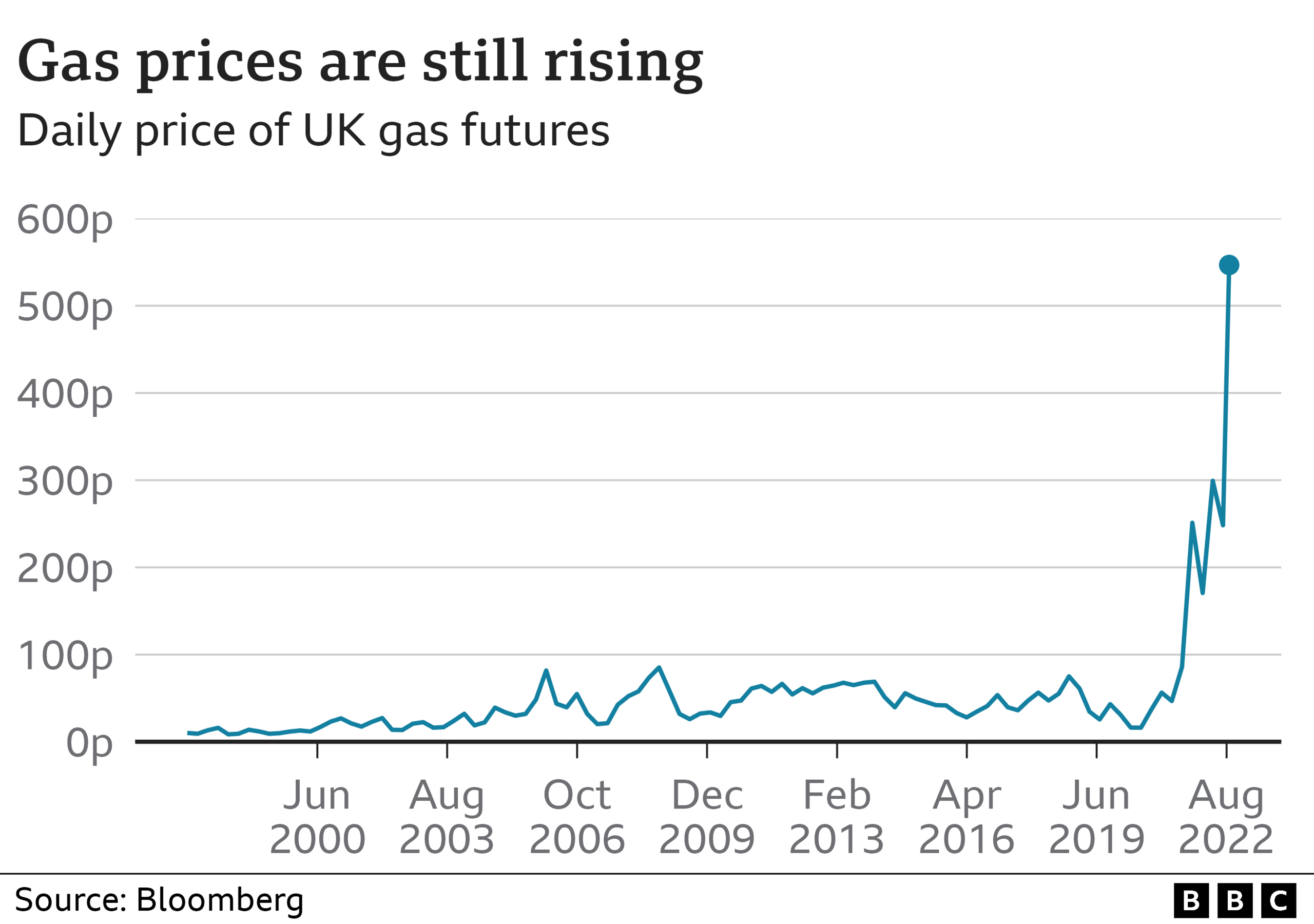

European gas prices are now about 10 times higher than their average level over the past decade.

In February 2021 UK gas was trading at 38p per therm (a measurement of gas consumption). This month it reached 537p per therm. What's driving those high prices?

What's happened in the past year?

Energy prices around the world rose sharply as Covid lockdowns were lifted and economies returned to normal.

Many places of work, industry and leisure were all suddenly in need of more energy at the same time, putting unprecedented pressures on suppliers.

Prices increased again in February this year, after the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

European governments looked for ways to import less energy from Russia, which had previously supplied 40% of the gas used in the EU. Prices for alternative sources of gas went up as a result.

The EU has pledged to reduce its dependence on Russian gas and in July member states agreed to cut usage of gas by 15%.

Germany, for instance, imported 55% of its gas from Russia prior to the invasion of Ukraine. That has now fallen to 35% and it has a long-term plan to end Russian imports.

But at the same time as the pressures of ending reliance on Russian gas, there have been parallel short-term fears that Russia could further restrict or even stop gas supplies, in retaliation for military assistance to Ukraine.

Further pressure comes from Gazprom, Russia's mostly state-owned energy provider, which has suspended gas deliveries to Bulgaria, Finland, Poland, Denmark and the Netherlands over non-payment in roubles.

As European nations stop buying gas from Russia, they need to dramatically reduce their own gas exports - putting yet more pressure on international supplies.

Many have been forced to rely on the international market for liquefied natural gas (LNG) which can be transported around the world in ships, as opposed to being delivered through pipelines.

In previous years European countries have usually bought leftover supplies of LNG from countries like Qatar and the US in the summer, which they put into storage for the winter ahead.

The problem facing them this year is that countries in Asia have already signed long-term contracts to buy up most of the world's LNG before it has even been extracted, leaving a limited amount on the international market.

What is gas used for?

Around the world, the majority of gas is burnt in its country of origin. But in many places that isn't enough and imports are needed, especially during the winter.

Once imported gas arrives at its destination, it is sold to some energy providers at a spot price (reflecting immediate cost and delivery). Some is bought at a future price agreed in advance based on what they expect it to be in the months ahead.

A portion of the gas is also burnt to generate electricity, meaning that high gas prices also push up our power bills.

In 2021, nearly 40% of the UK's electricity was generated by burning gas.

The rest is used for heating and hot water in homes and businesses or saved in storage facilities for the winter.

How are prices set?

The system for setting gas prices differs from country to country. There is no single international price for gas.

Wholesale gas prices are determined by how much it costs energy suppliers to buy gas from domestic and international producers. Natural gas prices rise and fall in line with global demand.

Speculation and fear of imminent disruption can also drive up the price of gas on international markets. This can in turn inflate gas bills for households and businesses.

In the UK for instance, the spot price is calculated using the UK National Balancing Point (NBP), which accounts for gas anywhere in the country's national transmission system. It includes gas imported from abroad, to allow for simplified trading between buyers and sellers.

Now that European countries have entered the market for what remains of the world's unsold LNG, the NBP has to be higher in order to attract imports.

A typical household gas bill in the UK consists of the wholesale price, the operating costs of the energy provider, the cost of maintaining the network, and taxes including VAT and green levies.

Who is profiting?

Companies that extract and transport gas have benefited from a spike in demand. Much of the world's LNG comes from Australia, Qatar and the US. Gas is also produced in Norway and the North Sea.

Between April and June this year, Shell reported worldwide profits of £9.4bn while BP made £6.9bn, more than triple the amount it made in the same period in 2021.