India is holding a mammoth election with nearly

a billion voters

The general election is the largest democratic exercise ever - almost one in eight people in the world can vote.

On 19 April, Indians will begin choosing a new parliament for the next five years, as Prime Minister Narendra Modi seeks a third consecutive term.

Scroll down to find out all about the staggering scale of the exercise, the powerful personalities and issues on which the election will be fought.

Prime Minister Modi is aiming for a third consecutive term in power

Prime Minister Modi is aiming for a third consecutive term in power

Opinion polls put Mr Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its allies ahead. They are up against the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (India), which groups more than two dozen opposition parties including Congress, which was dominant for decades until the BJP took office in 2014.

The election to the lower house (Lok Sabha) is taking place in a bitter atmosphere. The opposition say they have been denied a level playing field, with many leaders raided by federal law enforcement agencies. Congress said tax authorities had frozen its bank accounts for six weeks, hampering its campaign finances. Some opposition leaders, including popular Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal, have been jailed on corruption charges they deny.

The opposition has appealed to India's electoral authorities to intervene but the Election Commission itself has faced questions over its independence. The commission says it is providing a level playing field for all parties and candidates and treating them equally.

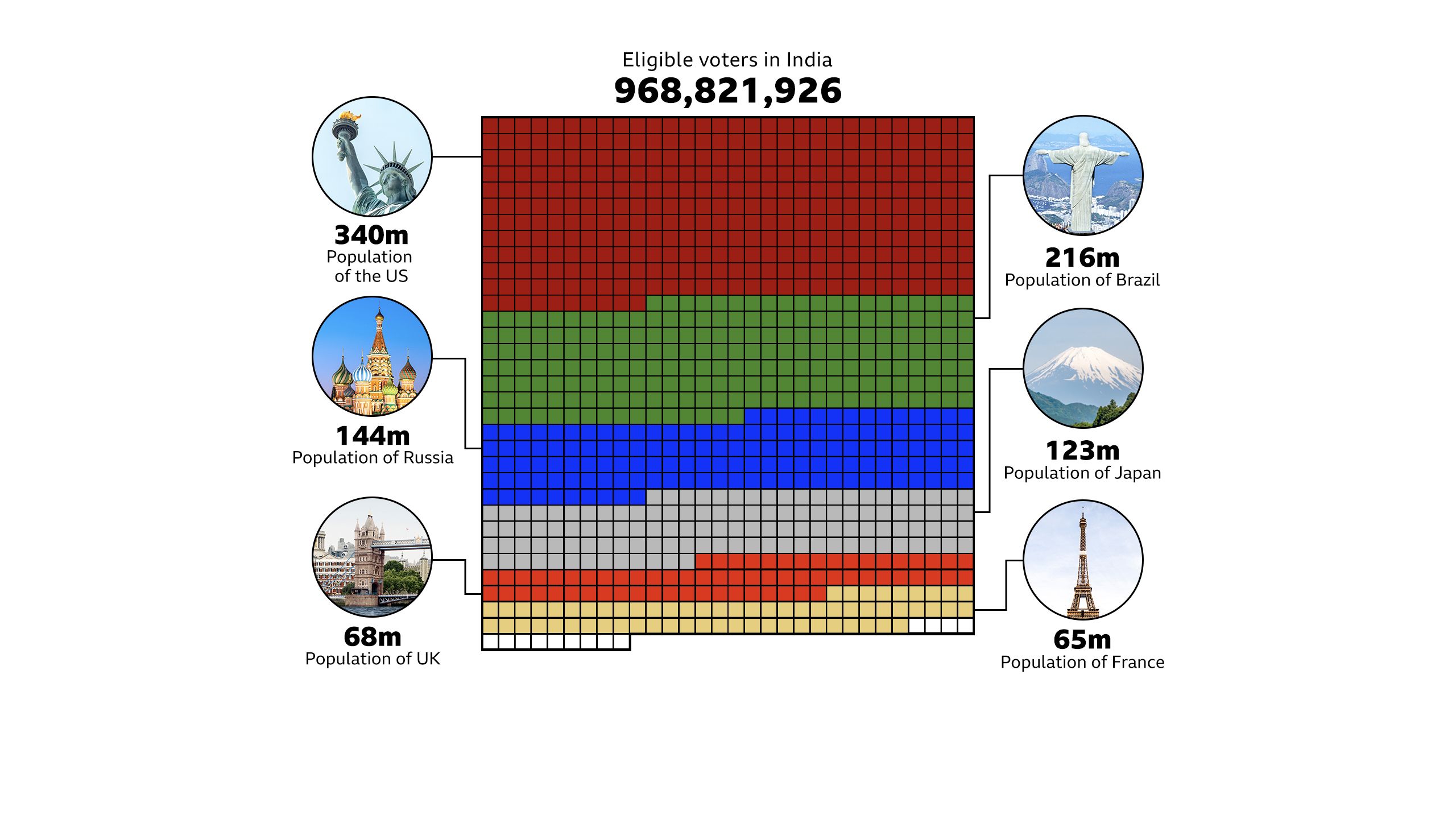

With 1.4 billion people, India is the world’s most populous country and the numbers around the election are mindboggling. Polling to elect 543 MPs will run in seven phases over six weeks, ending on 1 June. Results are on 4 June.

Some 969 million citizens are eligible to cast their ballot. To give you an idea, if you add together the populations of the US, Russia, Japan, Britain, Brazil and France - that comes close to how many Indians are on the electoral rolls. Since we are still a bit short, let's also throw in Belgium.

Voting is staggered for security and logistical reasons. For the first time, the Election Commission has said elderly and disabled people can vote from home by postal ballot.

Nearly 1.5 million polling booths have been set up across the country, with Chief Election Commissioner Rajiv Kumar vowing to “take democracy to every corner of India”.

“Our teams will walk the extra mile to reach every voter, whether they are in jungles or on snowy mountains. We will go on horseback, elephants, mules or helicopters. We will reach everywhere.”

While most polling booths are in schools, colleges and community centres, unusual locations are sometimes chosen - like shipping containers, mountain tops or forests.

Polling booths are set up even in the remotest corners of the country

Polling booths are set up even in the remotest corners of the country

And when the commission says “every voter counts”, it’s not just a slogan. In the 2019 general election, five officials travelled by bus and on foot for two days so that a lone voter – a 39-year-old woman in the north-eastern state of Arunachal Pradesh – could exercise her franchise.

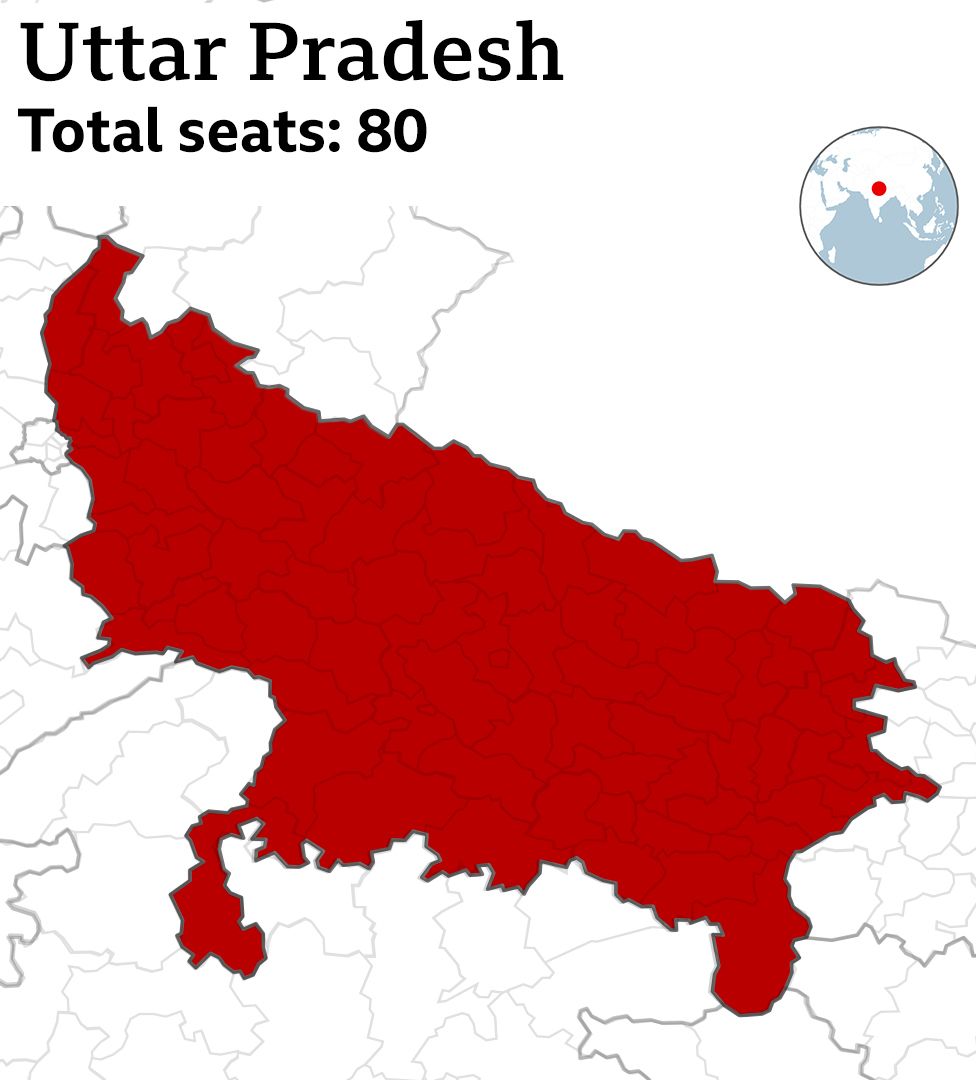

The most politically crucial state is Uttar Pradesh (UP). With more than 240 million people, it’s India’s most populous state and sends more MPs to parliament than any other. Analysts say “the way to Delhi is through UP” and a party that does well here is usually well-placed to rule India - eight of India’s prime ministers trace their roots to the state.

The BJP won 71 of UP's 80 seats in 2014, a figure that dipped to 62 in 2019. Mr Modi, who is from Gujarat, chose UP to make his debut as an MP in 2014. He held his seat in the ancient city of Varanasi in 2019 and aims to do so again this year.

Some of the other key states are:

At the other end of the spectrum are three states in the north-east - Sikkim, Nagaland and Mizoram - and the federally-administered regions of Andamans, Lakshadweep and Ladakh, which elect one MP each.

Most of India - 22 states and federally-administered regions - need only one day for voting but some parts take longer. Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and Bihar will vote in all seven phases.

The elections will decide the fate of thousands of candidates from six recognised national parties - including the BJP, the Congress, Delhi’s governing Aam Aadmi Party and the Communist Party of India (Marxist) - as well as 58 recognised state-level parties. Candidates from many smaller parties will also be in the fray.

All eyes, however, will be on the heavyweights:

Narendra Modi

Prime Minister Modi, who is eyeing a historic third term, remains the frontrunner, with early opinion polls predicting his return. If the 73-year-old wins, he will equal the record of Jawaharlal Nehru, India's first premier.

A polarising figure, Mr Modi remains a mass leader with millions of supporters who credit him with good governance and improving India’s standing internationally. But critics say his brand of muscular Hindu nationalism excludes minorities and he is out to change the secular fabric of the country.

Mr Modi’s use of religion and religious symbolism has proved potent in a country where 80% of the population is Hindu.

His catch-phrase for the 2024 election is “abki baar, char sau paar [this time we’ll cross 400 seats]”, a target the BJP has set for itself and its allies. A party needs 272 seats to win in India's first-past-the-post system - in 2019, the BJP won 303.

Amit Shah

The man powering Mr Modi’s election juggernaut is Home Minister Amit Shah. He’s charted numerous successful election campaigns for the BJP.

Like his mentor, he’s a polarising figure. Supporters say he defends the Hindu faith. He is seen as the driving force behind controversial laws, from scrapping Kashmir's partial autonomy to citizenship legislation that critics call anti-Muslim.

Yogi Adityanath

Mr Adityanath, the shaven-headed, saffron-robed Hindu monk-turned-chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, is considered the biggest mass leader in the BJP after PM Modi. He’s not standing in the general election but is playing a major role in the campaign in the bellwether state.

He's a holy man to his many followers but critics call him a divisive politician who has used public rallies to whip up anti-Muslim hysteria. During his seven years in office, lynchings and hate speech against Muslims have often made headlines.

Rahul Gandhi

Mr Gandhi, who has never won a national election or been a minister, is the most prominent opposition leader. Most of this is down to his lineage: his great-grandfather Jawaharlal Nehru was independent India’s first PM and his grandmother and father both later served as prime ministers.

But as the BJP has risen over the past decade, Congress has shrunk. Some of the blame has been laid at the door of Mr Gandhi, who critics called “the reluctant prince” in his early years in politics.

He’s worked hard to counter that impression, including taking two long treks across the country aimed at “uniting Indians against hatred and fear".

Nonetheless, opinion polls put Congress well behind the BJP.

Sonia Gandhi

When Congress was last in office a decade ago, Mr Gandhi’s Italian-born mother Sonia was considered the most powerful woman in India. But the 77-year-old has been in poor health and has lost much of her political influence.

She maintains a hold over the party as chairperson. In January, Mrs Gandhi moved to the upper house so she is not contesting the Lok Sabha election.

Priyanka Gandhi

One name that does the rounds before every election is that of Priyanka, Mr Gandhi’s charismatic sister – although she has never run for parliament.

Resembling her grandmother – former PM Indira Gandhi – she has campaigned extensively for Congress, winning praise for connecting with people. This time, too, supporters are clamouring for her to stand for election.

Arvind Kejriwal

One opposition figure looming over the election is Arvind Kejriwal, Delhi’s firebrand chief minister who is currently in jail.

He made his name as an anti-corruption crusader whose relatively young Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) beat both the BJP and Congress three times in a row to control the capital. It's also in power in Punjab.

But in March he joined several of his senior party leaders when he was arrested. He's denied corruption charges and accuses the government of being vindictive. Supporters fear his arrest will dent the AAP’s election campaign.

What will decide how Indians vote? Will a grand new Hindu temple prove Mr Modi’s trump card? Will the economy, job prospects or welfare schemes be uppermost in voters' minds? Or will they vote on the basis of caste or religion?

Ram temple

The temple to Hindu God Ram in the northern city of Ayodhya is expected to provide a divine push to Mr Modi’s election pitch by appealing to the majority Hindu community.

Mr Modi inaugurated the temple in January in a grand ceremony televised live

Mr Modi inaugurated the temple in January in a grand ceremony televised live

The temple - which replaced a 16th Century mosque torn down by Hindu mobs in 1992, sparking riots in which nearly 2,000 people died, was inaugurated with much fanfare by the PM in January.

The event was broadcast live on TV; schools, colleges and most offices were given a day off and people were encouraged to watch the ceremony.

Economy

Could PM Modi’s vow to make India “a developed nation by 2047”, its independence centenary, chime with voters?

India – with its GDP at $3.7tn (£3tn) - is the world’s fastest growing major economy. Last year, it beat the UK to become the fifth largest in the world and is on course to reach $7tn by 2027, which would see it leapfrog Japan and Germany into third spot after the US and China.

But the spoils of India's boom are concentrated in few hands and inequality remains high. India ranks 140th in terms of global per-capita income and more than 34 million of its citizens live on less than $2.15 a day, even though government data shows "extreme poverty" has reduced a lot.

Jobs

Many voters will be thinking of jobs. Seven to eight million young Indians enter the labour market annually, but millions are unable to find work.

Recent government data shows falling unemployment and a steady increase in labour force participation - to 57.9% in 2022-23 from 49.8% five years earlier. But experts point out most new jobs are low-paying and poor quality - for example in agriculture or women doing unpaid family work.

A telling indication of distress is that millions more are now signing up for the $3-a-day government rural job scheme. Thousands are even ready to migrate to war zones for work.

Electoral bonds

They were meant to clean up murky political financing, but electoral bonds were recently banned by India’s top court, which ruled them "unconstitutional". The court also ordered the government-run State Bank of India (SBI) to provide details of who bought them and how much parties received.

The fact that the BJP was the biggest beneficiary – securing almost half of bonds worth 120bn rupees ($1.4bn; £1.1bn) donated between 2018 and 2024 – isn’t looking good on Mr Modi’s report card.

Youth Congress members burn posters of PM Modi during a protest against electoral bonds

Youth Congress members burn posters of PM Modi during a protest against electoral bonds

Reports have linked many donations to companies being investigated by government anti-crime agencies. Calling it the "biggest scam in Indian history", opposition parties allege the agencies were used for “extortion”, which ministers have denied.

Welfare

The scale of India's welfare state is staggering: the Modi government claims it has spent hundreds of billions of dollars to help poor households, reaching more than 900 million people. A number of state leaders have also invested heavily in welfare schemes.

But does that free sack of rice or money to build toilets prompt people to vote for a party? Analysts say such schemes can help, but that they are unlikely to be the only driving factor.

Divisive politics

India has long had religious divisions but critics say fault lines have deepened in the decade since the BJP won power. They say India is becoming a Hindu state where its secular status is increasingly being challenged and its 200 million Muslims - the country's biggest minority, accounting for some 14% of the population - are marginalised. The government rejects this, saying it is inclusive.

India's capital Delhi witnessed Hindu-Muslim riots in 2020

India's capital Delhi witnessed Hindu-Muslim riots in 2020

In the last Lok Sabha, the BJP did not have a single Muslim MP. Rights groups and activists also point to increasing violence against Muslims, especially in states governed by the BJP. The government denies accusations it has a divisive agenda and its supporters appear largely unconcerned by such criticisms.

The democracy question

The election comes amid accusations from the opposition, activists and global rights organisations that Indian democracy is under threat. Rahul Gandhi has accused the government of targeting opposition leaders, spying upon them and imposing constraints on parliament, the judiciary and the free press.

Organisations like Human Rights Watch say the Indian authorities have used politically motivated criminal charges, including terrorism, to jail many critics and foreign funding rules to harass the opposition, rights groups and the press - charges the government denies.

Credits:

Report: Geeta Pandey

Illustrations: Chetan Singh

Production: Shadab Nazmi

Photos: Getty

Published on: 16 April, 2024