Searching for my slave roots

The poet Malik Al Nasir has been on a journey to find his roots as a black Liverpudlian. It's a journey that has taken him back in time and halfway around the world, before returning him right back to the city where he began.

It started with a photograph from the 19th Century of a man who could have been my double.

It was one o’clock in the morning and I was watching a TV documentary about 100 years of black footballers.

This was 2002, and there weren’t many programmes about black people, so it was worth staying up for.

Then a face appeared that made me catch my breath.

A Victorian footballer.

He looked comfortable, he didn’t look out of place, he looked like a boss. Very much a black British gentleman.

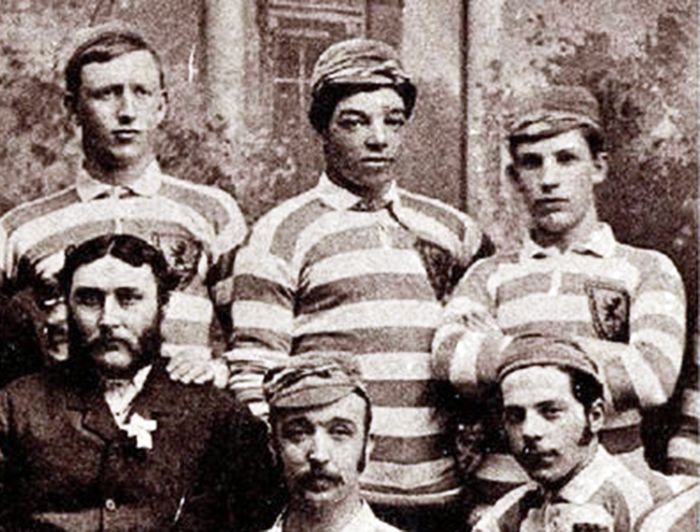

Andrew Watson (centre, standing), 19th Century Scottish footballer

Andrew Watson (centre, standing), 19th Century Scottish footballer

His name was Andrew Watson - the same surname as my Dad. And he was from Demerara in Guyana, just like my Dad. [Malik changed his name from Mark Watson after converting to Islam].

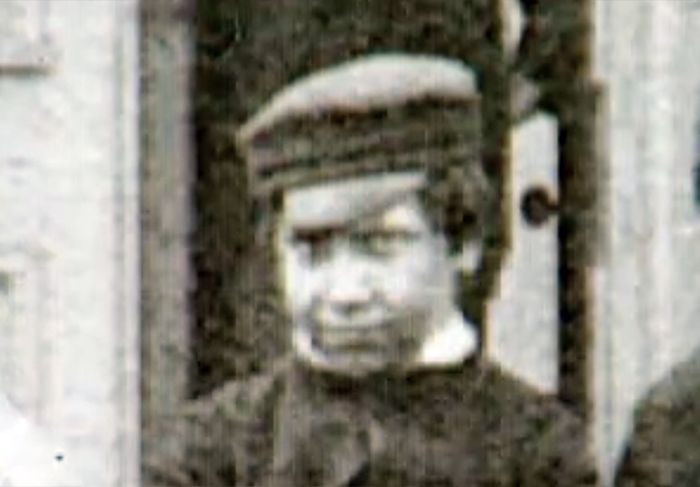

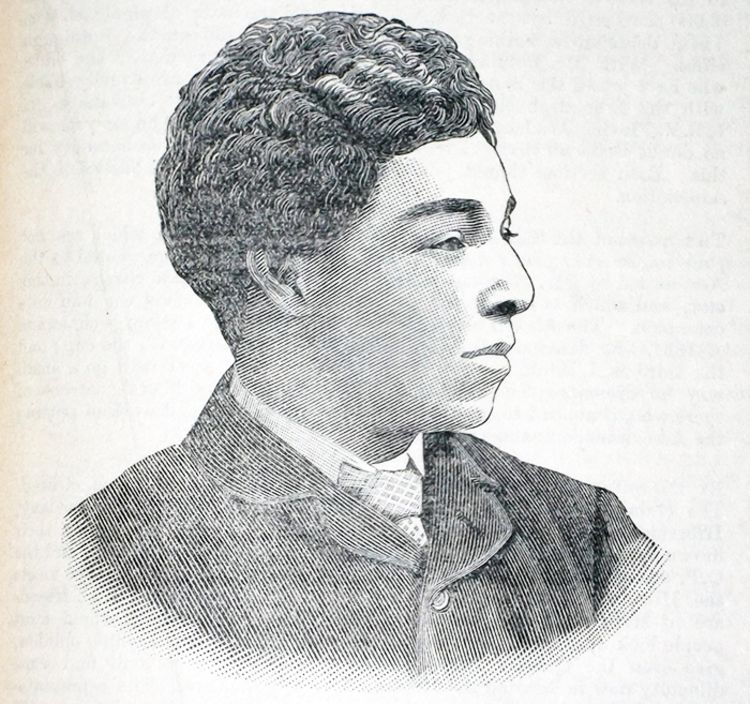

There was another image of him in the documentary, but this time as a young boy at a grammar school in Halifax. Above my Mum’s TV set was a picture of me at about the same age - we were identical.

Andrew Watson as a schoolboy

Andrew Watson as a schoolboy

Minutes later, the phone rang. It was my Mum. She said, “Turn on the BBC.” I said, “Mum, I’m already watching it.”

“He looks just like you,” she said.

Watson was born in 1856 in Demerara. He came from money, he was well-educated at private schools and at university in Glasgow, Liverpool and London.

He was a significant footballer in the 19th Century. In the 1880s he played for Queens Park, winning three Scottish cups. At the time they were one of the biggest clubs in the world.

He also played three games for Scotland at international level. He was described as an inspiration, captaining the national side during their 6-1 win over England.

We looked identical. But Andrew Watson’s life was very different to mine.

Growing up

Growing up

Warning: This chapter contains racial slurs

The first time I was racially abused was in school. It was 1972. I was six years old and sitting in school assembly.

The head teacher was playing a taped story called The Story of Little Black Sambo.

I could hear every offensive line booming out at the morning assembly. Other kids were laughing, giggling and pointing at me.

It made me feel like I didn’t belong, that there was something wrong with me. But we were told not to take offence because it was the teachers who were playing it.

In England in the 70s it was normal to see books with titles like Ten Little Nigger Boys or The Proud Golliwog.

Nobody seemed to think this was a problem.

1968: Malik Al Nasir aged two

1968: Malik Al Nasir aged two

I was already living in a poor neighbourhood, but I was also dealing with racism - in the classroom, from friends, on the TV in my house.

I had to fight most days in school. I was attacked on a daily basis, in and out of school but it was always me who had to see the head teacher for punishment. I was considered the troublemaker for being bullied by the kids the teachers were egging on.

And life was about to get a lot worse. My Dad had a stroke, it was Christmas 1974. He was paralysed and stayed in hospital until he died.

My Mum, a white woman, was now a single parent with four black kids. She couldn’t cope with living in a poor white area at a time of heightened racial tension. She was a target of a lot of hostility.

She was a very strong woman but even she was powerless against this toxic background.

I was expelled from school at the age of nine and taken into care.

Malik aged nine

Malik aged nine

I remember everything about that first night, as if it was now. It was the most traumatic event of my life.

I was stripped, washed and placed in a locked room. I spent 14 days in isolation there, in solitary confinement. I remember the bars on the windows, nobody spoke to me, food was pushed through a hole in the door like a prison.

I still remember banging on the windows, screaming and begging to be let out.

It was called the Liverpool Children’s Admission Unit. It was on Acrefield Road in Woolton. Thank God it’s been knocked down now.

It was a dilapidated old Victorian mansion, run by a man who looked like Gomez from The Addams Family. He had a mynah bird in the office, a big black thing that used to talk.

The place was always musty, stinking of damp. Plaster was falling off the walls and in the communal lounge there was a huge block that had fallen off - the hole was so big, kids could fit inside.

I was moved from one children’s home to another, suffering physical abuse and racism.

In many of the homes, staff would beat us, but nothing was done because the reports to social workers were written by the people beating us.

One home in Warrington had a farm, so we had to dig foot-deep trenches a couple of hundred metres in length, and plant potatoes.

The social workers would sell them to the public. It was forced labour.

I missed 18 months of primary education and had less than two years in secondary school.

I also spent time in an approved school in Manchester, which was brutal - I had a tooth knocked out and I was stabbed.

I left the care system in 1984 at the age of 18, semi-literate, and was placed in a hostel for homeless black youths.

I had no qualifications to get a job, no social structures to support me, not a penny to my name. I was on my own on the streets, at a time of racial tensions. The Toxteth riots were only a recent memory.

The Toxteth riots, July 1981

The Toxteth riots, July 1981

I was totally lost – I did not know who I was, where I belonged, or what would become of me.

But that year, things started to change.

Gil Scott-Heron, singer, poet and civil rights activist, writer of The Revolution Will Not Be Televised and I Think I'll Call It Morning, was playing in Liverpool.

I sneaked into a gig he was playing at the Royal Court Theatre.

Gil Scott-Heron on stage at Royal Court Theatre, Liverpool (photographer: Penny Potter)

Gil Scott-Heron on stage at Royal Court Theatre, Liverpool (photographer: Penny Potter)

The atmosphere was something else - it was electric, and Gil was in perfect unison with his audience.

Afterwards I made my way backstage, and we got talking.

We never stopped.

Gil became my mentor. It completely changed my life.

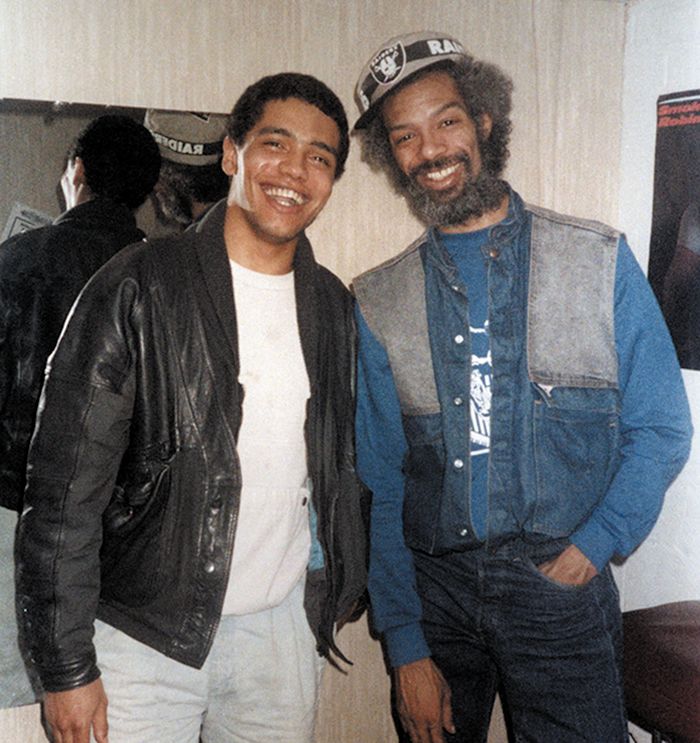

Malik with the singer and poet Gil Scott-Heron

Malik with the singer and poet Gil Scott-Heron

Whenever he was in the UK, I’d be on tour with him. I learned to set up the drums. I did the laundry, the merchandise, anything.

But more than that, Gil inspired me to write poetry, and this allowed me to heal and confront my past.

But what was my history?

All I knew was that I was probably descended from a slave.

I knew about the Vikings, the Romans, World Wars One and Two, the Empire.

But the black figures were savages or else they were Uncle Ben on the rice packets or the gollywog on the marmalade jar.

Andrew Watson, illustrated in the Scottish Athletics Journal

Andrew Watson, illustrated in the Scottish Athletics Journal

Andrew Watson was the first historical black role model I could be proud of. I wanted to know about his life.

I dug deeper and started two family trees - one for me and one for him.

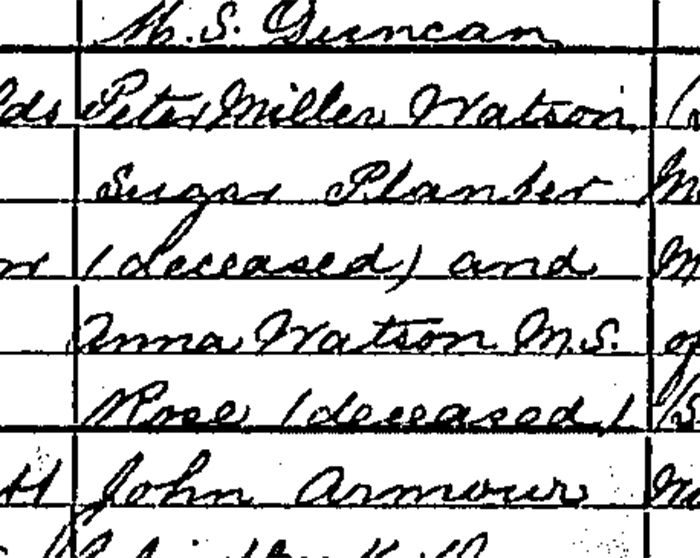

Andrew Watson’s marriage certificate named his father as Peter Miller Watson.

Peter’s job title was “sugar planter”. He was born to a prosperous family in northern Scotland in 1805. By the 1830s he owned, and was running, sugar plantations in Demerara.

Andrew Watson's marriage certificate names his father as "Peter Miller Watson, sugar planter (deceased)"

Andrew Watson's marriage certificate names his father as "Peter Miller Watson, sugar planter (deceased)"

Peter Miller Watson’s mother, Christian Robertson Watson (1780-1842), was one of three sisters apparently known as the “three fair maids of Kiltearn”, a parish just north of Inverness.

The eldest was Ann Robertson, who married Charles Stewart Parker. He was based in Glasgow, involved in insurance and shipbuilding, and he owned sugar plantations in Grenada.

The youngest sister was Elizabeth Robertson who married a man from Cheshire called Samuel Sandbach. He dominated a company called Sandbach Tinne & Co, described at the time as trading “sugar, coffee, molasses, rum and prime gold coast negros”.

A picture was emerging of families inter-marrying, with shared business interests in a slave-owning dynasty that lasted for generations, accumulating staggering amounts of money.

At this point all I knew was that I looked similar to Andrew Watson. Our ancestors were born in the same country and we shared the same surname. But if we were related, did that mean that I was also descended from slave owners?

My instinct said I was, but still it was an uncomfortable prospect.

I remembered how my Dad once said to me, “One day I’m going to take you back to the sugar cane.” It never happened because he died when I was 13.

It was time to go back to where my Dad had come from.

Back to the sugar cane

In 2008 I headed for the South American country of Guyana, armed only with the name of a village - Weldaad - and the knowledge that my Dad, Reginald Wilcox Watson, had once lived there.

I had no idea of what would unfold, but it felt like going home.

Stepping foot on Guyanese soil at Cheddi Jagan Airport wasn’t like arriving at Heathrow.

The airport was small and austere. Outside there were palm trees. The area had been carved out of a tropical rainforest.

Malik arriving in Guyana, 2008

Malik arriving in Guyana, 2008

The first stop was Georgetown, to scan the national archives.

Despite this being the capital, there were no high-rise buildings, and the older buildings were made out of timber. It didn’t take long to track down the information I needed.

I couldn't find any marriage record, but the electoral roll confirmed there was a Peter Miller Watson in Guyana, who was eligible to vote because of his ownership of two sugar plantations - Le’ Bonne Intention and Plantation Zeebrugge.

His date of birth matched that of the sugar planter named in Andrew Watson’s marriage certificate - proof that the father of one of the world’s first black footballers owned plantations and slaves, and that he had a relationship with a black woman.

It was time to head to the tiny village of Weldaad, along the coast from Georgetown.

What should have been a straight 90-minute drive took three hours, as the car bounced around on bumpy roads, held up by donkeys, cows and goats - all this in oppressive humidity.

But Weldaad was beautiful - the lushest of vegetation, 60ft high coconut palms, green undergrowth and fruit trees.

Poking out between it all were telephone poles, the only thing that looked modern in the whole town. It was like stepping back in time.

In Liverpool I was used to seeing flocks of seagulls but this place hummed to the noise of parakeets and macaws of blue and green with big long tails.

The road to Weldaad

The road to Weldaad

The rainforest had been cut back to make way for cane fields and rice paddies with canals everywhere. They'd been built by slaves under Dutch colonists 200 years ago, to move goods around the fields to the processing plants - a tropical version of Holland.

Cows were wandering freely around the coconut palms and timber frame houses.

It struck me that whatever riches were gathered from these fields, none of it trickled down to the people remaining today.

Weldaad was such a rural area and everyone was so kind to me, more than happy to help.

The local people talked about a man long dead called Teacher Watson, who lived in the next village. Could that have been my grandfather? Yes, it was just a surname but it was all I had to grab onto.

There was a man in the village called Mr White, who studied family history. Frustratingly he had never heard of any Watsons, but by a twist of fate, the day after talking to me, he heard two old ladies talking in a bank, one of whom mentioned that her maiden name was Watson.

Mr White introduced himself and took her number to give to the “man from England looking for his family”.

The lady lived in a timber house raised on stilts to protect it from the floods. It was evening by the time I was outside her home.

At the top of the steep wooden steps, the door opened and I was greeted by a smiling old lady. Her name was Withyeline, she was 82 years old, and on the wall above her was a picture that was the spitting image of my father.

“Reg Watson?” I asked.

“Yes,” she replied.

Did I have a sister twice my age? My heart was racing.

“Reginald Wilcox Watson?” I asked again.

She paused and said “No, that’s Reginald Daniel William Watson. Your father is my Uncle Reg.”

I was confused but then it hit me - our fathers were half-brothers and both called Reg!

So Withyeline was my first cousin. She told me she’d lived with my father before he left Guyana in the 1930s.

Withyeline, Malik's cousin in Guyana

Withyeline, Malik's cousin in Guyana

We shared a grandfather, George Edward Watson. Withyeline confirmed that this was indeed Teacher Watson. He was an educated man, a schoolmaster who also taught my father to read and write.

She revealed that my father was meant to inherit land, but because he’d left for England he never got his share.

I wanted to know more about the land. Was it a connection to Andrew Watson?

The next day I went back to the land registry, and looked at maps with plots carved out. The Watson family land, where Withyeline was now living, was in what was once called the Woodlands plantation, just north of the region's main sugar refinery.

Frustratingly there was no clear connection between this plantation and Peter Miller Watson.

But why did my side of the Watson family inherit acres and acres of plantation land?

After five days of searching, it was time to head back to Liverpool.

I had found family members. I knew the exact land where my ancestors lived, and confirmed the name of Andrew Watson’s father but there was still so much more I needed to know.

The archives

It would be 10 years before I found the next clue.

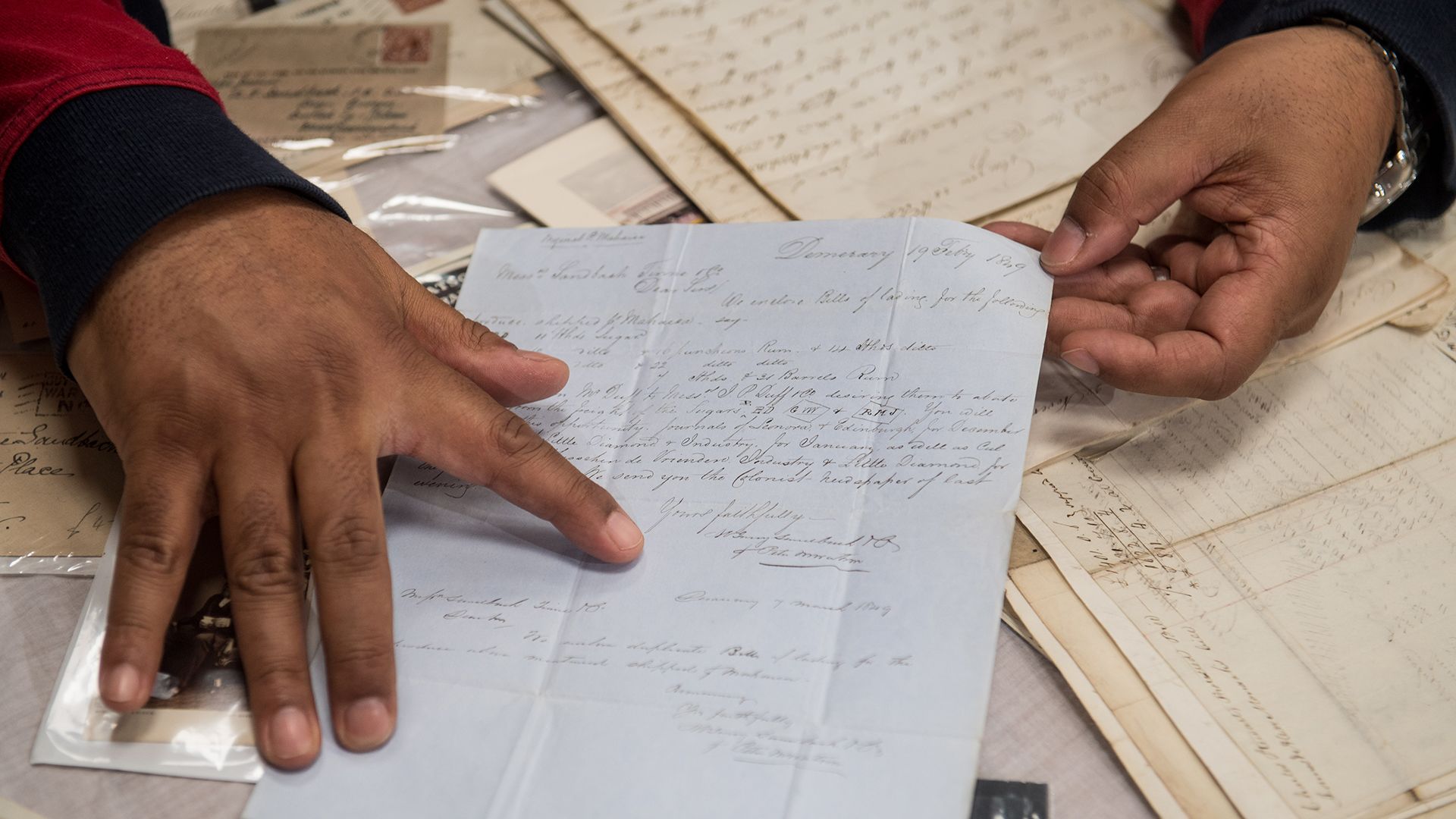

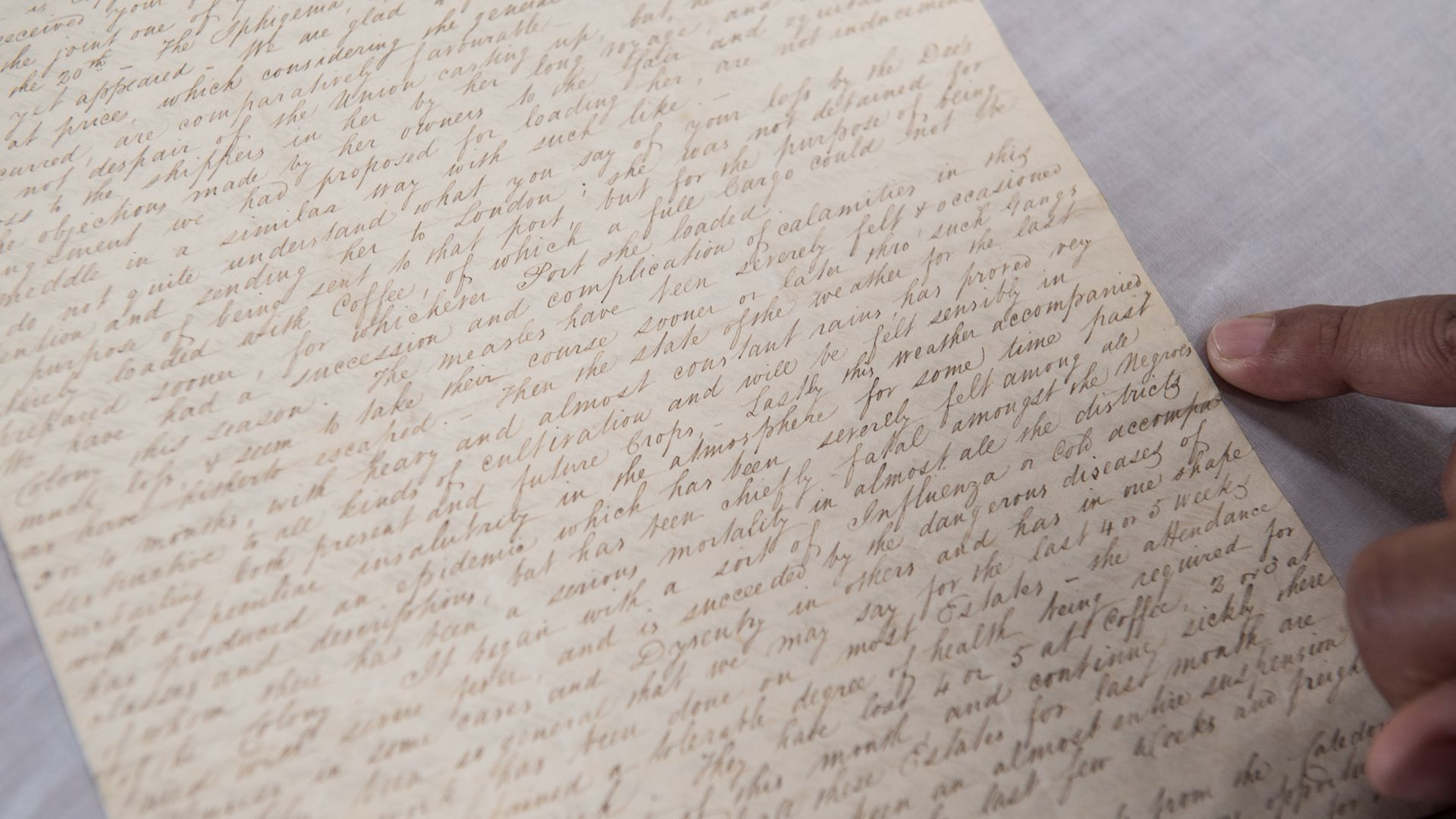

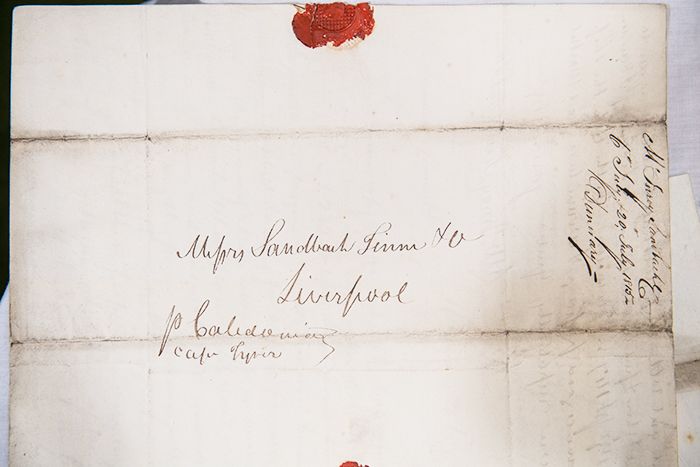

On eBay I spotted a collection of ephemera for sale - handwritten letters with wax seals and postmarks.

Stamp dealers collect these items for their rare postmarks. There was little clue in the listing to what was in the letters, but the seller described them as 19th Century correspondence detailing the sugar and slave trade, specifically addressed to and from Liverpool, Demerara and Glasgow.

Money was tight but I took a chance, and paid thousands of pounds for all of them.

It was a gamble that paid off.

There were more than 100 letters, mostly covering the mercantile slave-owner dynasty that began with Peter Miller Watson’s grandfather, George Robertson, in Grenada in the 1790s. George's partners were Samuel Sandbach and Charles Stuart Parker, Watson’s uncles by marriage.

They moved operations from Grenada in 1795 after a slave revolt, and relocated in the Demerara region of Guyana. In 1813, the major trading arm of this family enterprise took on a Dutch partner, Phillip Frederick Tinne, and it became known as Sandbach Tinne.

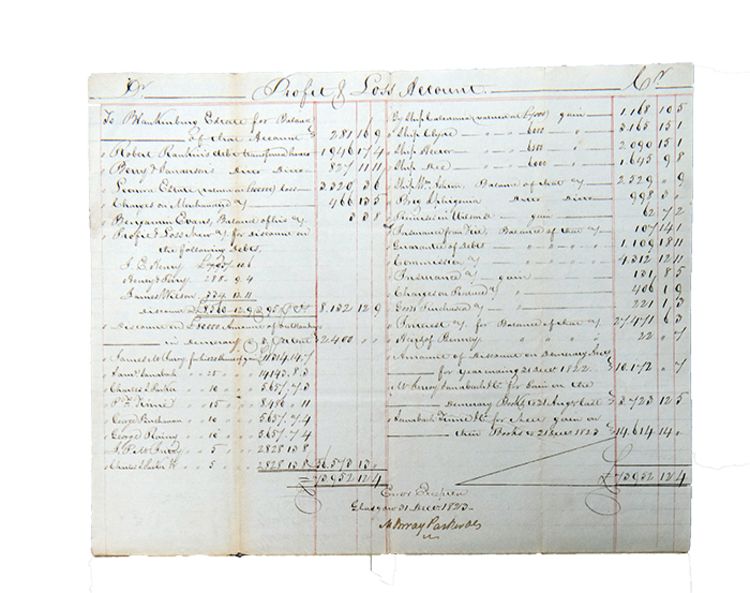

The papers were the complete accounts, profit and loss as well as balance sheets of the entire operation from 1808-1880.

They detailed the names of the company’s plantations, the number of acres, the insurance, the fleet of cargo ships built and insured, and where the cargo was transported.

It also confirmed that the company owned the plantations - and slaves - where my family lived in Guyana.

I was shocked. The correspondence provided extensive written evidence of the company’s slave-trading operations, the numbers of slaves owned and the massive amount of money this operation brought in.

The archive was a gold mine, but it was overwhelming too, looking at this dark sinister past, filled with centuries of suffering endured by black people. I was also trying to comprehend the fact that I too might be related to the exploiters, the slave owners.

Here it was documented that Samuel Sandbach joined the company in Grenada as a low-level clerk, and moved to Demerara when the company relocated in 1796. Having married into the Robertson family, Sandbach became a full partner and rose to take over the whole enterprise.

He went on to become one of the biggest slave owners and most important mercantile figures in the UK.

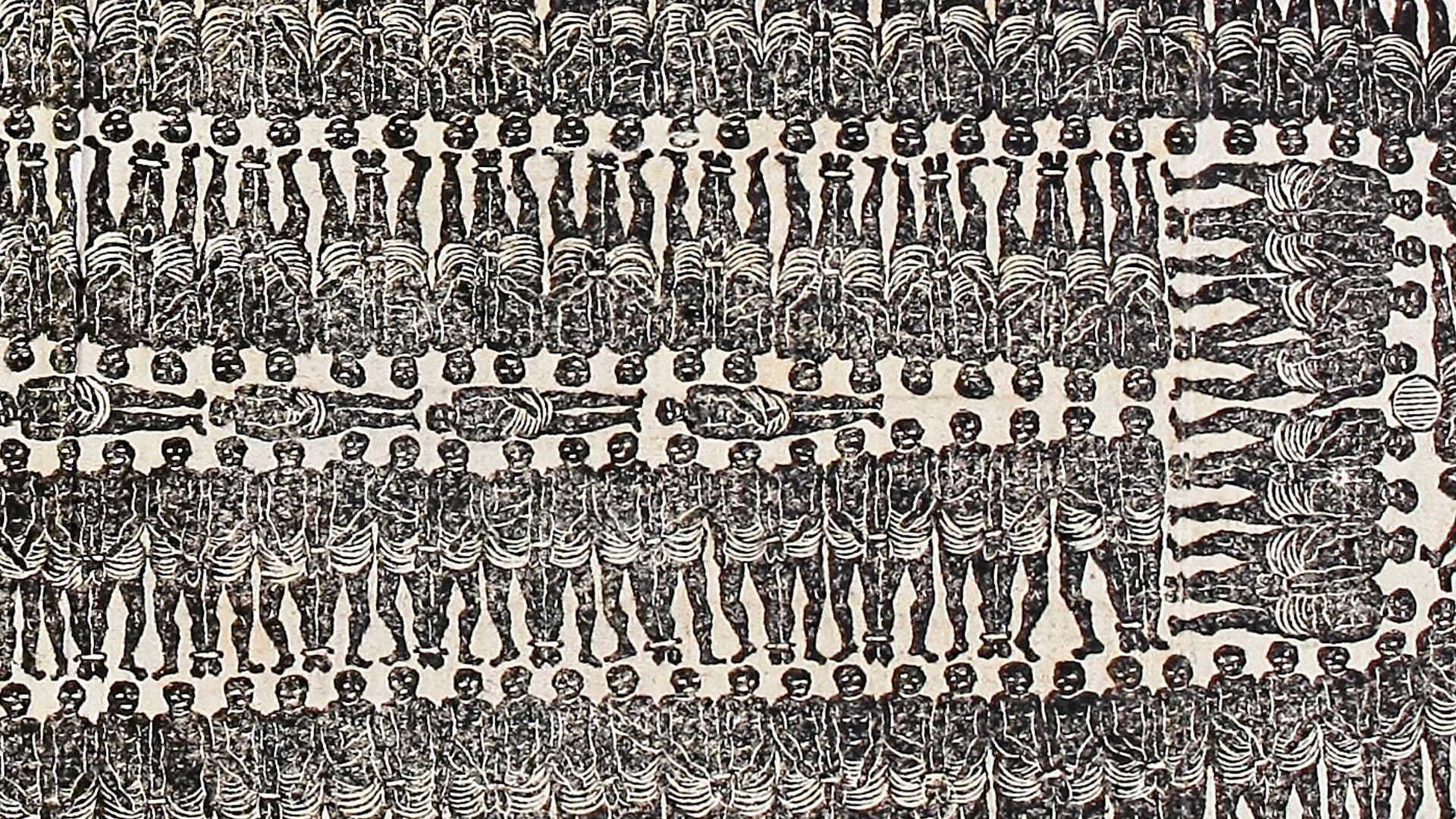

A document dated 31 August 1822 details the “negro account” for the buying and selling of slaves. It shows that Sandbach Tinne had lost £6,000 - apparently because of the death of company slaves.

At that time, an epidemic was ravaging Demerara and the surrounding areas, and it was the most vulnerable - the slaves - who were dying.

The documents reveal that in 1822 a fever or illness spread in what was then British Guiana, wiping out 5% of Georgetown’s population.

A letter describes death everywhere:

“This weather... has produced an epidemic which has been deeply felt amongst all classes and descriptions but has been chiefly fatal amongst the negros ...

The slaves may have been dying, but the writer's chief worry is the almost complete collapse of production on the plantation, and how profits are down nearly 75%:

“[It] has in one shape or another been so general that we may say for the last four or five weeks little or no work has been done on most estates.”

The conditions of the slaves were outlined by a missionary, Reverend John Smith, who visited Demerara in 1823. He describes them being overworked to absolute exhaustion, up to 20 hours a day on the plantations. Some, he says, were not permitted to sleep, but had to cut sugar cane through the night.

Looking back at my archive now, I try not to think about how the slaves must have suffered. It traumatises me to think about those who died.

Black men, women and children were categorised as profit and loss, along with animals. In reality the horses would have been treated with more respect.

The archive also provided the link I had been looking for.

It showed that the Woodlands plantation, where my family lived, was owned by Sandbach Tinne, and that from the 1830s onwards - like all their plantations - it was managed by Peter Miller Watson.

And this was the land inherited by Withyeline, and the rest of my family.

Everything pointed in the same direction - I was related in some way to Andrew Watson. There were Watsons still on the land, modern-day Watsons, family members related to me.

I felt a massive sense of validation - from starting off with just a picture of Andrew Watson and the family name, my instincts had been proved right. It gave me a sense of pride, in who I am and where I am from. I had a valid identity.

At first this felt great - I was connected to an icon of black history. But through him, I was also linked to a dark chapter of Britain's colonial past and the slave trade. The discovery was bitter-sweet.

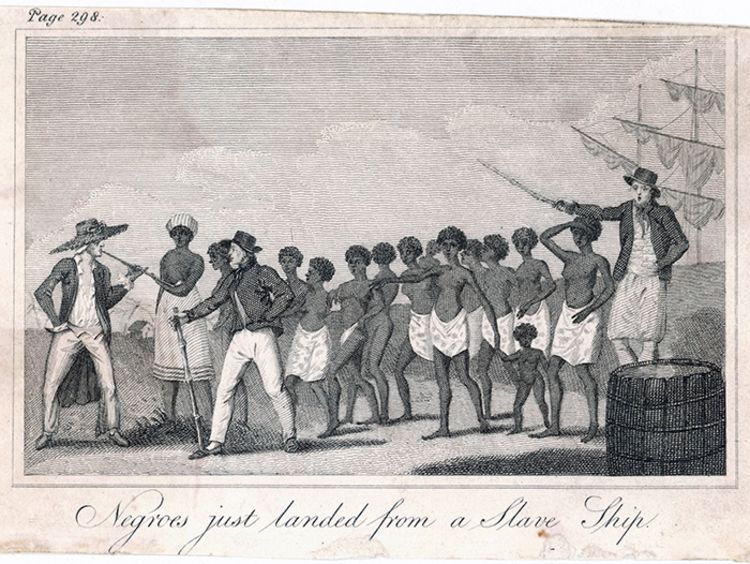

18th Century illustration of slaves arriving in Latin America

18th Century illustration of slaves arriving in Latin America

My ancestors were owned by slave masters. After years of brutality, their descendants inherited small pieces of their land and their name.

So many questions remain to be answered.

I want to return to Demerara and find the birth certificate of my grandfather, George Edward Watson.

It may well link him to Peter Miller Watson, or maybe one of his brothers, Henry or William, who were also in Demerara running the plantations.

I also remember something Withyeline said.

“The three white Scottish brothers - you’re related to them.”

The slave owners

My journey was bringing me full circle.

The wealth generated from the enslavement of my ancestors was brought by Samuel Sandbach to Liverpool - the city where I grew up and where I was always made to feel an outsider.

Sandbach rose to become what would now be known as a CEO for Sandbach Tinne & Co. He was one of the most visible partners, the largest joint shareholder of all of their operations in Demerara, Glasgow and Liverpool.

Off the back of thousands of slaves, numerous plantations and a fleet of ships, this son of a Cheshire farmer acquired a staggering amount of wealth.

In Liverpool Sandbach became a man of incredible influence. He was appointed the city’s mayor in 1831 - one of the most important people in one of the most important cities in the British Empire. From slaves, cotton and coffee, to sugar, rum and molasses, it all went through Liverpool.

A memorial to Samuel Sandbach and his wife Elizabeth at the family mausoleum in Llangernyw

A memorial to Samuel Sandbach and his wife Elizabeth at the family mausoleum in Llangernyw

He retired from Sandbach Tinne in 1833, passing on his shares in the company to his two sons. He was leaving the business he helped build in the same year as the Abolition of Slavery Act.

Under the terms of the act, £20m was paid out by the British government to slave owners in return for freeing their slaves (in fact this money, borrowed by the government, was not completely paid off until 2015).

Sandbach was a member of the West Indian Association of Liverpool, a group which lobbied to receive compensation for the loss of their slaves.

The association presented a silver salver to John Gladstone, MP, slave owner and father of the future prime minister, William Gladstone .

It was recognition of Gladstone’s role in negotiating generous terms with Parliament on their behalf.

The inscription on the salver reads:

“Presented to John Gladstone, Esquire, by the West India Association of Liverpool in testimony of the high sense they entertain of the value of his services so actively and beneficially employed in setting the conditions of the emancipation of the slaves in the West India colonies”

Silver salver presented to John Gladstone by the West Indian Association of Liverpool

Silver salver presented to John Gladstone by the West Indian Association of Liverpool

Incidentally, John Gladstone's second wife, Ann McKenzie Robertson, was also a cousin of Samuel Sandbach's wife Elizabeth Robertson.

The end of slavery did nothing to dent Sandbach’s fortune or reputation. He allowed his mansion to be used as accommodation for high court judges arriving from London to hear cases in the city.

By the mid-1840s Sandbach had acquired a significant stake in the recently founded Bank of Liverpool, becoming its deputy chairman, and overseeing the vast wealth he had built up.

The Bank of Liverpool grew and grew.

Eventually it bought Martins Bank in London in 1918, and took its name in 1928. By now it had hundreds of branches across the UK, quite a rise for a bank started by slave owners just decades before.

In 1969 Barclays Bank took over Martins Bank, by now the sixth largest clearing bank in the UK. The role people like Samuel Sandbach played in its growth is now long forgotten, but it shouldn’t be.

His legacy is still evident today. I see it all around Liverpool, in buildings built with money from the blood of my ancestors.

When I walk past the former Martins Bank Building on Water Street in the city centre, I see the opulence of the British Empire. It amazes me that it was the local Barclays HQ until 2009.

Martins Bank Building in Liverpool

Martins Bank Building in Liverpool

In the doorway, in sculpted stone panels, is King Neptune, lord of the waves, holding two young African slave boys. It’s a nod to the shipping lines and the exploited who formed the basis of the bank’s wealth. Above them is the grasshopper, the symbol of Martins Bank and to the side, the Liver bird, symbol of the Bank of Liverpool.

The hierarchy is not lost on me - the slaves at the bottom, in the middle the sea, the slave routes and the money at the top.

Reparations

Reparations

The chances are I am related to the slave owners and the slaves, just like the man who helped start this journey for me, Andrew Watson.

It's my belief that his mother was a free black woman, possibly the daughter of one of Peter Miller Watson's business colleagues in Demerara.

There were such black women in Guyana who were wealthy in their own right, usually the children of white merchants.

But many more women in Demerara did not have a choice about having sex with the men working for Sandbach Tinne, any more than they had a choice about working on the plantation, or being shipped from West Africa.

But the story of the slaves in Demerara isn’t over yet, and it won’t be until there has been restorative justice.

Slave owners were compensated after slavery was abolished in Britain in 1834. They were paid an estimated £17bn in today's money. The slaves got nothing.

That wealth flowed into British society.

Sandbach Tinne existed as a company until the 1970s. Samuel Sandbach was a founding shareholder in the Bank of Liverpool, which went on to become part of Barclays Bank.

Letter from Malik's archive addressed to Sandbach Tinne, Liverpool

Letter from Malik's archive addressed to Sandbach Tinne, Liverpool

Last year Glasgow University announced it would pay £20m in reparations to atone for its historical links to the slave trade.

The pub chain and brewer Greene King has said it too will be paying reparations in some form, along with the insurance market, Lloyds of London.

Caricom, the body representing 15 Caribbean nations, has called for meaningful reparations for the transatlantic slave trade. It’s a call that’s not going to go away.

(A Barclays spokesperson told the BBC, “The history of Barclays, like other institutions, is being examined following recent events. We can’t change what’s gone before us, only how we go forward. We are committed as a bank to do more to further foster our culture of inclusiveness, equality and diversity, for our colleagues, and the customers and clients we serve.”)

As for me, the journey that has taken me from Liverpool to Guyana and back again, will soon take me to the University of Cambridge.

The boy who left school - and care - without qualifications will soon be studying for a PhD, researching Sandbach Tinne and the role it played in the slave trade.

It started out as a family tree, but became a way of reasserting my dignity and my cultural identity.

My archive details the workings of one company, but this was just one part of a crime against humanity, which involved the exploitation of millions of people. It’s important that nobody forgets that.

This is a moment to understand what happened during the slave trade. Why were the slave owners allowed to treat my ancestors with such depravity, as less than human?

There needs to be recognition and accountability.

Organisations whose wealth originally derived from the barbaric trade in human flesh should be held accountable. There should be meaningful restitution for past wrongs - not just a public relations exercise.

Nearly 200 years have passed but the oppression is still here today. Racism is very much alive - just ask George Floyd’s family. So how can we heal?

If we don’t look into our past we cannot understand today. As Gil Scott-Heron once said to me, “If you don’t know where you come from, you won’t know where you are going. You have to study your history.”

This is mine.