The 2025 Women’s Rugby World Cup will kick off in what feels like a different world to the one that hosted the inaugural edition 34 years ago.

The history of the tournament tells a story of women persevering through resistance to play a sport they love, of the world waking up to elite athletes hidden among us and of Black Ferns breaking English hearts - over and over again.

THE BEGINNING

In the beginning, women had to do it for themselves.

As whispers of a possible global international women’s rugby tournament grew louder, England players were eager that it be hosted close to home to save on travel costs.

The logical solution? To organise it themselves.

Deborah Griffin, who recently became the first woman to be president of England’s Rugby Football Union, volunteered to take the lead. She was supported by her Richmond team-mates Alice Cooper, Sue Dorrington and Mary Forsyth.

Rugby’s global governing body - the International Rugby Board (IRB) - was not pleased.

It was organising a men’s World Cup for later that year and, concerned it might affect that tournament, refused to officially recognise the women’s equivalent.

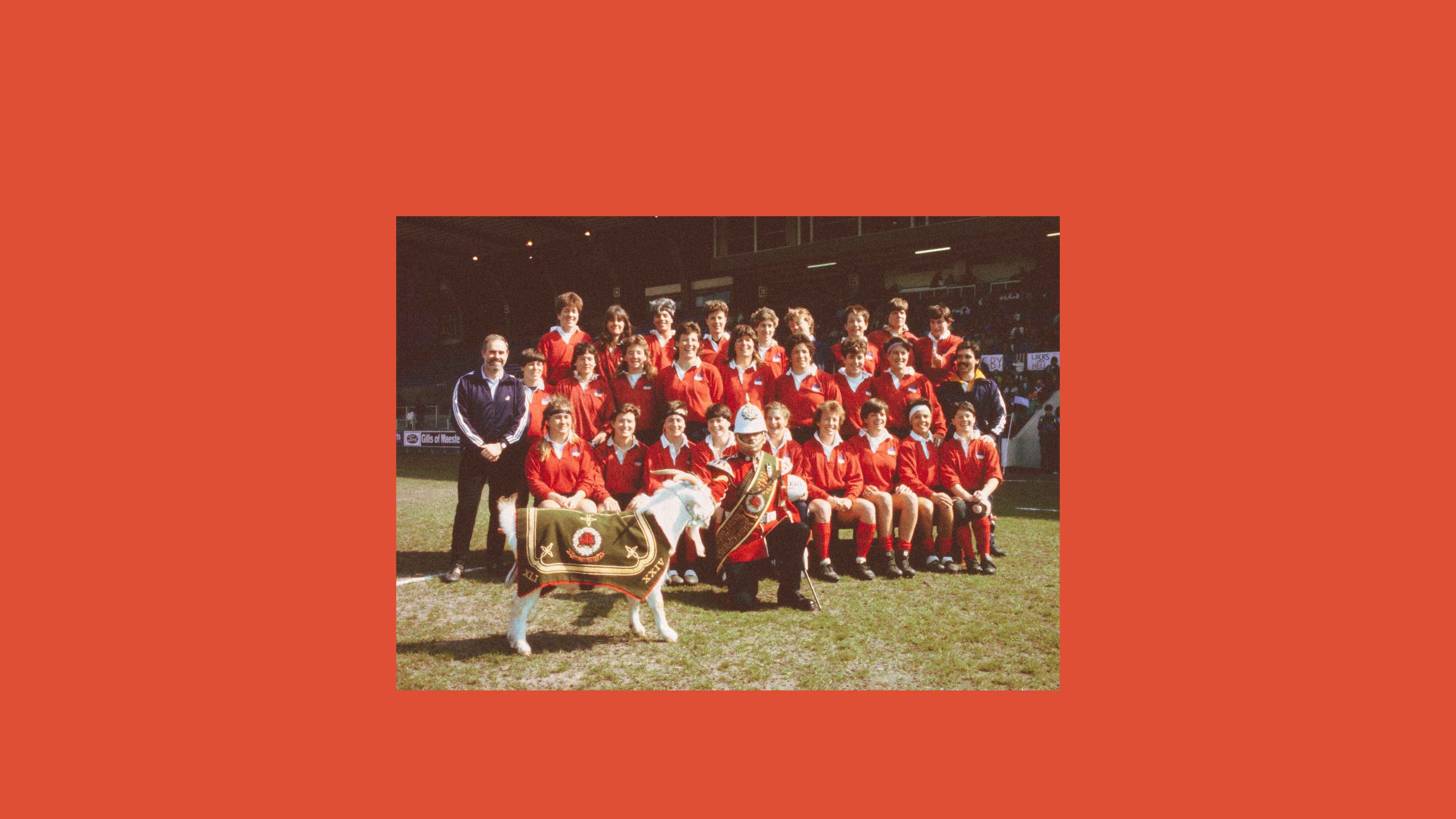

Griffin and her gang went ahead nevertheless, securing Cardiff as the host city. Chaos and joy ensued.

A Soviet Union team took part and, unable to leave their communist homeland with money, travelled with goods to trade which apparently ranged from caviar to Soviet champagne.

It is said that when they tried to sell vodka on the steps of Cardiff’s City Hall, Griffin was woken by customs officers at her door.

France had confirmed they would compete just minutes before the draw took place and New Zealand - then known as the ‘Gal Blacks’ - were embroiled in a debate about whether women should perform the Haka with a wide-legged stance.

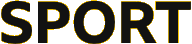

For some newspapers, women playing rugby was a novelty. A piece in the Sunday Mirror before the tournament began was headlined ‘Scrumptious’, with England players posing in evening gowns described as “no macho machine” and “supremely feminine”.

The players responded on the pitch and England, playing under their own women’s union co-founded by Griffin and so wearing a different rose on their shirts to the men’s team, flew into the final.

With the big game against the United States approaching, they found their hotel rooms had been double booked and had to sleep in sleeping bags on the floor of a conference room.

The United States, with “locks from hell” and “turbo props”, came out on top, winning 19-6 in front of around 3,000 fans.

Another World Cup was due to take place in 1994, brought forward by a year to avoid clashing with the men’s version.

It was left without a home after disagreements with the IRB led to the Netherlands pulling out as hosts three months before the tournament was due to start.

Scotland wing Sue Brodie and her team-mates had been training for their World Cup debut in Edinburgh and gathered at a pub in Leith after hearing the news.

Brodie convinced the others they could host the World Cup themselves, although they would call it a World Championships to appease the IRB.

“We thought, ‘let’s just invite the teams here and see what happens,’” Brodie told BBC Scotland News in 2024.

Players and staff had to cover travel and accommodation costs themselves. The organisers balanced full-time work or studies and families with training and, now, organising an international rugby tournament at short notice.

Spain dropped out at the last minute and a Scottish Universities team stepped in to fill their group.

Brodie and her team pulled it together with support from the Edinburgh rugby community, finishing second in their group to England, but losing 8-0 to Wales in the quarter-final.

The United States and England set up a repeat of the 1991 final - their fifth match in 18 days in a much more condensed tournament than the modern edition.

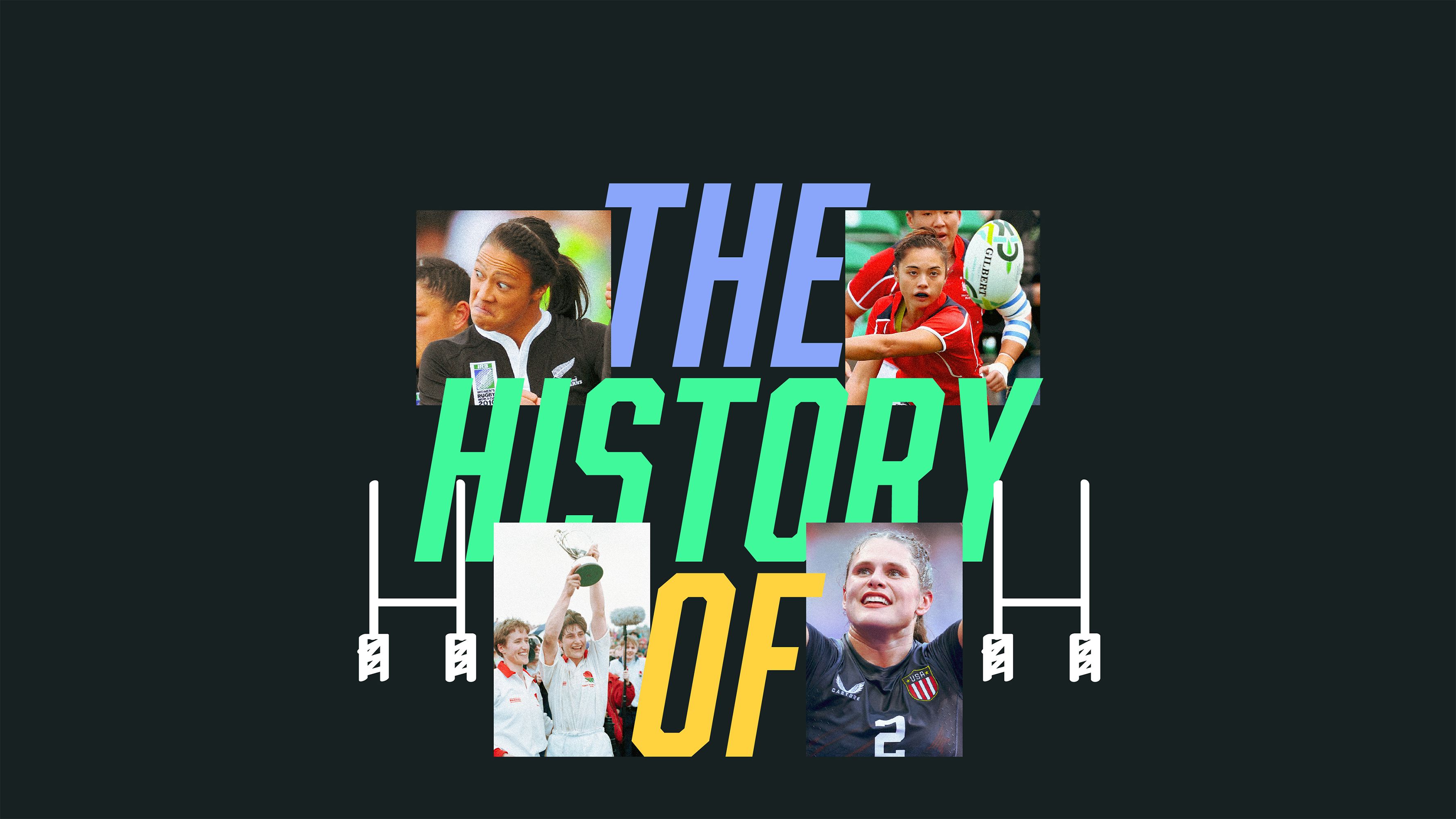

Karen Almond captained England at Raeburn Place and a crowd of around 5,000 flooded the pitch as her side claimed the World Cup with a 38-23 victory.

In a step forward in media coverage, highlights of the win were later shown on the BBC’s sports programme Grandstand.

MADE OFFICIAL

The increased public interest in the 1994 tournament urged the rugby establishment into action.

The IRB set out a development plan to integrate women’s rugby and the first World Cup officially sanctioned, and paid for, by the body was hosted in Amsterdam in 1998.

New Zealand had not made it to the 1994 World Cup because their union did not want them to play in an event that had not been sanctioned by the IRB. They more than made up for that absence in the tournaments that followed.

New Zealand scored 22 tries in an opening 134-6 win against Germany in 1998 and were relentless at World Cups for the next 16 years.

They went on to beat defending champions England 44-11 in the 1998 semi-final and the United States 44-12 in the final to win the tournament for the first time.

After presenting the trophy IRB chairman Vernon Pugh told the Sunday Times the tournament had been “yet another quantum leap”.

The 2002 World Cup was held in Barcelona. New Zealand once again dominated Germany in their opening game (117-0), but this time faced England in the final - a mere 13 days later.

The match was shown live in the middle of the night in New Zealand and around 8,000 fans came to watch at Barcelona’s Olympic Stadium.

England held a 9-6 lead thanks to Shelly Rae’s drop-goal, but those were the last points they would score and New Zealand pushed on for a 19-9 win.

It was the first of five finals between the two sides and the bitter feeling at full-time would become all too familiar for England.

The crowd for the final and television coverage had grown, but progress was still slow.

A report on the final in the Sunday Telegraph began with the line: “While the nation has been captivated by David Beckham's left foot, few will have noticed that England came tantalisingly close to winning the World Cup yesterday.”

Twelve teams, rather than 16, played in the 2006 World Cup in Canada in an attempt to have fewer one-sided games.

Around three weeks before the tournament began, a letter from England vice-captain Sue Day was published in the Observer.

“The England women's team fly out to the World Cup at the end of the month as second favourites,” she reminded readers and journalists.

“Each individual in the squad trains as a 'professional'. We have skill, determination and entertainment value to rival the men, and if you are reporting sport simply on its merits, then surely we would have seen news of our achievements.”

Day’s team lived up to her words, reaching another final against New Zealand - a match shown on Sky Sports. But the southern hemisphere side claimed a third title in a row with a 25-17 win.

GROWING

The game continued to grow: four countries expressed interest in hosting the 2010 tournament and England were successful in their bid.

The pool stages were held at Surrey Sports Park, with matches happening simultaneously across two pitches and 13 games broadcast live on Sky.

The Twickenham Stoop - in the shadow of the 80,000-seater stadium organisers are on track to fill for the 2025 final - hosted the semi-finals and final.

According to Ali Donnelly’s book Scrum Queens, New Zealand had played just six matches since the 2006 World Cup final and had to play their semi-final against France in white because their union had not provided enough black shirts for the tournament.

The inevitable New Zealand v England final came around. The hosts boasted then 20-year-old Emily Scarratt, touted as a future star of the game. The visitors were orchestrated by 45-year-old fly-half Anna Richards.

Three New Zealand players were sent to the sin-bin in the final and England came painfully close to victory in front of more than 13,000 fans.

The hosts tied the scores at 10-10 before a Kelly Brazier penalty secured yet another World Cup win for New Zealand.

In 2014, England threw everything at it - including the Twickenham gym. According to Scrum Queens, all the equipment was transported to France to make the side feel at home while they were training. Flanker Marlie Packer, in England's squad for 2025, played in her first 15-a-side World Cup.

It was Ireland who caused the biggest stir early on.

They inflicted New Zealand’s first World Cup defeat since 1991 in the pool stages, held at the French National Rugby Centre just south of Paris before the tournament moved into the city for the knockouts.

Amid concern that three New Zealand v England finals in a row had rendered the tournament predictable, the world order had been unsettled.

A 13-13 draw in England’s final pool game against Canada meant New Zealand would not feature in the knockout stages.

Ireland’s group stage heroics helped them to a first World Cup semi-final, which they lost 40-7 to England.

England would face pool opponents Canada in the final. The Canadians had some full-time players after professional contracts were introduced in preparation for rugby sevens’ inclusion at the 2016 Olympics.

The final came at the end of a 16-day tournament featuring 12 teams - the men’s 2011 World Cup had lasted just over six weeks with 20 teams involved. England played five Tests in 15 days - a schedule centre Scarratt described as “gruelling”.

Twenty years after their first World Cup victory, England claimed the trophy again with a 21-9 win against Canada at a sold-out 20,000-seater Stade Jean-Bouin.

England were still an amateur team - flanker Packer returned to her job as a plumber four days after the final.

After returning home, England were invited to meet then Prime Minister David Cameron at Downing Street and won Team of the Year at BBC Sports Personality of the Year.

Head coach Gary Street said: “This could be a tipping point for women’s rugby. We were hurt badly after the last World Cup and for a long time. But that’s gone away.”

PROFESSIONALISM

Following their victory, full-time contracts were given to 20 England players in 2014 to prepare for Team GB’s participation in the sevens tournament at the 2016 Olympics in Rio - and 16 15-a-side players were given contracts two years later.

Sevens events had led to organisers bringing the World Cup forward by a year to 2017 and that meant it landed at the end of a breakthrough summer for women’s sport in England.

At Wimbledon, Johanna Konta was the first British women’s singles semi-finalist since 1978. England won a home Cricket World Cup and the Lionesses reached the semi-finals of the Euros.

England’s rugby team were riding towards the World Cup hosted by Ireland on a wave of hope, but controversy hit as the Rugby Football Union announced 15-a-side contracts would end after the tournament so focus could return to the sevens format.

The pool games, held in Dublin, sold out, and extra capacity was added with the semi-finals and final held at Belfast’s Kingspan Stadium.

England progressed to the final and interest prompted the match to be moved from ITV4 to ITV1.

Viewers - and 17,115 fans at the stadium - were treated to a compelling match. England led 17-5 in the first half, but a hat-trick from New Zealand prop Toka Natua helped the four-time champions to a 41-32 win and a fifth title.

Change came more quickly then.

Later that year, a new domestic women’s league - Premier 15s - was created in England. In 2018, New Zealand were given part-time contracts and the following year 28 England players were awarded full-time deals.

Also in 2019, World Rugby - the IRB’s modern iteration - decided to drop ‘women’s’ and call both the men’s and women’s tournaments simply the Rugby World Cup. This decision was later reversed, adding ‘women’s’ back in for 2025 and adding ‘men’s’ from the 2027 edition.

The next Women’s World Cup was postponed because of the Covid-19 pandemic and took place in 2022.

“Women’s rugby is about to blow up,” New Zealand star Ruby Tui predicted pre-tournament as her country prepared to host. “Get on or move out of the way because it is coming.”

Four of the 12 teams had enough investment from their unions to be classed as professional: England, Wales, New Zealand and France - but the English and Wales investments did not stretch beyond economy flights to the southern hemisphere.

The tournament length was brought in line with the men’s World Cup, lasting 43 days to give players a minimum of five days’ rest between matches.

The opening day broke the attendance record for a women’s rugby matchday as 34,235 fans flocked to Eden Park - the previous record was set by the 20,000 fans at the 2014 World Cup in France.

All roads led to yet another New Zealand and England final. England had inflicted two record defeats on the Black Ferns in 2021 and entered the final on a 30-Test winning streak.

But those losses had prompted New Zealand’s union to action, bringing in two-time men’s World Cup-winning coach Wayne Smith to lead the side.

When facing England in a World Cup final, the Black Ferns always seem to find a way to win. This time was no different.

England lost wing Lydia Thompson to a red card in the 18th minute and held on valiantly to set themselves up a chance to snatch a late victory.

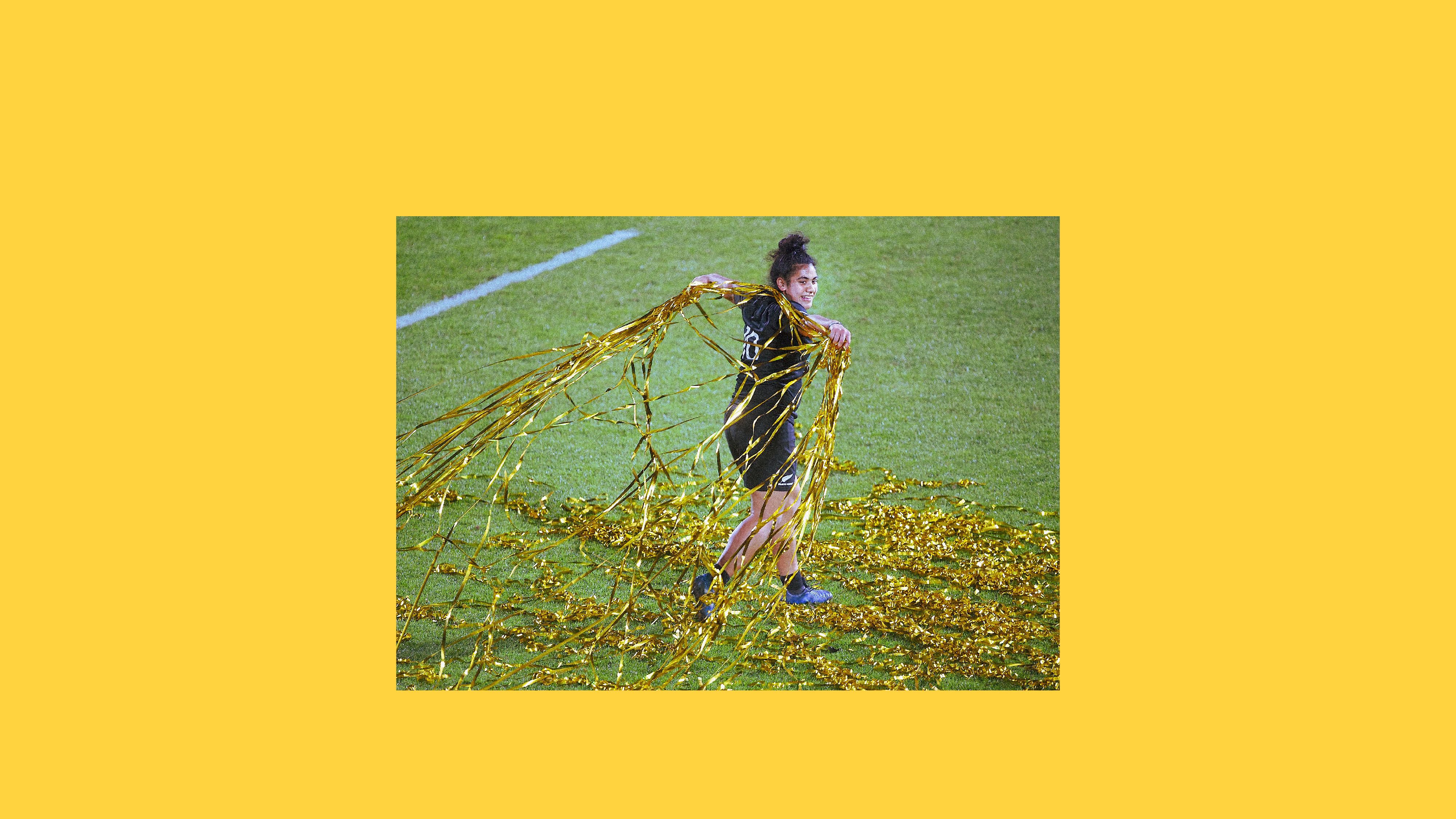

Their last-ditch line-out was stolen by the hosts, who claimed a 34-31 win and soaked in all the love of a 42,579-strong crowd as they celebrated a sixth World Cup title.

No-one had ever paid to watch the Black Ferns play in New Zealand before the 2022 World Cup. By the end, 40,000 fans at Eden Park were chanting their name.

The 2025 tournament has already shown signs of growth. Expanded back to 16 teams from 12, around 330,000 tickets have been sold so far.

Hosts and favourites England will start on a 27-match winning run that goes back to that last painful defeat against New Zealand in 2022.

New Zealand pulled out a performance when it counted most to create a fairytale finish on home soil.

England will be hoping to do the same in front of a sold-out Twickenham crowd on 27 September.

Credits

Written by Becky Grey

Sub-edited by Richard Dore

Graphics by Andy Dicks

Images by Getty Images