Tuam

Ireland's secret burial shame

It was a story of institutional inhumanity – which, at first, many found unbelievable.

Hundreds of babies and children, buried in an unmarked mass grave, at the site of an institution for unmarried mothers near the west coast of Ireland.

St Mary’s Home operated in Tuam, County Galway, from 1925 until 1961.

A religious order ran the institution, at a time of moral taboos when there was a social stigma around pregnancies outside of marriage.

It’s 11 years since a local amateur historian uncovered evidence of the scandal – and now, an excavation is beginning to try to identify the lost children.

We have spoken to the survivors, relatives and campaigners who shattered the secret.

The "Home"

PJ Haverty spent the first six years of his life in an institution that has come to define Ireland’s disturbing secrets.

But he was one of the lucky ones.

“I got out of there."

PJ’s early life was spent in St Mary’s Children Home, in Tuam.

For locals, it was simply called “the home”. But PJ – and other survivors - have another name for it.

“A home is a place where there is love and care,” he said.

“We were just locked up in there. I call it a prison.”

The institution is long gone now, - mostly demolished more than 50 years ago. All that’s left of the main part of the building is a six metre long wall of the Chapel and dining hall.

Most of the six-acre site of St Mary’s is now a housing estate, replete with a children’s playground, where young people play on slides and swings at a place where, for a time, mothers were separated from their babies - most often forever.

Nearby, is a patch of grass that has been turned into a simple memorial garden - beneath is where excavators will investigate what is believed to be a secret burial site for hundreds of children.

Visitors have left little shoes, cuddly toys and laminated poems to commemorate those whose remains will be exhumed.

In the early decades of the Irish state, founded in 1922, the Catholic Church held an immensely powerful position – and that meant those who fell outside the demanded norms of the Church, and society, faced huge social stigma.

One of those groups were women who fell pregnant outside marriage. They were often shamed by their community and shunned by their family, forced out of sight and into mother-and-baby homes.

PJ found out later that his mother was taken to St Mary’s by a priest, who told her she was no longer allowed into the church because she was a sinner.

A year later she was told to leave the home without PJ.

“You were dirt from the street, because you were born out of wedlock,” PJ said.

“It’s so sad that the likes of me and my mother had to be punished.”

PJ Haverty was one of 3,349 children who lived at the home during the course of its 36 years as a mother-and-baby institution.

He doesn’t have many memories of being in the institution itself. But he does remember his experience of going to school from there in the 1950s.

Those known as “home children” were ostracised.

“We had to go 10 minutes late and leave 10 minutes early, because they didn’t want us talking to the other kids,” PJ said.

“Even at break-time we weren’t allowed to play with them – we were cordoned off."

PJ was eventually fostered as a six-year-old by parents who gave him a loving upbringing – he attributed their compassion and care to them having worked in England.

“They were never dictated to by the Church as much as Ireland was,” he said.

But the stigma of being a “home child” stayed with him for decades – he poignantly recounts how “life became very tough” when he was in his late teens.

His foster mother encouraged him to go out to dances. But when PJ went, he was subjected to cruel jokes and abuse because of his background.

The girls he spoke to dismissed him, the boys ridiculed him.

He found the abuse “shocking, very hurtful”.

“I used to run home and cry myself to sleep. At one stage I considered taking my own life.”

It was around the same time that PJ’s foster mother implored a local social worker to help him find his birth mother.

The social worker said she could not “say a word”, but was persuaded to leave a note with an address on the table. Years later, he went to the place his mother was originally from.

“Eventually I found out that I had an aunt. So I went to the house and knocked on the door.

“She got a fright and said she recognised me right away.”

A few weeks later, PJ received a letter from his mother, Eileen, who was living in England.

She had married but had not had any more children.

He drove to London to meet her, where he finally learned how he came to be in the home and that "she did her best to get me out of there" and never wanted to give him up.

After they were separated when he was a one-year-old, she got a job as a cleaner at the hospital in Tuam.

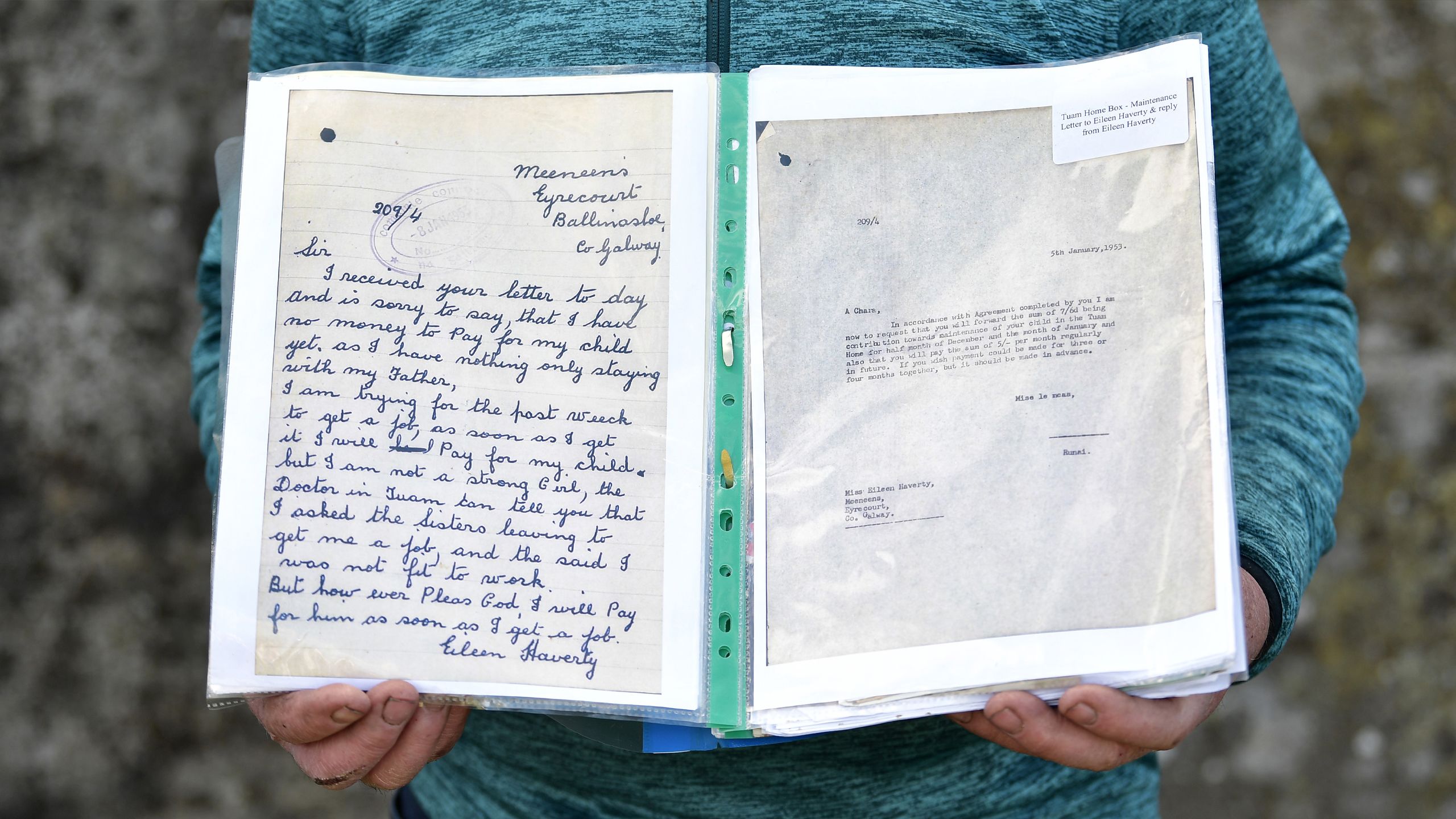

She had to pay five shillings every month for PJ’s upkeep in the institution. It was a place she went back to every week, to ask to take him out.

According to PJ, the nuns wouldn’t allow it.

PJ even found out they had met once, briefly, during his childhood.

He remembers seeing a car with an English number plate arriving at his foster family’s farm, when he was about nine.

Two women were in the vehicle - one of them wound down the window and asked him where his foster parents lived.

“She kept staring at me and smiling, and I thought this was very unusual. What was she doing it for?”

The woman was Eileen.

According to PJ, she went to see a priest during that visit to Tuam, in the hope she could bring her son back to London where she had settled.

“The priest said it would only confuse me, so she was to leave me where I was. Her heart was broken.”

PJ’s story is one of information drip-feed – a constant battle with authorities, officials and the Irish state for access to his own past - and complex emotions, which he recalls with searing clarity.

As he struggled with a system, which aimed to preserve secrecy and deepen separation, he didn’t know about a deathly further dimension to the institutional inhumanity.

He found out about it, along with the rest of the world, in 2014.

“Never in my wildest dreams did I believe that so many could die in a home like that, and to think they were dumped in a tank.

“I just couldn’t get my head around it.”

The Historian

Catherine Corless thought it would be a “simple, run-of-the-mill kind of thing” when she began a local history course in 2005.

She was interested in family history, and the many ruined old buildings that peppered the countryside around Tuam. The year-long course would give her the skills to dive into that research.

Instead, when Catherine’s interest turned to the local children’s home with a view to writing an essay for a local historical journal.

She ended up uncovering an internationally-recognised scandal and became the person who prevented hundreds of babies and children being lost to history.

"When I started out, I had no idea what I was going to find," she said.

“It was the kind of hush-hush tones in people, I knew something wasn’t right.”

We are talking around her kitchen table, which is covered with newspaper cuttings, records, notes and maps from years of research and campaigning.

She lives at her farm, with her husband Aidan, a few miles from the Tuam area where she was born, raised and went to school - and her memories of the “home children” mirrors those of PJ Haverty.

“I remember we weren’t allowed to mix with them,” she said, “to the extent that they came in later in the morning, and left earlier in the evening.”

About 50 years later, she began work on an essay for an annual publication - the Journal of the Old Tuam Society.

Recalling the home, ran by an order of nuns called the Bon Secours Sisters, she decided the institution would be her subject.

But straight away, she was surprised to find obstacles.

The local library had no information. When she asked people in the area about the home, her inquiries were treated with suspicion.

She asked various organisations for information - the Bon Secours Sisters; Galway County Council; local leaders in the Catholic Church - but was told they had none to share.

“Nobody was helping and nobody had any records,” she said.

Finally, she found someone who could tell her something - the caretaker of a cemetery near the site, who brought her to the housing estate where the institution once stood.

At the side of the playground, there was a square of lawn, with a grotto – a small shrine centred on a statue of Mary.

This small patch of grass is now known around the world as the image of the Tuam mass children’s grave.

The cemetery caretaker told her the story of two boys, about nine years old, who had been playing there in the mid-1970s after the home was demolished.

They saw a broken concrete slab in a bushy area and pulled it up to reveal a hole.

Inside they saw bones.

The authorities were told and the spot was covered up.

Most people were led to believe the remains were from the Irish famine in the 1840s – a decade of appalling starvation, when an estimated one million people died.

But, for Catherine it still "wasn't adding up".

The home had originally been a workhouse during the famine, which provided shelter to those in need - but Catherine knew the people who died at the workhouse had been buried respectfully, in coffins, in a field half a mile away. There was a monument marking the place.

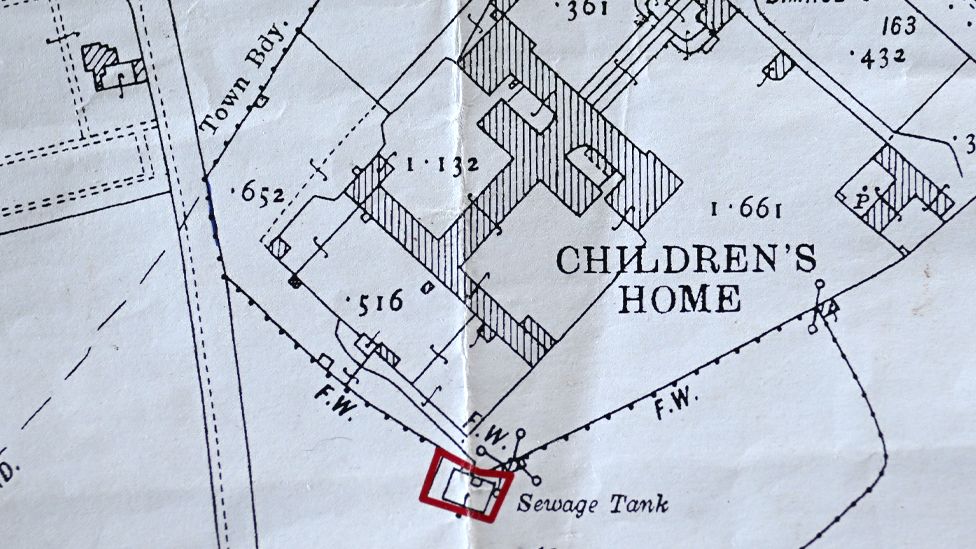

A significant moment came when she compared old maps of the home.

She puts one of them, from 1929, on the tabletop in her kitchen.

It features an H-shaped shaded diagram marked “Children’s Home” – and just outside it, a smaller, rectangular structure, which has the words “sewage tank” printed alongside.

This was exactly the place where the boys had seen the bones

Catherine places a map from the 1970s on top of the one from 1929, which shows the layout of the housing development built after the institution was knocked down.

When the maps are placed exactly on top of one another, the new map shows the spot where the “sewage tank” was shaded in yellow – and “burial ground” is handwritten beside it.

Aerial photography of the site today shows how the maps match up to the original boundary wall, and the memorial garden.

Catherine had read in newspaper archives the sewage tank became defunct in 1937, when the institution was joined to the town’s sewerage system.

The map seemed to indicate that this area had indeed become some kind of burial ground - but for who?

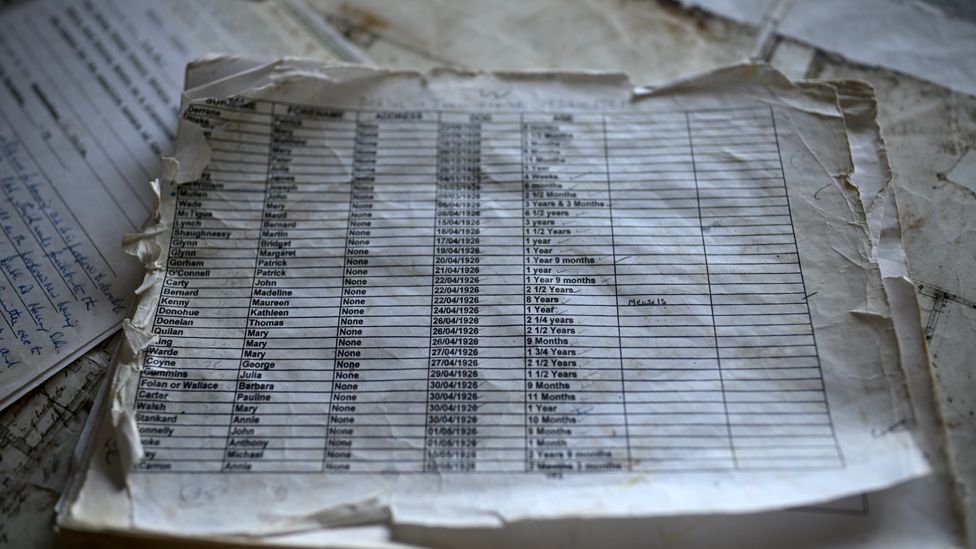

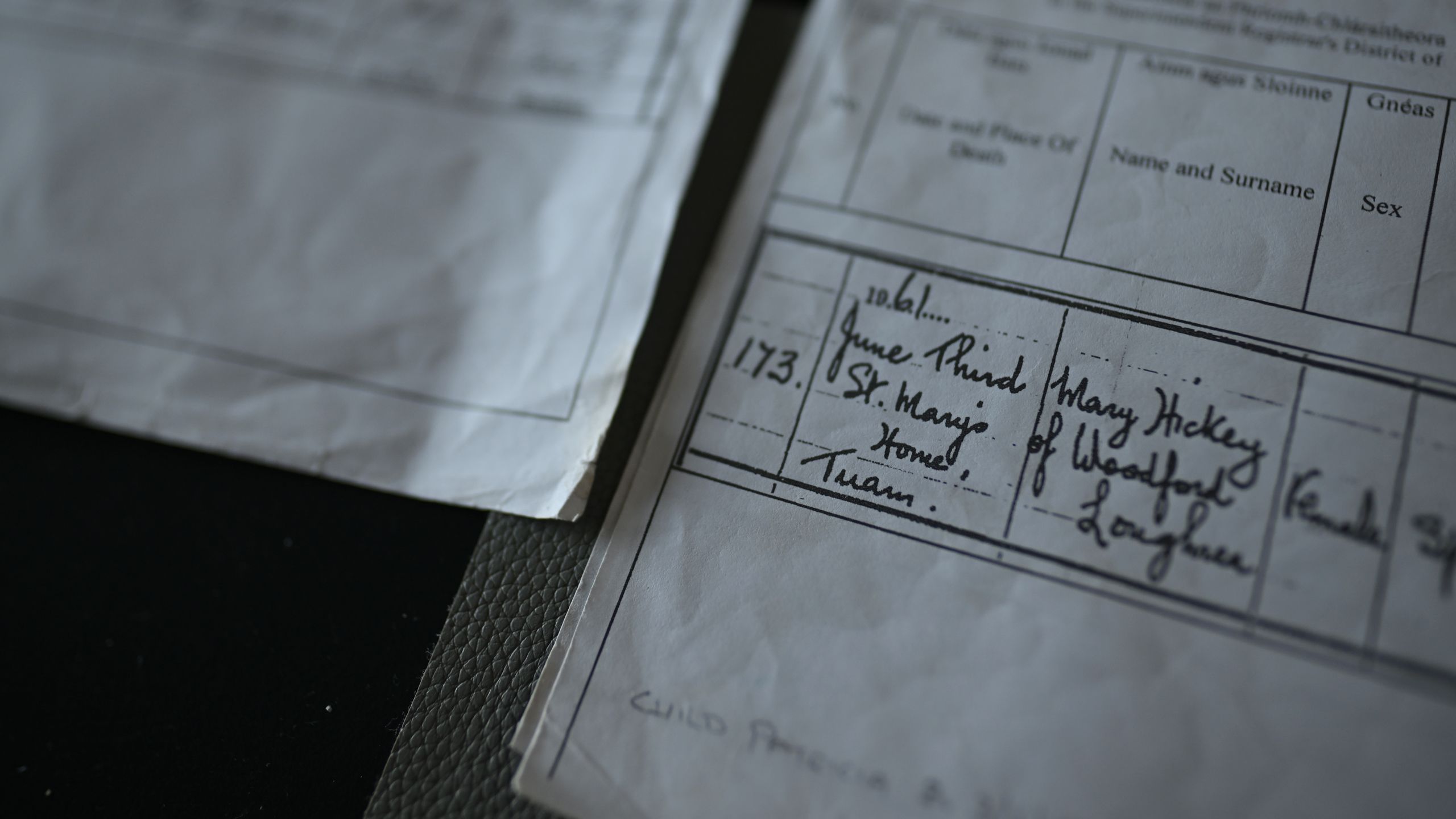

So Catherine called the registration office for births, deaths and marriages in Galway.

“I told them I needed the names and dates of deaths of all the children who died in the home.”

A member of staff phoned Catherine a fortnight later – did she really want all the records?

Catherine had expected “20 or 30”.

There were hundreds.

The clerk agreed to print out a list, which contained names, date of death and cause of death.

Catherine counted each one – the total was 796.

The first, from 1925, recorded the death of Patrick Derrane – aged five months.

The last to die Mary Carty in 1960. She was the same age.

Among the recorded causes of death were measles, whooping cough, influenza, tuberculosis and bronchitis.

Catherine was “utterly shocked”. She pictured her own grandchildren as she contemplated those young lives.

There was no obvious record of where these children were buried and her suspicion was beginning to rise - but she had to check burial records. Perhaps these 796 children were buried somewhere other than the home?

She asked the cemetery caretaker, who had been so helpful before, to check his graveyard. They sat in his van and looked up the register, while the rain poured on the graves outside.

None of the 796 were there or in many of the cemetery records she checked in Galway and neighbouring County Mayo.

So there were nearly 800 death certificates and zero burial records from children who died at the home. Catherine now believed those babies had been buried in an unmarked grave at the institution, and potentially in a defunct sewage tank.

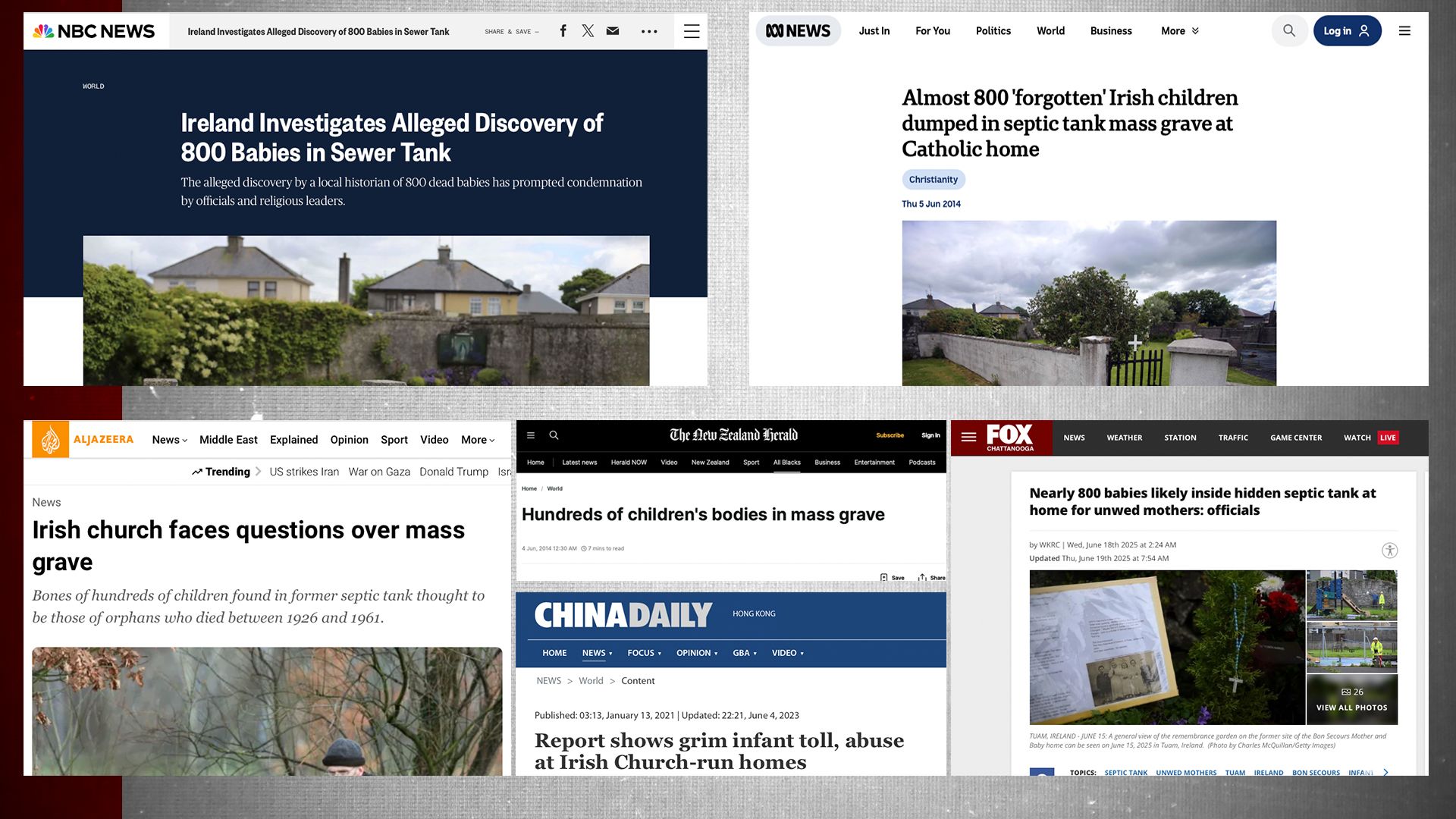

Those findings formed a major part of the first big media story about the Tuam children, an article by Alison O’Reilly in the Irish Mail on Sunday.

It triggered follow-ups from newspapers, websites and broadcasters from the US to New Zealand.

Locally, however, Catherine faced hostility and scepticism.

How could this momentous Irish scandal be covered up for so long? And how could it have been uncovered by an amateur historian, no less, who’d just completed a part-time course?

“People weren’t believing me,” Catherine said. Some local businessmen accused her of being out “for a bit of glory”.

One email to a TV documentary-maker from a public relations agency hired by the Bon Secours Sisters, appeared to sum up the attitude: “If you come here, you’ll find no mass grave, no evidence that children were so buried, and a local police force casting their eyes to heaven and saying: ‘yeah, a few bones were found – but this was an area where Famine victims were buried. So?'”

There were others who did believe Catherine. One woman had even seen the evidence with her own eyes.

Mary Moriarty heard what was said about Catherine Corless in the town – that she was “mad”, that people shouldn’t talk to her.

Mary knew differently.

“I said, she’s not mad – there are babies down that hole."

Sadly, Mary died not long after we interviewed her - her family have kindly agreed to allow what she told us to be published and broadcast.

In the mid-1970s, she lived in one of the houses near the site of the institution.

“Two women came in and said they saw a young fella, with a skull on a stick,” she recounted.

Mary and her neighbours asked the child where he had found the skull. He showed them some shrubbery and Mary went to look, telling the other women she saw a slope in front of her.

“As I said the words I fell in a hole. The women got me by my shoulders to pull me up. But my feet were on something hard, I was still standing.”

She saw there was a shaft of light breaking through to the strange surroundings in which she had found herself.

“I said, wait a minute – let’s see what’s down here.

“That’s when I saw the little bundles.”

She looked around her kitchen for something to help explain the size of each “bundle”, saying they tended to be about the same dimensions as a “juice bottle”.

I asked her if she saw dozens – and she replied: “Hundreds.”

She described how they appeared to be “stacked”.

“First I thought they were stairs, going backwards and upwards. But it wasn’t that. As they went up they also went back – so they wouldn’t all fall down.

“They were packed one after the other, in rows up to the ceiling.

“They were rolled up in cloths, which had gone black from wet and rot in a damp place.”

Some time later, her second son was born in the maternity hospital in Tuam – he was brought to her by the nuns who worked there “in all these bundles of clothes”, just like those she had seen in that hole.

“That’s when I copped on – what I had seen after I fell down that hole were babies.”

Catherine Corless’s discovery – and the subsequent campaign – sparked a new level of interest in the network of mother-and-baby institutions across Ireland.

It led to the Irish government setting up an inquiry, known as a commission of investigation.

In 2017, the commission confirmed it had found “significant quantities of human remains” in a test excavation of the site.

Radiocarbon dating suggested they were from the time of the mother-and-baby home and not the famine.

The “age-at-death range” was from about 35 foetal weeks to two or three years.

The Excavation

On Monday 16 June, the workers moved onto the site.

One digger and hundreds of temporary metal fences were brought to the playground at the housing estate where the home once stood. The 2.5m high hoardings sealed the site off from the outside world, treating it exactly the same as a police investigation.

Workers were getting ready to excavate the playground and grassy area of the memorial garden, to finally lift up the earth and discover the full extent of what lies beneath.

The work is expected to take about two years and, as a project relating to the recovery of young people’s bodies, is thought to be unprecedented – not just in Ireland, but anywhere.

Daniel MacSweeney

Daniel MacSweeney

“It’s a very challenging process – really a world first,” said Daniel MacSweeney, the director of authorised intervention at Tuam – the head of the excavation.

He is in a position to make that claim, given he worked with the International Committee of the Red Cross for 16 years, helping to find missing bodies from conflict zones such as Afghanistan and the Caucasus region.

Over the last decade, the opposition faced by Catherine Corless has faded to something more akin to reluctant acceptance, particularly after the 2017 test excavation confirmed what she had found.

“Up until that point, I couldn’t exactly prove they were the home babies,” she said.

“All I had was evidence pointing to it, and that there couldn’t possibly be any other answer.

“But that day, I got the validation.”

PJ said the achievement of getting a full excavation – a necessity, in his view, so those children can have a “dignified burial” – is Catherine’s.

“She has fought everybody. There were walls and everything put up against her, bricks put up against her but nothing was going to stop her,” he said.

The scale, detail and challenges of the scientific work at Tuam are extraordinary.

Daniel explained that the remains are “co-mingled” – in other words, individual skeletons have broken down, and bones from different children have been mixed together.

The body’s largest bone is the femur – the thigh bone.

An infant’s femur is only the size of an adult’s finger.

“They’re absolutely tiny,” he said.

“We need to recover the remains very, very carefully, to maximise the possibility of identification.”

Archives and files from the institution will be reviewed. DNA samples have so far been taken from 15 relatives and about 35 others have come forward. There will be a public information campaign to encourage others to do so.

Daniel said the difficulty of identifying the remains “can’t be underestimated”.

At any one time, there will be between 20 and 30 people working on the site.

But despite the expected two-year timeframe, wider work is expected to continue for some time after that.

“The length of the analysis phase will depend on the volume and complexity of the remains that we find.”

For however long the excavation takes, there are people who will be waiting for news – hoping to hear about sisters, brothers, uncles, aunts and cousins they never had the chance to meet.

The Families

Anna Corrigan long had a notion she might not have been an only child.

“I didn’t know if it was a dream, if it was my imagination, or if I actually heard something,” she said.

“I always had this thing in my mind – that my mother and her brother were in the kitchen and were having a row.

“My uncle asked me if I knew my mother had two children. My mother told him to shut up, and told me to go out and play."

Anna, who lives in Dublin, grew up without knowing about any siblings.

In 2012, she was researching her family history and asked the children’s charity Barnardo’s to look for records linked to her mother, who had died in 2001.

She points to the corner of her kitchen, where she was standing when she received the phone call that changed her life.

The charity worker said she had information for Anna, but it wasn’t “protocol” to give it to her in a call.

“I said, please tell me, I’m old enough.”

It was just before Christmas. Anna was in her late fifties.

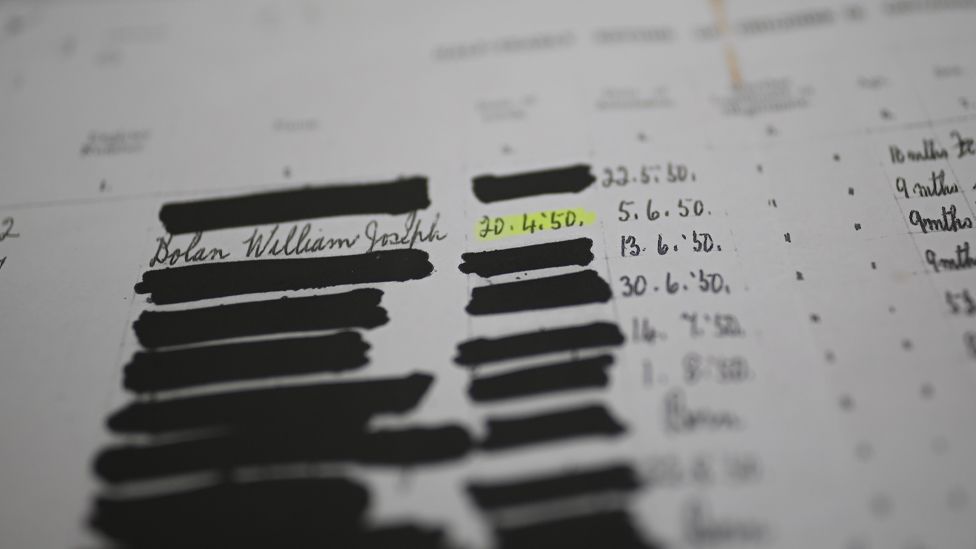

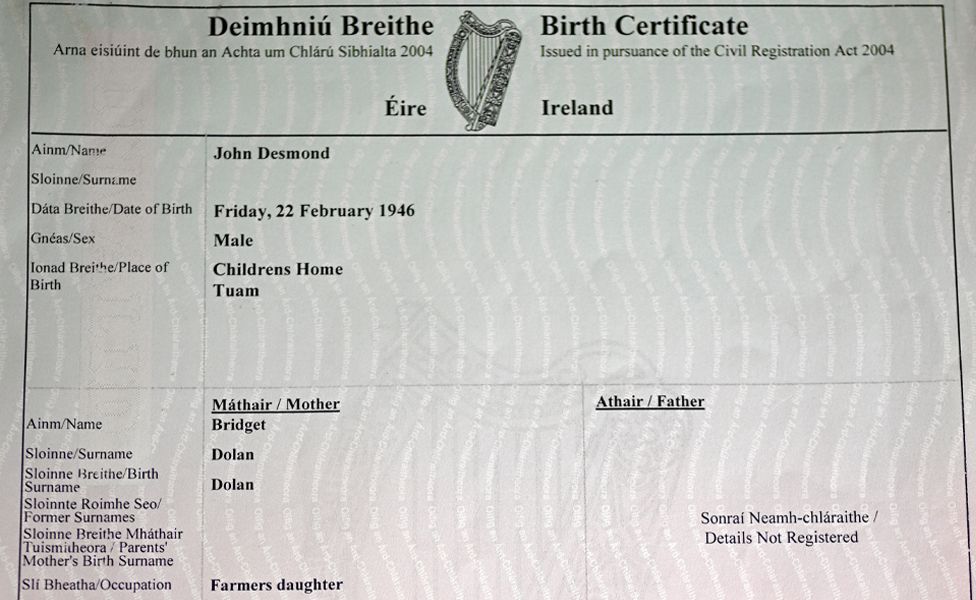

“The lady said, your mother gave birth to a boy called John Desmond, in 1946 – and she had a second child, named William Joseph, who was born in 1950.”

The days afterwards were “surreal”. She went to an office to see the paperwork and was given a death certificate for John, but was told William's death was not registered.

“They said that was strange,” Anna remembers.

So began a quest for answers.

“When I get something between my teeth I’m like a dog with a bone. I won’t let this go. That was the start of it.”

She has boxes of files – letters, replies, official documents – that she has gathered over 13 years of campaigning.

Bridget Dolan, Anna's mother, was one of more than 2,000 women and girls who lived at the home for a time.

She is recorded as John and William’s mother on their birth certificates. The columns for information about their father are blank.

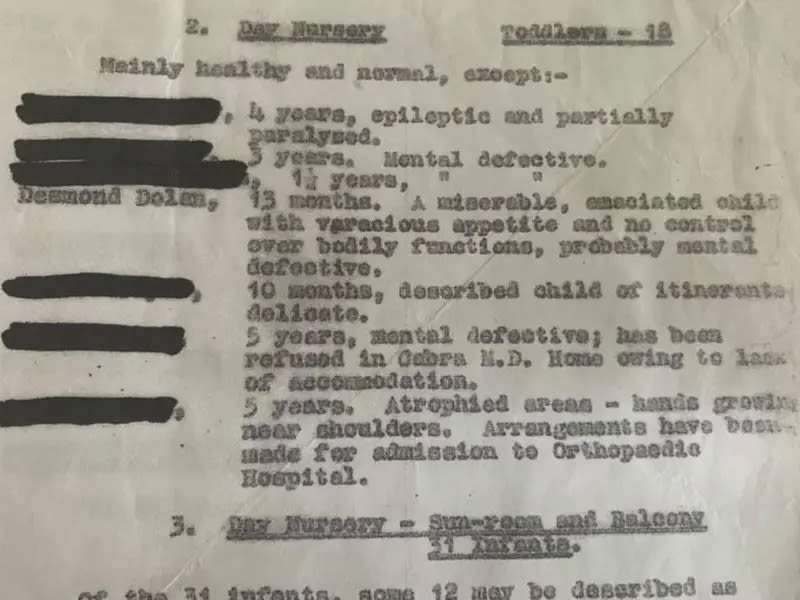

John’s death certificate officially registers that he died at the age of 16 months. Anna points to what is entered under cause of death – “congenital idiot” and “measles”.

She wonders aloud how anyone could have used that description for a child.

She obtained an inspection report from 1947, which had some more details about John.

“He was born normal and healthy, almost nine pounds in weight," she said.

“By the time he’s 13 months old, he’s emaciated with a voracious appetite, and has no control over bodily functions.

"Then he’s dead three months later.”

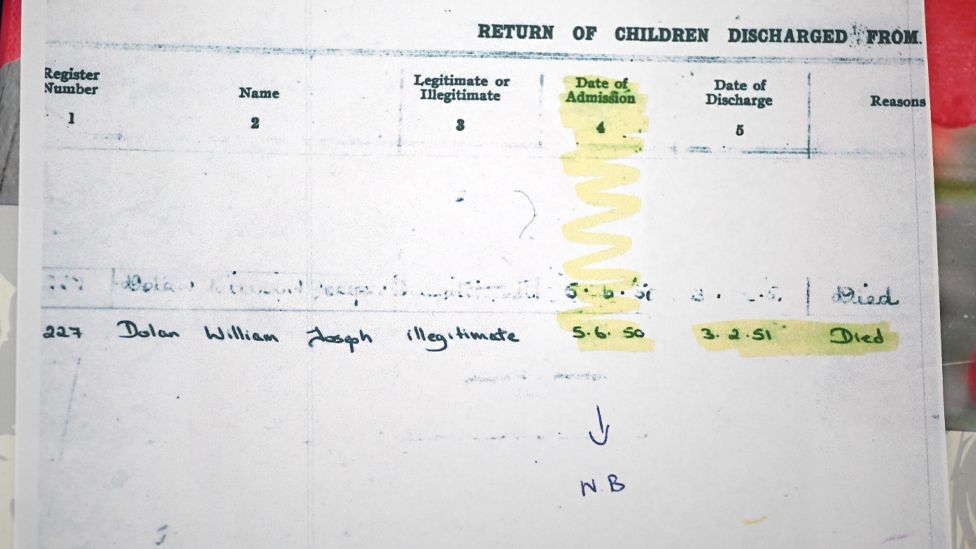

An entry from the institution's “discharges” ledger says William died in 1951.

But the absence of a death certificate raises more big questions for Anna – as does the fact that the dates of birth for William and her mother are erroneously recorded in some paperwork.

She has made statements about both of her brothers’ cases to the Irish police – An Garda Síochána.

Anna reported William as a missing person in 2013. The following year, she spoke to officers about John’s death.

“I contended that he died of neglect and malnutrition. The nuns were being paid for his care. There was a doctor in situ.

“When my mother left the home, she sent back five shillings a month for his upkeep. So how did it come to this?”

Anna, who set up the Tuam Babies Family Group, to enable survivors and relatives to help each other, said she's glad the excavation is happening but also feels cynical - she has already faced much "obstruction, obfuscation and prevarication".

She points to a number of occasions in the past when she believes the truth should have been acknowledged – even as far back as the 1970s, when the authorities were notified about what the two boys and Mary Moriarty had seen at the site.

Anna also has a letter from the Bon Secours Sisters from 2013, in which they told her there was a “good possibility” John was buried in a “general grave” at the institution.

It was a year later that the Tuam mass burials came to global attention with Anna’s family story featuring heavily in the media revelations.

She's frustrated at how long it took to pass legislation to enable the full excavation of the site, given the existence of children’s remains was confirmed in 2017.

She also questions why there hasn’t been a criminal inquiry, and inquests into the deaths.

“I can’t be jumping for joy at this stage, having tried to push it all along, given it could have been done at so many stages in the past.”

For Sara Niland, one of Anna's two daughters, however, there is nothing but pride.

“She took on a mammoth task and she never faltered.

“She stayed true to her values – it was always about the children and it was always about justice.”

The Future

It’s 64 years since the institution at Tuam closed, and 11 years since the full horror of what happened there came to widespread attention.

The unparalleled operation to recover and identify the remains from site, dubbed “a chamber of horrors” by then Taoiseach (Irish prime minister) Enda Kenny in 2017, has been campaigned for, legislated for and is now under way.

Everyone hopes that the children will now be given the dignity they were denied in their short lives.

For Catherine Corless, the historian who has made history herself, the fact the exhumation is going ahead is “beyond my wildest dreams”.

She knows Daniel MacSweeney’s team has “an extremely hard job”. And she knows how long the road has been to get this far.

“But for the media, I doubt that any of this would have come to fruition, because there was so much opposition. People didn’t want to talk about it, and wanted to leave it in the past."

The late Mary Moriarty, who did so much to help the campaign, said the babies she saw wrapped in bundles half a century ago should be “taken up”.

“Some think it shouldn’t be done. But what if you had any of your family in there? It’s an awful, sad situation. They should have a proper funeral, and be put in a graveyard.”

The Bon Secours Sisters, who ran the institution, apologised after the commission of investigation published its full findings, saying: "We did not live up to our Christianity."

The apology acknowledged the sisters “were part of the system in which they [women and children] suffered hardship, loneliness, and terrible hurt” and that "infants and children who died at the Home were buried in a disrespectful and unacceptable way".

"For all that, we are deeply sorry," they added.

The organisation is making a contribution of about €13m (£11.1m) to a state compensation scheme for survivors of mother-and-baby institutions.

It is also giving another €2.5m (£2.14m) towards the costs of the excavation.

Galway County Council, which owned the institution, apologised for its role saying: “We acknowledge the sad and painful truth, the personal impact and heavy burden carried by survivors and humbly acknowledge our failings.”

It also accepted it had failed to ensure that mothers and children “were afforded the dignity of an appropriate and respectful resting place”.

The leader of the Catholic Church in Ireland, Archbishop Eamon Martin, said he accepted “the Church was clearly part of that culture in which people were frequently stigmatized, judged and rejected” and unreservedly apologised "to the survivors and all those who are personally impacted".

Relatives and survivors generally say that no action or apology will ever make up for the institutional inhumanity and unspeakable cruelty.

Anna Corrigan knows her brothers may never be found.

“There’s a possibility that in 2027, 15 years on, I could be back where I started – with still no indication that my brothers are actually dead, that they could be walking around somewhere in some country, having been illegally adopted.”

But if she does receive news of a DNA match, she plans to bury the remains with her mother.

“It’ll be closure, that I can put on her tombstone: ‘Pre-deceased by her sons John and William.' I can’t put that on now because I don’t know whether they’re dead or not.”

She added: “Will we find all the children at Tuam? I don’t know.

“The children who don’t have someone come forward will at least have a dignified burial in a graveyard. We can right that part of the wrong.”

PJ Haverty – “one of the lucky ones” who survived– reflects that bringing the truth to light has sometimes felt like being “up against the superpowers”.

He is “absolutely delighted” the exhumation is getting under way.

“If they can’t identify who they were, they can at least have a headstone with their names on it, so people can leave a flower or say a prayer.

“These were little babies who couldn’t talk, they could only cry. How could you leave them there?

“Now they’re being recognised – they’re not just dumped garbage.”

Credits:

Author:

Chris Page

Editors:

Ciarán McCauley, Judith Cummings

Production:

Peter Hamill

Photography:

Charles McQuillan, Niall Gallagher

Archive Photographs:

Getty Images, Press Association, Reuters, Tuam Home Graveyard Committee