Secret Identities

“I don’t know who I am…

if you’ve ever made a jigsaw and you’ve got one piece missing, that’s how I feel.”

John Tuthill never knew his biological parents and the circumstances of his birth in Dublin 44 years ago remain a mystery.

Adopted as a baby in 1979, he has little idea about his original identity, despite a frustrating 13-year search.

Due to the complexities of adoption rules in the Republic of Ireland, John has an adoption certificate but no birth certificate.

Until now, Irish-born adoptees had no automatic right to the personal data they need to access their birth certificates – even their own name and their biological parents’ names could be kept from them.

It is a painful legacy from a recent period in modern Irish history when having a baby outside marriage was seen by many as shameful and socially unacceptable.

Due to the stigma, thousands of children born to single mothers ended up in the adoption system, where their names were changed and links to their birth families severed.

Claire McGettrick is an adoptee and a prominent campaigner

Claire McGettrick is an adoptee and a prominent campaigner

“Our identities were taken away from us. They were hidden from us to facilitate closed, secret adoption,” says Claire McGettrick.

Named Lorraine Hughes at birth, and adopted in 1973, Ms McGettrick is now one of Ireland’s most influential adoption rights campaigners.

She is also a co-director of the Clann Project, which carries out research into how unmarried mothers and their children were treated in 20th Century Ireland.

She says it is discriminatory to deny adoptees access to personal information that is routinely available to everyone else from the General Register Office.

“Birth certificates are public records, they have been over the past 150 years here in Ireland,” she explains.

“No other citizen has to jump through any hoops other than walking in and asking for their birth certificate.”

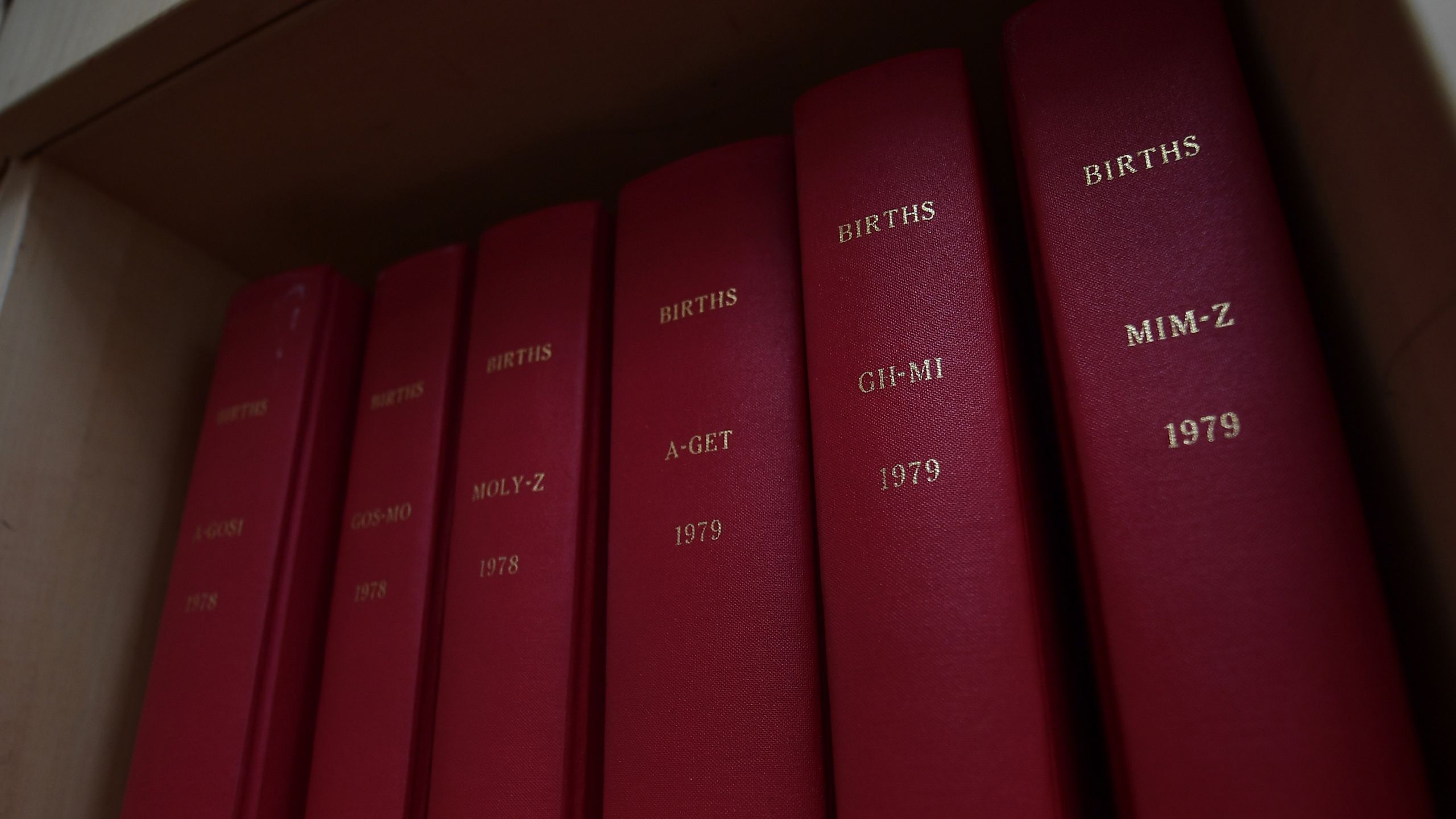

It is very difficult to request official identity documents if you do not know your birth name

It is very difficult to request official identity documents if you do not know your birth name

Adoptees’ original identity was kept secret for several reasons, including in cases where birth parents formally stated to authorities that they did not wish to be contacted by their child.

Previously, a birth parent's right to privacy could be given priority over their child’s right to know about their own birth, background and medical history.

However, the rules are changing under a new law which comes into full effect on 3 October.

The Birth Information and Tracing Act 2022 will give adult adoptees the right to access their birth certificate - a document which should tell them who their birth parents are.

The law also sets out how adoptees can apply for their childcare and family medical records, and makes it a criminal offence to destroy records relevant to adoption cases.

The Irish government hailed it as “landmark” legislation and undoubtedly, many people will finally get answers to lifelong questions.

But critics like the Clann Project argue adoptees will still face discrimination when accessing their own identity documents.

They also point out the law will not provide any additional rights to birth parents searching for their adult children.

Who do you think you are?

As an adopted man, John Tuthill never felt the urge to search for his biological family until he became a father in his late 20s.

“The most remarkable thing for me was when my eldest son was born,” he says.

Moments after giving birth, John's wife handed their baby to him and said: "Meet your first blood relative."

“It was kind of an eye-opening moment,” he recalls. “It wasn’t long after that then I was toying with the idea of finding my biological mother.”

But despite a 13-year search, John still has no confirmation of his birth identity.

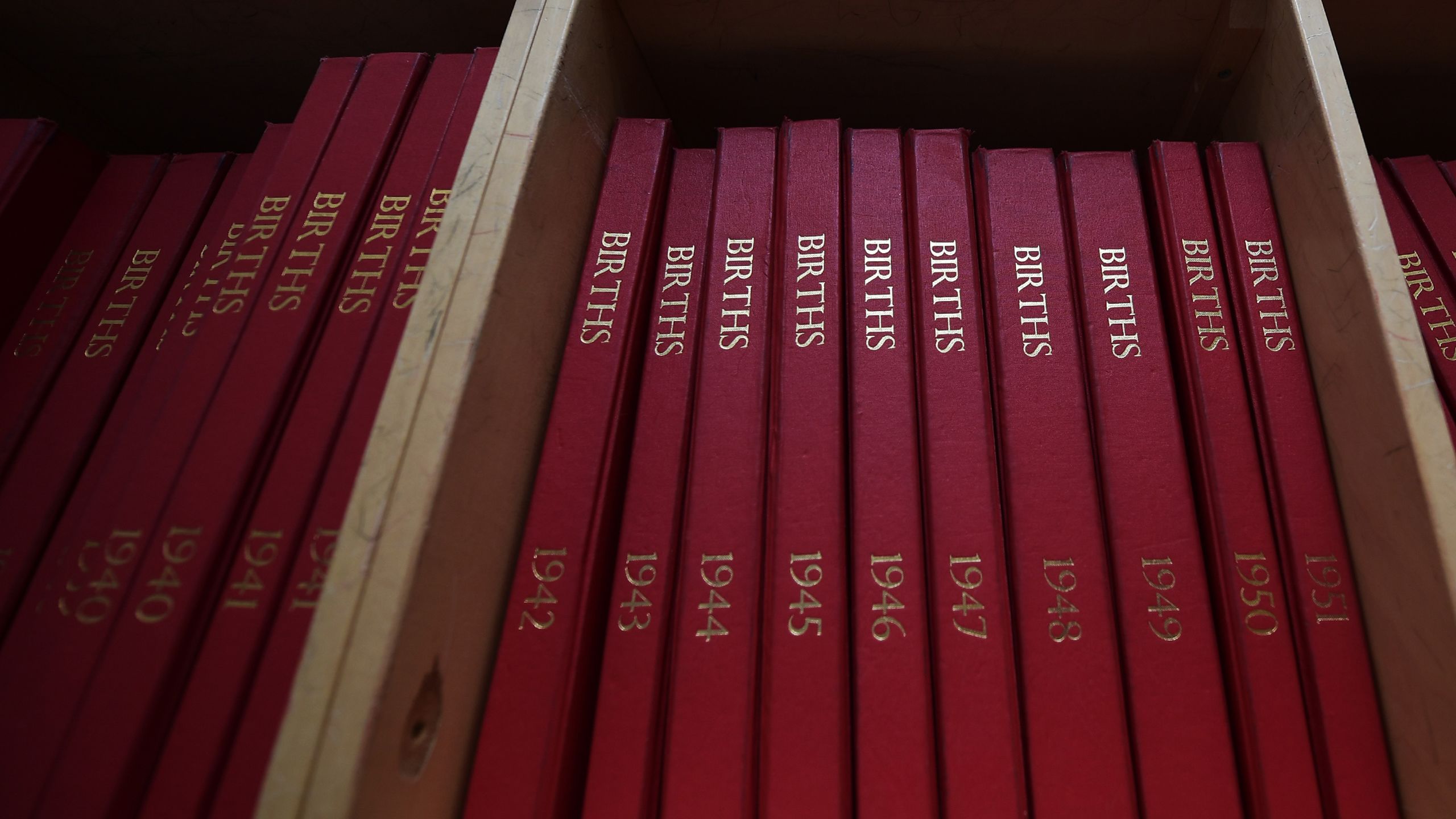

A photo of John as a young boy

A photo of John as a young boy

Adopted as a baby in 1979 from St Patrick’s Guild adoption home in Blackrock, County Dublin, he has no memory of the woman who gave birth to him.

John was raised by a married couple in County Kildare, who brought him up as one of their three adopted children.

John with his adoptive parents and his adopted brother and sister

John with his adoptive parents and his adopted brother and sister

“It was pretty obvious to me that I was adopted, given that I was the only black kid in the family,” he laughs.

But he says his adoptive parents did everything they could to give him a “fantastic” childhood and he “couldn’t have asked for a better mum and dad”.

Up until now, adoptees in Ireland were not automatically entitled to see their birth records, but authorities could often release snippets of non-identifying information about their birth families.

A few months into his search, a social worker informed John that his birth mother had six children in total, but that he was the only one who had a different father.

John’s biological parents met in London in the late 1970s.

His mother was pregnant when she came home to Ireland. She gave birth to John in a Dublin hospital and shortly afterwards he was placed for adoption.

“Unfortunately, it seems to be that she hadn’t told any of the rest of her family about me,” he says.

It appears that John’s biological father was never told about the pregnancy either.

According to his adoption records, John’s father was of Trinidad and Tobago descent and moved to Liverpool as a young boy.

“It was funny,” John laughs. “I had always been a Liverpool supporter from the time I was a small fella.”

John’s parents were in their late 20s when he was born, so when his search started, he felt there was every chance they were still alive.

His overriding hope was to meet his birth mother, but in January 2010 a letter arrived at his home to inform him that she had died more than a decade earlier.

No meeting, no phone call, just a letter telling him his mother was dead.

“I had always thought I had prepared myself for the possibility that she might not be alive,” he says.

“When I got the letter in the post to say that she’d passed away… even though I didn’t know the woman, it was a real kick in the guts and it was a real tough time.”

Despite that devastating blow, John still held on to hope that he could meet his half-siblings.

In order to trace any surviving brothers or sisters, John needed to know his own birth name and his mother’s identity.

But for the last 13 years - due to privacy rules governing adoption tracing services - John has been denied access to this information.

It meant that not only has he been unable to contact his living blood relatives, he could not even find out where his late mother was buried.

But rules are changing.

From now on, all legally adopted adults will be able to access their birth certificates, regardless of the circumstances of their birth.

John says as soon as his birth name is confirmed he will try again to contact his half-siblings and search for any surviving aunts and uncles.

But he is also aware of the possibility of rejection and will respect their wishes if they decide not to meet him.

“I have a whole other family out there to discover. They either accept me or they don’t, I don’t care, but at least I’ll know,” he says.

“For me, it’s just about completing me and, be it in a negative way or a positive way, at least it’ll be done.”

John is just one of thousands of people hoping the new Birth Information and Tracing Act will answer lifelong questions.

For adoptee Linda Southern, the first thing she wants to know is the name she was given on the day she was born.

“I’m 47 years old, born in Dublin, Ireland - which I’ve only just found out,” she says.

Linda pictured as a baby with her adoptive father and mother

Linda pictured as a baby with her adoptive father and mother

“I grew up the only child of two older parents who adopted me when I was six weeks old.”

Linda always wondered about her origins but it was not until 2021 that she requested her birth information from the child and family agency, Tusla.

When she received her documents, much of the information was obscured.

“Anything that had my name or my birth parents’ name on it was redacted, with basically a big black line,” Linda says.

An extract from the adoption documents that Linda received from Tusla

An extract from the adoption documents that Linda received from Tusla

She was told her information was withheld due to privacy and data protection concerns.

But the documents did confirm she was born to a 22-year-old woman in Dublin’s National Maternity Hospital.

The only information about her birth father is a note on the file which said: “Gone away.”

She assumes it is likely her mother came under pressure to place her for adoption due to societal attitudes.

“I was born in 1975. It was still in the era of Holy Catholic Ireland where church doctrine ruled the country,” Linda says.

“I would just like to tell her: ‘Don’t feel bad for what happened, I’ve lived a great life, I had a great family’.”

Linda as a child with her adoptive parents and grandmother

Linda as a child with her adoptive parents and grandmother

Although Linda is now entitled to see her unredacted birth certificate and would welcome contact with birth relatives, she intends to take things slowly.

“I would like to see a photograph of my birth mother and I would like to get to meet her, but I’m also very cautious about not doing any damage to her family.”

Raised in Dublin as an only child, Linda is also curious to know if she has any brothers or sisters.

“But would they welcome me would be the question,” she says. “How would they feel learning that their mother had a child outside marriage?”

Linda said it would feel strange if she discovers she is from a bigger family than the one she grew up in

Linda said it would feel strange if she discovers she is from a bigger family than the one she grew up in

Another aspect of having no information about her roots is that Linda could never answer doctors’ questions about her family’s medical history.

She has epilepsy and wants to know if the condition was inherited or if it developed as a result of a childhood car accident.

Then there was the issue of applying for jobs, some of which required identity documents Linda could never produce.

“They were saying to me: ‘Do you have a long-form birth cert?’

“Eh, no I don’t. Not under the name Linda Southern, because Linda Southern only existed from when I was six weeks old.

“That’s why I’d love to know my birth name.”

Still missing my baby

For many mothers still living with the pain of separation, placing their child for adoption was not a decision they felt they had any control over.

“It has left me and a lot of people traumatised, and no amount of counselling will get that pain away,” says Sharon McGuigan.

Sharon as a teenager, not long before she was sent to a mother and baby home

Sharon as a teenager, not long before she was sent to a mother and baby home

She had just turned 16 when she found out she was pregnant in 1985.

The schoolgirl was living with her parents in County Monaghan and was so frightened about the consequences, she kept her pregnancy secret for five months.

When it was discovered, she was sent alone on a bus to Dunboyne mother and baby home in County Meath, a Catholic-run facility for unmarried mothers.

This now-refurbished Georgian mansion housed Dunboyne mother and baby home from 1955 to 1991

This now-refurbished Georgian mansion housed Dunboyne mother and baby home from 1955 to 1991

She gave birth to a girl in Dublin’s National Maternity Hospital in February 1986.

Her daughter was born a month premature and taken straight to intensive care.

A week later, Sharon had to leave the hospital alone and was sent back to the mother and baby home where she “cried solid” for days.

Her parents came to collect her, but Sharon says her baby could not be mentioned in the family home.

And instead of going back to school, she was given a job washing dishes in a local hotel.

“I just felt so lost, I just felt as if my whole insides had been taken away,” she recalls.

Less than a year later, a social worker arrived and drove her to Carrickmacross to sign adoption papers.

“I don’t remember anything being explained or being asked: ‘Do you know what you’re doing?’” Sharon says.

“I was just told to ‘sign there’.

Aged just 17, and on her own, she remembers believing she had no choice but to do as she was told.

“I didn't question anything, I was so naive and so fearful,” she says.

“I probably was developing depression after the loss of my daughter - because it is a loss.”

Sharon’s story is far from unique, according to adoption rights campaigner, Claire McGettrick.

“I’ve heard countless testimony where women were told to: ‘Go away. What have you to offer this child?’ And in the face of that, they reluctantly signed adoption papers.”

Ms McGettrick adds that Ireland was not a country where single mothers could easily rear a child outside marriage, irrespective of her age or financial status.

She says she has heard accounts of many women who were much older than Sharon, well-established in professional careers, who felt pressurised into giving their babies up for adoption.

“It gives you a sense of just how oppressive and abusive the system was – that no matter who you were, you could not keep your child,” the campaigner says.

Last year, the Commission of Investigation into Irish Mother and Baby Homes bitterly disappointed former residents when it said it had found no evidence of “forced adoption”.

The commission said it accepted “that the mothers did not have much choice but that is not the same as ‘forced’ adoption”.

The 2021 mother and baby home report followed a six-year inquiry into the institutions in the Republic

The 2021 mother and baby home report followed a six-year inquiry into the institutions in the Republic

It was a finding that Ms McGettrick dismisses as “a nonsense” and one she says was made despite “widespread evidence to the contrary”.

She points to the personal testimonies of several former mother and baby home residents who told the inquiry they had signed adoption papers under duress.

“If you are leaving a woman or girl with no other choice, regardless of her circumstances, it’s forced adoption,” Ms McGettrick insists.

Sharon says she suffered from depression for at least 20 years after the adoption, and continually asked social workers about her daughter.

She was given photos of the child aged three months and 12 years, but after that, all communication stopped.

Sharon is now married with two more children, but still yearns to meet the child she was separated from 36 years ago.

Sharon with her husband and her two youngest children

Sharon with her husband and her two youngest children

“There’s not a day that I don’t think about my baby girl,” she says.

“It does leave an empty space in your heart."

A few years ago, with no prospect of help from the authorities, Sharon decided she would try to trace her adult daughter herself.

After trawling through records at the General Register Office, and getting assistance from a voluntary researcher, she got a name and address that she was “95% confident” was her own child.

Sharon then wrote her a letter telling her who she believed she was and explaining the circumstances of her adoption.

“I posted the letter and kind of thought: ‘Right, OK, that’s it. It’s up to her now’.”

Months later, an envelope decorated with butterfly stickers arrived at Sharon’s home.

“The letter sat on the table for ages before I opened it,” she recalls.

“It was like, I can't physically open this letter.”

When she finally plucked up the courage to read it, she saw her eldest daughter’s words in handwriting similar to her own.

“She told me she felt so sorry that I had to go through that at such a young age,” Sharon says.

“She wanted to know why she was in intensive care [after her birth]. I couldn't give that information because I didn't actually know myself.”

Sharon’s daughter also confirmed in writing that although she would be happy to keep in contact by letter, she did not wish to meet in person.

“It’s not exactly what I wanted, but it was more than I could hope for,” Sharon says.

Sharon revisited the site of the former Dunboyne Mother and Baby Home after it was redeveloped into a hotel

Sharon revisited the site of the former Dunboyne Mother and Baby Home after it was redeveloped into a hotel

She wrote back to her daughter saying she understood her wishes and would be content to stay in contact by writing.

But this time there was no reply. Several years have since passed with no further communication.

Sharon accepts she must respect her daughter’s wishes, but feels robbed of her relationship with her eldest child.

“Even though I have my life here - I have my two children here and I love them dearly, my husband and everything else - but there's always that one piece missing.”

A few years ago, she began communicating online with other birth mothers and found it cathartic as they were the only people she felt truly understood her pain.

Sharon now helps run the Facebook group Birth Mothers Ireland, which supports more than 60 Irish women separated from their children through adoption.

She says many of the members still have no contact with their children and “are hitting brick walls all the time” in their search for information.

Sharon is “delighted” that the new Birth Information and Tracing Act will give adoptees more rights and hopes it may result in reunions for her members.

But she is very disappointed that the right to information will not apply equally to birth parents searching for their adult children.

“I think they should be entitled to the same rights as adoptees, because they need to put closure to a trauma that they endured.

“And I think it should be equal, it should be open for both.”

Cross-border confusion

Loraine Jackson’s Irish birth certificate states she was born in Dublin on St Patrick’s Day, 1948.

But that isn’t true, she was actually born in Northern Ireland and was one of hundreds of babies moved across the Irish border for adoption.

Her real birth certificate shows she was born in Belfast’s Jubilee Maternity Hospital to a single mother called Annie Smith.

Belfast's Jubilee Maternity Hospital opened in 1935 (above) and was demolished in 2001

Belfast's Jubilee Maternity Hospital opened in 1935 (above) and was demolished in 2001

At the time, Annie was living in Woodvale Avenue in the north of the city, but she was originally from County Meath in the Republic of Ireland.

“I don’t know how she ended up in Belfast,” Loraine says of the mother she never got to know.

When she was just a few weeks old, Loraine was taken to the Bethany Home in Dublin, a Protestant-run institution which housed unmarried mothers and children.

She still does not know who took her over the border or how she made that journey.

At that time, adoption had been regulated in her native Northern Ireland for almost 20 years and the consent of a parent or guardian was required.

But it would be another four years before adoption was regulated in the Republic of Ireland.

Loraine as a baby, shortly after she went to live with her new family

Loraine as a baby, shortly after she went to live with her new family

Loraine spent the next few months in Bethany until adopted by a Protestant couple in Dublin.

In 1990, she began searching for her birth family, by which stage she was a mother in her early 40s.

“I started it off by writing to the Adoption Board in Ireland, which was the procedure at the time,” she explains.

During initial meetings with social workers, details of Loraine’s early life began to emerge, including the unexpected fact that she had been born in the UK.

But progress was slow and frustrated by privacy rules.

“They give you little titbits to tempt you," Loraine recalls. "But in general they’re tied to the laws and that’s it.”

Being born in a different jurisdiction complicated her search, but Loraine’s UK birth rights gave her an information advantage over adoptees born in the Republic.

A copy of Loraine's adoption certificate, issued in 1997

A copy of Loraine's adoption certificate, issued in 1997

The Adoption (Northern Ireland) Order 1987 had given adult adoptees the right to apply to the Registrar General for copy of their birth certificate.

However, as she was dealing mainly with social workers in the Republic, she did not know about this rule and spent the next quarter of a century with more questions than answers.

It was 2016 before Loraine received her first official copy of her Northern Ireland birth certificate.

The document made no mention of her birth father.

Loraine's Northern Ireland birth certificate shows her mother was resident in Belfast at the time

Loraine's Northern Ireland birth certificate shows her mother was resident in Belfast at the time

Loraine also obtained her baptismal record which shows she was christened Elsie Lillian Patricia Smith in St James’ Church of Ireland in Belfast in April 1948.

But getting hold of birth documents is no substitute for hugging a family member.

So she turned to an increasing popular method of family tracing which can often sidestep the authorities and international borders altogether – DNA tests.

The tests produced limited success at first, but during the 2020 coronavirus lockdown she tried a new company and got a surprise result.

“It’s almost immediate… I got this email to say so-and-so is your half-sister,” Loraine recalls.

“And not only had I a sister, I ended up having three sisters and three brothers who are children of my birth father, but a different birth mother.”

DNA tests also identified a distant relative on her mother’s side, a link which helped Loraine to find out a little more about the woman who gave birth to her.

Lorraine's birth mother Annie Cook (nee Smith) moved to Great Britain and lived into her 90s

Lorraine's birth mother Annie Cook (nee Smith) moved to Great Britain and lived into her 90s

“We found out that my mum had run away to the north of England and she ended up getting married and had another child, who is deceased unfortunately.

“But that would mean I would have seven siblings that I never knew about until two years ago.”

Ireland’s strict Covid-19 lockdowns meant Loraine could not meet her surviving relatives immediately, but as soon as restrictions lifted, she went to see her four half-siblings who still live in Ireland.

“Ah, it was great, it was lovely,” she says. “They're absolutely smashing people.”

Inevitably, the conversation turned to family resemblances.

“It’s so strange looking at people that look like you,” Loraine says.

“Because other than my own children, I never could see myself in anybody else, because I didn't know anybody who should look like me.

“But I mean, we’re the image of each other.”

Lorraine with her three half-sisters and three half-brothers in August 2022

Lorraine with her three half-sisters and three half-brothers in August 2022

This summer, Loraine’s siblings brought her with them to England to meet her two remaining brothers for the first time, including the baby of the bunch who is now in his 60s.

She says she has been “accepted whole-heartedly” by her new-found family.

“It’s just wonderful because I seemed to be in this fog before and the fog has lifted.”

But there are still many questions Loraine wants answered now that the full Birth Information and Tracing Act has taken effect.

Some relate to the care she received in the Bethany Home.

“My adoptive dad always said that I was in a dreadful state when they had me first,” she explains.

He told her she had severe nappy rash and did not look like a healthy baby.

Loraine has also suffered lifelong dental problems and wonders how much of that may stem from a lack of care in Bethany.

The former Bethany Home in Rathgar, County Dublin

The former Bethany Home in Rathgar, County Dublin

The ill-treatment of women and children in Irish mother and baby homes was by no means the sole preserve of the Catholic Church.

Bethany was among several institutions examined by Ireland’s Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes, a major inquiry which concluded last year.

In its final report, the commission said: “A very high rate of infant mortality was a common feature of all mother and baby homes until the late 1940s and Bethany was no exception.”

It said 262 children who spent time in the Bethany Home died in childhood, with the highest number of deaths recorded in the 1930s and 1940s.

Overcrowding, under-qualified staff, inadequate health facilities and Bethany’s “frequently dire financial pressures” were listed as contributory factors in the high death rate.

The full circumstances of Loraine’s cross-border journey are still to be revealed but it was not unique for a Bethany resident.

Of the 1,584 women who entered the home during its half century in operation, 139 gave addresses in Northern Ireland.

The home closed in 1971.

Evidently, mothers and children were sent in both directions.

A 2021 report into mother and baby homes in Northern Ireland concluded that “there was considerable cross-border movement of babies”.

It calculated that at least 493 babies born in Catholic mother and baby homes were moved across the border to the Republic of Ireland between 1942 and 1990.

The same cross-border journey was made by 58 children from the Salvation Army’s Thorndale House in Belfast between 1930 and 1970.

But the researchers said that without access to individual adoption files on both sides of the border “it cannot be confirmed that these adoptions were carried out following due legal process”.

Campaigner Claire McGettrick said she had come across “countless instances” of cross-border adoption because many religious orders continued to operate on an all-Ireland basis long after partition.

“Cross-border traffic was extremely common in my experience and I think the answer, as always, is access to records on an all-island basis so that we can truly understand this system.”

Truth at last?

For the first time in Irish history, adopted people now have the right to “full and unredacted access” to their birth records under the new Birth Information and Tracing Act.

A booklet about the new law was recently sent to every home in the Republic of Ireland

A booklet about the new law was recently sent to every home in the Republic of Ireland

The legislation was introduced by Minister for Children Roderic O’Gorman, who last month said it “conclusively addresses the wrongful denial of people's identity rights over many decades in this State”.

A new and improved adoption contact preference register opened on 1 July.

This allows adoptees and birth relatives to state what kind of communication, if any, they would like with a family member from whom they are separated through adoption.

From 3 October, birth certificates can be released to adoptees on request, whether or not their birth families object.

Requests for information can be made via a special website

Requests for information can be made via a special website

The Adoption Authority of Ireland (AAI) is the main organisation responsible for implementing the new rules and running the contact register.

Its chief executive, Patricia Carey, hailed it as a “landmark” law which will do “exactly what it says on the tin”.

“We’re giving the adult adoptees all of the information we hold about them. There isn’t going to be a restriction on the information they receive,” she said.

“Anyone who was legally adopted in Ireland, their original birth certificate can be issued to them within a very short period of time.”

However, the procedure will still differ in cases where birth families formally state they do not want to be contacted by an adoptee.

In “no contact” cases, birth records will only be released to an adoptee after they have participated in an “information session” with adoption authorities.

That session could be a meeting or a phone call, but during the conversation the adoptee must be advised of their birth relatives’ wishes.

There could be many reasons why people choose the no contact option.

Historical stigma about pregnancy outside marriage means some birth parents never told anyone they had a baby.

Some pregnancies were the result of rape or incest, and those mothers will have been deeply traumatised.

But adoption rights campaigners object to the mandatory sessions, saying it effectively means the state thinks it needs to “explain the concept of privacy” to adoptees.

“I don’t know in what world it’s OK to further punish affected people by expecting them to attend a demeaning and entirely unnecessary information session on privacy, simply to get what is already a public document,” says Clann’s Claire McGettrick.

Claire McGettrick objects to any law that treats people differently "simply because they are adopted"

Claire McGettrick objects to any law that treats people differently "simply because they are adopted"

But the Adoption Authority insists that the information sessions could be useful for some adoptees because even if a birth parent has registered a no contact preference, staff may be able to trace other blood relatives who do want a relationship.

No contact requests are relatively rare and currently make up slightly more than 2% of applications to Ireland’s contact preference registers.

Since the new statutory register opened on 1 July, more than 2,000 people have submitted their details and only 145 of them said they did not want to hear from a family member.

The AAI also holds details of 14,460 people who previously registered with the old National Adoption Contact Preference Register which opened in 2005.

Their names are being automatically added to the new system, including 248 applicants who registered a no contact preference.

Ms Carey says that even in such difficult cases, people often change their minds when there is careful mediation to “tease out the issues” causing concern.

“I think we know that the world and society has changed so much in the last 10 or 20 years that having these conversations is not as difficult as it may have been even back to the 70s or 80s.

“So a lot of people, once you sit down and talk to them, and encourage them to talk about relinquishing a child for adoption, they may actually change their preference.”

The AAI chief is aware that many people, frustrated with the authorities, often trace relatives themselves using methods such as DNA testing.

But she argues professional involvement may produce better outcomes in sensitive cases, because they can facilitate “gradual information sharing” between family members.

The Adoption Authority of Ireland is the central authority for adoption in the Republic

The Adoption Authority of Ireland is the central authority for adoption in the Republic

“The staff in the Adoption Authority are very skilled. They know how to discreetly make contact with somebody, build on a conversation where it’s not just: ‘Do you want to meet this person?’

“It might be: ‘Would you share a photograph? Would you share a letter?’”

In some cases unfortunately, it will be too late because adoptees will sadly discover their birth parents died before they got the chance to meet them.

But family can be much more than just a parent-child relationship.

Therefore, the AAI is encouraging anyone affected by adoption to sign up to the register as it will assist tracing services.

“For example somebody may not know that they have siblings or half-siblings, but we will know because both parties have registered and we’ll be able to effectively match the details,” Ms Carey says.

In recent years, family tracing services have been overwhelmed with requests.

The Clann Project regularly deals with people “waiting years” for tracing assistance and is sceptical that agencies will be able to cope with the expected surge in demand.

Ms McGettrick says organisations which hold adoption records have “secrecy built into their DNA” and she is concerned the legislation leaves them too much room to interpret which documents they should release.

“We’re very, very worried that quite a lot of records will slip through the net.”

However, the Department of Children told BBC News NI the new law will give adoptees “full access to all of his or her information - no redactions; nothing held back”.

The Birth Information and Tracing Act 2022 was published earlier this year

The Birth Information and Tracing Act 2022 was published earlier this year

It added that previous delays were “exacerbated by an absence of clear legislation,” whereas the new rules will allow information requests to be processed faster.

As well as the new tracing service, the department has promised that counselling and support will be provided on request.

When asked about tracing resources, it said Tusla is getting a 5% increase to its overall budget – an extra €41m (£36.2) – part of which will allow it to hire additional staff to meet demand.

The AAI has been allocated an extra €1.34m (£1.2m) to help it implement the new law.

The department said it was confident birth information requests would be processed within the legal deadlines, but added it was difficult to estimate how long tracing cases would take.

In cases of illegal adoption, where births have been deliberately concealed or falsely registered, tracing could be extremely difficult and time-consuming.

Adoption rights campaigners argue the legislation does not address all outstanding issues and much more is needed than a simple release of birth records.

“It’s not just good enough to find out what your original name was,” Ms McGettrick says.

"You have to find out the story of how that came to be."

Related links:

Birth Information & Tracing Act 2022

Contact Preference Register

Credits:

Photography:

Charles McQuillan

Additional Images:

Niall Carson / Press Association

Oireachtas.ie / Irish Parliament

Adoption Authority of Ireland

Niall Meehan

Belfast Health and Social Care Trust

Video Journalist:

Niall McCracken

Assistant Editor:

Judith Cummings

Editor:

Pauline McKenna