Were these the three hours that upset Trump’s campaign?

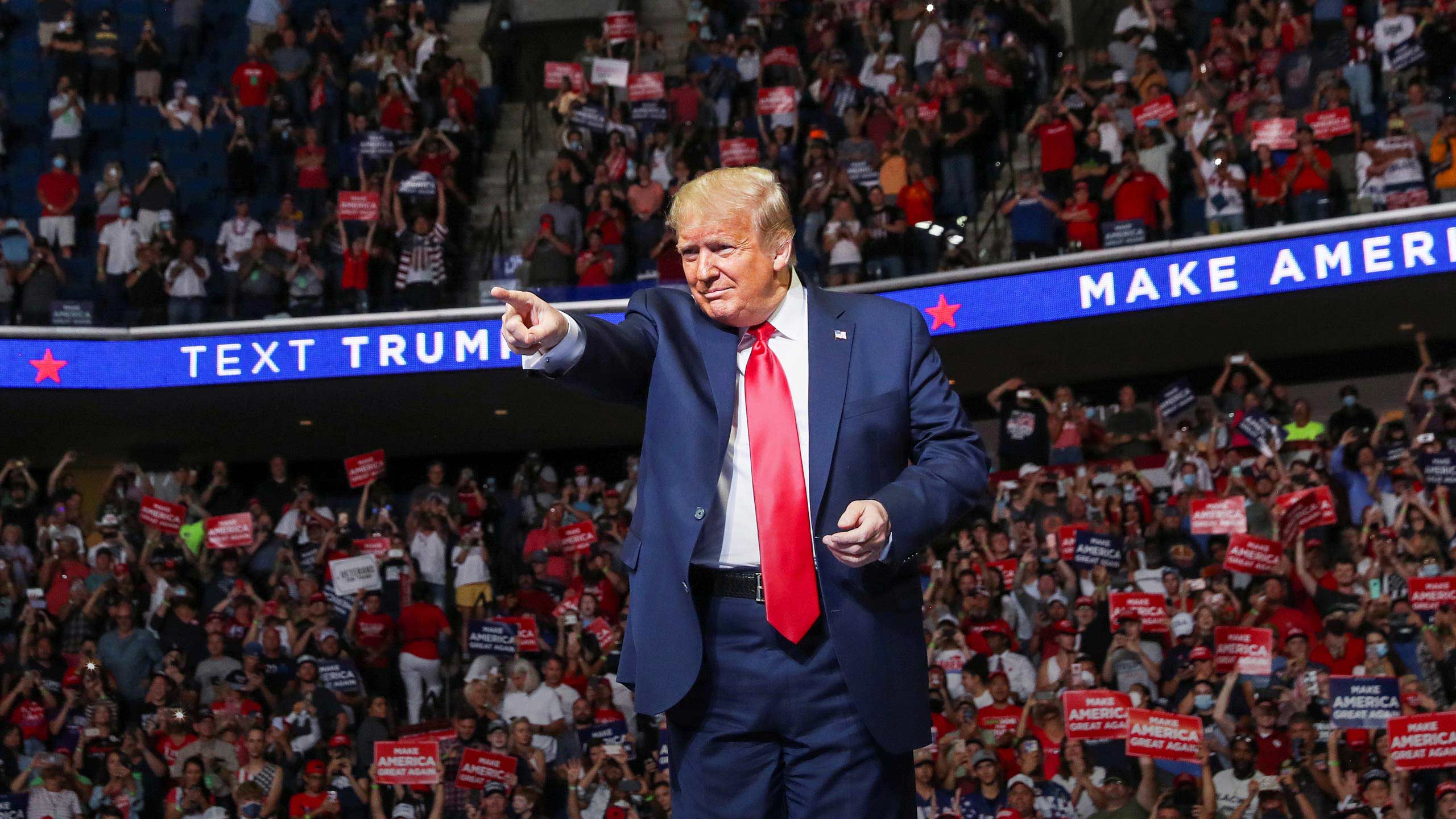

It was an epic and tumultuous day by any standards, and rarely in politics have the extremes of emotion been so perfectly captured by the cameras. That day was 20 June.

This was to be the grand relaunch of the Trump re-election campaign. Coronavirus was now in the rear-view mirror. This would be the first rally since lockdown. The first opportunity to bask in the adoration of his supporters. This would be a turning point moment.

It would be a vivid symbol of America going back to normal life, of rebirth - and Donald Trump, who’d felt like a caged animal cooped up in the White House, would be unleashed to do what he does best - firing up his audience.

Tulsa would be a refocusing of 2020, putting it back on the path the president and his strategists had mapped in the lead up to November’s election. As Air Force One came to a halt at Tulsa International Airport on a bright Oklahoma summer’s day and the hatch opened, there - waiting impatiently to get out - was President Trump.

He was jovial. Playful. Skittish almost. He was pouting for the cameras and was pulling teasing faces: “Shall I come down the stairs or not?” “Should I, shouldn’t I?”

And then, much later, there was his arrival back at the White House later that night, where Marine One had ferried him back to the South Lawn from Andrews Airforce Base in Maryland. He got off the chopper and the man looked broken. His spirit crushed. In my years covering Donald Trump, I had never seen him like this. His red tie was undone. His jacket weighed heavily on his shoulders. He forced the thinnest but weariest of smiles for the cameras, and trudged back to the Residence. Disconsolate. Dishevelled. And seemingly defeated.

Arrival in Tulsa and return to Maryland

There have probably been worse days - having to fire his first national security adviser, discovering that his then attorney general had recused himself from the Russia investigation, finding out that a whistleblower had complained about his call to the president of Ukraine, that set in train the impeachment proceedings. And then there was the badge of dishonour of becoming only the third US president to be impeached. The disclosure that he’d paid off a porn star $130,000 (£100,000) before the election was embarrassing and difficult personally.

But the better days of the Trump presidency were to be the building blocks of his re-election campaign, and what his advisers had started to believe would set him on a glide path to victory. And in a word, this all came down to one thing - the economy. The best days were when the president would sign a new executive order that would strip away this or that piece of Obama-era regulatory red tape that inhibited business from developing and growing.

Trump would look at the dizzying rise of the Dow and the Nasdaq, and tweet approvingly. Perhaps the best day of all came with the legislative victory to reform and simplify America’s arcane tax code. It was a big win. As 2019 became 2020, everything seemed to be set fair on the economic front. Nothing on the dashboard was flashing red, and the engine was purring - unemployment was at a record low, growth was ticking upwards, inflation was not a problem, consumer confidence was on the rise. When the Senate voted not to convict him early in 2020, after he’d been impeached by the lower house, the last remaining obstacle to an improbable second term seemed to have been removed.

That all changed when the coronavirus outbreak took hold and the heartbreaking decision had to be taken by Donald Trump to shutter the economy. Every day of the shutdown, the president was looking at ways to reopen, and to reinstate the election strategy built around the economic success story he wanted to impress upon the American people.

That is what made Tulsa such a consequential day. Because this would be the day when the president would pivot away from the virus and go back to the strong economy election playbook. He was excited about it. His wealthy business friends had been urging him to embrace this moment.

But this day would show the limits of Donald Trump’s power in the face of an enemy, the likes of which he had never encountered before. It was a day which changed the direction of his presidency.

It was an epic and tumultuous day by any standards, and rarely in politics have the extremes of emotion been so perfectly captured by the cameras. That day was 20 June.

This was to be the grand relaunch of the Trump re-election campaign. Coronavirus was now in the rear-view mirror. This would be the first rally since lockdown. The first opportunity to bask in the adoration of his supporters. This would be a turning point moment.

It would be a vivid symbol of America going back to normal life, of rebirth - and Donald Trump, who’d felt like a caged animal cooped up in the White House, would be unleashed to do what he does best - firing up his audience.

Tulsa would be a refocusing of 2020, putting it back on the path the president and his strategists had mapped in the lead up to November’s election. As Air Force One came to a halt at Tulsa International Airport on a bright Oklahoma summer’s day and the hatch opened, there - waiting impatiently to get out - was President Trump.

He was jovial. Playful. Skittish almost. He was pouting for the cameras and was pulling teasing faces: “Shall I come down the stairs or not?” “Should I, shouldn’t I?”

And then, much later, there was his arrival back at the White House later that night, where Marine One had ferried him back to the South Lawn from Andrews Airforce Base in Maryland. He got off the chopper and the man looked broken. His spirit crushed. In my years covering Donald Trump, I had never seen him like this. His red tie was undone. His jacket weighed heavily on his shoulders. He forced the thinnest but weariest of smiles for the cameras, and trudged back to the Residence. Disconsolate. Dishevelled. And seemingly defeated.

Arrival in Tulsa

Return to Maryland

There have probably been worse days - having to fire his first national security adviser, discovering that his then attorney general had recused himself from the Russia investigation, finding out that a whistleblower had complained about his call to the president of Ukraine, that set in train the impeachment proceedings. And then there was the badge of dishonour of becoming only the third US president to be impeached. The disclosure that he’d paid off a porn star $130,000 (£100,000) before the election was embarrassing and difficult personally.

But the better days of the Trump presidency were to be the building blocks of his re-election campaign, and what his advisers had started to believe would set him on a glide path to victory. And in a word, this all came down to one thing - the economy. The best days were when the president would sign a new executive order that would strip away this or that piece of Obama-era regulatory red tape that inhibited business from developing and growing.

Trump would look at the dizzying rise of the Dow and the Nasdaq, and tweet approvingly. Perhaps the best day of all came with the legislative victory to reform and simplify America’s arcane tax code. It was a big win. As 2019 became 2020, everything seemed to be set fair on the economic front. Nothing on the dashboard was flashing red, and the engine was purring - unemployment was at a record low, growth was ticking upwards, inflation was not a problem, consumer confidence was on the rise. When the Senate voted not to convict him early in 2020, after he’d been impeached by the lower house, the last remaining obstacle to an improbable second term seemed to have been removed.

That all changed when the coronavirus outbreak took hold and the heartbreaking decision had to be taken by Donald Trump to shutter the economy. Every day of the shutdown, the president was looking at ways to reopen, and to reinstate the election strategy built around the economic success story he wanted to impress upon the American people.

That is what made Tulsa such a consequential day. Because this would be the day when the president would pivot away from the virus and go back to the strong economy election playbook. He was excited about it. His wealthy business friends had been urging him to embrace this moment.

But this day would show the limits of Donald Trump’s power in the face of an enemy, the likes of which he had never encountered before. It was a day which changed the direction of his presidency.

Why Tulsa?

The Trump campaign wanted somewhere to make a splash. A campaign rally. Pumping music. Big-name speakers who would act as the warm-up, culminating in the president taking the stage. It didn’t need to be in a swing state. It needed to be somewhere where the crowds would be sizeable and enthusiastic. And scarcely anywhere in the Union is more enthusiastic than Oklahoma - Trump won here by 36% four years ago. It needed to be in a state where Covid-19 numbers weren’t too bad.

On 10 June, during a White House event, the president casually mentioned that for the first time since shutdown in March, he would hold a rally the following Friday. It seemed to catch the campaign off guard, and scrambling to catch up with something the president had announced - not for the first time. But confirmation came. It was to be at the BOK Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma, capacity 19,500, on Friday 19 June.

One of the many things that makes the Trump presidency unique is his love of the rally. Nearly all of his predecessors saw the election-style rally as a necessary part of running for an election, but once you are installed in the White House you have to get on with the governing. But Trump - the classic outsider - is much more comfortable when he’s on the road, talking to the people who propelled him to an election victory.

When his internal battery is showing only one bar, plugging into 20,000 cheering fans is what gives him a full recharge. It is also what allows him to stay tuned into the preoccupations of ordinary Americans - not just the preoccupations of what he sees as the liberal elite who dominate Washington and much of the media. He spits out ideas and sees what response he gets - and a lot of the issues the president campaigns on are road-tested at his rallies first.

But this 19 June rally? It caused dangerous levels of blowback.

There was an immediate outcry. The week the rally was announced was when the protests against the death of George Floyd were at their height, and there was a febrile atmosphere in much of the US. It was just days after Trump took that walk from the White House, across Lafayette Park, to pose for the cameras with a Bible outside St John’s Episcopal Church. The so-called church of presidents, which stands on the junction of H and 16th Streets in DC, had been vandalised in the demonstrations. To facilitate this photo opportunity, thousands of peaceful protesters were cleared by police using batons, stun grenades and tear gas.

President Trump outside St John’s Church, Washington DC

The day he was proposing to hold his rally - 19 June - is known in the US as “Juneteenth”. It commemorates the day in 1865 when federal troops marched into Galveston, Texas, to take control of the state and order that anyone still enslaved be freed immediately. This was two years after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. Juneteenth marks the end of slavery.

The White House initially batted away calls to change the date. The president then stated he had put Juneteenth on the map by planning to hold the event on this day. “I did something good: I made Juneteenth very famous,” Trump told the Wall Street Journal. “It’s actually an important event, an important time. But nobody had ever heard of it.” Well, every year the Trump White House has put out a press release to mark the day. But that’s a quibble. I think it was a day that was pretty well established in the minds of the nation’s African-American population long before the Trump campaign settled on that date to hold a rally.

There was one other problem, given the sensitivities, that seemingly hadn’t been given any consideration by the wise owls in the Trump campaign - not only the when, but the where.

Tulsa was the scene of America’s worst ever race massacre.

Why Tulsa?

The Trump campaign wanted somewhere to make a splash. A campaign rally. Pumping music. Big-name speakers who would act as the warm-up, culminating in the president taking the stage. It didn’t need to be in a swing state. It needed to be somewhere where the crowds would be sizeable and enthusiastic. And scarcely anywhere in the Union is more enthusiastic than Oklahoma - Trump won here by 36% four years ago. It needed to be in a state where Covid-19 numbers weren’t too bad.

On 10 June, during a White House event, the president casually mentioned that for the first time since shutdown in March, he would hold a rally the following Friday. It seemed to catch the campaign off guard, and scrambling to catch up with something the president had announced - not for the first time. But confirmation came. It was to be at the BOK Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma, capacity 19,500, on Friday 19 June.

One of the many things that makes the Trump presidency unique is his love of the rally. Nearly all of his predecessors saw the election-style rally as a necessary part of running for an election, but once you are installed in the White House you have to get on with the governing. But Trump - the classic outsider - is much more comfortable when he’s on the road, talking to the people who propelled him to an election victory.

When his internal battery is showing only one bar, plugging into 20,000 cheering fans is what gives him a full recharge. It is also what allows him to stay tuned into the preoccupations of ordinary Americans - not just the preoccupations of what he sees as the liberal elite who dominate Washington and much of the media. He spits out ideas and sees what response he gets - and a lot of the issues the president campaigns on are road-tested at his rallies first.

But this 19 June rally? It caused dangerous levels of blowback.

There was an immediate outcry. The week the rally was announced was when the protests against the death of George Floyd were at their height, and there was a febrile atmosphere in much of the US. It was just days after Trump took that walk from the White House, across Lafayette Park, to pose for the cameras with a Bible outside St John’s Episcopal Church. The so-called church of presidents, which stands on the junction of H and 16th Streets in DC, had been vandalised in the demonstrations. To facilitate this photo opportunity, thousands of peaceful protesters were cleared by police using batons, stun grenades and tear gas.

President Trump outside St John’s Church, Washington DC

The day he was proposing to hold his rally - 19 June - is known in the US as “Juneteenth”. It commemorates the day in 1865 when federal troops marched into Galveston, Texas, to take control of the state and order that anyone still enslaved be freed immediately. This was two years after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. Juneteenth marks the end of slavery.

The White House initially batted away calls to change the date. The president then stated he had put Juneteenth on the map by planning to hold the event on this day. “I did something good: I made Juneteenth very famous,” Trump told the Wall Street Journal. “It’s actually an important event, an important time. But nobody had ever heard of it.” Well, every year the Trump White House has put out a press release to mark the day. But that’s a quibble. I think it was a day that was pretty well established in the minds of the nation’s African-American population long before the Trump campaign settled on that date to hold a rally.

There was one other problem, given the sensitivities, that seemingly hadn’t been given any consideration by the wise owls in the Trump campaign - not only the when, but the where.

Tulsa was the scene of America’s worst ever race massacre.

In 1921, at the end of May beginning of June, white supremacists ran amok. Hundreds were killed, thousands lost their homes. The city’s Greenwood area had been dubbed the “Black Wall Street”. It was up and coming, prosperous even. But it was stirring resentment.

A large number of the white residents were given arms and made deputies by city officials - and that night, at the end of May 99 years ago, they torched the black area of the city.

Black Wall Street memorial, Tulsa

Referring to the rally, Kamala Harris - then just a California senator, and well before she was put on the ticket by Joe Biden - accused the president in a tweet of throwing white supremacists a “welcome home party”.

The impression was given - mistakenly - that Trump is impervious to criticism and pressure. He isn’t, but it takes a lot for him to change his mind. The optics on Tulsa were becoming hideous. His people wanted this to be all about the campaign relaunch, not about the time and place. So, the president caved, tweeting this:

“Many of my African American friends and supporters have reached out to suggest that we consider changing the date out... of respect for this Holiday, and in observance of this important occasion and all that it represents. I have therefore decided to move our rally to Saturday, June 20th, in order to honor their requests.”

In 1921, at the end of May beginning of June, white supremacists ran amok. Hundreds were killed, thousands lost their homes. The city’s Greenwood area had been dubbed the “Black Wall Street”. It was up and coming, prosperous even. But it was stirring resentment.

A large number of the white residents were given arms and made deputies by city officials - and that night, at the end of May 99 years ago, they torched the black area of the city.

Black Wall Street memorial, Tulsa

Referring to the rally, Kamala Harris - then just a California senator, and well before she was put on the ticket by Joe Biden - accused the president in a tweet of throwing white supremacists a “welcome home party”.

The impression was given - mistakenly - that Trump is impervious to criticism and pressure. He isn’t, but it takes a lot for him to change his mind. The optics on Tulsa were becoming hideous. His people wanted this to be all about the campaign relaunch, not about the time and place. So, the president caved, tweeting this:

“Many of my African American friends and supporters have reached out to suggest that we consider changing the date out... of respect for this Holiday, and in observance of this important occasion and all that it represents. I have therefore decided to move our rally to Saturday, June 20th, in order to honor their requests.”

That was one problem solved. But the pesky pandemic was still an issue that needed to be cauterised. This was a multi-dimensional problem. First of all, if you’re going to have 19,500 in a packed arena whooping and hollering, what happens if someone catches the virus?

Enter the lawyers. Anyone signing up for the rally online was met with a disclaimer, informing them of the risk of exposure to Covid-19 “in any public place where people are present”.

It went on to warn that by attending the rally, Trump supporters and their guests “voluntarily assume all risks related to exposure to Covid-19” and agree not to hold the campaign, Tulsa’s BOK Center or a whole pile of other related parties “liable for any illness or injury”.

BOK Center in Tulsa

No mention was made of any social-distancing requirements or other safety precautions that would be in place at the rally, nor did it note the recommendation by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that Americans wear face coverings while indoors, in situations where social distancing might be difficult. The campaign told everyone that hand-san and masks would be available on arrival.

The next hurdle was the Tulsa health department. Officials said the rally was irresponsible and dangerous, and took the Trump campaign to court to have it called off. But the Oklahoma Supreme Court ruled in favour of the campaign.

The Trump team were beside themselves with excitement. So many people had registered to attend that they announced there would be a spillover rally outside the BOK Center, at which both the president and Vice President Mike Pence would speak.

The figures were incredible. A million people had signed up to attend. On Twitter, I pointed out the sheer improbability of that - it is over twice the population of the whole city. But the Trump campaign insisted it was true. They were back up and running, and not only was Trump keen as mustard to get out on the road, America - if Tulsa was anything to go by - was just as anxious to see him.

That was one problem solved. But the pesky pandemic was still an issue that needed to be cauterised. This was a multi-dimensional problem. First of all, if you’re going to have 19,500 in a packed arena whooping and hollering, what happens if someone catches the virus?

Enter the lawyers. Anyone signing up for the rally online was met with a disclaimer, informing them of the risk of exposure to Covid-19 “in any public place where people are present”.

It went on to warn that by attending the rally, Trump supporters and their guests “voluntarily assume all risks related to exposure to Covid-19” and agree not to hold the campaign, Tulsa’s BOK Center or a whole pile of other related parties “liable for any illness or injury”.

BOK Center in Tulsa

No mention was made of any social-distancing requirements or other safety precautions that would be in place at the rally, nor did it note the recommendation by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that Americans wear face coverings while indoors in situations, where social distancing might be difficult. The campaign told everyone that hand-san and masks would be available on arrival.

The next hurdle was the Tulsa health department. Officials said the rally was irresponsible and dangerous, and took the Trump campaign to court to have it called off. But the Oklahoma Supreme Court ruled in favour of the campaign.

The Trump team were beside themselves with excitement. So many people had registered to attend that they announced there would be a spillover rally outside the BOK Center, at which both the president and Vice President Mike Pence would speak.

The figures were incredible. A million people had signed up to attend. On Twitter, I pointed out the sheer improbability of that - it is over twice the population of the whole city. But the Trump campaign insisted it was true. They were back up and running, and not only was Trump keen as mustard to get out on the road, America - if Tulsa was anything to go by - was just as anxious to see him.

Saturday 20 June

Just before 16:00 the president left the White House and stopped to speak to reporters in the rain. He was seething about the book written by his former National Security Advisor, John Bolton.

He wanted him prosecuted for revealing state secrets. He wanted the money he was making from the book confiscated. Then there was the firing of a district attorney in New York. On this, the president was defensive - that’s a matter for the attorney general, not me, he told reporters.

But on Tulsa, he was clearly pumped. “The event in Oklahoma is unbelievable,” he told the journalists. “The crowds are unbelievable. They haven’t seen anything like it. We will go there now. We’ll give a hopefully good speech, see a lot of great people, a lot of great friends.”

President Trump boards Air Force One

At 17:51 local time, Air Force One landed in Tulsa. As the door opened and the steps were brought alongside the aircraft, Trump playfully pointed to the crowd. You could just sense the release he was feeling at being unshackled from his coronavirus house arrest.

But as “The Beast” - the president’s armoured Cadillac and the convoy of support vehicles made their way into the city, the news coming from the BOK Center was bad.

The million predicted had turned into a paltry few thousand.

The special waiver given to Nigel Farage, the leader of Britain’s Brexit Party, to fly from London to the US the day before the rally seemed to have been a waste of time. He was down to address the overflow rally for the hundreds of thousands who wouldn’t be able to get into the arena. But there was no-one in the overflow, and Trump campaign staff were panicking. Not only was the outdoor rally empty, the main event inside the BOK Center was nowhere near its 19,500 capacity.

Police and Black Lives Matter protesters in Tulsa

Appeals were put out on social media to encourage people to come to see the president speak. They stayed away. The Trump campaign said people gave up because there were Black Lives Matter protesters intimidating the Trump supporters, making it impossible for people to get to the venue. But there was a massive police presence, and in total there were less than a handful of arrests.

Confirmation by the Trump campaign that morning, that six staffers who’d been involved in setting up the rally - the advance team - had tested positive for Covid-19, incensed the president. It was one of many things that led to a darkening of his mood during the course of the day.

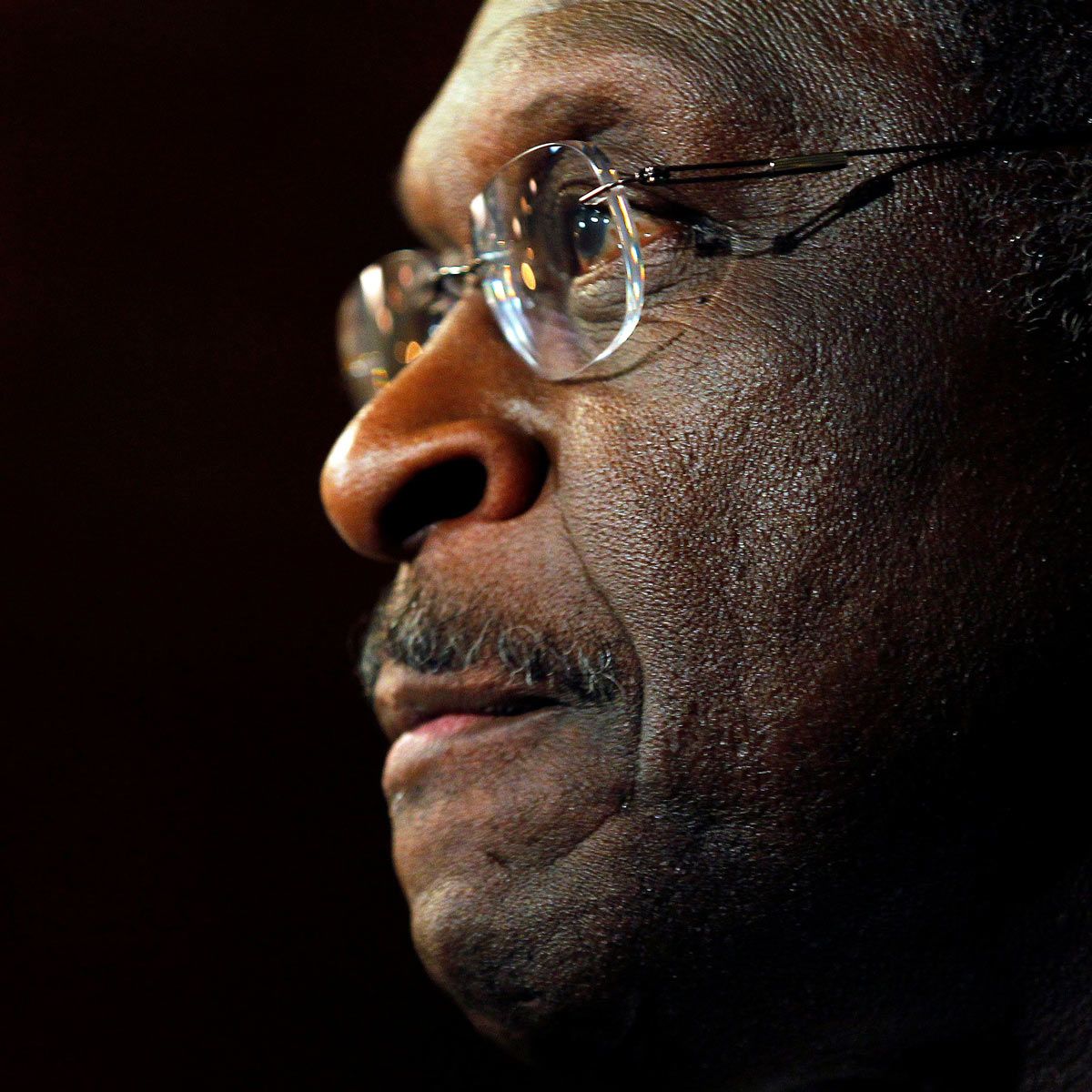

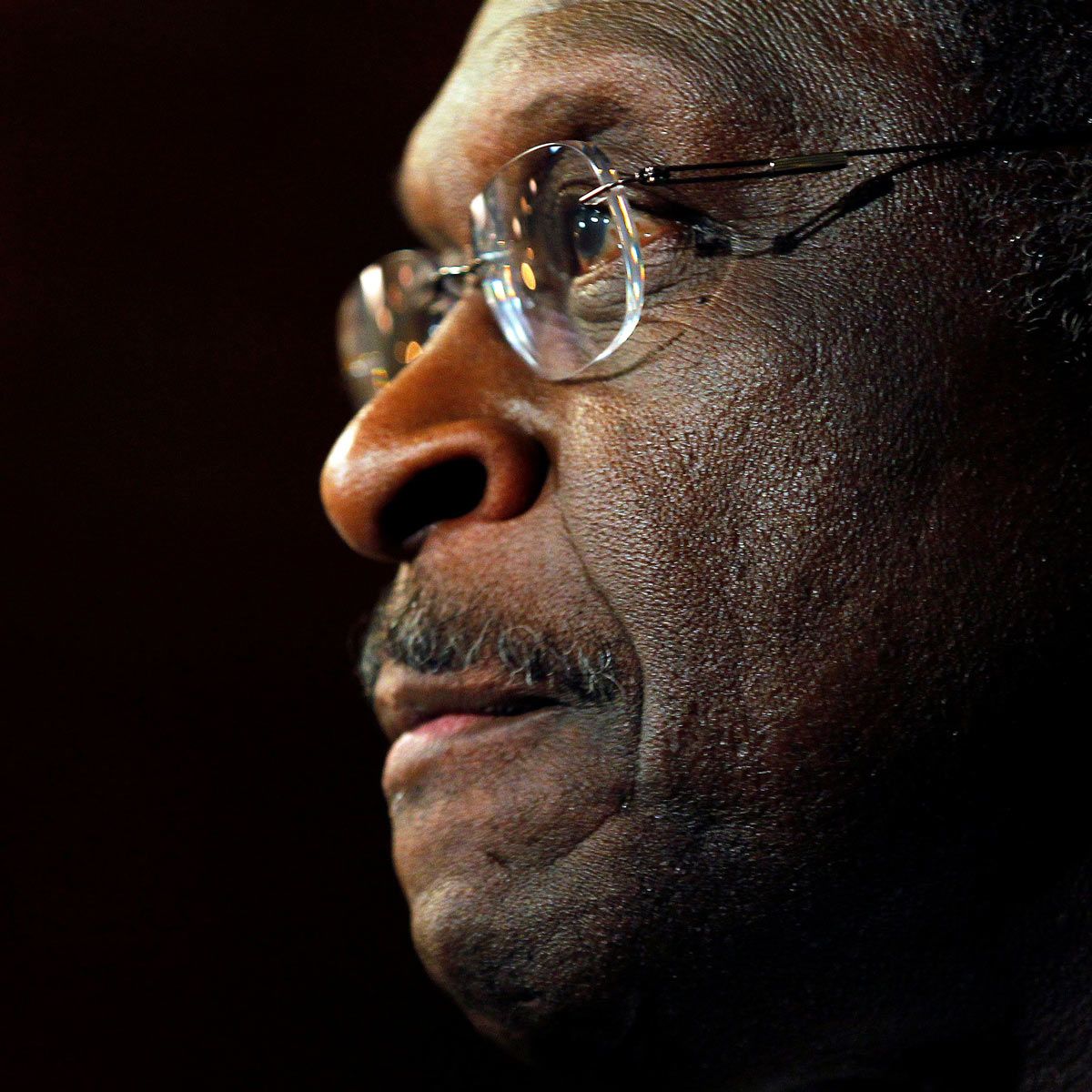

There was an array of Trump family members, congressional representatives and local politicians. One of the richest African-Americans - and someone who went for the Republican nomination as president - Herman Cain, was there. He tweeted a photo of himself and friends waiting for the rally to begin. They, like virtually everyone else inside the arena, were not wearing masks and were not doing any social distancing - at least in this team photo. Ditto Oklahoma’s Governor Kevin Stitt.

Kevin Stitt (centre left) and Herman Cain (centre right) in the BOK Center

In preparation for the rally, venue staff had put stickers on every other seat asking people not to sit on them. It was part of the attempts to maintain social distancing within the venue. But with hours to go before the president was due on stage, the Trump campaign organisers asked for the notices to be removed. Spokesman Tim Murtaugh would later insist, “The rally was in full compliance with local requirements. In addition, every rally attendee received a temperature check prior to admission, was given a face mask, and provided ample access to hand sanitizer.”

There was no attempt to answer the charge that they ordered the removal of the notices which would have afforded some level of social distancing - something the doctors on the White House Coronavirus Taskforce had said was essential to stop the spread of the disease.

Saturday 20 June

Just before 16:00 the president left the White House and stopped to speak to reporters in the rain. He was seething about the book written by his former National Security Advisor, John Bolton.

He wanted him prosecuted for revealing state secrets. He wanted the money he was making from the book confiscated. Then there was the firing of a district attorney in New York. On this, the president was defensive - that’s a matter for the attorney general, not me, he told reporters.

But on Tulsa, he was clearly pumped. “The event in Oklahoma is unbelievable,” he told the journalists. “The crowds are unbelievable. They haven’t seen anything like it. We will go there now. We’ll give a hopefully good speech, see a lot of great people, a lot of great friends.”

President Trump boards Air Force One

At 17:51 local time, Air Force One landed in Tulsa. As the door opened and the steps were brought alongside the aircraft, Trump playfully pointed to the crowd. You could just sense the release he was feeling at being unshackled from his coronavirus house arrest.

But as “The Beast” - the president’s armoured Cadillac and the convoy of support vehicles made their way into the city, the news coming from the BOK Center was bad.

The million predicted had turned into a paltry few thousand.

The special waiver given to Nigel Farage, the leader of Britain’s Brexit Party, to fly from London to the US the day before the rally seemed to have been a waste of time. He was down to address the overflow rally for the hundreds of thousands who wouldn’t be able to get into the arena. But there was no-one in the overflow, and Trump campaign staff were panicking. Not only was the outdoor rally empty, the main event inside the BOK Center was nowhere near its 19,500 capacity.

Black Lives Matter protesters in Tulsa

Appeals were put out on social media to encourage people to come to see the president speak. They stayed away. The Trump campaign said people gave up because there were Black Lives Matter protesters intimidating the Trump supporters, making it impossible for people to get to the venue. But there was a massive police presence, and in total there were less than a handful of arrests.

Confirmation by the Trump campaign that morning, that six staffers who’d been involved in setting up the rally - the advance team - had tested positive for Covid-19, incensed the president. It was one of many things that led to a darkening of his mood during the course of the day.

There was an array of Trump family members, congressional representatives and local politicians. One of the richest African-Americans - and someone who went for the Republican nomination as president - Herman Cain, was there. He tweeted a photo of himself and friends waiting for the rally to begin. They, like virtually everyone else inside the arena, were not wearing masks and were not doing any social distancing - at least in this team photo. Ditto Oklahoma’s Governor Kevin Stitt.

In the BOK Center - Kevin Stitt (centre left) and Herman Cain (centre right)

In preparation for the rally, venue staff had put stickers on every other seat asking people not to sit on them. It was part of the attempts to maintain social distancing within the venue. But with hours to go before the president was due on stage, the Trump campaign organisers asked for the notices to be removed. Spokesman Tim Murtaugh would later insist, “The rally was in full compliance with local requirements. In addition, every rally attendee received a temperature check prior to admission, was given a face mask, and provided ample access to hand sanitizer.”

There was no attempt to answer the charge that they ordered the removal of the notices which would have afforded some level of social distancing - something the doctors on the White House Coronavirus Taskforce had said was essential to stop the spread of the disease.

It is hard to exaggerate just how much this rally was at odds with all the advice being dispensed by the White House - which was to avoid large crowds and big gatherings indoors where the virus spreads much more easily, and also to maintain social distancing and wear a mask.

Outside, staff were positioned under tents near the various entry points to the arena, to hand out masks to anyone who wanted one. But no-one was obliged to go past these collection points, and few did. The peer pressure was going in one direction - “If the president isn’t going to wear one, why should I?”

Vice President Mike Pence in Tulsa

Outwardly, everyone backstage was in “the show must go on” mode. Vice President Pence went on to make his speech. But after he finished, he headed straight back to Washington, without waiting for Trump to deliver his remarks.

That was highly unusual, to put it mildly.

Trump was beaming when he went on stage. The fire marshal later confirmed there were 6,200 people inside the arena when the main act came out. Or to put it another way - it was two-thirds empty. Or to put it another way still, that was a smaller number than Sha Na Na attracted, The Pips (without Gladys), Loverboy and The West Virginia Touring Company performing La Traviata.

It is hard to exaggerate just how much this rally was at odds with all the advice being dispensed by the White House - which was to avoid large crowds and big gatherings indoors where the virus spreads much more easily, and also to maintain social distancing and wear a mask.

Outside, staff were positioned under tents near the various entry points to the arena, to hand out masks to anyone who wanted one. But no-one was obliged to go past these collection points, and few did. The peer pressure was going in one direction - “If the president isn’t going to wear one, why should I?”

Vice President Mike Pence in Tulsa

Outwardly, everyone backstage was in “the show must go on” mode. Vice President Pence went on to make his speech. But after he finished, he headed straight back to Washington, without waiting for Trump to deliver his remarks.

That was highly unusual, to put it mildly.

Trump was beaming when he went on stage. The fire marshal later confirmed there were 6,200 people inside the arena when the main act came out. Or to put it another way - it was two-thirds empty. Or to put it another way still, that was a smaller number than Sha Na Na attracted, The Pips (without Gladys), Loverboy and The West Virginia Touring Company performing La Traviata.

The speech - given that it was meant to be his big campaign relaunch - was thin on detail. There were no big overarching themes. Nor were there any new eye-catching policy announcements.

To put this in rock ‘n’ roll terms, he’d come to play the back catalogue and nothing from the new album. This was the greatest hits compilation - that always goes down well with the crowd. On coronavirus, he joked about the variety of names there were for the disease, at one stage using a term many Chinese Americans find deeply offensive. The comment that got most pick-up was his suggestion that states were doing too much testing, and that he wanted to slow it down - so that, in turn, would bring down the number of new cases America was reporting.

On George Floyd and the protests that had convulsed every big city across the whole of the US, he said nothing. It was as if the events that had gripped the US have no part in this venue, and were no concern for his base.

The most time he devoted to any one topic in the speech, was his apparent difficulty walking down a ramp the previous week. He had gone to West Point military academy to give a speech to cadets, and when he took a drink of water, he rather oddly held on to the glass with both hands. When he walked down the ramp at the end of his speech, he appeared worried that he was going to lose his footing. It quickly became a source of much mirth on social media. The president went through a blow-by-blow deconstruction of what happened, which lasted the best part of 17 minutes. In a nutshell, the media had stitched him up.

At the end of the Tulsa speech - as is the tradition - the Rolling Stones’ 1969 classic You Can’t Always Get What You Want fired up, as the president waved to the audience before walking off backstage.

The papers would report that Donald Trump had a Vesuvial eruption once he’d come off stage, lashing out at his campaign organisers for screwing up. But I have spoken to a senior Trump adviser who was with him throughout the day. He says Trump may well have exploded, but, he insists, he never saw that. Instead, he painted a far more revealing and nuanced picture. He said the president was unusually quiet. He was sullen and disappointed, and bitter his people hadn’t levelled with him about the likely turnout. So much emotional energy had been invested in Tulsa, and there had been no return. It was the relaunch that never got off the launch pad. At 21:01, he left the arena.

This account of the presidential mood aligns much more closely with what the world saw when the president dragged himself off Marine One at the White House late that night.

The speech - given that it was meant to be his big campaign relaunch - was thin on detail. There were no big overarching themes. Nor were there any new eye-catching policy announcements.

To put this in rock ‘n’ roll terms, he’d come to play the back catalogue and nothing from the new album. This was the greatest hits compilation - that always goes down well with the crowd. On coronavirus, he joked about the variety of names there were for the disease, at one stage using a term many Chinese Americans find deeply offensive. The comment that got most pick-up was his suggestion that states were doing too much testing, and that he wanted to slow it down - so that, in turn, would bring down the number of new cases America was reporting.

On George Floyd and the protests that had convulsed every big city across the whole of the US, he said nothing. It was as if the events that had gripped the US have no part in this venue, and were no concern for his base.

The most time he devoted to any one topic in the speech, was his apparent difficulty walking down a ramp the previous week. He had gone to West Point military academy to give a speech to cadets, and when he took a drink of water, he rather oddly held on to the glass with both hands. When he walked down the ramp at the end of his speech, he appeared worried that he was going to lose his footing. It quickly became a source of much mirth on social media. The president went through a blow-by-blow deconstruction of what happened, which lasted the best part of 17 minutes. In a nutshell, the media had stitched him up.

At the end of the Tulsa speech - as is the tradition - the Rolling Stones’ 1969 classic You Can’t Always Get What You Want fired up, as the president waved to the audience before walking off backstage.

The papers would report that Donald Trump had a Vesuvial eruption once he’d come off stage, lashing out at his campaign organisers for screwing up. But I have spoken to a senior Trump adviser who was with him throughout the day. He says Trump may well have exploded, but, he insists, he never saw that. Instead, he painted a far more revealing and nuanced picture. He said the president was unusually quiet. He was sullen and disappointed, and bitter his people hadn’t levelled with him about the likely turnout. So much emotional energy had been invested in Tulsa, and there had been no return. It was the relaunch that never got off the launch pad. At 21:01, he left the arena.

This account of the presidential mood aligns much more closely with what the world saw when the president dragged himself off Marine One at the White House late that night.

After Tulsa

On Twitter and Facebook the next day, there was a slightly forlorn effort by the president’s allies to portray Tulsa as a great success, but the words ring hollow. Trump loyalists went into damage limitation mode. There was an insistence there were no missteps - the event was a success. But all the time they knew someone was going to have to walk the plank. The president does not suffer humiliation like this without someone having to pay the price.

In mid-July it was announced that the campaign manager, Brad Parscale, had been demoted. The Facebook announcement came on the same day that a slew of polls showed Trump’s standing with the public was sliding - and the common factor in all these snapshots of public opinion was an accusation of his erratic handling of the pandemic.

Brad Parscale

There was one group though, that was well and truly celebrating on the day after Tulsa. The claim was that a million had signed up for his rally. But it turned out that many of those who had registered to attend never had any intention of going anywhere near Tulsa. They were a teenage generation of TikTok users who had decided to register for a laugh, to mess with the campaign organisers. It was a huge joke played on the social media masterminds of the Trump campaign, who consider themselves the smartest and most savvy in the business.

At the end of July, Trump announced he was going to shut down TikTok because of its Chinese ownership, and the possibility that the app owners were harvesting data (something the company fiercely denies) and passing it on to the Beijing government. This would be the latest manifestation of an ever-souring relationship with China.

President’s Twitter account and TikTok logo

In the days following the rally it was confirmed that two dozen secret service agents had been quarantined after showing symptoms of the virus.

This was followed by a news conference given by the Tulsa Health Department, where its executive director, Bruce Dart, said the Trump rally “more than likely” contributed to a big spike in coronavirus cases - which the city was now having to grapple with.

Separately, it was announced that Herman Cain had contracted Covid-19, testing positive nine days after the rally. He was admitted to hospital and, on 30 July, there was a sombre announcement - the 74-year-old co-chair of Black Voices for Trump had become the latest victim of coronavirus.

Herman Cain

No-one can say with 100% certainty that he contracted the virus at the rally.

The president paid tribute to him saying he had died of the “China virus”. What he doesn’t say is that the last time he was seen in public was at the BOK Center in Tulsa on 20 June.

The maskless Oklahoma governor Kevin Stitt also has contracted the virus.

The initial instinct was to press on regardless - act as though nothing untoward had happened. Three days after Tulsa, the president travelled to Phoenix, Arizona, where he spoke at a Students for Trump event to discuss “cancel culture” - the term for when individuals or companies face swift public backlash and boycott over offensive statements or actions. “We’re here today to declare that we will never cave to the left wing and the left-wing intolerance,” the president told his audience, packed tight into the Dream City Megachurch.

Students for Trump event in Arizona

Almost no-one was wearing protective masks and there were no temperature checks for the estimated 3,000-strong audience. The plea to take public-health seriously from the Democratic mayor the day before had fallen on deaf ears. Arizona would soon afterwards become one of the worst hit states - not because of this event, but it further underlined the incompatibility of holding mass, indoor audience events, with people packed tight, when you are fighting coronavirus.

And the campaign had a whole pile of rallies and venues to follow. Next up would be Portsmouth, New Hampshire, a blue-collar state the Democrats only just held on to in 2016, and where the Republicans are eyeing a possible gain in November. In one concession to the growing chorus of concern from public health officials and opponents, it was announced the 11 July rally would be held in a semi-outdoor space - an aircraft hangar, perhaps a test run for future events.

The state’s Republican governor, Chris Sununu, gave his blessing to the rally taking place - but added he would not be attending, invoking safety concerns related to the coronavirus. And Governor Sununu was not alone. An Ipsos poll published days before the rally found that around 76% of Americans said they were worried about catching the virus - up from 69% in June. And It is the reversal of a trend from April when anxiety about the virus was in decline.

But then enter Tropical Storm Fay. The day before the rally was due to be held it was abruptly called off. A Trump campaign official said it had been postponed for “safety reasons” because of the storm. But for the preceding 12 hours before this announcement, the weather forecast had predicted New Hampshire would not be hit.

Saturday 11 July was a breezy, sunny day in New Hampshire with clear blue skies. Trump taunters were joyfully tweeting. Which brings us to the other narrative - what led to the cancellation of New Hampshire was the fear that this could be another Tulsa, with the president playing to another less than full house.

On 11 July, the president visited a military medical centre in Maryland

Though the president insisted Tulsa was a success - that it brought record numbers of viewers to Fox News; that there were twice the number of people attending than the fire marshal had reported (the president offers no evidence for this claim) - Tulsa has not been repeated. The New Hampshire rally has not been reinstated. There has been no rally since Tulsa.

And most telling of all about the change that Oklahoma brought, was that the plans to have a packed, raucous Republican convention, with balloons and ticker tape and all the hoopla that goes with these quadrennial set pieces have been abandoned too. The convention had been due to be held in Charlotte, North Carolina. But when the governor of that state said there would have to be social distancing, the president announced that would not be acceptable, and he would find somewhere else to pack an auditorium. The president would instead give his acceptance speech in Jacksonville, Florida, after being formally nominated as the Republican candidate.

But even that had to be abandoned. Coronavirus was on the rise again, spiking massively in Florida. It has brought an important reality check for Donald Trump. Few politicians are better at shaping their own reality and imposing their own narrative on the national conversation. Even fewer politicians have shown the same alacrity for doubling down when they are in a tight spot as Trump. Coronavirus has shown the limits of presidential power.

After Tulsa

On Twitter and Facebook the next day, there was a slightly forlorn effort by the president’s allies to portray Tulsa as a great success, but the words ring hollow. Trump loyalists went into damage limitation mode. There was an insistence there were no missteps - the event was a success. But all the time they knew someone was going to have to walk the plank. The president does not suffer humiliation like this without someone having to pay the price.

In mid-July it was announced that the campaign manager, Brad Parscale, had been demoted. The Facebook announcement came on the same day that a slew of polls showed Trump’s standing with the public was sliding - and the common factor in all these snapshots of public opinion was an accusation of his erratic handling of the pandemic.

Brad Parscale

There was one group though, that was well and truly celebrating on the day after Tulsa. The claim was that a million had signed up for his rally. But it turned out that many of those who had registered to attend never had any intention of going anywhere near Tulsa. They were a teenage generation of TikTok users who had decided to register for a laugh, to mess with the campaign organisers. It was a huge joke played on the social media masterminds of the Trump campaign, who consider themselves the smartest and most savvy in the business.

At the end of July, Trump announced he was going to shut down TikTok because of its Chinese ownership, and the possibility that the app owners were harvesting data (something the company fiercely denies) and passing it on to the Beijing government. This would be the latest manifestation of an ever-souring relationship with China.

President’s Twitter account and TikTok logo

In the days following the rally it was confirmed that two dozen secret service agents had been quarantined after showing symptoms of the virus.

This was followed by a news conference given by the Tulsa Health Department, where its executive director, Bruce Dart, said the Trump rally “more than likely” contributed to a big spike in coronavirus cases - which the city was now having to grapple with.

Separately, it was announced that Herman Cain had contracted Covid-19, testing positive nine days after the rally. He was admitted to hospital and, on 30 July, there was a sombre announcement - the 74-year-old co-chair of Black Voices for Trump had become the latest victim of coronavirus.

Herman Cain

No one can say with 100% certainty that he contracted the virus at the rally.

The president paid tribute to him saying he had died of the “China virus”. What he doesn’t say is that the last time he was seen in public was at the BOK Center in Tulsa on 20 June.

The maskless Oklahoma governor Kevin Stitt also has contracted the virus.

The initial instinct was to press on regardless - act as though nothing untoward had happened. Three days after Tulsa, the president travelled to Phoenix, Arizona, where he spoke at a Students for Trump event to discuss “cancel culture” - the term for when individuals or companies face swift public backlash and boycott over offensive statements or actions. “We’re here today to declare that we will never cave to the left wing and the left-wing intolerance,” the president told his audience, packed tight into the Dream City Megachurch.

Students for Trump event in Arizona

Almost no-one was wearing protective masks and there were no temperature checks for the estimated 3,000-strong audience. The plea to take public-health seriously from the Democratic mayor the day before had fallen on deaf ears. Arizona would soon afterwards become one of the worst hit states - not because of this event, but it further underlined the incompatibility of holding mass, indoor audience events, with people packed tight, when you are fighting coronavirus.

And the campaign had a whole pile of rallies and venues to follow. Next up would be Portsmouth, New Hampshire, a blue-collar state the Democrats only just held on to in 2016, and where the Republicans are eyeing a possible gain in November. In one concession to the growing chorus of concern from public health officials and opponents, it was announced the 11 July rally would be held in a semi-outdoor space - an aircraft hangar, perhaps a test run for future events.

The state’s Republican governor, Chris Sununu, gave his blessing to the rally taking place - but added he would not be attending, invoking safety concerns related to the coronavirus. And Governor Sununu was not alone. An Ipsos poll published days before the rally found that around 76% of Americans said they were worried about catching the virus - up from 69% in June. And It is the reversal of a trend from April when anxiety about the virus was in decline.

But then enter Tropical Storm Fay. The day before the rally was due to be held it was abruptly called off. A Trump campaign official said it had been postponed for “safety reasons” because of the storm. But for the preceding 12 hours before this announcement, the weather forecast had predicted New Hampshire would not be hit.

Saturday 11 July was a breezy, sunny day in New Hampshire with clear blue skies. Trump taunters were joyfully tweeting. Which brings us to the other narrative - what led to the cancellation of New Hampshire was the fear that this could be another Tulsa, with the president playing to another less than full house.

On 11 July, the president visited a military medical centre in Maryland

Though the president insisted Tulsa was a success - that it brought record numbers of viewers to Fox News; that there were twice the number of people attending than the fire marshal had reported (the president offers no evidence for this claim) - Tulsa has not been repeated. The New Hampshire rally has not been reinstated. There has been no rally since Tulsa.

And most telling of all about the change that Oklahoma brought, was that the plans to have a packed, raucous Republican convention, with balloons and ticker tape and all the hoopla that goes with these quadrennial set pieces have been abandoned too. The convention had been due to be held in Charlotte, North Carolina. But when the governor of that state said there would have to be social distancing, the president announced that would not be acceptable, and he would find somewhere else to pack an auditorium. The president would instead give his acceptance speech in Jacksonville, Florida, after being formally nominated as the Republican candidate.

But even that had to be abandoned. Coronavirus was on the rise again, spiking massively in Florida. It has brought an important reality check for Donald Trump. Few politicians are better at shaping their own reality and imposing their own narrative on the national conversation. Even fewer politicians have shown the same alacrity for doubling down when they are in a tight spot as Trump. Coronavirus has shown the limits of presidential power.

Trump believed all he had to do was announce a rally, and the crowds would come flocking. They might still love him and might still vote for him in November, but they’re not going to pack arenas in the middle of a pandemic.

Tulsa may not have brought a loss of confidence - an important component for all successful politicians, but it has brought a wariness. And Trump’s most senior advisers know they can’t afford another Tulsa.

If the crowds stay away then it will be all too easy for the impression to take hold that Donald Trump is in decline

Support for Joe Biden in Oshkosh, Wisconsin

Tulsa had one other effect. Since then, Joe Biden’s position in the polls has been improving markedly, opening up significant leads in the key swing states that will determine the outcome of November’s election.

For much of the lockdown, Biden remained at his home in Wilmington, Delaware, conducting interviews and running campaign events via video link from his basement. The low-key approach means he has been a beneficiary of all the focus being on Donald Trump.

The failure of Tulsa, in other words, has totally upended the Trump campaign strategy. It has left a giant hole in campaign planning. How is the president going to project himself between now and November? And with what message? All we do know is that his convention is going to feature the exact same teleconferencing that the president had lambasted Joe Biden for during campaigning.

And as if all this wasn’t bad enough, to add insult to injury, the Rolling Stones management has since contacted the Trump campaign demanding that it stop playing the band’s music at Trump events. Tulsa showed the president that he can’t always get what he wants. Nor what he needs.

Trump believed all he had to do was announce a rally, and the crowds would come flocking. They might still love him and might still vote for him in November, but they’re not going to pack arenas in the middle of a pandemic.

Tulsa may not have brought a loss of confidence - an important component for all successful politicians, but it has brought a wariness. And Trump’s most senior advisers know they can’t afford another Tulsa. If the crowds stay away then it will be all too easy for the impression to take hold that Donald Trump is in decline

Support for Joe Biden in Wisconsin

Tulsa had one other effect. Since then, Joe Biden’s position in the polls has been improving markedly, opening up significant leads in the key swing states that will determine the outcome of November’s election.

For much of the lockdown, Biden remained at his home in Wilmington, Delaware, conducting interviews and running campaign events via video link from his basement. The low-key approach means he has been a beneficiary of all the focus being on Donald Trump.

The failure of Tulsa, in other words, has totally upended the Trump campaign strategy. It has left a giant hole in campaign planning. How is the president going to project himself between now and November? And with what message? All we do know is that his convention is going to feature the exact same teleconferencing that the president had lambasted Joe Biden for during campaigning.

And as if all this wasn’t bad enough, to add insult to injury, the Rolling Stones management has since contacted the Trump campaign demanding that it stop playing the band’s music at Trump events. Tulsa showed the president that he can’t always get what he wants. Nor what he needs.

Credits:

Author: Jon Sopel

Editor: Kathryn Westcott

Producer: Paul Kerley

Images: Getty Images, Reuters

Published August 2020

More long reads

Joe Biden: This time the Oval Office?

The inferno and the mystery ship

The Mangrove Nine: Echoes of black lives matter from 50 years ago