How did my sleepy hometown become a violent crime hotspot?

I returned to Huddersfield to write an article about a police shooting.

I found violence, rumours and a wall of silence.

I was born and raised in Huddersfield. It’s the town I lived in for the first 18 years of my life, and it’s a place that's still close to my heart. It’s where I got my first job as a journalist on a local newspaper before leaving to pursue my career. So, when the police shooting of a 28-year-old man, rumoured to be a gangster, made national headlines I decided it was time to return to my hometown and start asking some questions.

Yassar Yaqub was was shot and killed by police on 2 January 2017

Yassar Yaqub was was shot and killed by police on 2 January 2017

The investigation lasted almost two years, and its findings suggested links between Huddersfield and the national and international drugs trade. I found out that British Pakistanis are significantly overrepresented when it comes to convictions for intent to supply class A drugs in Yorkshire and Humber. Why was this happening in my community, and was there a link with the death of a local man named Yassar Yaqub?

Trying to answer these questions would lead me to confront the painful truth that my once sleepy, northern hometown now seemed to be a hotbed of violence, gangs and drug dealing.

The 'good son'

After he was shot, there was an outpouring of support for Yassar, who left behind two young kids. His friends spoke movingly of him as a “loving guy”. His parents, understandably, were distraught. His mum mourned passionately and publicly, while his dad demanded answers.

A Justice for Yassar banner on display near his family home in Huddersfield

A Justice for Yassar banner on display near his family home in Huddersfield

It was early 2018 when I first met Yassar’s dad, Mohammed Yaqub. By that time, Yassar’s death had become one of the biggest news stories ever linked to Huddersfield. The car he was travelling in was forced to stop by unmarked police cars. Soon after, an officer opened fire and Yassar was shot and killed. I wanted to know, how did a young man from my hometown end up being shot by the police on a motorway slip road?

Within weeks, I was invited into the Yaqub family home. The house dominates the street it’s on, with multiple security cameras visible to anyone walking past. I knew Yassar’s dad was a successful businessman and he happily admitted to giving his son everything he wanted. “I wish I had spoilt him even more,” he told me.

Mohammed Yaqub, Yassar's dad

Mohammed Yaqub, Yassar's dad

Yassar had been living with his parents when he died. I was shown around his bedroom, unchanged since his death, and heard how he liked designer clothes and “looking after himself”. Contrary to rumours of a gangster lifestyle, Mohammed said his son had worked for the family’s luxury car business and that he had just £68 in his bank account when he died.

Mohammed invited me to cover one of the Justice 4 Yassar campaign rallies in May 2018. The gathering, complete with banners and balloons to mark what would have been Yassar's 30th birthday, took place just off the M62, in the same place where Yassar was shot and killed by a police officer. The rally drew a crowd of between 50 and 100 people including Yassar’s family and many of his closest friends. Mohammed told me that he believed his son’s death was an “assassination” and that his “only reason for living now” was to get justice.

It was hard to get an idea of what Yassar was really like just from talking to people who knew him at the campaign rally. They tended to speak about him in quite a general way, telling me things like Yassar was “the nicest guy” who would “buy your shopping for you.” Any further questions would often result in silence or people asking me not to quote them.

Later that year, Mohsin Amin, 32, Rexhino Arapaj, 28, and David Butlin, 39, the men with whom Yassar had spent his final hours, would go on trial for a gun offence. These men were all friends of Yassar and had been travelling with him on the M62 in the last moments of his life. If Yassar had been alive, he would have been facing the same charge of conspiracy to possess a firearm with intent to endanger life.

I hoped the trial would give me an unfiltered insight into who Yassar Yaqub really was.

Back home

Soon after returning to my hometown, I began hanging out on Blacker Road - the street I lived on for the first 16 years of my life. Birkby is an area that has a large Pakistani population, and Blacker Road is the busiest part of the neighbourhood. Just drinking tea in one of the takeaways, near my old house, meant I’d bump into people I’d grown up with. The response was always warm and I got to chat to people I hadn’t seen for decades.

I had my notepad in hand, so it was only a matter of time before people would ask, “What are you doing back?” My response, and particularly the name “Yassar Yaqub”, were like kryptonite.

Over and over again, people I knew and trusted would explain that they “wouldn’t want to be seen” to say anything. Words like “rumour”, “stories” and “snitch” would come up. When I’d ask for an explanation, the conversation would stand still. I could see fear in their eyes. Some people even said I should be careful about what I was getting myself into. I knew the case had everyone talking. So why the silence?

Most people went quiet when I mentioned Yassar's name

Most people went quiet when I mentioned Yassar's name

I’d been aware of the rumour that Yassar Yaqub had been involved in drug dealing. Local news reports about his death, and the subsequent Justice 4 Yassar campaign, mentioned that opinion was divided about whether or not Yassar was involved in criminality. It’s an allegation his dad has strenuously and consistently denied, telling me that rumours about drug dealing were “completely false”.

While I was working out what to make of it all, a more immediate story started unfolding around me.

'Major incident reported'

It was a cold winter night. The sky was lit up by blue flashing lights. The sound of a helicopter rumbled in the distance. Two men had run into a local takeaway on Blacker Road trailing blood. They’d been stabbed. By the time I arrived on the scene, the men were in hospital but the blood stains they’d left on the floor of the shop were still visible.

The shopkeeper showed me pictures he'd taken of the scene

The shopkeeper showed me pictures he'd taken of the scene

Since my return to Huddersfield, I had heard talk of a rise in violence across town. So I decided to stick around and investigate. That was how I came to be standing on my old road staring at a wall of police vehicles - trying to see if anyone could shed light on what had just happened.

A young butcher told me the incident started in a local park - less than 50 metres from my childhood home - the two men had run into the takeaway for help. When I asked if the stabbing victims were “apne” (which loosely translates from Urdu as “one of our own”), the answer was yes.

It was clear from everyone’s reaction that this wasn’t a one-off. When I spoke to the owner of the takeaway he said that, in his opinion, violent incidents in the area were on the rise. He also said that local dealers sometimes came to buy food from him, but that he left them alone for fear they might pull a knife or a gun on him. I almost couldn’t believe what I was hearing. I remembered this town as a calm, happy place.

Days later, while I was still trying to get my head around the double stabbing on my old street, I heard there had been another incident nearby - a shooting in broad daylight. Since when did that happen that in my hometown?

Over the following weeks and months, I saw more police tape in Huddersfield than I’ve ever seen in London. Each incident would follow the same pattern: families stranded outside because their street was cordoned off; locals reluctantly telling me they’d heard gunshots, seen blood on the floor or witnessed a masked man speeding off into the distance. Once again, people were afraid to talk for fear of retribution. The words “young”, “Pakistani” and “man” kept coming up, as well as suggestions that the violence was the result of some kind of drug turf war.

“It’s getting out of control - you can’t pop down to the shop without a bulletproof vest anymore,” one woman said to me, as I stood there, staring in shock at what I was hearing.

If shooting and stabbings really were the new normal, this wasn’t the West Yorkshire I remembered. But was I just being nostalgic about my childhood?

I began gathering reports. An FOI submitted by a local newspaper showed that, from when Yassar Yaqub was killed in January 2017 to August 2018, more than 95 incidents involving firearms had occurred in the Kirklees district (of which Huddersfield is the largest town). In the two years prior to Yassar’s death, there were almost another 100 firearms-related incidents in the same area. This meant that, at that time, there had been almost 200 incidents involving guns reported in my area in less than four years.

The violence was clustered in areas like Birkby where I used to live or Fartown where I went to school. The more shocking events I witnessed, and the more I read about the spike in violence, the more I wanted to find out what was fuelling it - and how, if at all, Yassar Yaqub fitted into the story.

I was shocked to discover how much violence had occurred in the area I'd grown up in

I was shocked to discover how much violence had occurred in the area I'd grown up in

Many of the locations that had been reported as the scenes of shootings by the local news over the last few years were familiar to me, but one address in particular stood out. It was the street Yassar used to live on but there was no mention of his name in the report.

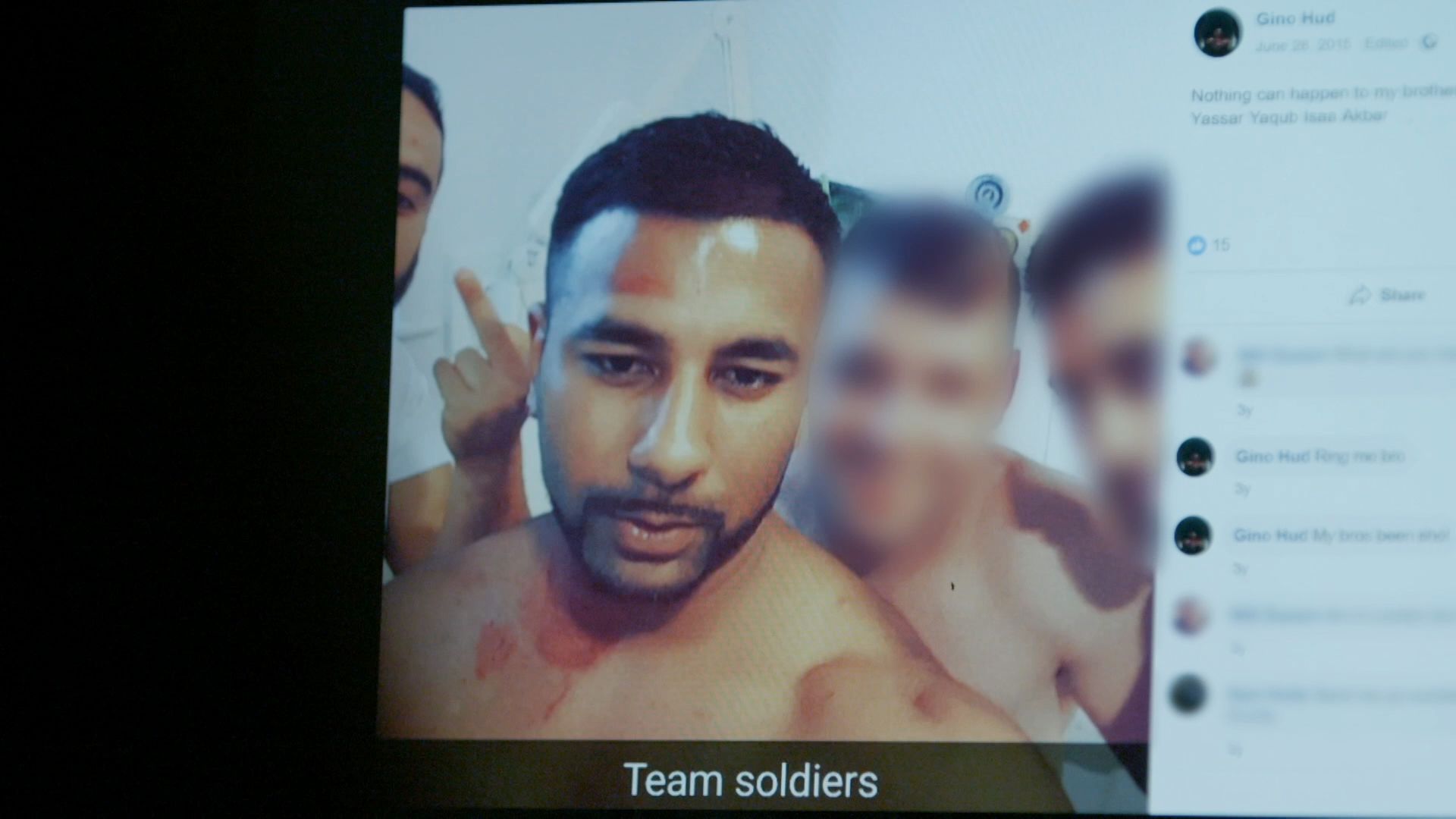

I did some digging and found that Rexhino Arapaj, one of Yassar’s friends who was with him the night he died, had uploaded a picture to Facebook on the same day a shooting was reported on that street. The image featured Yassar splattered with blood with the caption “Team Soldiers”. Arapaj also wrote “my bro got shot”. That post made it look like Yassar had been involved with at least one of the recent shootings. But what kind of “team” had he been on? And if Yassar’s friends saw him as a “soldier”, what kind of war was he fighting?

A post on a friend's social media suggested Yassar had been shot before

A post on a friend's social media suggested Yassar had been shot before

Twenty miles down the road from Yassar’s home, at Leeds Crown Court, Arapaj and Yassar’s two other associates were standing trial. Their first day in court was 13 November 2018. Every day, Yassar’s dad, Mohammed, sat directly behind me and every day, first thing in the morning and when court adjourned, I would ask him for an interview. Initially, he’d tell me to “call him later” or suggest he would “speak to me in a few days” but as details of Yassar’s life came out in court, it seemed like his dad no longer wanted to speak to me.

The prosecution lawyer pointed out that the men on trial had responded “no comment” to many of the questions put to them just after their arrests. Butlin and Amin both said that they had just seen their friend shot and killed and their answers were “down to shock”. But in court, when the prosecution asked Amin if Yassar Yaqub was a drug dealer, he responded, “Yes. He sold drugs.”

This was just one of a series of revelations about the life Yassar was living. A machete and body armour were found by the police in his bedroom. A gun, ammunition and a silencer were in the footwell of the car Yassar was travelling in when he died. The suggestion of criminality was clearly more than just a rumour.

The 'kingpin'

As the scale of the violence across Huddersfield started to sink in, it became clear that Yassar's death was part of a bigger story. To get to the bottom of it all, I realised I needed to do more than rely on courtroom revelations. I started making contact with people at all levels of the drug trade in and around Huddersfield, from drug users to kingpins, to find out what they knew about Yassar.

“The beef now is mainly cos of drugs,” a teenage dealer told me. “That’s what’s causing all the shootings, stabbings. Huddersfield is a small place, so anywhere you go you’re gonna see someone you got a problem with.”

I saw first-hand the role young British Pakistani men were playing in the West Yorkshire heroin trade. According to one source, it was quite common for dealers to go straight from selling drugs, over to their local mosque, then back out on the street after prayer to carry on their business. I even heard anecdotes about wholesale heroin prices going up around the Muslim holy month of Ramadan as dealers put their business on ice.

One of the worst things I heard was that some people justified selling drugs because their customers weren’t Muslim. “In the Hadith [a major source of religious law and moral guidance for Muslims] it pretty much says that if they’re not Muslim you don’t have to respect them,” a dealer, who knew Yassar, told me. “You don’t have to do for them as you do for your brothers and sisters 'cos they're people not of God.”

When I asked the people I met about the morality of dealing drugs, over and over again I heard the same pathetic excuse: “They’re going to buy it from somewhere so it might as well be me.” Their lack of empathy made me sick. The quasi-justifications and references to religion seemed to just be a cover for greed. The human cost of dealing was ignored.

Angie, a drug user since she was 15, has struggled with homelessness

Angie, a drug user since she was 15, has struggled with homelessness

According to a recent report, almost one in every 100 people in Yorkshire and Humber has used crack cocaine and other opiates. That’s one of the highest levels in the country. By 2017, drug-related deaths in the area had risen by more than 75% in six years. That year, there were more drug-related deaths per year in Yorkshire and Humber than in London.

A Freedom of Information (FOI) request revealed that while British Pakistanis make up just 5% of the urban population of Yorkshire and Humber (according to the most recent census in 2011), in 2016/2017 they accounted for 27% of convictions for possession with intent to supply class A drugs. Of course, the majority of convictions in that 12-month period were among the white British community but that is expected, given that white British people make up the vast majority of the population of the area.

So, why were British Pakistanis seemingly so over-represented when it came to convictions for dealing class A drugs?

As I tried to understand the reasons behind this, the name Yassar Yaqub started coming up again. One man I made contact with told me Yassar was a “kingpin”, known as “Biggie” in Bradford, who he claimed he had “delivered kilos” to in the past.

The street value of one kilo of heroin is £100,000.

“He was alright,” my source said of Yassar. “He would help ya, you know what I mean. But if you got beef with him - run basically.”

The claim that Yassar was dealing in large amounts of heroin was backed up by multiple sources I spoke to.

Double lives

In December 2018, the man driving the car in which Yassar was shot, Mohsin Amin, was sentenced to 18 years in prison. Despite all the evidence - the machete and body armour in Yassar's bedroom, the gun found in the footwell of the car and the confirmation in court that he was a drug dealer - Yassar's dad still denied that his son was a criminal.

Mohsin Amin, was sentenced to 18 years in prison

Mohsin Amin, was sentenced to 18 years in prison

It's completely possible that Yassar was leading a double life and his family knew nothing about his involvement in the drugs trade. I wanted to know just how difficult would it be for a drug dealer to hide their business from their parents?

I met up with Naz, a convicted heroin dealer turned youth worker from Bradford. By the time he was 22, he was driving an expensive car and buying all the designer clothes he wanted. His mum thought he was leaving the house to go to a regular job each morning. “If you want to keep something hidden, truly, you can,” says Naz. It was only when he was arrested and eventually convicted that his mum found out where his money came from. The shame of having a son who was a drug dealer was like a “bullet in the head”, says Naz.

Former drug dealer Naz says his mum was deeply ashamed when he got arrested

Former drug dealer Naz says his mum was deeply ashamed when he got arrested

The idea of shame, dishonour or "besti", as it is referred to in South Asian cultures, is something I often heard about when speaking to dealers and their families. That was the case for Tanvir, a shopkeeper who also runs a boxing club in the middle of Girlington, a predominantly South Asian part of Bradford.

We spoke about the older generation’s work ethic and how most Pakistani immigrants had come to Britain to work hard and make a better life. Tanvir told me the first generation of immigrants “are ashamed of younger people” who are involved in drug dealing and criminality.

Tanvir set up a boxing gym in Bradford to try and keep kids off the street

Tanvir set up a boxing gym in Bradford to try and keep kids off the street

The vast majority of British Pakistanis are law abiding people. There is a tangle of factors driving some men in the community to turn to dealing. The first is cultural. In many Pakistani households (and I know this from my own upbringing), boys are raised and treated like princes. They are free to come and go as they please. They are pampered by their mums and few questions are asked about how they spend their time outside the home.

At the same time, many of these boys are taught that, as men, they must be the breadwinner. That the measure of a man is his ability to provide for his family, not in the context of nurturing kids or being a homemaker but, explicitly, and often exclusively, as the financial provider. This is a long-standing cultural norm but, in modern Britain, where youth unemployment in areas like West Yorkshire is a significant issue, this pressure can have unexpected consequences. One man told me: “I respect a man who provides for his family, however he’s making his money.”

This brings us to the second factor: economics. British Pakistanis are entrepreneurial people. When the community arrived in the UK many people set up takeaways and corner shops. Some worked in manufacturing and did many of the jobs working class white people no longer wanted to do. That was back in the 60s and 70s. Three generations later, most of the manufacturing jobs no longer exist. If you’re a young Pakistani man wanting to make money quickly, selling drugs might seem like an option.

Many of the manufacturing jobs in West Yorkshire have vanished

Many of the manufacturing jobs in West Yorkshire have vanished

Add to the mix the fact that the British Pakistani community maintains strong links with its country of origin. Trade between the two nations is worth almost £3 billion today. That trade can, and often does, provide cover for those who want to bring heroin into Britain. Car petrol tanks and baby powder bottles are two methods I heard about from drug importers during my investigation. The majority of the world’s opiates come from the poppy fields of Afghanistan, separated from neighbouring Pakistan by a porous border. Heroin can be shipped from the Pakistani port city of Karachi.

It was no surprise then that all the dealers I met, including the high-level importers, told me the bulk of the heroin they sell comes through Pakistan.

So, was the drugs trade just a well-kept secret in my community or was something else going on? It seemed clear to me that, until we tackled this problem, the drugs-related violence in my hometown was only going to get worse.

Time to talk

Even before I returned to Huddersfield to begin working on this story, I was aware that many British Pakistanis didn’t want to talk about these type of issues for fear of the far-right capitalising on any perceived wrongdoing among our community.

This fear stems partly from the actions of groups like Britain First and the English Defence League, which have used news stories to push an anti-immigrant, anti-Pakistani, anti-Muslim agenda. These groups pedal the “We are not racist” mantra, instead suggesting their only issue is with “Islamisation”. They will twist headlines to back up their view of our community. As more than a few people in Huddersfield told me: “They act like we’re all either terrorists or groomers.”

I’m aware that those with an agenda will delight in adding drug dealing to the list of wrongdoing and could use it to stoke racist sentiments against my community. But that should not stop us from talking, asking questions and looking for solutions. So many of my peers are, in my opinion, fixated on media bias and the far right. We are hyper defensive with so much energy going into establishing that we “are not all bad” that the possibility that a problem exists can be overlooked. In many circles, the conversation has stalled. That’s not helpful.

That refusal to engage with the reality around us reminds me of the Justice 4 Yassar rally I attended at the start of my investigation. I now understand why so many people there were reluctant to talk to me beyond reeling off lines about Yassar being a “great guy”.

Since then, it has been established in court that Yassar Yaqub had gone to Bradford to meet a drugs kingpin on the day he died. The meeting is believed to have been about a drugs dispute. It also emerged that, shortly after police forced the car Yassar was in to come to a stop, a plain-clothes officer opened fire and as a result, Yassar lost his life. A gun, along with a silencer and ammunition, was recovered from the car Yassar was in.

For any life to end in this way is tragic. Yassar was a dad and a much-loved son. He left behind an entire community that has struggled to process the significance of his life and how it relates to his death.

In an attempt to reach out to the community, I asked a local radio station if I could make an appearance on one of their shows. I hoped a phone-in might shed some light on what other Pakistani people in the neighbourhood thought about the issues I'd been investigating.

One caller, living in the Birkby area, said they thought local people were “fed up” and wanted issues around violence and drugs “to be sorted”. He pointed out that it’s not just Pakistani people who are involved, but said: “You’ve got to be honest and you’ve got to tackle it within your own community. You can’t hide behind the fact that other people are also doing it, but I think a lot of families are burying their heads in the sand”.

Discussing whether or not there had been a rise in violent crime in the Asian community, another local caller, in my view, hit the nail on the head. He said that “disproportionate” reporting of crimes by Asian people can put the community “on the defensive”. However, he added: “Then, the problem that we have is that we have our focus on being negatively portrayed in the media - but then the problem itself is brushed aside”.

If any good can come from what happened, it is the acceptance that the only way forward is through talking. Those conversations can be painful. They can be riddled with shame. But, if things are going to change, these conversations need to happen.

Hometown: A Killing is available to watch on BBC iPlayer, or catch episode two on 26 June on BBC One at 10.40pm.

If you have been affected by any of the issues raised in this article help and support is available.

Credits

Author: Mobeen Azhar

Editor: Serena Kutchinsky

Designer: David Weller

Researcher: Hannah Price