Searching for the missing girl

When one man made a rash promise to help a friend in trouble, he triggered a chain of events involving betrayal, disappearance, and a mother’s desperate attempt to find her child.

The story begins with Rob Lawrie, a former army fitness instructor and the owner of a carpet business in Leeds.

In September 2015 the world was shocked by pictures of a Syrian boy, Alan Kurdi, who had drowned in the Mediterranean and been washed up on the shore.

There was something about that perfect little body, fully clothed, lying like a piece of flotsam on the sand. Lots of people were shocked, but Rob couldn’t shake the image off.

“I started imagining what his last two minutes of conscious life must have been like,” he says. “He’s rolling around, getting tossed around in that sea, probably wondering where his mummy and dad are. It’s unimaginable, isn’t it?”

The image of a child alone resonated deeply for Rob. Although he was living comfortably in a house near Leeds, with his wife and children, in his teenage years he had been brought up away from his own parents, in a children’s home.

With money he’d won from a TV game show, Rob decided to see if there was anything he could do to help others like Alan. In the autumn of 2015, he set off for France in his van to the Jungle, a sprawling makeshift refugee camp, stretching across sand dunes on the edge of the French port of Calais.

Rob Lawrie

Rob Lawrie

At the time, it was home to about 6,000 migrants from 25 countries, all sheltering under tarpaulins in what they hoped would be the last stage of a desperate journey to Britain.

Although Rob only planned to go to the Jungle for a few days, he kept on returning.

I remember my own first impressions of the Jungle, passing columns of refugees trudging along dusty tracks criss-crossing the camp. It was noisy, scary and lawless, and it stank to high heaven because there was no sanitation.

There was a makeshift library, a mosque, churches, shops and even small cafes and restaurants.

Teams of volunteers tried to build a sense of community amid the squalor. Rob stood out, a six-foot-two Englishman, always wearing a red Stetson hat. He’d worn it on the TV game show - it was his lucky charm.

It was here that he met Reza and his little girl, Bru. In halting English, Reza told Rob his story. He said he had fled from Afghanistan, where he was being persecuted by the Taliban. He showed Rob what he said was a death threat that had forced him off his land.

Reza had escaped, but he told Rob that his wife hadn’t been so lucky. He believed her to be dead, and said that their baby son was being cared for by relatives. He was desperate to get to the UK to give Bru the chance to forget and to live a better life.

They lived in a small tent strung between trees - when it rained, water would come through the plastic and drench their pillows and blankets. It smelt of damp and it was hard to stay warm, even with the extra clothes that were donated. There was no electricity and their water came from one of the central points on the camp.

Deeply moved by the plight of this little child living in appalling conditions, Rob was persuaded to try to smuggle Bru and her father to England. Reza said he had distant relatives in Leeds who would look after them.

It was a moment of madness but it made sense to Rob, who felt sympathy for the little girl who followed him round wanting to play. He was moved by Reza’s stories of Taliban attacks directed at women and girls, and knew the lengths he’d go to protect his own daughters. But whatever his motive, his efforts were clumsy.

The original plan was to hide both Reza and Bru in his van. Late one night, after Bru had fallen asleep by the campfire, Reza and Rob carefully lifted her into a small sleeping compartment above the driver’s cab. However, there wasn’t enough room for Reza. Rob thought that meant abandoning the whole idea, but Reza argued that he could stay behind and pay smugglers to get him to the UK as soon as he could.

He kissed his daughter goodbye and told Rob that relatives would call him and arrange to collect Bru when they reached Leeds.

The plan was foiled when sniffer dogs on the French border raised an alert. Rob’s van was searched and police found two Eritrean refugees hiding under clothes in the back. Rob had no idea how they’d got there and the authorities believed him. But then he told them about Bru, who was still undiscovered in the sleeping compartment.

Rob says he realised too late that he should never have allowed Reza to persuade him to do what he did. He was arrested and faced a five-year prison sentence for people-smuggling.

I was one of many journalists who attended Rob’s appearance in a Boulogne courtroom.

Reza came to court with him and even tried taking responsibility for what had happened, telling police that Rob hadn’t been aware of the plan.

Perhaps the influx of media, and the widespread sympathy for Rob, made the court more lenient than it would otherwise have been. He was cleared of the serious charge of people-smuggling, but given a suspended fine for endangering a child’s life by letting Bru travel without wearing a seat belt.

So it wasn’t a total acquittal. Rob was made to look naive. His wife was furious and felt let down that he hadn’t consulted her. She left him, taking the children with her. His carpet-cleaning business hadn’t been going so well either, with its owner away for so long.

Reza and Bru went back to the Jungle and Rob returned to the UK. He worked with me on a radio programme about his experiences, Child Rescue.

Then, a few months later in October 2016, the French authorities started to bulldoze the Jungle, and Rob got back in touch with me.

The mobile number he had used to stay in touch with Reza and Bru had gone dead, and Rob was worried about them.

Thousands of migrants were being rounded up and offered places in different centres across France. Many had disappeared, fearing that being fingerprinted in French asylum centres could reduce their chances of settling in the UK.

We headed to Paris and picked our way through the brightly colored tents stretched out along the Avenue de Flandre and around the Jaurès and Stalingrad Métro station, speaking to refugees sleeping out. But we didn’t find Reza and Bru.

2017: A migrant camp on the banks of the Canal Saint-Martin, Paris

2017: A migrant camp on the banks of the Canal Saint-Martin, Paris

That might have been the end of the matter. However, two events brought the story back to life.

The first was a script from a Hollywood film director who had visited Rob shortly after his arrest. It would tell the story of two fathers, Reza and Rob, and the friendship between them.

The director told me he planned to cast Rob as a modern-day cowboy, tall and purposeful as he strode through the Jungle in his Stetson. Rob thought that money from the movie might help Reza and Bru - if only we could find them.

Then there was an email which changed everything we thought we knew about the story of the father and daughter.

I occasionally called in to see Rob when I was visiting my father in Leeds. It was on one of those visits that the email pinged on his phone.

Rob was still receiving hundreds of messages about the little girl he had tried to help, and I assumed it was another person offering to help or wanting to find out what had happened to the four-year-old.

But this was from a volunteer working with refugees in Denmark. Martin Westergard said he had met a woman called Goli, who claimed to be Bru’s mother. Far from being dead in Afghanistan, she was very much alive and searching for her daughter.

“I know that you have probably met hundreds of asylum seekers and that you maybe have no contact with Bru and Reza,” he wrote. “In any case I promised Goli to at least ask you the question, ‘Do you know if Bru is doing well? Is she alright?’”

According to Goli, Reza was not fleeing the Taliban in Afghanistan. He was not the bereaved father he had claimed to be, nor was he a political refugee.

Reza had been born in Afghanistan but had moved to Iran as a child, and was living there with Goli and their two daughters. He had deserted his wife and new-born baby, taking Bru with him, in search of a new life in the UK.

If what Goli was saying was true, Rob had risked everything - his own marriage, his family life and his freedom - to help a man who had lied to him.

A mother's journey

We find Goli in a dilapidated former nursery school in Denmark, housing refugee families. As we approach, a little girl runs over and grabs my leg. Looking down, I see Bru’s double - the same deep dark eyes, impish grin and jet black hair.

Goli herself is a beautiful young woman, dressed in a loose wrap-around skirt and T-shirt, her long wavy hair pulled away from her face. She tells us she has just started studying on a pre-degree course. But she has overcome many obstacles to reach this point.

She introduces us to her daughter, Baran, and starts to tell her story of how Reza betrayed her.

Reza and Goli had been living a settled family life in a leased flat in the Iranian capital, Tehran.

He was happy when Bru was born, but he was definite about not wanting a second child. When Goli became pregnant again, Reza was furious, and she feared he’d leave her. Under their marriage contract, he would only be obliged to pay her 70 gold coins, or around £7,000, if they separated.

However, in the event, she says that Reza just disappeared with Bru while she was away with the baby visiting relatives.

One of Reza’s relatives told her that they’d set off for Europe. As Goli tried to process things she felt an almost animal-like instinct taking root amid the hurt and upset.

“I couldn’t breathe. I told my sister I thought I couldn’t tolerate it. I thought I might die,” she says.

“I just lost my heart. I thought I was being choked. That I couldn’t survive. Sometimes when I think of it, I think I’ll never forgive this man. For the first time my feeling as a mother gave me a very powerful feeling. I went to the police station, to the court, I went everywhere.”

Goli thinks Reza had set his sights on reaching the UK because he’d seen relatives go there and earn a lot of money.

“His aunt there sent very expensive gifts, beautiful presents,” she says. “His brother was in the UK, and when he came back to Iran to see the family he brought iPhones and laptops for Reza. The brother said, ‘Forget your woman. If you want to come I will make the plan.’”

Goli says in her community, women have little say. She led a very traditional life as an Afghan-born refugee in Iran and didn’t even have her own bank account. “I didn’t have any freedom in my house. I was a very simple, naïve woman and I felt I couldn’t do anything.”

When he disappeared, Reza changed his phone number and only contacted her once. On a crackly phone line, he called to say he was in Turkey with Bru.

“I said to Reza, ‘Just come back with Bru. Don’t destroy everything.’ He said, ‘I can’t have that life in Iran. I just want to go and settle somewhere.’ He said he had brought Bru to make it easier for him to get asylum.”

Goli: “Sometimes when I think of it, I think I’ll never forgive this man”

Goli: “Sometimes when I think of it, I think I’ll never forgive this man”

Reza promised Goli that once he got asylum in the West he would send for her and the baby.

“After that he didn’t call me,” she says. She moved in with Reza’s family, who had a big house. But Goli and her baby were given a very small room.

She also began to distrust the family.

“I could hear Reza calling his sister and his mum, but he wouldn’t call me or speak to me. He wouldn’t let me speak to Bru. I heard his mum talking to Bru and realized something was very wrong.”

As a deserted wife, Goli had no status or rights in the eyes of her husband’s family. She feared a day would come when Reza’s parents would try to take Baran from her, and make Goli leave their home. After a few months her own relatives put together some money to help her try to follow Reza to Europe.

It was a highly dangerous journey for a lone woman with a small child. Goli says she travelled mainly at night, often on foot. She headed first over the mountains to Turkey where her mother and sister lived.

“It was very hard, the weather was so cold,” she says. “I was alone and [the smugglers] can do anything they want with you.“

By the time she reached her mother in Turkey, she’d already travelled over a thousand miles in the search for her daughter. Her mother wanted her to stay and rest, but she was determined to press on.

She paid smugglers for a place in a dinghy going from Turkey to Greece.

Goli was terrified. She was ordered onto an overcrowded boat with people she didn’t know or trust, and given an inner tube as a buoyancy aid if they sank. But there was nothing for Baran, and as they pushed off into the cold waters of the Aegean, Goli gripped her tight and prayed.

The wind and rain battered the boat and in the darkness she thought she could make out the lights of a Greek island as they neared. But then fighting broke out and the boat capsized. Although the water was shallow Goli lost hold of Baran and couldn’t see her.

With tears streaming down her face, Goli tells us it was the most frightening moment of her life.

Luckily, another refugee caught Baran and held her up, asking, “Whose is this baby? Whose is this baby?”

From Greece, Goli travelled in the back of lorries or without tickets on buses and trains through Serbia, Hungary, Austria and Germany. She was frightened, hungry and cold, and had little sense of where she was.

Heading north, she found a group of other refugees to travel with but they parted ways in Denmark. Here, Goli’s journey was cut short because Baran was sick and needed emergency medical care.

Goli was given a place in an asylum centre and was told that she would need to lodge a claim for asylum in Denmark, because it was the first safe country she’d stopped in during her journey. It is hard to get refugee status in Denmark, with less than 10% of cases succeeding. Goli did eventually, because she could support her case with documents from Iran relating to the disappearance of Bru.

Goli went to the Danish police to try to get help. A translator helped with a statement and photos, but the police said they couldn’t act because any offence had taken place in Iran.

Months later, that translator was reading a BBC report about the Calais Jungle, and saw photos I had taken of Bru. He instantly recognised her and called Goli.

That led her to us - a remarkable chance encounter that set in motion our efforts to track down Reza and to try to reunite Goli with Bru.

The documents she had in her possession seemed to support her story, but we couldn’t hear Reza’s side until we found him and it seemed he didn’t want to be found.

Goli sent the Red Cross the news reports about Rob Lawrie’s trial and waited.

The charity confirmed that Reza and Bru were still in Calais and said if Goli sent them photos of herself they would try to pass them on to Bru - but only if Reza agreed.

Goli waited and heard nothing back. And then came a very important letter from the Red Cross - Reza and Bru were thought to have made it illegally into the UK although no-one knew where they were.

The search for Bru

We begin our search for Reza and Bru by looking for Reza’s cousin or any of the other relatives Goli thinks are in the UK. To no avail. So we turn to social media.

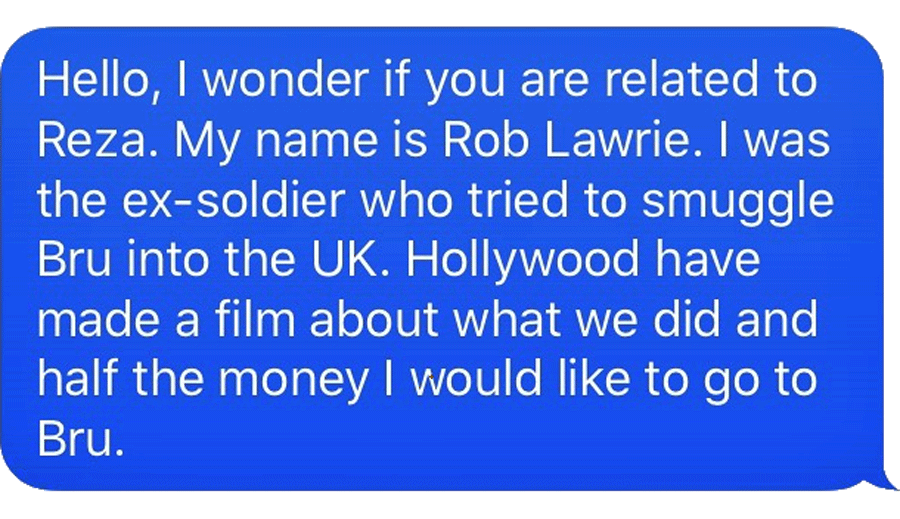

Rob has a huge following since his arrest in Calais, and he posts a message on Facebook, trying to encourage Reza to make contact.

The message includes a link to news about the planned Hollywood movie and the thousands Rob is set to receive. He has always said he would help Bru, and perhaps Reza will believe him.

We receive a response from someone claiming to be a relative of Reza’s, asking about the money. Is it Reza himself? We give little away.

After a few hours, Rob receives a text from an unknown number.

Rob replies straight away.

The reply is instant - a thank-you and a sign-off. We’re certain it’s Reza.

Rob replies:

Seconds later a reply.

“We must talk.”

Rob: “Yes of course we must.”

The text exchange continues and then comes this reply: “See you in UK.”

Rob: “Are you in the UK?”

A message comes straight back.

“No.”

Rob: “I can’t help you if we can’t talk.”

The minutes drag on and then a final text before the contact stops.

“Thank you, I don’t need help.”

We want to hear his account of what had happened - why he’d apparently lied to Rob, why he had taken his own child from his wife and taken her on a perilous journey to Britain - but he doesn’t want to talk to us.

And if he is the liar that Goli suggests, then knowing that we are on to him might make him go further underground and expose his young daughter to more danger and disruption. So we decide to investigate other options.

We contact a lawyer, Anne-Marie Hutchinson, who agrees to contact the Home Office using the different names that Goli suspects Reza might be using. She has a series of identity cards from Iran and passes these to the lawyer.

Anne-Marie is also the chair of the government-funded Reunite International Child Abduction Centre, and she’s noticed something that troubles her - the number of male refugees arriving in Europe with no wife and only one child. She wonders how many have used these children as a passport into Europe.

Weeks later she calls to say that her searches at the Home Office have drawn a blank.

Meanwhile, the texts start up again.

Reza says he wants to meet, but it has to be at an out-of-town shopping centre at an address in Scotland, and he can only come late at night.

The tone of the messages worries Rob. Could it be a plan Reza is putting together with his brothers? We counter with a compromise - we will meet in the shopping centre, but in daylight. An arrangement is made.

We plan to meet in Starbucks, and spot Reza nervously looking through the window. He has on a baseball cap pulled low and a blue raincoat. He paces back and forth a couple of times and then comes in, smiling and walking straight to Rob.

Picture secretly taken by the author, shows Rob (sitting, far right) reunited with Reza (blurred) in Scotland; Bru (also blurred, centre) sits at a separate table

Picture secretly taken by the author, shows Rob (sitting, far right) reunited with Reza (blurred) in Scotland; Bru (also blurred, centre) sits at a separate table

Reza tells him he’s in the process of finding a new place to live in Leeds and that he has been given the right to remain in the UK by the Home Office. In his own words he confesses to having “cut a limited story” to immigration officials.

And then we notice a little girl standing a few yards away. She looks so familiar. She’s seven now and has changed so much from the spirited four-year-old who followed behind Rob as he built camps for refugees.

As she comes closer to Rob, a look of recognition seems to pass over her.

Reza beckons her over and says that she has forgotten her mother tongue. She’s assimilated into her new life well. She speaks better English than her father and laughs as Rob teases her about her accent.

She’s a beautiful little girl, so chatty and eager to recount details of her life in the UK, her school, the friends she’s made and the awards she’s got for good behaviour.

Eventually, the meeting is over. We can’t stop Reza and Bru disappearing into the crowd. It seems that Reza has only met us because he thinks he’s getting money from the Hollywood movie.

It doesn’t feel safe to confront him about the lies he’s told us. We need to know more about his circumstances if there is to be any hope of a reunion between Goli and Bru.

Before they go and without Reza noticing, I quickly pull out my phone and take a couple of photos of Bru to give to her mother. These will be the first images Goli has seen of her child since those pictures on the BBC website three years before.

When we phone Goli with news that her daughter is alive and well she breaks down, unable to contain her relief. As we speak we send our photos to her phone. She begs us to kiss her daughter, to hug her daughter and to make a plan for them to be reunited.

So much is at stake and we don’t want to scare Reza off. We need a way to find out where he is living.

Tracking Reza

It’s 19 December, and I’m sitting in my car, in the dark, stuffing a small tracking device inside a soft toy.

Rob has sent a text to Reza asking to meet again, this time while Bru is at school. We know he’ll think it’s about the Hollywood money, but there won’t be any. Instead Rob’s bought him gifts - a baseball cap and a teddy bear.

I had noticed in the shopping centre that there was a Build-A-Bear shop. They come with a seam left open, so you can put little personal things inside and pull the threads tight.

The tracker is linked to an app, which will show its location. If Reza takes the bear with him, it will lead us to where he and his daughter are living. We have agreed to disable the tracker the moment it gives us his address. Whatever happens, it will be disabled before Bru returns from school.

Sue Mitchell tells the story of a hunt across closed borders and broken promises, in search of a lost child - and the truth.

Girl Taken is a BBC Radio 4 podcast

A private detective who has been helping us, suggests someone also follows Reza on foot. Rob’s friend Colin agrees to help.

We’re meeting in another out-of-town shopping centre. I’m in place across the road watching from a shop window, Colin is at a back table in the coffee shop and Rob waits near the entrance ready to greet Reza.

Reza is late and we fear he might have got wind of what we’re up to. When he arrives he paces back and forth outside for a few minutes, but then he enters, smiles and accepts the bear from Rob. He’s keen to talk about his life in Afghanistan and the war he claims he fled.

After about 20 minutes, he gets up to leave. He has the bear with him, and Colin is on his trail. This is it.

Back at the car we watch the tracker as it refreshes every 20 seconds. Colin phones in his location as he follows Reza on and off buses. But then Colin calls in a panic - he fears Reza’s onto him. He’s spooked and wants to fall back, leaving us reliant on the tracker. We agree, but then the tracker suddenly stops moving.

Twenty minutes pass. We fear Reza might have abandoned the bear in the bus station. Colin comes back to the car and relays a journey in which Reza appears to double back on himself - is he trying to throw us off track?

It’s a nerve-wracking moment and we feel deflated. Reza is unlikely to meet us again and if this doesn’t work there isn’t a back-up plan.

The private detective who has been helping us, volunteers to head towards the last location point on the app. We wait and time seems to slow down.

Then everything happens at once.

The app bursts into life, the bear is on the move and the detective is on the case.

We chart the route as it snakes out from the city centre.

Then comes the moment we’ve been waiting for.

The detective phones. He’s outside a block of flats and has seen Reza going into the building just seconds before.

The detective suggests we look for clues to confirm that Reza and Bru live there. And that means sifting through rubbish bags outside the building. It’s a slow and unpleasant job, but we find a child’s bus pass and a school label with Bru’s name on it.

We phone Goli with the news - we have found her little girl.

Reunion

We are now able to hand matters on to the authorities. Subsequent checks with the Home Office reveal that Reza appears to have entered Britain with a similar story to the one he told in France - a story at odds with the documents and information provided by Goli. An investigation is launched to get to the bottom of the claims made during the asylum process.

During the course of the investigation, we try to contact Reza to check on the welfare of Bru and to hear his explanation for his actions. To date he hasn’t responded.

We’ve reached a part of the story where respect for a little girl’s privacy means we won’t be able to reveal the rest of what happens in so much detail, but an ending of sorts is in sight.

Goli receives help from Angus MacNeil, a Scottish National Party MP, who has taken a particular interest in refugee issues. He agrees to start informal negotiations with Reza about giving Goli access to Bru.

Through talking to MacNeil, Goli accepts that whatever Reza has done, he’s the only parent Bru has known for more than half her life. “We need to think about what is best for the girls - and to let both sisters know the father and both sisters know the mother,” says the MP.

What happens longer term will be up to the authorities and is complicated by the fact that Goli has refugee status in Denmark. There is no automatic right for her and her younger daughter to settle in the UK even if she wanted to.

It’s just before Christmas and Goli and Baran have arrived at Liverpool Airport with a bag brimming with presents.

Rob and I pick them up and immediately Baran shows us her new swimsuit. Goli has brought the exact same one for her sister, but confesses that she didn’t know what size to buy. Bru was taken when she was three, and is now eight years old.

Messages are pinging on Goli’s phone, from her mother in Turkey and from Martin, the Danish refugee worker who has helped her so much. They’re praying that things go well.

As we drive to the meeting point, we spot Bru walking alongside her father, carrying her own bag of gifts for her sister. After all this time, Goli struggles to recognise her daughter by sight and breaks down. She can’t really believe this day has come. I hang back, not wanting to intrude on this very private moment.

Goli has been preparing herself for this day. She knows it will not be easy and she has to take a few moments to hold her emotions in check. She is nervous as she approaches Bru and senses the confusion as the little girl watches her approach. She stops herself and bends down, introducing herself - by name - to her own daughter.

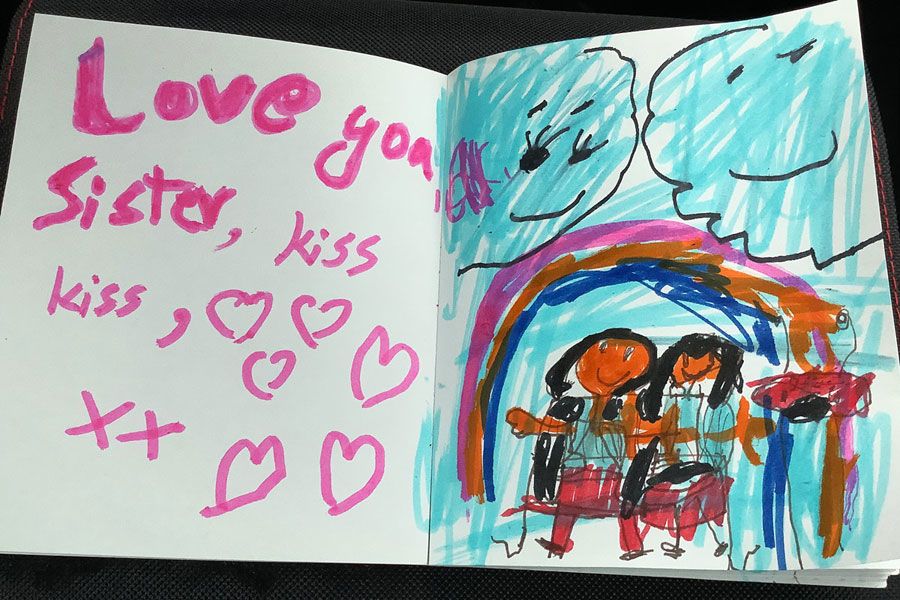

For Baran there is no holding back and her joy is immediate. She runs straight over to her big sister and grips her in a hug, not letting her go. Before the reunion she’d talked of wanting to hug her sister and now her dream has come true. In her excitement she shows Bru her new swimsuit, and talks about how they can swim together in their matching suits.

Goli has been learning English so that she can be confident about talking to Bru, and at first they’re all talking over each other, with Baran's voice winning out.

Then the three of them find a way of connecting, both ordinary and yet so powerful - they brush each other’s hair and Bru gathers her mother’s curls into little bunches.

Midway through that reunion Goli leaves her daughters playing together for a few moments. She calls me and says that the emotions she’s experiencing are so strong that she needs a few moments away to reflect on what’s happening. She doesn’t want to overpower Bru with the force of her feelings and she’s trying to keep the conversation relaxed and upbeat.

When Goli finally returns to the car, after a meeting with Bru lasting a couple of hours, she is euphoric - showing me photos and a video she's taken on her phone of Bru and her sister playing together. She's already sent them to her mother, her sister and to Martin.

She says it felt like Bru had no memory of her and this was hard to cope with: “She was totally unprepared. She doesn’t have any background of her mother. She thinks, ‘My mother is not alive and I don’t have any mother.’

“She tried to come close to me. It was incredible to see her for the first time. I can see how much she’s grown up, how beautiful she is, how independent she is and so I don’t feel too sad. I can forgive something.”

It’s been a remarkable journey for Goli. She describes her past life in Iran as being like a kind of prison, an existence where she had no say or control and where her only joy - her life as a mother - was cruelly ripped from her. She says she has changed so much.

“I didn’t know I had this power inside me. Now the feeling I have as a woman is very good. It’s beautiful. I have choices, and I can take responsibility for my decisions.”

For Goli this isn’t an end - far from it. There is lots of work that must take place to rebuild the relationship she lost.

“That is my dream now, to look after my children. To start to make this relationship. I really want to try and stand up strong. I can give her a beautiful life - she deserves that.”

Although he was so angry at being lied to by Reza, Rob now feels less strongly. He says he can forgive Reza and is sure that over time Goli will be able to rebuild her relationship with her daughter.

Rob has done what he set out to do - intervening very personally in the refugee crisis, in his own small way. However good the systems are for coping with refugees, the authorities can never hope to get to the bottom of all these stories. I’ve learned that, amid the chaos, the truth can be easily obscured.