The Nazi in the family

A BBC News investigation has found that an alleged Nazi war criminal, who settled in the UK, could have worked for British intelligence during the Cold War.

Before he died, German officials were investigating Stanislaw Chrzanowski for the War-time murders of Jewish people and others in Belarus.

He had previously been interviewed, but never charged, by UK police.

Now, Chrzanowski, who had boasted to his stepson he had an “English secret”, has turned up on 1950s film footage from Berlin.

And Jewish leaders are calling for an investigation into whether he, and others like him, were protected from prosecution because they spied for the UK.

By Nick Southall

For more than 60 years, John Kingston suspected his stepfather had been more than just a guard working for the local council in his hometown in Eastern Europe during World War Two.

He became convinced Stanislaw “Stan” Chrzanowski was a Nazi war criminal who had evaded justice. And on several occasions, he tried, but failed, to persuade the UK authorities to prosecute.

John amassed a hoard of evidence – photos, documents and secretly recorded phone conversations. For 20 years, it was stored in his attic.

I got to know John in 2016 and began my own investigations into Stan’s War-time activities. But it was only when John died - and all the material in his attic was gifted to me - that possible new evidence emerged as to why Stan was never charged.

The Nazi

in the family

A BBC News investigation has found that an alleged Nazi war criminal, who settled in the UK, could have worked for British intelligence during the Cold War.

Before he died, German officials were investigating Stanislaw Chrzanowski for the War-time murders of Jewish people and others in Belarus.

He had previously been interviewed, but never charged, by UK police.

Now, Chrzanowski, who had boasted to his stepson he had an “English secret”, has turned up on 1950s film footage from Berlin.

And Jewish leaders are calling for an investigation into whether he, and others like him, were protected from prosecution because they spied for the UK.

By Nick Southall

For more than 60 years, John Kingston suspected his stepfather had been more than just a guard working for the local council in his hometown in Eastern Europe during World War Two.

He became convinced Stanislaw “Stan” Chrzanowski was a Nazi war criminal who had evaded justice. And on several occasions, he tried, but failed, to persuade the UK authorities to prosecute.

John amassed a hoard of evidence – photos, documents and secretly recorded phone conversations. For 20 years, it was stored in his attic.

I got to know John in 2016 and began my own investigations into Stan’s War-time activities. But it was only when John died – and all the material in his attic was gifted to me – that possible new evidence emerged as to why Stan was never charged.

The bedtime stories

John’s mother, Barbara, met Stan in 1954 - at a Polish club in Handsworth, Birmingham. Her head was turned by the handsome foreigner who loved to dance.

Stan told her he had arrived, with other Polish soldiers, in Liverpool, in 1946 – the year after the War ended. And he had been brought up in Slonim – a town in Poland when War broke out but now in Belarus.

Barbara was so taken with Stan she asked him to join her and her two children that summer, on their caravan holiday at Rhyl, Denbighshire .

John, aged nine at the time, called it “the holiday when everything changed”. At first, he was in awe of his new father figure.

“So much about him was fascinating and foreign,” John said.

“I sort of admired him and wanted to be like him.”

Stan told the Kingstons he had worked at a sawmill in Slonim at the start of the War until, in 1943, the Nazis had made him become a civilian guard. He had managed to escape, in 1944, became a prisoner of war, and then joined the Polish military to fight with the Allies.

The family had no reason to doubt the story.

The factory worker moved into the Kingstons’ home, in Balsall Heath, Birmingham.

John as a child

At home, he taught John how to jump off walls like a paratrooper – and bought him a toy German Luger pistol so he could play soldiers in the rubble of the city’s many bomb sites.

But slowly, another Stan started to reveal himself. Young John was affected deeply, both physically and mentally.

“It was a nightmare growing up with him,” he told me. “He was a very dangerous man.”

Stan had a fierce temper and brought pieces of rubber flex back from work to whip both John and the family dog.

“I was covered in welts,” John said.

At bedtime, Stan told John war stories. They were exciting at first but gradually became more sinister.

Stan described horrific events when the Nazis arrived in Slonim. He had spoken about people being tortured and interrogated, John said.

“Sometimes he would talk about babies being grabbed by the ankles and smashed against the corner of a building,” he said.

“And he would demonstrate how it was done.”

Stan said he had seen such atrocities through binoculars. But John told me the stories had been so vivid it was as though Stan had committed the crimes himself.

John with his stepfather Stan and mother Barbara

John’s mental health suffered while living with Stan. And as a young adult, he became desperate to leave home.

At the same time, he began to question Stan’s background. Had his stepfather actually worked for the Nazis?

John eventually met Sheila, whom he married. And they moved to a new life in Holmfirth, West Yorkshire. But their marriage would see terrible heartbreak.

Four of their six children would die young. In particular, the loss of their 17-year-old son Gerry – from meningitis – hit John hard.

Cumulative grief brought him to a point where he found himself overwhelmed by what he felt was a terrible injustice. He believed the only father figure he had known had done terrible things – even possibly to children – yet was free to carry on with his life.

And then, he spotted the chance to do something about it.

The bedtime stories

John’s mother, Barbara, met Stan in 1954 - at a Polish club in Handsworth, Birmingham. Her head was turned by the handsome foreigner who loved to dance.

Stan told her he had arrived, with other Polish soldiers, in Liverpool, in 1946 – the year after the War ended. And he had been brought up in Slonim – a town in Poland when War broke out but now in Belarus.

Barbara was so taken with Stan she asked him to join her and her two children that summer, on their caravan holiday at Rhyl, Denbighshire .

John, aged nine at the time, called it “the holiday when everything changed”. At first, he was in awe of his new father figure.

“So much about him was fascinating and foreign,” John said.

“I sort of admired him and wanted to be like him.”

Stan told the Kingstons he had worked at a sawmill in Slonim at the start of the War until, in 1943, the Nazis had made him become a civilian guard. He had managed to escape, in 1944, became a prisoner of war, and then joined the Polish military to fight with the Allies.

The family had no reason to doubt the story.

The factory worker moved into the Kingstons’ home, in Balsall Heath, Birmingham.

John as a child

At home, he taught John how to jump off walls like a paratrooper – and bought him a toy German Luger pistol so he could play soldiers in the rubble of the city’s many bomb sites.

But slowly, another Stan started to reveal himself. Young John was affected deeply, both physically and mentally.

“It was a nightmare growing up with him,” he told me. “He was a very dangerous man.”

Stan had a fierce temper and brought pieces of rubber flex back from work to whip both John and the family dog.

“I was covered in welts,” John said.

At bedtime, Stan told John war stories. They were exciting at first but gradually became more sinister.

Stan described horrific events when the Nazis arrived in Slonim. He had spoken about people being tortured and interrogated, John said.

“Sometimes he would talk about babies being grabbed by the ankles and smashed against the corner of a building,” he said. “And he would demonstrate how it was done.”

Stan said he had seen such atrocities through binoculars. But John told me the stories had been so vivid it was as though Stan had committed the crimes himself.

John with his stepfather Stan and mother Barbara

John’s mental health suffered while living with Stan. And as a young adult, he became desperate to leave home.

At the same time, he began to question Stan’s background. Had his stepfather actually worked for the Nazis?

John eventually met Sheila, whom he married. And they moved to a new life in Holmfirth, West Yorkshire.

But their marriage would see terrible heartbreak. Four of their six children would die young. In particular, the loss of their 17-year-old son Gerry – from meningitis – hit John hard.

Cumulative grief brought him to a point where he found himself overwhelmed by what he felt was a terrible injustice. He believed the only father figure he had known had done terrible things – even possibly to children – yet was free to carry on with his life.

And then, he spotted the chance to do something about it.

‘Do you know a war criminal?’

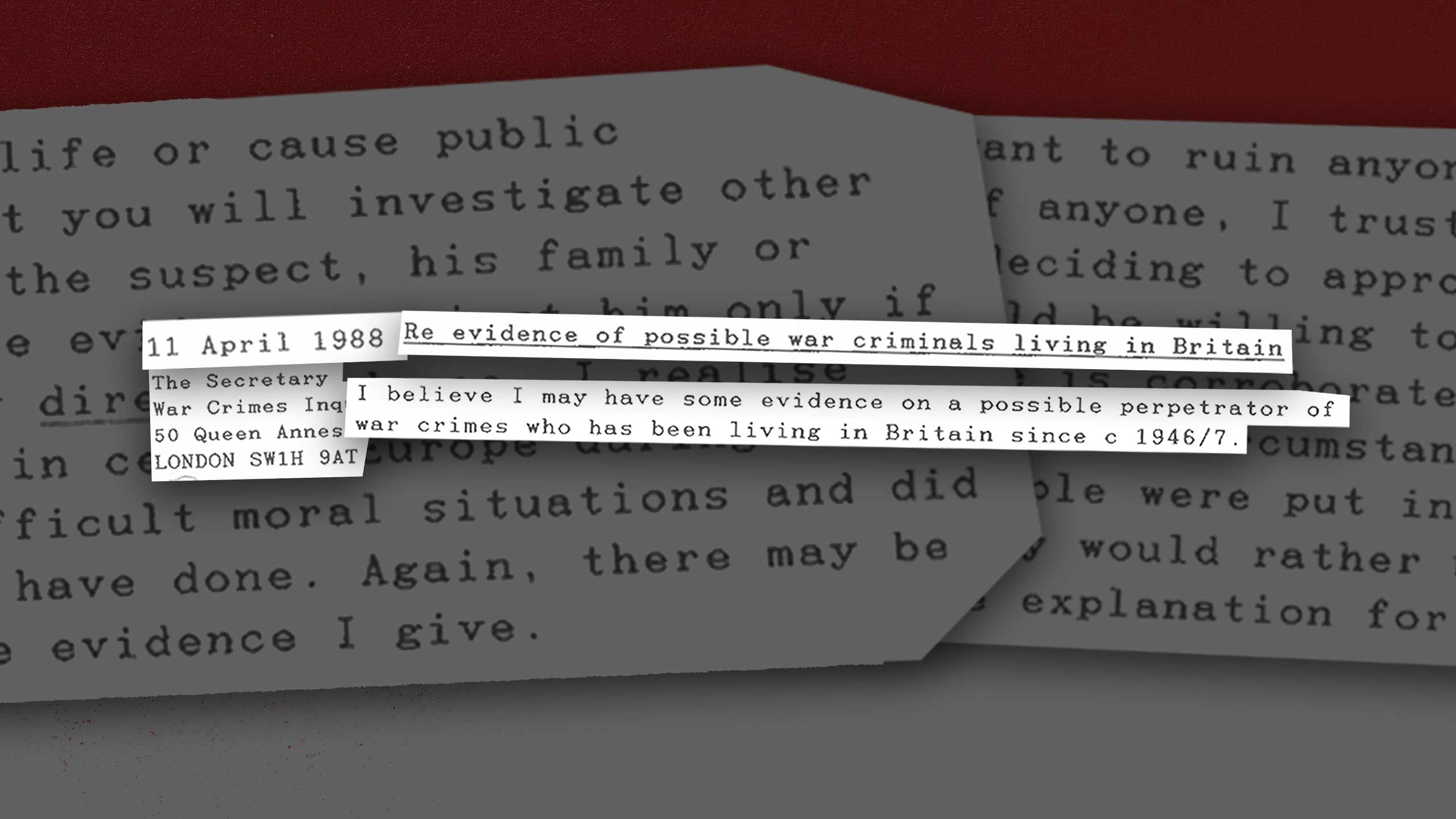

In March 1988, John saw a notice in a national newspaper.

It was asking for information about alleged criminals living in the UK who had been responsible for “genocide, murder or manslaughter in Germany or German-occupied territories” in World War Two.

The government had set up an inquiry after being given a list of suspects by Nazi investigators at the Simon Wiesenthal Center.

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher said at the time, according to security expert Prof Anthony Glees, failing to check the men’s backgrounds at the end of the War made the UK “look like a [Latin American] banana republic”.

John was convinced Stan was one of the men who had slipped through the net – not “just a guard” for Slonim’s local council, as he had claimed.

He wrote to the inquiry outlining the dreadful things Stan had told him. Letters passed back and forth. And police officers interviewed Stan. But John was told “no further action” would be taken because of a lack of evidence.

Stan now knew about John’s suspicions and had clearly been spooked by the police questioning. He applied for travel visas to Russia, Poland and Canada, where he had War-time friends and relatives.

And as wider police investigations continued, three of Stan’s old comrades – who had also settled in the UK – died. One suspect, who had chosen Stan as best man for his wedding, killed himself.

Convinced of Stan’s guilt, John carried on investigating his stepfather. And then one day, while visiting Stan’s bungalow, in Telford, he managed to copy one of the War-time photos hidden under Stan’s bed.

Nick’s investigation is on BBC Sounds

Listen to: The Nazi Next Door

‘Do you know a war criminal?’

In March 1988, John saw a notice in a national newspaper.

It was asking for information about alleged criminals living in the UK who had been responsible for “genocide, murder or manslaughter in Germany or German-occupied territories” in World War Two.

The government had set up an inquiry after being given a list of suspects by Nazi investigators at the Simon Wiesenthal Center.

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher said at the time, according to security expert Prof Anthony Glees, failing to check the men’s backgrounds at the end of the War made the UK “look like a [Latin American] banana republic”.

John was convinced Stan was one of the men who had slipped through the net – not “just a guard” for Slonim’s local council, as he had claimed.

He wrote to the inquiry outlining the dreadful things Stan had told him. Letters passed back and forth. And police officers interviewed Stan. But John was told “no further action” would be taken because of a lack of evidence.

Stan now knew about John’s suspicions and had clearly been spooked by the police questioning. He applied for travel visas to Russia, Poland and Canada, where he had War-time friends and relatives.

And as wider police investigations continued, three of Stan’s old comrades – who had also settled in the UK – died. One suspect, who had chosen Stan as best man for his wedding, killed himself.

Convinced of Stan’s guilt, John carried on investigating his stepfather. And then one day, while visiting Stan’s bungalow, in Telford, he managed to copy one of the War-time photos hidden under Stan’s bed.

Nick’s investigation

is on BBC Sounds

Listen to: The Nazi Next Door

Slonim’s ‘death pits’

“We knew him as a butcher,” widow Alexandra Daletski said, looking at the photo of Stan, in 1996. “That is what he did – kill people.”

Having shared his suspicions with BBC News, John, and the then home-affairs correspondent Jon Silverman, were walking Slonim’s snowy streets, asking locals if they recognised the man in the photograph

In the image, Stan is wearing the uniform of the Belarusian Auxiliary Police – an armed civilian force of locals that carried out orders on behalf of the Nazis.

The date on the back of the original photo, according to John, was March 1942.

Ms Daletski said her husband, Jan, had been one of 200 people Stan and the local police had rounded up the same year. And she described how Stan – or Stasic, as he was known in Slonim – had shot Jan, after he had tried to run from the execution line.

Stan never disputed the Nazis had recruited him. But he always said it had not been until 1943 – after the bloody massacres of Slonim’s Jews – and even then only as a civilian guard.

He always denied being in the murderous auxiliary police.

But another witness, local church deacon Kazimir Adamovich, said he had watched from a farmer’s field as Stan shot 50 people over three days.

Killing had put Stan in a good mood, he said. He had found it as “easy as spitting”.

Their testimony suggested Stan had been present at the Slonim massacres – where tens of thousands of Jewish people and others were murdered. The mass killings began in autumn 1941, as Nazi Germany’s plan to exterminate Europe’s Jewish population stepped up a gear.

Men, women and children were marched into local forests, ordered to strip, and then shot. Their bodies fell on to the corpses of others already in the newly dug “death pits”.

John and the BBC News team also uncovered more evidence contradicting Stan’s original War-time story.

Stan, it seemed, had not escaped the Nazis to join Polish forces straight away.

Fleeing Slonim with the retreating Germans in June 1944 – as the Russians closed in – he was swept up with fellow collaborators and transported to eastern France to fight for a German Waffen-SS combat unit.

As the German defence crumbled, Stan became a prisoner of war. Only then, did he switch sides and join Polish forces.

Back in Telford, John and BBC News approached Stan. During the brief confrontation – after his weekly trip to church – Stan shouted denials and threatened to call the police.

It was the last time John and Stan spoke.

In light of the BBC News evidence, detectives re-interviewed Stan. But the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) again decided there was “insufficient evidence” for charges.

“I found it completely depressing,” John told me. “Scotland Yard had just pulled the shutters down.”

John drew a line under his investigation into Stan. His stepfather, he believed, had got away with murder.

And it was not until he met me – 20 years later – that he saw another chance to bring Stan to justice.

Ms Daletski said her husband, Jan, had been one of 200 people Stan and the local police had rounded up the same year. And she described how Stan – or Stasic, as he was known in Slonim – had shot Jan, after he had tried to run from the execution line.

Stan never disputed the Nazis had recruited him. But he always said it had not been until 1943 – after the bloody massacres of Slonim’s Jews – and even then only as a civilian guard. He always denied being in the murderous auxiliary police.

But another witness, local church deacon Kazimir Adamovich, said he had watched from a farmer’s field as Stan shot 50 people over three days.

Killing had put Stan in a good mood, he said. He had found it as “easy as spitting”.

Their testimony suggested Stan had been present at the Slonim massacres – where tens of thousands of Jewish people and others were murdered. The mass killings began in autumn 1941, as Nazi Germany’s plan to exterminate Europe’s Jewish population stepped up a gear.

Men, women and children were marched into local forests, ordered to strip, and then shot. Their bodies fell on to the corpses of others already in the newly dug “death pits”.

John and the BBC News team also uncovered more evidence contradicting Stan’s original War-time story.

Stan, it seemed, had not escaped the Nazis to join Polish forces straight away.

Fleeing Slonim with the retreating Germans in June 1944 – as the Russians closed in – he was swept up with fellow collaborators and transported to eastern France to fight for a German Waffen-SS combat unit.

As the German defence crumbled, Stan became a prisoner of war. Only then, did he switch sides and join Polish forces.

Back in Telford, John and BBC News approached Stan. During the brief confrontation – after his weekly trip to church – Stan shouted denials and threatened to call the police.

It was the last time John and Stan spoke.

In light of the BBC News evidence, detectives re-interviewed Stan. But the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) again decided there was “insufficient evidence” for charges.

“I found it completely depressing,” John told me. “Scotland Yard had just pulled the shutters down.”

John drew a line under his investigation into Stan. His stepfather, he believed, had got away with murder.

And it was not until he met me – 20 years later – that he saw another chance to bring Stan to justice.

The cold case

I work for BBC Radio Shropshire. And Stan, living in Telford, was in my patch.

Five years ago, I spotted several German news stories where elderly men had been tried for alleged Nazi war crimes committed more than 70 years before.

I remembered Stan’s story from the 1990s and contacted John. We got on well. And he was happy for me to begin my own investigation into Stan. By now, Stan was in his 90s and John his 70s.

I persuaded experienced Nazi investigator Dr Stephen Ankier to help me.

Stanislaw “Stan” Chrzanowski was one of hundreds of names reported to UK police after the 1988 appeal for war-crimes suspects. But in the end, only one man was convicted.

Retired British Rail ticket collector Anthony Sawoniuk was convicted in 1999 for murdering Jews. He died in prison, serving two life sentences.

Anthony Sawoniuk

Like Stan, Sawoniuk had been a member of the Belarusian Auxiliary Police, the German Waffen-SS and then Polish forces fighting with the Allies.

As many as 50,000 Nazi collaborators infiltrated Polish forces in the later stages of World War Two, historian Martin Dean, who worked on the government inquiry and for the Metropolitan Police’s War Crimes Unit, says.

About a third of them ended up in the UK.

“They would have had different degrees of involvement with the Nazis,” he says. “But some would be local policemen from places like Belarus.”

Through sources in Belarus, Dr Ankier obtained a document from Russia’s spy agency, the KGB, listing some of the War-time Belarusian Auxiliary Police officers in Slonim. And Stan’s name and date of birth was there – in black and white – proving he had lied about his real job in the War.

The list also helped us trace other suspects from Slonim to places in the UK. And it confirmed names of men Stan had mentioned to John over the years.

In total, more than 30 other suspected Nazi collaborators from Slonim settled in England and Wales after the War, Mr Dean says. But most are now believed dead.

Next, Nazi hunters at Germany’s specialist war crimes unit heard about our work and made contact.

On the strength of the Slonim witness testimonies gathered by John and BBC News in 1996, lead prosecutor Thomas Will told us he was prepared to look at mounting a case against Stan, using the evidence previously rejected by the CPS.

And Germany’s Federal Court of Justice ruled proceedings against Stan could continue – even though neither he nor his victims were German and his alleged crimes had been in Belarus.

“Because he was working for a German unit, it could be seen as a German crime,” Mr Will said.

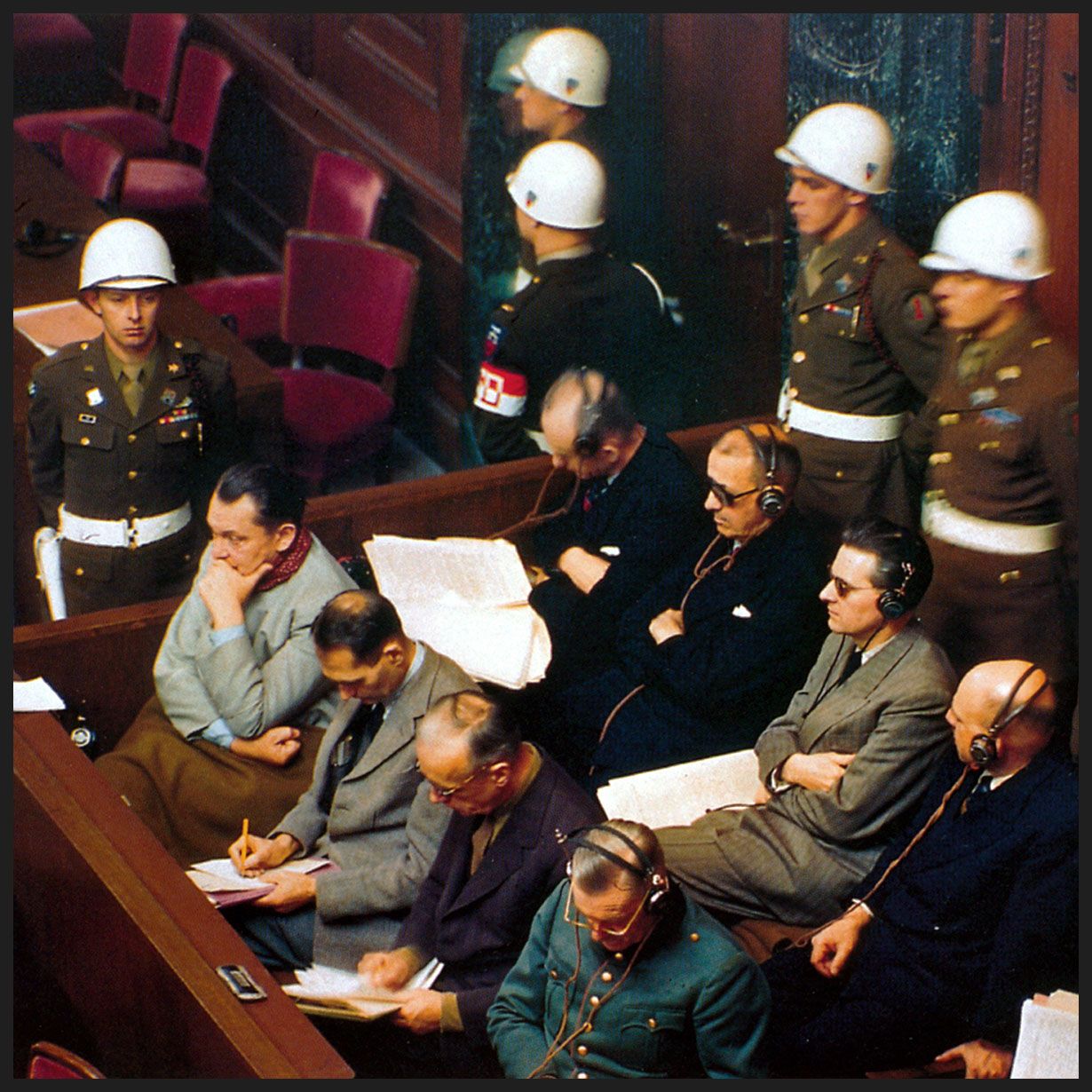

Investigators were pushing German law to its limit. They had legal powers far greater than the initial scope of the Nuremberg trials, after the War. And in a landmark case, Stan became the first UK citizen to be investigated by Germany for alleged war crimes.

Prosecutors centred on allegations he had murdered more than 30 civilians in Slonim, in winter 1942.

Hermann Goering, Rudolf Hess (front row left) and other Nuremberg defendants, 1945

But in October 2017 – as German police waited for the go-ahead to raid his home – Stan, 96, died.

Neighbours in Telford remember how he used to leave homegrown fruit on their doorsteps before setting off to the shops on his mobility scooter. Others talk of his fiery, unpredictable temper.

By now, Barbara had left Stan. She has since described him as a “brutal man” who threatened to kill her – but says she knew nothing about his abuse of John.

The German investigation provided relief for John. But less than six months later, he was taken ill and also died. He had kept his leukaemia diagnosis from me.

John Kingston

But it explained why, out of the blue, I had received a letter – just before his death – giving me permission to keep and use the evidence he had.

I wondered if I would find anything in the stash that might offer fresh insight into Stan and other Nazi collaborators.

And then – as I clambered around his attic – I found John’s cassette tapes labelled “war crimes”.

The cold case

I work for BBC Radio Shropshire. And Stan, living in Telford, was in my patch.

Five years ago, I spotted several German news stories where elderly men had been tried for alleged Nazi war crimes committed more than 70 years before.

I remembered Stan’s story from the 1990s and contacted John. We got on well. And he was happy for me to begin my own investigation into Stan. By now, Stan was in his 90s and John his 70s.

I persuaded experienced Nazi investigator Dr Stephen Ankier to help me.

Stanislaw “Stan” Chrzanowski was one of hundreds of names reported to UK police after the 1988 appeal for war-crimes suspects. But in the end, only one man was convicted.

Retired British Rail ticket collector Anthony Sawoniuk was convicted in 1999 for murdering Jews. He died in prison, serving two life sentences.

Anthony Sawoniuk

Like Stan, Sawoniuk had been a member of the Belarusian Auxiliary Police, the German Waffen-SS and then Polish forces fighting with the Allies.

As many as 50,000 Nazi collaborators infiltrated Polish forces in the later stages of World War Two, historian Martin Dean, who worked on the government inquiry and for the Metropolitan Police’s War Crimes Unit, says. About a third of them ended up in the UK.

“They would have had different degrees of involvement with the Nazis,” he says. “But some would be local policemen from places like Belarus.”

Through sources in Belarus, Dr Ankier obtained a document from Russia’s spy agency, the KGB, listing some of the War-time Belarusian Auxiliary Police officers in Slonim. And Stan’s name and date of birth was there – in black and white – proving he had lied about his real job in the War.

The list also helped us trace other suspects from Slonim to places in the UK. And it confirmed names of men Stan had mentioned to John over the years.

In total, more than 30 other suspected Nazi collaborators from Slonim settled in England and Wales after the War, Mr Dean says. But most are now believed dead.

Next, Nazi hunters at Germany’s specialist war crimes unit heard about our work and made contact.

On the strength of the Slonim witness testimonies gathered by John and BBC News in 1996, lead prosecutor Thomas Will told us he was prepared to look at mounting a case against Stan, using the evidence previously rejected by the CPS.

And Germany’s Federal Court of Justice ruled proceedings against Stan could continue – even though neither he nor his victims were German and his alleged crimes had been in Belarus.

“Because he was working for a German unit, it could be seen as a German crime,” Mr Will said. Investigators were pushing German law to its limit. They had legal powers far greater than the initial scope of the Nuremberg trials, after the War.

Hermann Goering, Rudolf Hess (front row left) and other Nuremberg defendants, 1945

And in a landmark case, Stan became the first UK citizen to be investigated by Germany for alleged war crimes. Prosecutors centred on allegations he had murdered more than 30 civilians in Slonim, in winter 1942.

But in October 2017 – as German police waited for the go-ahead to raid his home – Stan, 96, died.

Neighbours in Telford remember how he used to leave homegrown fruit on their doorsteps before setting off to the shops on his mobility scooter. Others talk of his fiery, unpredictable temper.

By now, Barbara had left Stan. She has since described him as a “brutal man” who threatened to kill her – but says she knew nothing about his abuse of John.

The German investigation provided relief for John. But less than six months later, he was taken ill and also died. He had kept his leukaemia diagnosis from me.

John Kingston

But it explained why, out of the blue, I had received a letter – just before his death – giving me permission to keep and use the evidence he had.

I wondered if I would find anything in the stash that might offer fresh insight into Stan and other Nazi collaborators.

And then – as I clambered around his attic – I found John’s cassette tapes labelled “war crimes”.

The tapes

John recorded his phone conversations with Stan for a few months in 1994 – to help a Sunday Express reporter expose him. When the article was published, police spoke to Stan again. But no action was taken.

According to John, Stan had given nothing away in the recordings. But when I listened, one section in particular caught my attention.

I heard Stan talk of an “English secret” he should not reveal.

His words – in broken English – were at times difficult to understand. But Stan appeared to be telling John the UK authorities had told him to stay silent.

“They, no… want this publicity,” he said.

“They waiting if we all dead, it is true.

“You take it, the secret, keep it with you all time – maybe even… to the dead.”

What was the secret? A short piece of newsreel footage – filmed a decade after the War – could provide the answer.

The tapes

John recorded his phone conversations with Stan for a few months in 1994 – to help a Sunday Express reporter expose him. When the article was published, police spoke to Stan again. But no action was taken.

According to John, Stan had given nothing away in the recordings. But when I listened, one section in particular caught my attention.

I heard Stan talk of an “English secret” he should not reveal.

His words – in broken English – were at times difficult to understand. But Stan appeared to be telling John the UK authorities had told him to stay silent.

“They, no… want this publicity,” he said.

“They waiting if we all dead, it is true.

“You take it, the secret, keep it with you all time – maybe even… to the dead.”

What was the secret? A short piece of newsreel footage – filmed a decade after the War – could provide the answer.

The face in the crowd

I watched hundreds of archive films to see if I could catch a glimpse of Stan in places we knew he had been.

It was a long shot – but I got lucky.

He showed up – not on World War Two footage – but in a batch of US newsreel material from March 1954, eight years after he arrived and settled in the UK.

The film shows Marienfelde transit camp, in West Berlin, where during the Cold War millions of people passed through from Communist East Berlin to capitalist West Berlin. The American narrator says the refugees are fleeing “red tyranny” in Eastern Europe.

And then suddenly there’s Stan, in an overcoat, walking into the arrivals hall. For a split-second, he looks straight down the camera lens.

To be sure it was him, I enlisted the help of a world-leading expert in facial mapping – Prof Hassan Ugail, from the University of Bradford. And he used specialist software to compare John’s old photographs of Stan with the man in the Berlin film.

“It’s definitely him,” he said.

Stan had told John he had never left the UK, after arriving in 1946. And Dr Ankier discovered – through a Freedom of Information request – Stan had said the same to police in 1961, when he applied for British citizenship.

Three photos of Stan

Remarkably, in a longer, unedited sequence of the film from the Marienfelde camp, we spotted four more men from photos in Stan’s collection.

Two had been photographed with Stan in Slonim during the German occupation, the others with him – in military uniforms – most likely when they fought for the Allies at the very end of the War.

The software looks for facial similarities. Anything above a 70% result is considered an accurate match. Stan – and the four others – all passed that bar.

For legal reasons, we cannot show the photos of the men with Stan or identify them in the film footage. But our investigations are continuing to try to confirm their names.

What were all five men – who had clearly met each other earlier in their lives – doing in Berlin during the Cold War?

The Marienfelde refugee camp itself may hold the key.

The face in the crowd

I watched hundreds of archive films to see if I could catch a glimpse of Stan in places we knew he had been.

It was a long shot – but I got lucky.

He showed up – not on World War Two footage – but in a batch of US newsreel material from March 1954, eight years after he arrived and settled in the UK.

The film shows Marienfelde transit camp, in West Berlin, where during the Cold War millions of people passed through from Communist East Berlin to capitalist West Berlin.

The American narrator says the refugees are fleeing “red tyranny” in Eastern Europe.

And then suddenly there’s Stan, in an overcoat, walking into the arrivals hall. For a split-second, he looks straight down the camera lens.

To be sure it was him, I enlisted the help of a world-leading expert in facial mapping – Prof Hassan Ugail, from the University of Bradford.

And he used specialist software to compare John’s old photographs of Stan with the man in the Berlin film.

“It’s definitely him,” he said.

Stan had told John he had never left the UK, after arriving in 1946. And Dr Ankier discovered – through a Freedom of Information request – Stan had said the same to police in 1961, when he applied for British citizenship.

Three photos of Stan

Remarkably, in a longer, unedited sequence of the film from the Marienfelde camp, we spotted four more men from photos in Stan’s collection.

Two had been photographed with Stan in Slonim during the German occupation, the others with him – in military uniforms – most likely when they fought for the Allies at the very end of the War.

The software looks for facial similarities. Anything above a 70% result is considered an accurate match. Stan – and the four others – all passed that bar.

For legal reasons, we cannot show the photos of the men with Stan or identify them in the film footage. But our investigations are continuing to try to confirm their names.

What were all five men – who had clearly met each other earlier in their lives – doing in Berlin during the Cold War?

The Marienfelde refugee camp itself may hold the key.

The complex was a sanctuary for people looking for a better life in the West – but it was also a hive of spies. Refugees from the East were useful sources of information.

“British, American and French intelligence wanted to learn as much as they could about Soviet forces and East Germany,” says Dr Keith Allen, from Germany’s Institute for Contemporary History.

When we presented our evidence on Stan to three security and intelligence experts, they all told us the evidence could point to him having spied for the UK.

Refugees at Marienfelde, July 1961

Stan’s language skills – he spoke Russian, Polish and German – would have been useful as the West tried to obtain details of the Soviets’ nuclear ambitions, author Steve Vogel says.

“US and British intelligence officers interviewed German scientists who had been taken to the Soviet Union to work.”

Stan had learned radio skills in the Polish army at the end of the War. And historian Dr Stephen Dorril says people like him were sent to Eastern Europe to set up intelligence networks.

“This is exactly what MI6 was doing - we know they trained people,” he says – stressing British security services would have known about Stan’s past with the Belarusian Auxiliary Police and German Waffen-SS.

“There has been a long-term cover-up,” he says. “Some of these people – their backgrounds were truly appalling.”

The complex was a sanctuary for people looking for a better life in the West – but it was also a hive of spies. Refugees from the East were useful sources of information.

“British, American and French intelligence wanted to learn as much as they could about Soviet forces and East Germany,” says Dr Keith Allen, from Germany’s Institute for Contemporary History.

When we presented our evidence on Stan to three security and intelligence experts, they all told us the evidence could point to him having spied for the UK.

Refugees at Marienfelde, July 1961

Stan’s language skills – he spoke Russian, Polish and German – would have been useful as the West tried to obtain details of the Soviets’ nuclear ambitions, author Steve Vogel says.

“US and British intelligence officers interviewed German scientists who had been taken to the Soviet Union to work.”

Stan had learned radio skills in the Polish army at the end of the War.

And historian Dr Stephen Dorril says people like him were sent to Eastern Europe to set up intelligence networks.

“This is exactly what MI6 was doing - we know they trained people,” he says – stressing British security services would have known about Stan’s past with the Belarusian Auxiliary Police and German Waffen-SS.

“There has been a long-term cover-up,” he says. “Some of these people – their backgrounds were truly appalling.”

Prof Anthony Glees, of the University of Buckingham, told us British security services had destroyed 110,000 files in the late 1980s and early 90s that “almost certainly included” details of any foreign-born Nazi collaborator who had gone on to work for UK intelligence.

We put this allegation to the government – but it did not respond.

The destruction of the documents was a “double-whammy cover-up”, Prof Glees says. Not only was any help given by collaborators to the UK authorities kept secret from the British public – but also any War-time crimes they had committed.

If they had been working undercover for the UK, Prof Glees says, Stan and others would have been protected from ever being tried for what they allegedly did in World War Two.

“The inducement would have been no prosecution – their passport to freedom.

“If you were a bad person [in the War] and feared what might happen to you, the more you offered [the intelligence services], the safer you were.”

Could this explain why there was only one war-crimes prosecution after the 1988 appeal for suspects?

Prof Glees, Dr Dorril and others are urging the UK government to follow the US secret service, the CIA, and release any remaining files connected to people such as Stan.

But not everyone we spoke to agreed Stan could have been a spy. Cold War historian and author Paul Maddrell told us he saw “no evidence of any connection between [Stan] and any intelligence agency”.

In a statement, the Home Office repeated what John had been told in the 1990s – the CPS had reviewed Stan’s case at the time but there had been insufficient evidence to proceed, with no real prospect of a conviction.

The Metropolitan Police also told us the case had failed to “meet the evidential test”.

Two photos of Stan as a young man

Senior figures in the Jewish community have described the updated evidence against Stan as “horrific and frightening”.

If he and others did work for British intelligence, then it is “a badge of shame for the UK” and a “double betrayal” of the War-time victims, the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s Efraim Zuroff – who sent the 1986 list of Nazi suspects to the Thatcher government – says.

“So many of these people should have – could have – been brought to justice,” he says. “It is sad one of the best democracies in the world could not get these people prosecuted.”

Board of Deputies of British Jews president Marie van der Zyl said it looked like a “huge cover-up” and is now calling for a public inquiry. Conservative MP Robert Halfon - who's Jewish - plans to call on the parliamentary security committee to investigate whether there were Nazi war criminals in the UK “who ended up working for British intelligence or any other organ of the state”.

Before he died, John told me he regretted so much of his life had been focused on his stepfather but was relieved his suspicions had been proved right.

And he recalled Stan’s arrogant boast – after being questioned by police in the 1990s – that he was able to convince people he was innocent.

“He said, ‘These people are buried in the ground [in Slonim],’” John said.

“‘They are buried and flattened.

“‘And here I am living my life.

“‘Whose side is God on?’

“I found that the most appalling thing I had ever heard.”

Prof Anthony Glees, of the University of Buckingham, told us British security services had destroyed 110,000 files in the late 1980s and early 90s that “almost certainly included” details of any foreign-born Nazi collaborator who had gone on to work for UK intelligence.

We put this allegation to the government – but it did not respond.

The destruction of the documents was a “double-whammy cover-up”, Prof Glees says. Not only was any help given by collaborators to the UK authorities kept secret from the British public – but also any War-time crimes they had committed.

If they had been working undercover for the UK, Prof Glees says, Stan and others would have been protected from ever being tried for what they allegedly did in World War Two.

“The inducement would have been no prosecution – their passport to freedom.

“If you were a bad person [in the War] and feared what might happen to you, the more you offered [the intelligence services], the safer you were.”

Could this explain why there was only one war-crimes prosecution after the 1988 appeal for suspects?

Prof Glees, Dr Dorril and others are urging the UK government to follow the US secret service, the CIA, and release any remaining files connected to people such as Stan.

But not everyone we spoke to agreed Stan could have been a spy. Cold War historian and author Paul Maddrell told us he saw “no evidence of any connection between [Stan] and any intelligence agency”.

In a statement, the Home Office repeated what John had been told in the 1990s – the CPS had reviewed Stan’s case at the time but there had been insufficient evidence to proceed, with no real prospect of a conviction.

The Metropolitan Police also told us the case had failed to “meet the evidential test”.

Two photos of Stan as a young man

Senior figures in the Jewish community have described the updated evidence against Stan as “horrific and frightening”.

If he and others did work for British intelligence, then it is “a badge of shame for the UK” and a “double betrayal” of the War-time victims, the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s Efraim Zuroff – who sent the 1986 list of Nazi suspects to the Thatcher government – says.

“So many of these people should have – could have – been brought to justice,” he says.

“It is sad one of the best democracies in the world could not get these people prosecuted.”

Board of Deputies of British Jews president Marie van der Zyl said it looked like a “huge cover-up” and is now calling for a public inquiry. Conservative MP Robert Halfon - who's Jewish - plans to call on the parliamentary security committee to investigate whether there were Nazi war criminals in the UK “who ended up working for British intelligence or any other organ of the state”.

Before he died, John told me he regretted so much of his life had been focused on his stepfather but was relieved his suspicions had been proved right.

And he recalled Stan’s arrogant boast – after being questioned by police in the 1990s – that he was able to convince people he was innocent.

“He said, ‘These people are buried in the ground [in Slonim],’” John said.

“‘They are buried and flattened.

“‘And here I am living my life.

“‘Whose side is God on?’

“I found that the most appalling thing I had ever heard.”

Slonim’s Jews before the massacres

Slonim’s Jews before the massacres

Credits

Author: Nick Southall

Special thanks to Nazi investigator Dr Stephen Ankier, audio specialist Ed Primeau and Prof Hassan Ugail from the University of Bradford

Top artwork of Stan as a prisoner of war by Louise Cobbold

Graphic maps: Salim Qurashi

Images: John Kingston, BBC, Getty Images, Yad Vashem

Editors: Paul Kerley and Dave Green

Long Reads editor: Kathryn Westcott

You may also like

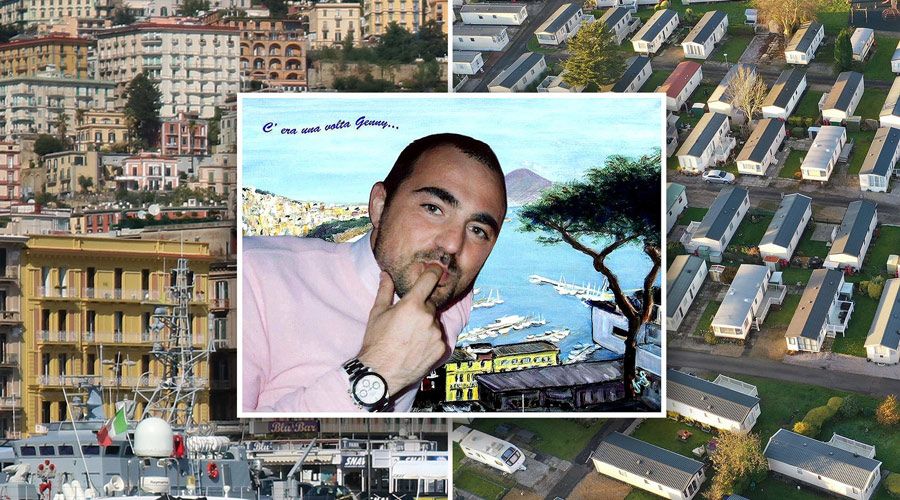

The Lancashire hideaway of an Italian mafia boss

The suspected gangster at the heart of world boxing

Credits

Author: Nick Southall

Special thanks to Nazi investigator Dr Stephen Ankier, audio specialist Ed Primeau and Prof Hassan Ugail from the University of Bradford

Top artwork of Stan as a prisoner of war by Louise Cobbold

Graphic maps: Salim Qurashi

Other images: John Kingston, BBC, Getty Images, Yad Vashem

Editors: Paul Kerley and Dave Green

Long Reads editor: Kathryn Westcott

You may also like

The Lancashire hideaway of an Italian mafia boss

The suspected gangster at the heart of world boxing