The wheelchair warriors

Their rebellious protests to change the law

The wheelchair warriors

Their rebellious protests to change the law

By Damon Rose

A train pulls into Cardiff Queen Street Station on a bright spring morning and the carriage doors slide open.

Quickly, a young man in a black beanie hat launches himself out of his wheelchair from the platform onto the train carriage floor. To the surprise of the passengers, he handcuffs himself to a handrail.

Further along the platform, others have done the same.

The man in the hat is pulled from the train by two police officers who struggle to keep hold of him. He twists and turns, managing to break free for a few seconds in a vain attempt to get back on board.

The train’s going nowhere. That’s what this small group of protesters want. By disrupting the service, they’re hoping to highlight something they come up against daily - the difficulties of accessing public transport.

One officer tells a young demonstrator she’s causing an obstruction to the train. But the woman tells him from her wheelchair that the station itself is the obstruction. “I couldn’t access Platform 3,” she says.

The woman is initially arrested, but then let off with a warning. It’s difficult for the police to put people in wheelchairs in their inaccessible vans - and that’s why, she reckons, she’s been “de-arrested”.

This dramatic protest - in spring 1995 - was just one of many staged on buses and trains across the UK in the fight for disabled civil rights.

Back then, it was not illegal to discriminate against disabled people in many areas of everyday life.

By Damon Rose

A train pulls into Cardiff Queen Street Station on a bright spring morning and the carriage doors slide open. Quickly, a young man in a black beanie hat launches himself out of his wheelchair from the platform onto the train carriage floor.

To the surprise of the passengers, he handcuffs himself to a handrail.

Further along the platform, others have done the same.

The man in the hat is pulled from the train by two police officers who struggle to keep hold of him. He twists and turns, managing to break free for a few seconds in a vain attempt to get back on board.

The train’s going nowhere. That’s what this small group of protesters want. By disrupting the service, they’re hoping to highlight something they come up against daily - the difficulties of accessing public transport.

One officer tells a young demonstrator she’s causing an obstruction to the train. But the woman tells him from her wheelchair that the station itself is the obstruction. “I couldn’t access Platform 3,” she says.

The woman is initially arrested, but then let off with a warning. It’s difficult for the police to put people in wheelchairs in their inaccessible vans - and that’s why, she reckons, she’s been “de-arrested”.

This dramatic protest - in spring 1995 - was just one of many staged on buses and trains across the UK in the fight for disabled civil rights.

Back then, it was not illegal to discriminate against disabled people in many areas of everyday life.

Barbara Lisicki felt angry and ignored.

“There was no sense of outrage anywhere until we started really pushing it,” she says. “Disabled people were so clearly socially excluded.”

In the early 1970s, Barbara was living in north London with her mum and brothers. As a young child, she was “non-disabled”.

She couldn’t get on with the rules at her “posh and very strict school” and her sense of personal justice was already being tested.

“I got expelled. It was a convent run by nuns. I was rejecting the mindless discipline and religious zealotry.

“I built up so many detentions there wasn’t enough time in the year for me to do them all.”

Barbara Lisicki with her former partner and fellow campaigner Alan Holdsworth

Soon afterwards, Barbara developed a high temperature which wouldn’t go away - it was an early sign that her life was going to change.

Eventually, she ended up at a specialist juvenile rheumatology hospital in Taplow, Buckinghamshire. She remained there for over a year.

Barbara tells me she was diagnosed with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis which causes pain, swelling and stiffness in her joints. It’s an autoimmune condition usually affecting the hands, feet and wrists. As Barbara puts it: “It’s basically where your body starts attacking itself.”

She made some friends at Taplow, but describes the overall experience as “horrible and oppressive”.

Once again, she found herself breaking the rules - regularly escaping the ward with an older girl.

In the hospital, they were made to use wheelchairs so as not to put too much weight on their hips.

“But we used to dump the wheelchairs in the bushes and hitchhike to the pub,” says Barbara. “They’d be sending out search parties and we’d be down there having a vodka and lime. I was 16.”

Barbara Lisicki

Barbara acknowledges she was smart, well-read and “a player”. She got a degree at university and a postgraduate teaching qualification.

“I thought: ‘I’m not going to be able to do a manual or factory job. Basically, I’m going to have to do something where I can sit down a lot!’”

But she struggled to get a teaching job.

That’s when her “get it” moment happened. She realised that employers were unwilling to offer a job to a disabled person. Many disabled people have “get it” moments, including me.

I'm blind, and when I was in my early 20s a security guard tried to stop me taking my guide dog into a cinema. Other staff helped me, but for the whole film I was worried I’d be made to leave, when I hadn’t done anything wrong.

Barbara says her opportunities were blocked by discrimination.

“I put down [on application forms] I had a long-term condition - I’m not even sure I used the term disabled person. I simply wasn’t getting jobs.”

“Everybody I qualified with on the teaching course got taken on except me. I’d done better than many of them - achieving credits and distinctions.

“It just struck me then, it was because I had an impairment. I was a disabled person.”

Barbara Lisicki felt angry and ignored.

“There was no sense of outrage anywhere until we started really pushing it,” she says. “Disabled people were so clearly socially excluded.”

In the early 1970s, Barbara was living in north London with her mum and brothers. As a young child, she was “non-disabled”.

She couldn’t get on with the rules at her “posh and very strict school” and her sense of personal justice was already being tested.

“I got expelled. It was a convent run by nuns. I was rejecting the mindless discipline and religious zealotry.

“I built up so many detentions there wasn’t enough time in the year for me to do them all.”

Barbara Lisicki with her former partner and fellow campaigner Alan Holdsworth

Soon afterwards, Barbara developed a high temperature which wouldn’t go away - it was an early sign that her life was going to change.

Eventually, she ended up at a specialist juvenile rheumatology hospital in Taplow, Buckinghamshire. She remained there for over a year.

Barbara tells me she was diagnosed with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis which causes pain, swelling and stiffness in her joints. It’s an autoimmune condition usually affecting the hands, feet and wrists. As Barbara puts it: “It’s basically where your body starts attacking itself.”

She made some friends at Taplow, but describes the overall experience as “horrible and oppressive”.

Once again, she found herself breaking the rules - regularly escaping the ward with an older girl.

In the hospital, they were made to use wheelchairs so as not to put too much weight on their hips.

“But we used to dump the wheelchairs in the bushes and hitchhike to the pub,” says Barbara. “They’d be sending out search parties and we’d be down there having a vodka and lime. I was 16.”

Barbara Lisicki

Barbara acknowledges she was smart, well-read and “a player”. She got a degree at university and a postgraduate teaching qualification.

“I thought: ‘I’m not going to be able to do a manual or factory job. Basically, I’m going to have to do something where I can sit down a lot!’”

But she struggled to get a teaching job.

That’s when her “get it” moment happened. She realised that employers were unwilling to offer a job to a disabled person. Many disabled people have “get it” moments, including me.

I'm blind, and when I was in my early 20s a security guard tried to stop me taking my guide dog into a cinema. Other staff helped me, but for the whole film I was worried I’d be made to leave, when I hadn’t done anything wrong.

Barbara says her opportunities were blocked by discrimination.

“I put down [on application forms] I had a long-term condition - I’m not even sure I used the term disabled person. I simply wasn’t getting jobs.”

“Everybody I qualified with on the teaching course got taken on except me. I’d done better than many of them - achieving credits and distinctions.

“It just struck me then, it was because I had an impairment. I was a disabled person.”

Sue Elsegood was, like Barbara, part of a network of demonstrators determined to bring about change. She was the young woman arrested - and then de-arrested - at Cardiff Queen Street Station.

For her, it started in 1990 when she got a call from a friend asking if she fancied hijacking a bus.

Back then, few buses were accessible and wheelchair users had to give several days’ notice to travel by train. Even then, they were put in the guard’s van because of lack of space in the carriages.

She found herself in central London on a direct action protest run by CAT, the Campaign for Accessible Transport.

They knew their wheelchairs meant they couldn’t actually get on a bus, but they could block traffic on Oxford Street.

“I realised then that buses should be for everyone, including us. Up to that point, I just thought it was my fault I couldn’t walk and couldn’t get on,” she says.

“It’s actually possible to invent a ramp or a lift for the bus, whereas for me to be medically-cured was not within the realms of possibility at that time.”

Sue and 14 others were arrested, but charges against them were later dropped. She’s convinced it’s because the magistrates’ courts weren’t accessible.

Sue Elsegood at a 1990s bus protest (above) and more recently (below)

Disabled people then, as now, didn’t want to be seen as charity cases.

In 1989, Barbara Lisicki went on television to say so.

She didn’t accept the negative portrayals, as she saw it, of disabled people on shows like Children in Need.

“If you make a disabled person an object of charity, you’re not going to see them as your equal,” she told BBC executives on the discussion programme, Network.

“It isn’t just about individuals giving money. It isn’t just about having mass appeals on television. It’s about having rights. I want people to realise that disabled people have no rights.”

ITV was not spared. In 1988, it started its own charity extravaganza. Telethon was on air for 27 hours non-stop over the late May Bank Holiday.

The main studio was filled with a cheering audience, giant cheques were waved in the air, and an array of famous faces performed for the cameras.

Alan Holdsworth

Alan Holdsworth, Barbara’s partner during the 1990s and fellow campaigner, got a phone call from a youth worker asking if he’d seen the negative way disabled people, she felt, were shown on screen.

“She told me her young people were really pissed off with it. Was there anything we could do?”

Alan, Barbara and friends were often asked to protest - they were known for their ability to organise. But Telethon was different.

“It was the easiest action ever to organise,” says Alan who staged demos in both 1990 and 1992.

“I couldn’t believe how many people hated it. I’d never watched it. I don’t want to watch that kind of thing, the images were just so pathetic.”

Sue Elsegood was, like Barbara, part of a network of demonstrators determined to bring about change. She was the young woman arrested - and then de-arrested - at Cardiff Queen Street Station.

For her, it started in 1990 when she got a call from a friend asking if she fancied hijacking a bus.

Back then, few buses were accessible and wheelchair users had to give several days’ notice to travel by train. Even then, they were put in the guard’s van because of lack of space in the carriages.

She found herself in central London on a direct action protest run by CAT, the Campaign for Accessible Transport.

They knew their wheelchairs meant they couldn’t actually get on a bus, but they could block traffic on Oxford Street.

“I realised then that buses should be for everyone, including us. Up to that point, I just thought it was my fault I couldn’t walk and couldn’t get on,” she says.

“It’s actually possible to invent a ramp or a lift for the bus, whereas for me to be medically-cured was not within the realms of possibility at that time.”

Sue and 14 others were arrested, but charges against them were later dropped. She’s convinced it’s because the magistrates’ courts weren’t accessible.

Sue Elsegood at a 1990s bus protest (above) and more recently (below)

Disabled people then, as now, didn’t want to be seen as charity cases.

In 1989, Barbara Lisicki went on television to say so.

She didn’t accept the negative portrayals, as she saw it, of disabled people on shows like Children in Need.

“If you make a disabled person an object of charity, you’re not going to see them as your equal,” she told BBC executives on the discussion programme, Network.

“It isn’t just about individuals giving money. It isn’t just about having mass appeals on television. It’s about having rights. I want people to realise that disabled people have no rights.”

ITV was not spared. In 1988, it started its own charity extravaganza. Telethon was on air for 27 hours non-stop over the late May Bank Holiday.

The main studio was filled with a cheering audience, giant cheques were waved in the air, and an array of famous faces performed for the cameras.

Alan Holdsworth

Alan Holdsworth, Barbara’s partner during the 1990s and fellow campaigner, got a phone call from a youth worker asking if he’d seen the negative way disabled people, she felt, were shown on screen.

“She told me her young people were really pissed off with it. Was there anything we could do?”

Alan, Barbara and friends were often asked to protest - they were known for their ability to organise. But Telethon was different.

“It was the easiest action ever to organise,” says Alan who staged demos in both 1990 and 1992.

“I couldn’t believe how many people hated it. I’d never watched it. I don’t want to watch that kind of thing, the images were just so pathetic.”

One particular slogan the police singled out on placards in 1990 was “Piss on Pity”.

“[It was] the one sign they said they’d arrest me for, if I didn’t take it down’,” says Alan - even though the bad language on other signs was much worse.

But the provocative slogan stuck. And Piss on Pity T-shirts began to make appearances at later demos - after all, it would be more difficult for police to insist on them being removed.

“I’ve now sold about 20,000 of them,” says Alan.

At the 1992 Telethon, Alan and Barbara staged “Block Telethon” - a demonstration and street-party with speeches, songs and comedy - outside ITV’s studios on London’s South Bank. Over 1,000 activists blocked the road making it difficult for celebrities’ cars to get into the building.

ITV’s 1992 Telethon was to be the last.

More from BBC News:

Was 1995 the year that changed everything for disabled people?

Frank Gardner on the ‘iceberg’ of disability

“Barbara and Alan were dynamic and engaging personalities. People were drawn to them to hear about these exciting protests - where we’d be chaining ourselves to buses and getting arrested,” says Sue Elsegood.

“They both had a political vision as to how we could challenge structural inequalities - and the demonstrations were powerful and quite sexy really.”

In 1993, Sue, Barbara and Alan helped form a new group, the Disabled People’s Direct Action Network - or DAN.

Over the next few years, DAN would stage many dramatic, non-violent protests across the UK.

Barbara and Alan also used their alter egos - sharp-tongued comedian Wanda Barbara and singer-songwriter Johnny Crescendo - to drum up support at “Tragic But Brave” roadshow events and “Workhouse” cabarets.

“We went around disability organisations performing and telling jokes,” says Alan. “We then talked to them in the bar afterwards to see what they wanted to do.”

“The comedy and music was all about our experiences as disabled people. It was politicising us,” says Sue.

One particular slogan the police singled out on placards in 1990 was “Piss on Pity”.

“[It was] the one sign they said they’d arrest me for, if I didn’t take it down’,” says Alan - even though the bad language on other signs was much worse.

But the provocative slogan stuck. And Piss on Pity T-shirts began to make appearances at later demos - after all, it would be more difficult for police to insist on them being removed.

“I’ve now sold about 20,000 of them,” says Alan.

At the 1992 Telethon, Alan and Barbara staged “Block Telethon” - a demonstration and street-party with speeches, songs and comedy - outside ITV’s studios on London’s South Bank. Over 1,000 activists blocked the road making it difficult for celebrities’ cars to get into the building.

ITV’s 1992 Telethon was to be the last.

More from BBC News:

Was 1995 the year that changed everything for disabled people?

Frank Gardner on the ‘iceberg’ of disability

“Barbara and Alan were dynamic and engaging personalities. People were drawn to them to hear about these exciting protests - where we’d be chaining ourselves to buses and getting arrested,” says Sue Elsegood.

“They both had a political vision as to how we could challenge structural inequalities - and the demonstrations were powerful and quite sexy really.”

In 1993, Sue, Barbara and Alan helped form a new group, the Disabled People’s Direct Action Network - or DAN.

Over the next few years, DAN would stage many dramatic, non-violent protests across the UK.

Barbara and Alan also used their alter egos - sharp-tongued comedian Wanda Barbara and singer-songwriter Johnny Crescendo - to drum up support at “Tragic But Brave” roadshow events and “Workhouse” cabarets.

“We went around disability organisations performing and telling jokes,” says Alan. “We then talked to them in the bar afterwards to see what they wanted to do.”

“The comedy and music was all about our experiences as disabled people. It was politicising us,” says Sue.

DAN’s first high-profile national action took place in Christchurch, Dorset.

A by-election was to be held in the safe Conservative seat, after the death of MP Robert Adley.

The Tory candidate, Rob Hayward, had already been an MP - but had lost his seat at the 1992 general election.

In parliament, he’d upset campaigners when he “talked out” (deliberately wasted time) a reading of a disabled civil rights bill put forward by a Labour MP. It meant the bill couldn’t become law. A week later he apologised to MPs.

DAN protesters in Christchurch

Enraged, DAN members spent a day chasing him in their wheelchairs around Christchurch during his campaign.

The tide was already turning against John Major’s Conservative government, but Alan Holdsworth believes DAN played a part in Rob Hayward’s defeat.

The Liberal Democrats took Christchurch.

DAN’s first high-profile national action took place in Christchurch, Dorset.

A by-election was to be held in the safe Conservative seat, after the death of MP Robert Adley.

The Tory candidate, Rob Hayward, had already been an MP - but had lost his seat at the 1992 general election.

In parliament, he’d upset campaigners when he “talked out” (deliberately wasted time) a reading of a disabled civil rights bill put forward by a Labour MP. It meant the bill couldn’t become law. A week later he apologised to MPs.

DAN protesters in Christchurch

Enraged, DAN members spent a day chasing him in their wheelchairs around Christchurch during his campaign.

The tide was already turning against John Major’s Conservative government, but Alan Holdsworth believes DAN played a part in Rob Hayward’s defeat.

The Liberal Democrats took Christchurch.

But it was the resourceful and unruly way DAN members approached public transport that really caught attention.

Wheelchairs blocked main roads and DAN members either handcuffed themselves to buses - or pulled themselves underneath vehicles - to prevent them from moving.

In February 1995, they brought traffic on Westminster Bridge in central London to a standstill.

Barbara argued with a furious bus driver, Sue was carried away in her wheelchair by police, while Alan handcuffed himself to a double-decker.

And the chants were infectious.

They call us wheelchair warriors, we’re kicking up some fuss

And we will keep on marching ‘til you let us on the bus

At the Cardiff station protest - where Sue was let off by police - Alan was actually arrested and charged with obstructing a train.

Barbara recalls how she and a friend were arrested at a London bus protest and taken to a police station with accessible cells.

“They didn’t search us. We must’ve looked too innocent,” she says. “We had a camera with us and took photos in our cell.”

From 1982 to the mid-1990s there were 14 failed attempts to get civil rights legislation for disabled people through parliament.

But thanks to both DAN’s direct action protests - and more traditional campaigning from Rights Now, a wider alliance of disability groups - the time for change was approaching.

But it was the resourceful and unruly way DAN members approached public transport that really caught attention.

Wheelchairs blocked main roads and DAN members either handcuffed themselves to buses - or pulled themselves underneath vehicles - to prevent them from moving.

In February 1995, they brought traffic on Westminster Bridge in central London to a standstill.

Barbara argued with a furious bus driver, Sue was carried away in her wheelchair by police, while Alan handcuffed himself to a double-decker.

And the chants were infectious.

They call us wheelchair warriors, we’re kicking up some fuss

And we will keep on marching ‘til you let us on the bus

At the Cardiff station protest - where Sue was let off by police - Alan was actually arrested and charged with obstructing a train.

Barbara recalls how she and a friend were arrested at a London bus protest and taken to a police station with accessible cells.

“They didn’t search us. We must’ve looked too innocent,” she says. “We had a camera with us and took photos in our cell.”

From 1982 to the mid-1990s there were 14 failed attempts to get civil rights legislation for disabled people through parliament.

But thanks to both DAN’s direct action protests - and more traditional campaigning from Rights Now, a wider alliance of disability groups - the time for change was approaching.

Disabled people hoped for the same legal protection offered to ethnic minorities under the Race Relations Act, and women under the Sex Discrimination Act.

In 1994, the Minister for Disabled People, Sir Nicholas Scott, had to apologise for misleading MPs over the government’s undercover attempts to kill a Labour private members bill, which would have given disabled people equal rights.

Two months’ later he was replaced in the job by William Hague, who helped draft a new bill - a political compromise between government and parliament - that stood a better chance of becoming law.

The Disability Discrimination Act, or DDA, passed on 8 November 1995.

“An Act to make it unlawful to discriminate against disabled persons in connection with employment, the provision of goods, facilities and services or the disposal or management of premises; to make provision about the employment of disabled persons; and to establish a National Disability Council.”

But still campaigners felt it didn’t go far enough.

Unlike the race and sex discrimination acts, there was no body with legal powers to make sure the new rules were being enforced. The Disability Rights Commission wasn’t established until 1999.

Barbara Lisicki describes the National Disability Council set up instead as an “ineffective compromise body”.

Some measures outlined in the DDA, including the “reasonable adjustments” service providers had to make so disabled people had access, didn’t have to be in place for nearly a decade.

And what about being able to get on and off buses and trains more easily? That would need more legislation and more years of waiting.

Barbara is both critical and pragmatic about the DDA.

“We accepted we had some level of victory because legislation had finally been passed. But we were all aware it was weak and wasn’t going to do what was needed.”

DAN’s work was not finished. There were more protests.

Disabled people hoped for the same legal protection offered to ethnic minorities under the Race Relations Act, and women under the Sex Discrimination Act.

In 1994, the Minister for Disabled People, Sir Nicholas Scott, had to apologise for misleading MPs over the government’s undercover attempts to kill a Labour private members bill, which would have given disabled people equal rights.

Two months’ later he was replaced in the job by William Hague, who helped draft a new bill - a political compromise between government and parliament - that stood a better chance of becoming law.

The Disability Discrimination Act, or DDA, passed on 8 November 1995.

“An Act to make it unlawful to discriminate against disabled persons in connection with employment, the provision of goods, facilities and services or the disposal or management of premises; to make provision about the employment of disabled persons; and to establish a National Disability Council.”

But still campaigners felt it didn’t go far enough.

Unlike the race and sex discrimination acts, there was no body with legal powers to make sure the new rules were being enforced. The Disability Rights Commission wasn’t established until 1999.

Barbara Lisicki describes the National Disability Council set up instead as an “ineffective compromise body”.

Some measures outlined in the DDA, including the “reasonable adjustments” service providers had to make so disabled people had access, didn’t have to be in place for nearly a decade.

And what about being able to get on and off buses and trains more easily? That would need more legislation and more years of waiting.

Barbara is both critical and pragmatic about the DDA.

“We accepted we had some level of victory because legislation had finally been passed. But we were all aware it was weak and wasn’t going to do what was needed.”

DAN’s work was not finished. There were more protests.

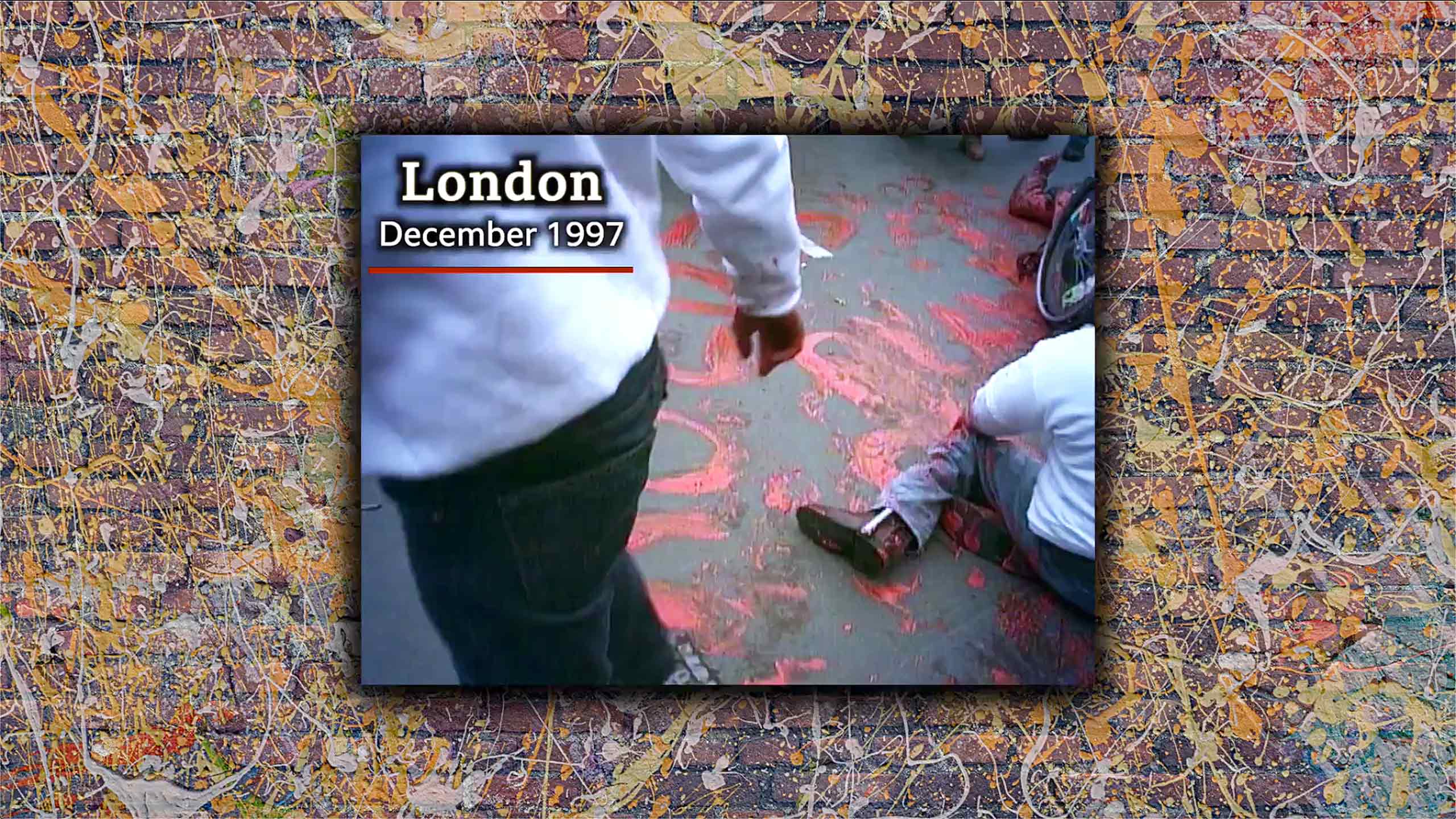

“We had some red water-based paint,” says Sue Elsegood.

It was late 1997, a few months after Tony Blair had moved into Number 10, and DAN heard that Labour wanted to reduce the welfare budget. They rolled up at the gates of Downing Street.

“We took the paint in takeaway food containers, so it looked like we’d taken our lunch with us as tourists. We threw it, spelling out the words ‘Blair’s blood’.

“The cuts were going to make us bleed, make us suffer, as disabled people. We knew there were lots of people who wouldn’t be able to afford their heating with the benefit cuts he was proposing.”

Sue remembers how one activist had a seizure during the protest.

“He fell out of his chair and got covered in paint. The police didn’t know what to do. They went in to arrest us all but didn’t want to get red paint on their uniforms.

“It wasn’t permanent damage, we were non-violent. We were out to get a message across and to reverse Blair’s policy. And we did, he didn’t go ahead with it at that time.”

Podcast: Ouch - where real disability talk happens

It’s a quarter of a century since the Disability Discrimination Act gave disabled people a legal starting point in the struggle for full civil rights.

The positive thing that most people agree on is that it acknowledged in law, for the first time, that disabled people were discriminated against.

Ten years ago, the DDA and more than 100 other separate pieces of legislation in England, Wales and Scotland, were rolled together into one piece of law, the Equality Act 2010.

DAN has been disbanded but, since the March lockdown, some old members have been meeting up on Zoom - a chance to reminisce.

“When you were chained to a train or bus, you had to rely on other members to keep you safe. You didn’t want the driver heading off with you still attached,” says Sue.

“There’s still that really strong bond between us. It’s because we had to trust each other with our lives.”

Credits

Author: Damon Rose

Editor/Producer: Paul Kerley

Long reads editor: Kathryn Westcott

Photography: Getty Images, PA Media, Shutterstock and Emma Lynch

Additional images: Sue Elsegood, David Hevey (Wanda Barbara poster), Alan Holdsworth (aka Johnny Crescendo), Barbara Lisicki, Dave Lupton (Crippen cartoons)

Video: BBC News and BBC Disability Programmes Unit/Rave Productions

Thanks to Alex Cowan at the National Disability Arts Collection and Archive

More Long Reads

How the falling boys were saved

The story of the Mangrove Nine