The five boys who

didn’t come home

The story of the 1971 Ibrox Disaster

Eight teenage boys hurry along a quiet Fife road talking excitedly about their day ahead. It is two days after the Hogmanay celebrations that mark new year in Scotland.

The skies above are leaden grey for the two-mile walk from their home village of Markinch to the town of Glenrothes. There, supporters’ buses will ferry them to Glasgow for the biggest match in the Scottish football calendar - Rangers versus Celtic.

The group are tight - their homes are just yards from each other - so the only real division is the colour of their teams. For three it’s the green of Celtic, for the other five the blue of Rangers.

As they file on to the separate buses, there’s a few friendly shouts and waves before the coaches pull away. Eight school friends, the youngest just 13 years old, making the journey to watch a football match.

Only three will come home.

Warning: Contains descriptions and images some readers may find upsetting.

The Ibrox Stadium crush on 2 January 1971 was one of the worst peacetime disasters in Scotland. It left 66 people dead and more than 140 injured.

It laid bare football’s often lax attitude to the safety of its supporters, years before the painful lessons of the tragedies at Bradford and Hillsborough.

Fifty years on, the horror of Stairway 13 still touches those who were there and survived and the families of those who were lost.

Glasgow’s big match

In 1971 Glasgow was a city in flux. The ill winds of the UK’s decline as a manufacturing giant were being keenly felt on the banks of the Clyde. But just as the city’s shipbuilding industry looked under threat, other parts of the fabric of traditional life were still thriving.

Less than a 20-minute walk from where giant shipyard cranes dominated the sky above the Govan area of Glasgow was Ibrox Stadium, home to Rangers Football Club.

The ground was typical of the era with steep terraces that swept round to a red brick grandstand with the motif criss-cross balcony of acclaimed stadium architect Archibald Leitch.

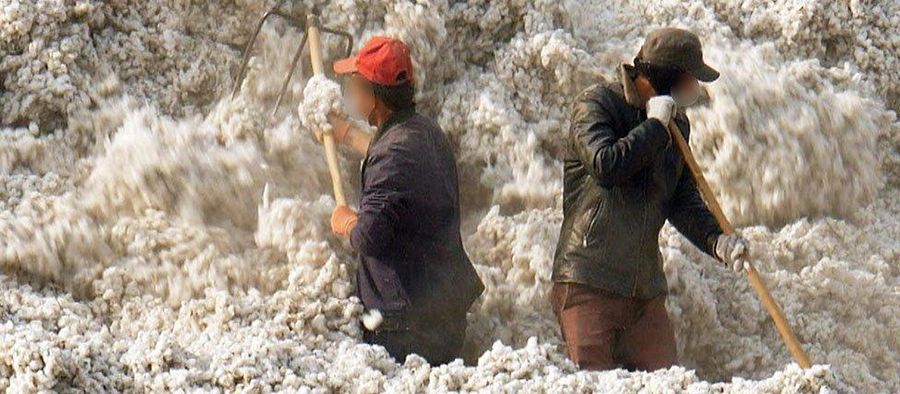

(Top row) Rangers fans Bryan Todd, Ronald Paton, Peter Easton, Mason Philip. (Bottom row) Rangers fan Douglas Morrison and the Celtic boys Joe Mitchell, Peter Lee and Shane Fenton.

Ibrox had once held nearly 120,000 fans, but on 2 January 1971 the capacity was capped at 80,000 for the visit of Rangers’ oldest rivals.

The Markinch boys supporting Celtic - Shane Fenton, Peter Lee and Joe Mitchell - made their way to the west end of the stadium to join the fans. The other five - Bryan Todd, Ronald Paton, Peter Easton, Mason Philip and Douglas Morrison - went to the opposite Rangers end, behind the goal.

One of the most celebrated football derbies on the planet, this particular ‘Old Firm’ game was a muted affair for the first 89 minutes, matching the gloom of the freezing mist that crept into Glasgow that day.

Celtic take the lead as the seconds tick down to the final whistle.

But Rangers score in the 90th minute for a 1-1 finish.

“The game itself was pretty unspectacular,” remembers Peter. “Celtic scored the goal and we decided to leave so we would miss the big crowd because there was always a lot of congestion coming out of the game.

“We didn’t realise until some of the older guys came back onto the bus that Rangers had actually equalised in the last minute.”

After an explosive finish to a drab game, referee Willie Anderson blew his whistle for full time at 4.41pm. Matchday announcer Kenneth McFarlane signed off with a reminder that, “spectators are requested to exercise care in leaving the stadium”.

Just minutes later hundreds of football fans would be trapped in one of the worst crushes ever witnessed at a British sports ground.

80,000 supporters filled Glasgow’s Ibrox Stadium

A river bursting its banks

Attending football matches in 1971 had barely changed from the game’s flat-capped boom years in the early part of the 20th Century. Being swept along by a huge tide of humanity was part of the ritual at big games like the Old Firm clash.

Douglas, Peter, Ronald, Mason and Bryan joined the throng of Rangers fans shuffling towards the exit closest to the Govan streets where the supporters’ buses were parked. They were heading to Stairway 13.

Even by the standards at the time, Stairway 13 was not for the faint-hearted with between 18,000 and 25,000 spectators using its steeply raked steps to leave the match. Corralled into seven lanes divided by tubular steel rails, the exit was packed as usual but those in its grip that day knew this was different.

One of the main stairways at Ibrox on a less crowded match day.

One of the main stairways at Ibrox on a less crowded match day.

The first sign of any trouble was white handkerchiefs being waved in the air - a common occurrence on the packed terraces in those days when first aiders were needed. Then came the whistles, the shouts and pleas for those at the top of Stairway 13 to move back.

But it was all in vain, a vice-like pressure was building as more and more fans joined the top of the stairway from the terraces. The epicentre of the crush was between the first and third landings in the first two lanes of the stairway.

Nobody there could move but more people kept coming. The barriers buckled... and then collapsed.

One onlooker in the tenement flat opposite described the scene as like a “river bursting its banks”, another “like a pack of cards that had been thrown forward; the lower ones were horizontal, others were semi-upright and the last were upright.”

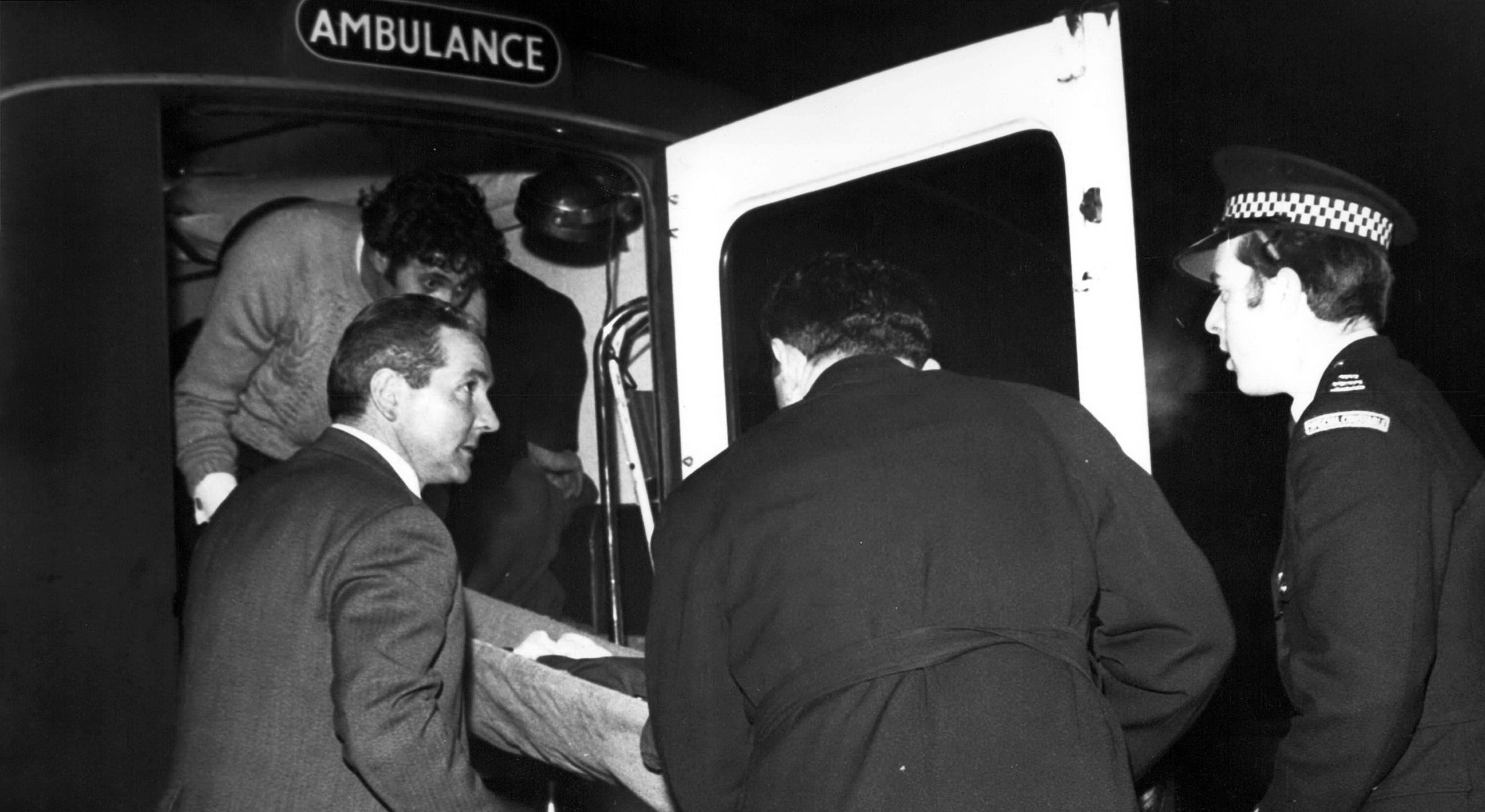

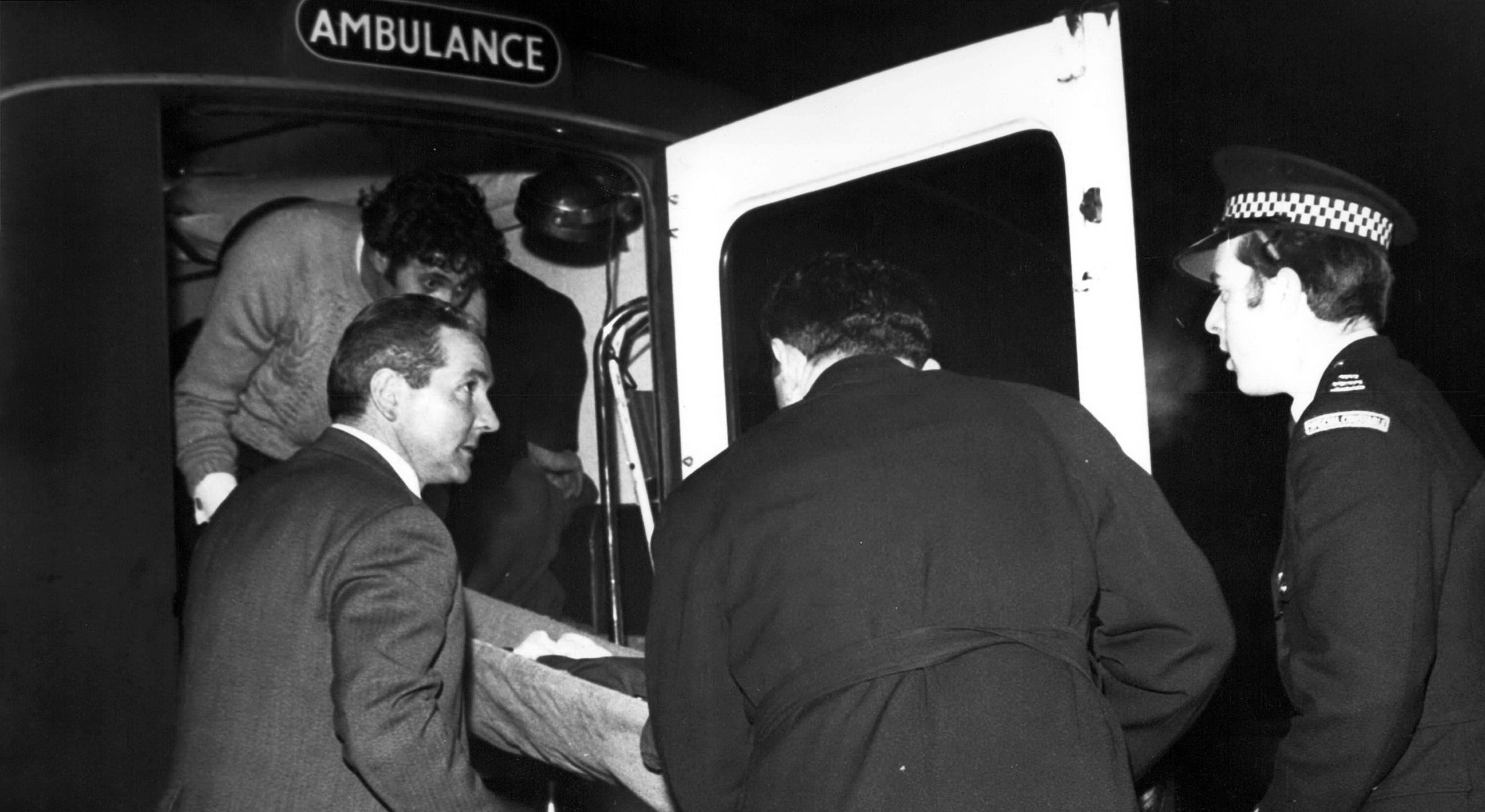

Celtic manager Jock Stein helps lift a man on to a stretcher.

Celtic manager Jock Stein helps lift a man on to a stretcher.

Those who fell were stacked on top of each other, limbs at all angles in a terrifying knot that stretched 30ft wide and 6ft tall. Robbed of the breath to shout for help, the heart of the crush fell silent.

Some died fully upright while those still able clawed for any give under the weight of the lifeless fans around them. Little blood was spilled and few limbs were broken, several witnesses described how the suffocated victims just looked as if they were sleeping.

The police eventually created a physical cordon across the top of Stairway 13 to try to relieve the pressure. Human chains then formed at the top and bottom of the stairway to pick off the dead and injured from the desperate chaos.

In his despatch for the Glasgow Herald newspaper, match reporter Andrew Young described how the shocked silence was occasionally interrupted by, “the noise of coins falling from the victims’ pockets as they were lifted away.”

Amid the confusion, Celtic manager Jock Stein and Rangers coach Jock Wallace worked as stretcher bearers, while Celtic assistant manager Sean Fallon, a former lifeguard, revived one young fan with mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

Injured fans were given aid at the side of the pitch.

Injured fans were given aid at the side of the pitch.

Ambulances began to arrive and one witness described a Celtic supporters’ bus taking the walking wounded to hospital. The dead were carried down the terraces and on to the pitch. A row of bodies was neatly laid out on the damp grass on the goal line before a makeshift mortuary was created in the dressing rooms.

When Stairway 13 was eventually cleared the full horror of what happened became clearer under the winter mist and sodium lamps overhead.

The twisted metal barriers, sprawled flat across four lanes, told their own story but equally compelling was the debris scattered on the steps. Shoes, socks, watches, glasses, combs and wallets – all forced from those caught in the pressure of the crush.

In a space barely bigger than an 18-yard box a total of 66 people had been killed. Five boys from Markinch were among the dead.

The metal barriers were crushed flat across four lanes of Stairway 13.

The metal barriers were crushed flat across four lanes of Stairway 13.

Glasgow hospitals were put on high alert as ambulances arrived from across the city.

Glasgow hospitals were put on high alert as ambulances arrived from across the city.

The dead were carried out and bodies laid out on the grass at the foot of the terraces.

The dead were carried out and bodies laid out on the grass at the foot of the terraces.

Three boys come home

Shane, Peter and Joe were on a Celtic supporters’ bus, stopped 28 miles from Glasgow at the village of Kincardine, when they first heard something had happened at Ibrox.

“It was where the buses usually stop, where the older ones want a pint of beer,” explains Shane. “When they came back onto the bus they informed us there had been an incident at Ibrox and there had been fatalities.

“At that stage we never thought for a minute that our friends from Markinch would be involved.”

The vast majority of fans who left the stadium that day were also unaware of the tragedy unfolding. News of an incident at Ibrox reached radio listeners but those at the game, even thousands who had used Stairway 13, were oblivious to the disaster.

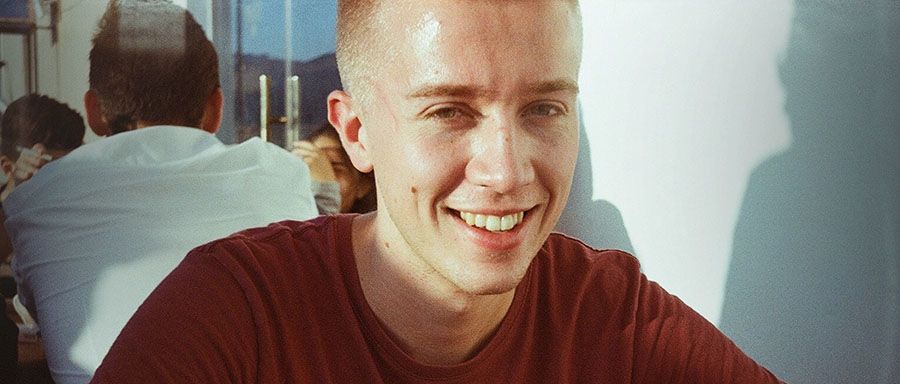

Shane Fenton, 67, had no idea the others hadn’t left the stadium.

Shane, 17, Peter, 16, and Joe, 14, arrived back in Glenrothes and retraced their steps along the dark country road to Markinch. They reached the neat rows of semi-detached council houses in their home street, Park View.

“When I walked through the door, the emotion - I’ll never ever forget that,” explains Peter. "Word filtered through that the Glenrothes bus had arrived but the boys from Markinch, none of them, had arrived back on it.

“At that point in time we thought they’d been caught up in the melee, they’ve missed their bus.”

Peter Lee, 66, hoped his Markinch pals were on the last train.

As the night wore on friends and family members of the eight boys gathered in Park View with hopes raised and dashed by telephones ringing and cars arriving. Close to midnight a group including Shane and Peter headed to the railway station to await the arrival of the last service.

“We were standing on top of the bridge at the station,” says Peter. “I could see in the distance, there was a light from the train through the fog.

“The train pulls up, the doors opened, one or two people disembarked, the doors closed and that was it. I’ll never ever forget that feeling.”

The next morning, the news feared in Markinch was confirmed. The five boys had been killed by the crush on Stairway 13.

A village in mourning

“Five boys that all lived together, played football together - we’re never ever going to see them again.” says Peter, now 66 years old. “As a young boy it was pretty hard to comprehend.”

“I’d never experienced tragedy or bereavement or anything like that in my life. I can’t even recall crying, because we were just too numb to actually shed any tears.”

Peter Easton, 13, Mason Philip, 14, Douglas Morrison, 15, and Bryan Todd, 14, all lived on Park View while Ronald Paton, 14, lived just round the corner. They were well-liked and known to nearly everyone in the street.

Shane, now 67, recalls how Peter Easton was the most academically gifted, Mason was the quietest of the group, Douglas could turn his hand to any sport, while Ronald Paton was the biggest football obsessive.

The Daily Express reported how Ronald had tossed a coin with his twin brother Ian to see who would take the one ticket they had for the supporters’ bus that day.

Bryan Todd’s brother Kevin was just five years old when it happened. His parents had been driving him on a trip to visit relatives in Herefordshire.

“We were halfway down and news broke on the radio of the disaster,” he explains. “So we pulled over and they were phoning back to get news of my brother.

“My mum and dad had to come back up and my dad had to go through to Glasgow with the other dads to identify the bodies. It was a tragedy that you could go to the football and not return.”

“To lose a child must surely be the most dreadful thing that can happen to any mother.”

For Peter Easton’s family, the numbness of the tragedy was mixed with regret. His mum Gisela told BBC Scotland in 2001 that his dad, Harry, was not keen to let their son go to Ibrox. But she won him over by arguing that Peter “deserves a treat”.

“I find it very difficult to put into words,” said Gisella. “My life as I had known it ended, it had to start again.”

"The sun had gone and I felt that I was sinking into a deep black hole. To lose a child must surely be the most dreadful thing that can happen to any mother.”

Thousands paid their respects at the funerals which followed, including players from Rangers and Celtic. Spittal’s, the local ironmonger on the route of the funeral cortege, replaced its window display with five footballs.

Bryan Gould, session clerk at Markinch and Thornton Parish Church, was 16 years old at the time of tragedy and remembers the impact it had.

“Very few houses had phones, so the news came by word of mouth that the five boys weren’t coming back,” he says.

“Death was what happened to old people, you weren’t aware of any of our own generation dying. And for five of them to die in the same event was incomprehensible.”

Local minister Reverend William Hastie Miller told a memorial service it had been a “black day for Scotland” and a “black, black day for Markinch”.

A black day for Scotland

The devastating news of a disaster where nearly half of the 66 victims were under the age of 20 resonated around Scotland. At that time most people knew someone who regularly went to football matches.

A Dunbartonshire mother of a 14-year-old boy, who regularly went to games with his friends, wrote a letter of condolence to Bryan Todd’s family saying she was aware, “it might have been their faces looking out at me from the newspaper this morning”.

Archbishop James Donald Scanlan, speaking at a requiem mass attended by both Rangers and Celtic players, talked of a “tornado of grief” hitting Glasgow. The tragedy also attracted international attention. US president Richard Nixon and Pope Paul VI both sent notes of condolence.

Rangers boss Willie Waddell led the club’s response and divided his squad up to ensure they would be properly represented at the victims’ funerals.

Rangers players Derek Johnstone, Colin Jackson and Dave Smith visit the injured in hospital.

Rangers players Derek Johnstone, Colin Jackson and Dave Smith visit the injured in hospital.

It was an intense period with 65 of the services taking place over four days, 20 of which took place in Glasgow on one day alone. Many Rangers players, some still teenagers, attended three or four funerals each. A huge fundraising drive for the victims’ families saw money come in from the football world and beyond.

It was a tragedy that also saw the Old Firm divide melt away. In the next edition of ‘The Celtic View’, the club’s official magazine, manager Jock Stein said the tragedy had to “help to curb the bigotry and bitterness of Old Firm matches”.

He added: “When human life is at stake then bigotry and bitterness seem sordid little things. Fans of both sides will never forget this disaster.”

“When flesh and bone meet steel and stone there can only ever be one winner”

There were many suggestions about the immediate cause of the fatal crush. One witness said that a young teenager, sitting on the shoulders of a man and waving his scarf around as they went down the stairs, had fallen.

Another claimed some of the crowd had turned around to get back to the terraces upon hearing the Rangers equaliser.

This suggestion was dismantled at the subsequent Fatal Accident Inquiry where one witness said to do so would have been like “running into a brick wall”. But it was a myth that was to endure for decades.

The 1971 crush was not the first serious accident on Stairway 13.

The 1971 crush was not the first serious accident on Stairway 13.

Rather more prosaically the inquiry concluded the disaster had been caused by “one or more persons falling”. Today’s experts have a better understanding of the dynamics of crowds.

Professor Keith Still - a world-renowned safety expert who was a technical advisor to the Hillsborough Inquiry - says it was “not necessarily a single trigger” that caused the accident.

“Literally anything, a misstep or somebody tripping over their own feet, could’ve caused it,” he says. “In a crowd that’s packed to the levels of density that eyewitnesses were commenting on at Ibrox, and on a slope, then you get gravitational force added to the fall.

“As each person falls onto others, then you get a cascade dynamic, and of course as soon as that hits steel, well when flesh and bone meet steel and stone there can only ever be one winner.”

BBC Reporter Andrew Picken explains how the Stairway 13 crush happened.

BBC Reporter Andrew Picken explains how the Stairway 13 crush happened.

Was anyone to blame?

The three Markinch boys who came home, Peter, Shane and Joe - who passed away in 2019 - never dwelled on what went wrong on Stairway 13.

“As far as I’ve been concerned it’s always been just a tragic accident and the five Markinch boys, with being youngsters and all together, got caught up in it,” says Shane.

But the inquiry and a subsequent civil legal case against Rangers showed this had not been the first problem on Stairway 13. There had been three serious accidents at the exit in the previous decade, including a crush in 1961 which saw two people die and 70 injured.

The club made changes to Stairway 13 after these earlier incidents, such as replacing wooden barriers with steel, but the fundamental design was not altered. Suggestions from the police and local council to change the steps to allow people to “fan out” instead of coming straight down, as well as replacing the side fence with a metal rail, were not acted upon.

Rangers manager Willie Waddell speaks to journalists at Ibrox.

Rangers manager Willie Waddell speaks to journalists at Ibrox.

In 1969 Rangers reinforced the side fence of Stairway 13 with concrete. This move was described by engineering firm Ove Arup in its evidence to the civil case as “hardly comprehensible”, as it had been the way fans escaped danger in previous crushes.

Arup also claimed the height and depth of the steps on Stairway 13 were unsafe “where the crowd pressure is likely to be at its highest”. But Rangers’ lawyers argued that the accident was caused by “unpredictable human conduct”.

A consulting engineer for Norwich Union, the club’s insurers, disagreed with Arup’s assessment and speculated that, “it seems to me the spectators created their own danger.”

Club officials went further in their submissions to the court, with one director arguing that Stairway 13 “seemed to us to be a good staircase,” adding that the accidents, “could have been created by elements in the crowd simply refusing to hold back and maintain some form of order amongst themselves.”

“The problems of crowd movements, pressures and flows was not generally appreciated prior to 1971”

Professor Keith Still says this instinct to blame the behaviour of those caught up in crushes is commonplace. “In nearly every instance it’s ‘blame the crowd’,” he says.

“If you look at all of the headlines of all of the major disasters, they will usually use those two words, ‘panic’ and ‘stampede’. Very rarely has that been the cause of the incident. It’s been a consequence of people reacting to a situation that they find themselves in.”

Professor Still adds that it was important to remember that much of the understanding of the dynamics of human crushes came decades after the Ibrox disaster.

“You cannot judge an event in 1971 by the science that we know and understand now,” he says. “Hindsight’s a wonderful thing. But at that time, this was common practice, there hadn’t been a disaster.”

Professor Keith Still talks to BBC reporter Andrew Picken.

Walter Winterbottom, the first England manager, led a review of sports stadiums after the Ibrox disaster. It took in 57 grounds across the UK, including 14 in Scotland. He made the same point 50 years ago.

In a letter held at the Mitchell Library archives in Glasgow, Mr Winterbottom said Rangers’ stadium was actually “above average” in terms of construction quality and he saw “several other stairways that potentially seemed more dangerous than the Ibrox one”.

But, crucially, Mr Winterbottom concluded it was the volume of people using this stairway which caused the accident, adding that the “nature of the problems of crowd movements, pressures and flows was not generally appreciated prior to 1971”.

Irvine Smith QC, the sheriff in charge of the civil case, ruled the accident was due to the negligence of Rangers and awarded £26,000 in damages to the family of one of the victims.

The sheriff was critical of Rangers’ directors in charge at the time of the disaster and said their attitude was as if “the problem was ignored long enough it would eventually disappear”.

Old Ibrox Stadium

Ibrox Stadium today

Rebuilding football

Two weeks after the disaster, with Stairway 13 boarded up, Rangers were back playing at Ibrox. The club’s immediate response was to implement the recommendations made before the 1971 tragedy.

A wall was built at the top of Stairway 13 to slow the flow of the crowd and the wooden fence which had pinned in so many of the victims was replaced with open railings.

But Rangers, under the vision of manager Willie Waddell, then embarked on a much more ambitious overhaul of the stadium to create a ground that the club later described as a fitting and lasting memorial to the 66 victims.

A decade after the disaster, Stairway 13 had been demolished and Ibrox was turned into the most modern stadium in the UK.

There were also wider changes in football. The Wheatley Report of safety standards at sports grounds ordered after the disaster led to the 1975 Safety of Sports Grounds Act.

This required councils to issue safety certificates for grounds – something which Scotland’s local authorities had requested six months before the Ibrox disaster but had been rejected by the UK government as offering only "marginal" benefits.

Football was beginning to treat supporters as people to keep safe rather than just under control. But even so, more tragedy was to follow in the shape of the Bradford and Hillsborough disasters before it got this right.

The scar is deep

Markinch today has expanded well beyond the footprint of the old village. Housing estates now hug the country road the eight boys walked to their football buses in 1971.

Shane, now a local sports reporter and window cleaner, says it took a long time for any sense of normality to return. He and Peter had just one more season going to Celtic games, before the memories became too much to bear.

Much of the work in recent years to ensure the Ibrox disaster is not forgotten has been supporter-led. Groups of Rangers fans have worked to build memorials and maintain graves in communities across Scotland touched by the disaster.

Rangers Football Club has never shied away from commemorating the events of 1971, holding an annual tribute to the victims. A memorial was built at Ibrox in 2001, with the names of the 66 dead below a statue of former captain John Greig.

The village memorial to the Markinch boys.

The village memorial to the Markinch boys.

But away from these diligent efforts it can be argued that the disaster has slipped from the national consciousness in recent decades. A tragedy from the black and white days.

In Markinch, a new generation of football-mad youngsters still make the short walk from Park View to John Dixon Park to play on its sloped grass. They pass a granite memorial, flanked by five rowan trees, to the dead Markinch boys. Shane, who still lives in the village, tends to it most weeks to keep it tidy.

“Back then it really left its mark but as time’s gone on interest has waned,” Shane says. “It seems the young people don’t know about it. All I want to do is keep it in people’s memories.”

Writing in the match programme for the next game after the 1971 disaster, Rangers manager Willie Waddell paid tribute to the “show of goodwill” in response to the tragedy.

It was the Old Firm game that didn’t matter. But he warned the “scar is deep”.

That is still true 50 years on for the survivors and families. They still remember the fans who went to the football one day and never came home.

Remembering the 66

Bryan Todd - Robert McAdam - Peter Wright - John Gardiner - Richard Bark - William Summerhill - George Adams - John Neill - James Trainer - Douglas Morrison - James Rae - David McGee -Robert Mulholland - Ronald Paton - George Irwin - Ian Frew - John Crawford - Brian Hutchison - Duncan McBrearty - Charles Livingstone - Adam Henderson - Richard McLeay - David Duff - David McPherson - Robert Rae - Robert Grant - John McLeay - David Anderson - John Buchanan - John Semple - John Jeffrey - Robert Maxwell - Matthew Reid - Alexander McIntyre - Peter Farries - Thomas Melville - John McGovern - George Wilson - Robert Cairns - Hugh Addie - James Mair - Margaret Ferguson - Robert Carrigan - George Smith -Walter Raeburn - Andrew Lindsay - Charles Dougan - Mason Philip - Thomas Morgan -Peter Easton - George Findlay - Charles Stirling - Thomas Dickson - James Gray - Thomas McRobbie - Ian Hunter - Nigel Pickup - Russell Malcolm - Alexander Orr - Thomas Stirling - James Sibbald - Francis Dover - Walter Shields - Thomas Grant - William Shaw - Donald Sutherland

Watch Disclosure: Stairway 13 on BBC iPlayer

Credits

Writer: Andrew Picken

Producer: Paul Hastie

Editor: Matt Roper

Images: Alamy, Getty, Glasgow Life, Google Maps, Eric McCowat, Mirrorpix, PA

Published December 2020