The fall of the god of cars

By Theo Leggett

with additional reporting by Rupert Wingfield-Hayes in Japan

When Carlos Ghosn flew into Tokyo’s Haneda Airport on a November afternoon in 2018, he was at the height of his powers.

He was the chairman of Nissan, the man credited with saving the Japanese carmaker from potential bankruptcy. He was also chief executive of the French carmaker Renault – and the driving force behind a global alliance between the two. Along with the smaller manufacturer Mitsubishi, they made up a motor industry group that sold more than 10 million cars a year.

November 2018: Nissan's company jet landing at Tokyo's Haneda Airport

November 2018: Nissan's company jet landing at Tokyo's Haneda Airport

He was used to dividing his time between Paris and Tokyo, not to mention regularly checking in on the group’s operations in North America. This globetrotting lifestyle came with perks, such as the use of a corporate jet. Brazilian born, raised in Lebanon and educated in France, he had close ties to all three countries, and had the use of luxury homes in Rio de Janeiro, Paris and Beirut, as well as Tokyo.

He arrived in Tokyo that day from Beirut. As his sleek corporate jet made its way across the airport tarmac it was easily identifiable by the registration emblazoned on the white engine nacelles - N155AN.

Ghosn was unaware of what awaited him inside the terminal.

On arrival, he says he was picked up by a car and taken to passport control, where he was informed that there was a problem with his visa. He was escorted to a small side room, where he was arrested, to be charged with serious financial crimes.

Within hours of landing, he was locked in a prison cell.

He was not the only target. Greg Kelly, one of Ghosn’s closest confidants, was apprehended separately after flying in to a different Japanese airport from the US - having been summoned to what he thought was an urgent meeting.

The 63-year-old US citizen was a “representative director” of the company and was officially charged with carrying out the board’s wishes. In practical terms, he was Ghosn’s enforcer. For health reasons, he had planned to join the meeting by video link. But according to his wife, the company insisted he attended in person - and arranged a private jet for him.

Following their arrests, the pair were taken to Tokyo’s Kosuge Detention Centre in the city’s north-east. It was here, in a tiny cell, that Ghosn would remain for the next four months. He was subject to daily interrogations, as prosecutors sought a confession from him.

Kelly, who suffers from spinal problems, was released on bail just over a month later – but not before his wife, Dee, had published a video message in the US in which she complained bitterly about his treatment at the hands of the Japanese authorities.

He remains in Japan awaiting trial – in many ways the forgotten man of the whole affair.

In March 2019, Ghosn was briefly released, having posted bail of $9m (£6.9m). But he was re-arrested on fresh charges before finally allowed to leave jail again in late April, on payment of a further $4.5m bond.

But there were significant restrictions on his movements, including an effective ban on seeing or communicating with his wife. Even when he was allowed to speak with her by internet link on Christmas Eve - a very rare privilege approved by the court - a lawyer had to be present, listening in.

Ghosn’s biographer Philippe Ries spent several weeks in Tokyo last year, meeting with him on a daily basis. He has spoken to him since his escape and thinks the way his wife was treated was a key factor in his decision to abscond.

Carole Ghosn - his second wife - had been Ghosn’s most vocal supporter. Early in his incarceration, she wrote an excoriating nine-page letter to the Japan office of Human Rights Watch, in which she railed against the “draconian” Japanese legal system. It allowed prosecutors, she said, to “interrogate him, browbeat him, lecture him and berate him” on a daily basis, without a lawyer being present.

April 2019: Carlos and Carole Ghosn in Tokyo

April 2019: Carlos and Carole Ghosn in Tokyo

When Ghosn was re-arrested in April, police raided his home in the early hours of the morning while the couple slept. Carole Ghosn later told the BBC that while her husband was being apprehended an officer had followed her through their apartment, and even stood watch while she took a shower.

“I think they wanted to intimidate and humiliate us,” she said. “This woman even handed me the towel.”

Carole Ghosn herself was later questioned by the authorities, ostensibly as part of the investigation into her husband’s business affairs. She was not charged at the time, but left the country soon afterwards. In December the Japanese authorities widened their inquiry to other family members, interviewing his son Anthony and one of his daughters in New York

“They went after his family, and he is a family man,” says Philippe Ries. “His family is very important to him.”

“I am certain that played a big role in his decision to try to escape.”

January 2020: Carole Ghosn at her husband's press conference in Lebanon

January 2020: Carole Ghosn at her husband's press conference in Lebanon

Throughout her husband’s time in jail, Carole Ghosn appealed to global leaders, including US President Donald Trump, the French President Emmanuel Macron and Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro to intervene on her husband’s behalf.

Escape

The details are still missing, but it is clear Ghosn’s escape from Japan was audacious, risky and well planned.

There was certainly nothing furtive about his departure from his Tokyo home. Around lunchtime on 29 December, he simply walked out of the building during the early afternoon.

With the country winding down for the New Year break, it is possible security measures were lighter than usual.

According to Japanese media reports, CCTV pictures show that he went to a nearby hotel, where he met two men. These are believed to have been Michael Taylor, a former member of the US Special Forces, who is now a private security contractor; and his Lebanese associate George-Antoine Zayek.

It’s thought that the three of them caught a bullet train from Tokyo to Osaka, a two-and-a-half-hour ride away.

It was a big risk. On that day, the train would have been crowded with holiday travellers. Ghosn was a very well-known figure and easily recognisable, so to reduce the danger, he wore a hat and covered his face with a surgical mask. Wearing such masks in Japan is considered entirely normal, a precaution to prevent the spread of coughs and colds.

On arrival in Osaka, the three men reportedly went to another hotel. A few hours later, according to broadcaster NHK, two of them left for the airport - but there was no sign of Ghosn. It is believed he was concealed in a large, black box-like luggage case, one of two they had with them.

At the airport, the case was loaded on to an aircraft. Ghosn would leave Japan just as he had arrived more than a year beforehand - aboard a private jet. But whereas he had flown in as an emperor of the auto industry, he left Japanese soil as a fugitive - hidden in a box.

That, at least, is the story which has been widely circulated. But in a lengthy interview in Beirut with the BBC’s John Simpson, Ghosn cryptically refused to confirm any details of his escape, beyond the bald fact that he had walked out of his front door in Tokyo.

When asked what it had been like hiding in a box, he laughed, before denying point blank such a thing had ever happened.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about. Probably the last time I was in a box, I was a kid, you know, when I was playing.

“I don’t have any memory of something like this, so I can’t comment on it.”

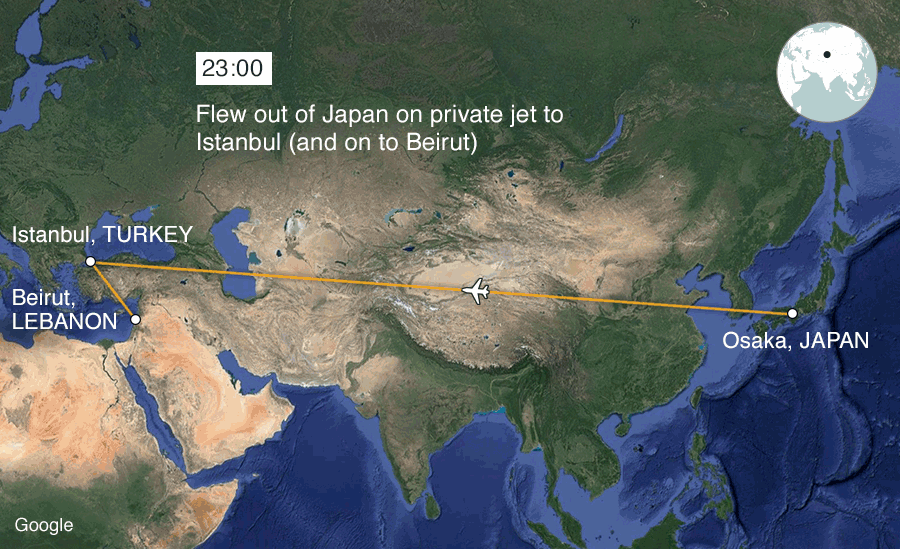

It has been reported that at around 23:00 on Sunday 29 December, the aircraft carrying Ghosn and his companions took off from Japan bound for Turkey.

In Istanbul, they switched planes. It was done discreetly – Ghosn certainly never officially entered the country. Shortly afterwards, they left for Beirut, on a second jet.

All of this, it appears, was done without the knowledge of the company operating the flights. MNG Jet says it leased two separate aircraft to two different clients, and that the two leases were apparently unconnected.

It insists that Ghosn’s name did not appear in any of the official paperwork. It has since launched an internal inquiry and filed a criminal complaint with the Turkish authorities over the illegal use of its services. It says one of its employees has admitted falsifying records.

Turkish officials, meanwhile, later detained seven people in connection with the affair, including four pilots working under contract for MNG Jet. It is not clear, however, whether the pilots actually knew about their unofficial passenger.

Despite his rather unorthodox travel arrangements, we know that Ghosn entered Lebanon perfectly legally, using a French passport and a Lebanese identity card.

Ultimately, whatever the consequences for those involved, the escape itself was an unqualified success. Carlos Ghosn was in Lebanon, celebrating the New Year with his wife, and preparing to protest his innocence to the world.

How Ghosn is thought to have escaped Japan on 29 December 2019

How Ghosn is thought to have escaped Japan on 29 December 2019

How Ghosn is thought to have escaped Japan on 29 December 2019

How Ghosn is thought to have escaped Japan on 29 December 2019

How Ghosn is thought to have escaped Japan on 29 December 2019

How Ghosn is thought to have escaped Japan on 29 December 2019

The details are still missing, but it is clear Ghosn’s escape from Japan was audacious, risky and well planned.

There was certainly nothing furtive about his departure from his Tokyo home. Around lunchtime on 29 December, he simply walked out of the building during the early afternoon.

With the country winding down for the New Year break, it is possible security measures were lighter than usual.

According to Japanese media reports, CCTV pictures show that he went to a nearby hotel, where he met two men. These are believed to have been Michael Taylor, a former member of the US Special Forces, who is now a private security contractor; and his Lebanese associate George-Antoine Zayek.

It’s thought that the three of them caught a bullet train from Tokyo to Osaka, a two-and-a-half-hour ride away.

It was a big risk. On that day, the train would have been crowded with holiday travellers. Ghosn was a very well-known figure and easily recognisable, so to reduce the danger, he wore a hat and covered his face with a surgical mask. Wearing such masks in Japan is considered entirely normal, a precaution to prevent the spread of coughs and colds.

On arrival in Osaka, the three men reportedly went to another hotel. A few hours later, according to broadcaster NHK, two of them left for the airport - but there was no sign of Ghosn. It is believed he was concealed in a large, black box-like luggage case, one of two they had with them.

At the airport, the case was loaded on to an aircraft. Ghosn would leave Japan just as he had arrived more than a year beforehand - aboard a private jet. But whereas he had flown in as an emperor of the auto industry, he left Japanese soil as a fugitive - hidden in a box.

That, at least, is the story which has been widely circulated. But in a lengthy interview in Beirut with the BBC’s John Simpson, Ghosn cryptically refused to confirm any details of his escape, beyond the bald fact that he had walked out of his front door in Tokyo.

When asked what it had been like hiding in a box, he laughed, before denying point blank such a thing had ever happened.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about. Probably the last time I was in a box, I was a kid, you know, when I was playing.

“I don’t have any memory of something like this, so I can’t comment on it.”

It has been reported that at around 23:00 on Sunday 29 December, the aircraft carrying Ghosn and his companions took off from Japan bound for Turkey.

In Istanbul, they switched planes. It was done discreetly - Ghosn certainly never officially entered the country. Shortly afterwards, they left for Beirut, on a second jet.

All of this, it appears, was done without the knowledge of the company operating the flights. MNG Jet says it leased two separate aircraft to two different clients, and that the two leases were apparently unconnected.

It insists that Ghosn’s name did not appear in any of the official paperwork. It has since launched an internal inquiry and filed a criminal complaint with the Turkish authorities over the illegal use of its services. It says one of its employees has admitted falsifying records.

Turkish officials, meanwhile, later detained seven people in connection with the affair, including four pilots working under contract for MNG Jet. It is not clear, however, whether the pilots actually knew about their unofficial passenger.

Despite his rather unorthodox travel arrangements, we know that Ghosn entered Lebanon perfectly legally, using a French passport and a Lebanese identity card.

Ultimately, whatever the consequences for those involved, the escape itself was an unqualified success. Carlos Ghosn was in Lebanon, celebrating the New Year with his wife, and preparing to protest his innocence to the world.

What went wrong?

At his peak, Ghosn was a titan of the motor industry, the creator of one of the most powerful car-making groups in the world.

In France, he was “Le Cost Killer”, the ruthless executive who turned Renault around when it was ailing in the late 1990s. In Japan, he was the outsider who had been parachuted in to rescue Nissan from the brink of bankruptcy – and in the process became a national celebrity.

In both cases, he took on established institutions and rode roughshod over vested interests, closing factories and cutting jobs in the short term, but paving the way for future growth and profitability.

The two companies were linked under a strategic alliance first forged in 1999, and were joined in 2016 by the smaller Japanese firm Mitsubishi. By 2017 the group was collectively producing more than 10 million vehicles a year. Ghosn, as chief executive of Renault and chairman of the two Japanese firms, remained the linchpin of the entire project. But trouble was brewing.

Feathers had already been thoroughly ruffled in Nissan’s Yokohama headquarters by decisions taken in Paris.

The French government is a shareholder in Renault, and in 2015 it managed to double its voting rights in the company, significantly increasing its influence over boardroom decisions. For Nissan this mattered a great deal, because Renault is not only its partner, but also its biggest single shareholder.

To put it simply, this meant that political decisions taken in France, and with French interests at heart, could have a significant impact on Nissan.

By 2018, the French government was making its increased influence felt. Ghosn was handed a renewed mandate, giving him another four years as chairman and chief executive of Renault. But he was under intense pressure from Paris to make the alliance “irreversible”.

What he planned to do, as he confirmed at a press conference in Beirut in early January, was to create a new structure for the combined business. There would be a single holding company in which shares would be traded. This would own both Renault and Nissan. But the two brands would continue to be run as separate businesses, with their own headquarters and maintaining their distinct identities.

Ghosn also wanted to bring the Italian-American carmaker Fiat Chrysler into the Alliance, turning it into a truly formidable global manufacturer.

But in Japan, it is clear all of this was greeted with the deepest suspicion.

Former Nissan chief executive Hiroto Saikawa

Former Nissan chief executive Hiroto Saikawa

Insiders say Nissan bosses such as chief executive Hiroto Saikawa were already feeling vulnerable due to a decline in the company’s performance. Stronger links with Renault, they thought, would undermine their own authority and their autonomy. Nissan could become just an outpost of an international group - shorn of its Japanese identity.

Ghosn’s own view is that these concerns were shared by members of the Japanese government, who later became involved in manoeuvres against him. Whether or not that is true, it is clear that by mid-2018 nerves at Nissan were on edge - and that without his knowledge, Ghosn’s position had become precarious.

Plot?

Ghosn and his lawyers claim that his arrest was the direct result of a plot involving senior Nissan executives and members of Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, which aimed to remove him as leader of the Alliance, and stop him forging stronger links between Renault and Nissan.

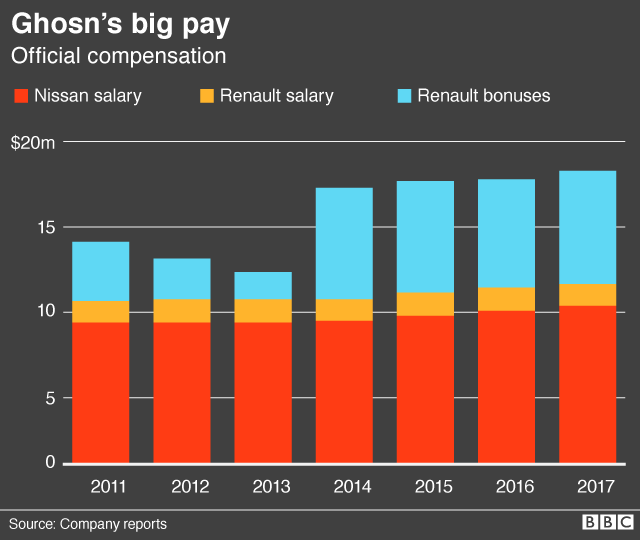

He was initially charged with breaking Japanese law by under-reporting his salary over a four-year period, to the tune of $44m (£33.7m). Kelly was also indicted for failing to report his chief executive’s full earnings.

This allegation was later extended, taking the total to more than $80m over eight years. It concerned deferred salary, to be paid after Ghosn’s retirement. He says the money was never received, and would have had to be approved by the Nissan board, which never happened.

The issue attracted the attention of US market regulators. In September 2019, the Securities and Exchange Commission reached a settlement with Ghosn, Kelly and Nissan itself over allegations that compensation of $140m had been left out of financial disclosures. Fines were paid - in Ghosn’s case $1m - but there was no admission of wrongdoing.

In the months that followed, other charges of “breach of trust” were added. Ghosn was accused of abusing his position for personal gain, by temporarily shifting personal investment losses to Nissan, and using company funds to pay a Saudi business associate, Khaled al-Juffali, $14.7m.

He was also later accused of siphoning off $5m funds paid to a Nissan distributor in Oman, Suhail Bahwan Automobiles, and retaining them for personal use. Carole Ghosn was later questioned over claims that diverted funds were used by a company she controlled to buy a luxury yacht.

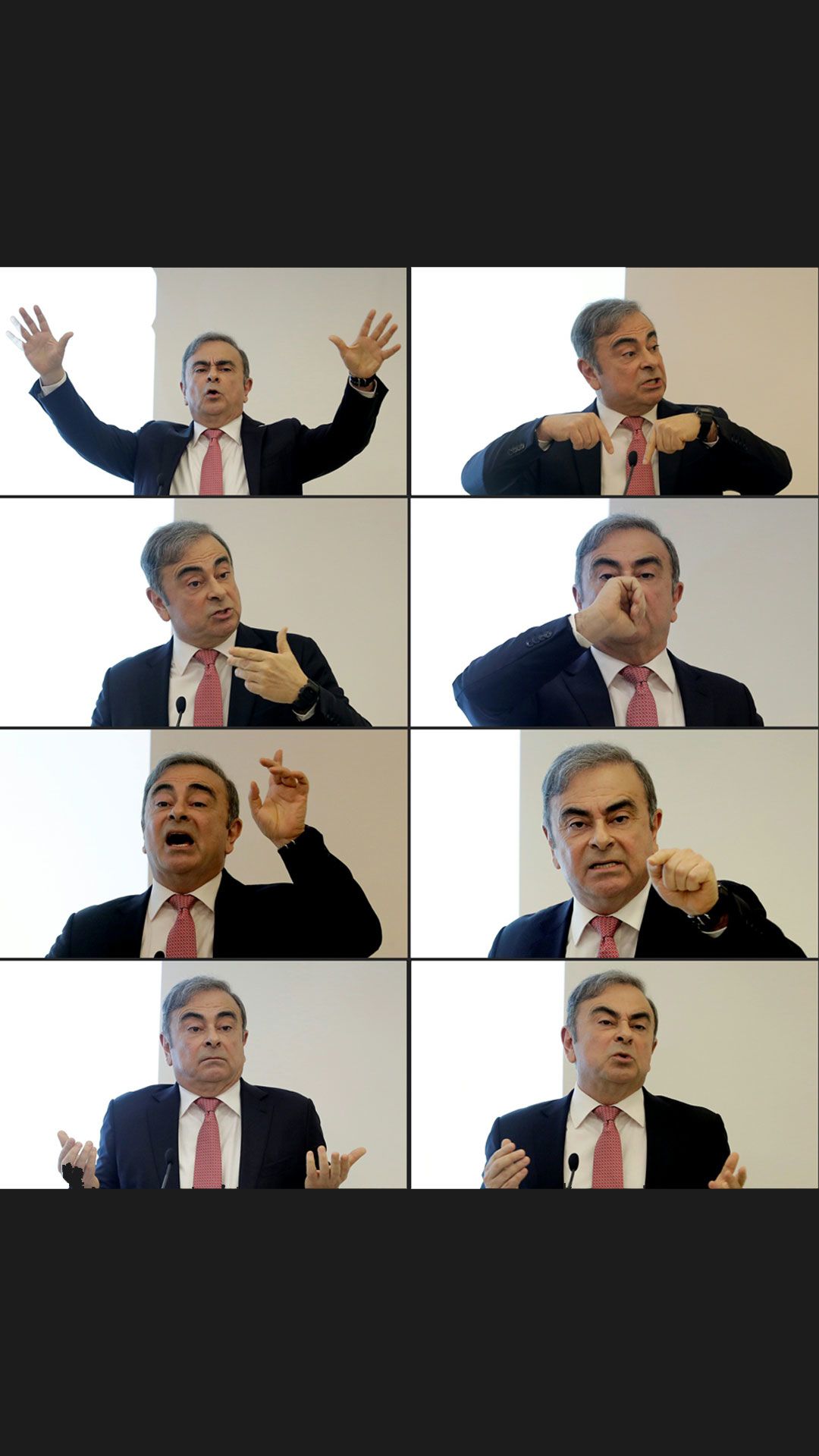

Ghosn insists that the transactions were all above board, and that he is innocent of all these charges. At his press conference in Beirut, he railed against the Japanese judicial system, which he said “violated the basic principles of humanity”. He condemned the “vindictive inglorious individuals” he claimed had conspired against him.

He also promised to publish internal documents from Nissan which he said would help prove his case.

The company itself, meanwhile, insists it “discovered numerous acts of misconduct by Ghosn through a robust, thorough internal investigation”. It adds that it found “incontrovertible evidence of various acts of misconduct by Ghosn, including misstatement of his compensation and misappropriation of the company’s assets for his personal benefit”.

The allegations have yet to be tested in a court of law. But according to Ghosn’s supporters, they provided ample ammunition to a group of executives hell-bent on bringing him down.

January 2020: Ghosn at his press conference in Beirut

January 2020: Ghosn at his press conference in Beirut

Central to the investigation was Hari Nada, a British-Malaysian businessman in his 50s. A senior vice-president at Nissan, he had worked closely with Ghosn and Kelly. Insiders say that for many years he was seen as being deeply loyal to them.

But in 2018, his loyalties appear to have changed. He took information about Ghosn’s financial dealings to the authorities - and subsequently began working with them to investigate further, having agreed a plea bargain to protect his own position.

Ghosn’s lawyers claim the whole process was a sham, and that senior Nissan executives, prosecutors and members of the government deliberately colluded in an effort to prevent further integration between Renault and Nissan.

At his press conference, Ghosn implicated a number of senior figures within Nissan, who he accused of conspiring against him - among them Hiroto Saikawa, the chief executive at the time of his arrest, and his former protégé.

Nissan Motor Co headquarters, Yokohama

Nissan Motor Co headquarters, Yokohama

However, Ghosn refused to say who within the government had been part of the “conspiracy”, citing the sensitivity of relations between Lebanon and Japan as a result of his escape. Questioned by the BBC, he said, “I don’t personally think that the top level was involved… I don’t think [Prime Minister] Abe-san was involved.”

In response, Saikawa told reporters he had been “a bit disappointed” by Ghosn’s allegations.

“He was my trusted boss and we were heavily betrayed by him once,” he said.

“And this time I feel I have been greatly betrayed by him a second time.”

99.4% conviction rate

By Rupert Wingfield-Hayes

Many people, including Ghosn, have appeared genuinely surprised that Japan’s justice system is so different from those of other democratic countries. They shouldn’t have been. Any long-term resident of Japan will tell you the one thing that makes them uneasy about living in this otherwise peaceful and friendly society, is the power of its police and public prosecutors.

There are numerous stories of foreigners getting caught up in a drunken argument or traffic dispute, a punch being thrown, and then of spending the next three weeks in police detention. But it is wrong to think that foreigners are singled out for this sort of treatment. The reality is, prolonged detention without charge in Japan is the norm.

To its critics, the Japanese system is known as “hostage justice”.

Ghosn was held, in total, for 128 days but there are many Japanese who have been held much longer.

Lawrence Repeta is a constitutional law professor who has spent many years teaching in Japan and fighting for legal reform.

“Look at the case of [Hiroji] Yamashiro,” he says. “He was held for 153 days.”

Hiroji Yamashiro was a leader of protests against the construction of a new US military base in Okinawa. In 2017, he was arrested after he tried to block the entrance to the construction site. He was held in isolation for more than five months before being charged.

Environmental protester Hiroji Yamashiro

Environmental protester Hiroji Yamashiro

“Then there’s the Moritomo Gakuen case,” Prof Repeta says, naming another high-profile scandal that hit the headlines here in 2017. He says the couple at the centre of that case were held without charge for 299 days.

“Very, very long detentions before trial are the norm in Japan,” he says, “and during those detentions suspects will be interrogated for up to eight hours a day.”

People can be held for an initial period of 23 days without charge, during which time they will only be allowed to meet their lawyer. They can be interrogated for many hours a day without the presence of legal counsel. It is a system that has been widely criticised, including by the United Nations Human Rights Commission, but Japan’s justice ministry remains unmoved.

At a recent meeting with senior justice ministry officials, I asked why Japan has refused to bring its pre-charge detention system into line with other democratic countries.

“Interrogation serves a very important function in the Japanese judicial process,” the senior official said. “It has been decided by senior legal experts that the presence of defence counsel during interrogation would impair the advancement of the interrogation process. But the defendant’s right to remain silent is guaranteed.”

“Japan’s constitution says you have the right to remain silent,” says Prof Repeta. “But the reality is, it is denied. The prosecutors will scream at you, say you are a cockroach who is betraying Japan. There is no lawyer present, you are berated for eight hours a day, for 23 days, with no hope of it stopping.”

This certainly fits with what Ghosn has claimed he experienced; of being daily pressured in to making a confession, of prosecutors saying they would go after his family if he didn’t confess.

All legal systems make efforts to get those accused of crimes to confess. But critics of Japan’s system say it takes the pressure to confess to a different level.

Former prosecutor Nobuo Gohara says the problem with Japan’s public prosecutors is they think they are infallible.

Inside a cell in the Tokyo Detention Center, where Ghosn was held

“People point to Japan’s 99.4% conviction rate and make a misjudgement,” he says. “In fact police drop about 30% of the cases that they investigate. That means only 70% proceed to prosecution.”

He says prosecutors generally only go ahead if they think the evidence for conviction is overwhelming.

“So, the prosecutors think they are right,” he says. “And because they think they are right, they think a confession in front of the prosecutor is the right thing for the defendant to do. And having a defence lawyer present just gets in the way of the defendant making the correct confession.”

March 2019: Ghosn (in blue hat) being led from custody

March 2019: Ghosn (in blue hat) being led from custody

This, according to Gohara, is why Japanese prosecutors take such a dim view of those who deny guilt, and why they will often re-arrest a suspect on slightly different charges once the initial 23-day period is over. Then the process of interrogation can begin all over again.

But this is not the only aspect of Japan’s judicial process that sets it apart. As Ghosn found out, even when bail is granted, Japan’s prosecutors can demand some extraordinary conditions. In Ghosn’s case the most obvious was the court’s decision that he could not meet or even communicate with his wife.

Prosecutors say Carole Ghosn was closely tied to the case, and she could have assisted her husband in destroying evidence. We do not know what evidence they presented to back this claim.

“International law is clear,” says Prof Repeta. “Family members should not be kept separate.”

Even defenders of the Tokyo prosecutor’s office struggle to explain the decision on Carole Ghosn.

Former prosecutor Yasayuki Takai has criticised those who say Ghosn couldn’t get a fair trial in Japan. He says Ghosn’s performance at his press conference in Lebanon was that of “a comedian”. But asked if it was justified to keep the couple apart he is more ambivalent.

“It’s not the case that if he had stayed in Japan he wouldn’t have been able to see his wife,” he tells me. “His lawyers needed to do a better job of convincing the court.” But he says that if he were the prosecutor running this case, he would have allowed Ghosn to see his wife.

Most of those I have spoken to, those who defend Ghosn and those who criticise him, have expressed frustration and disappointment in his decision to flee.

For former prosecutor Nobuo Gohara it is a missed opportunity to expose the faults of Japan’s system.

“I wanted him to fight this case. I share the view of his lawyers that there was a high possibility he could win, that the evidence against him was weak.”

Yasayuki Takai described the case as “very unpredictable” one which was being prosecuted under a “new and untested law”.

“So the chance of acquittal is higher. If Ghosn had attended the trial properly and presented his case clearly there is a probability of a not guilty verdict. But he fled.”

Nobuo Gohara is more sympathetic. “The first trial would have taken one and a half years before the second trial on other charges could even begin. So, it could take four or five years to get a verdict.”

And according to Prof Repeta, even if Ghosn won, his legal problems might not be over.

“Ghosn had the best lawyers, all the advantages. He could have won,” he says. “But then the prosecutors could appeal the acquittal all the way up to the Supreme Court. And in many cases in Japan acquittals are overturned on appeal. A reasonable person in Ghosn’s position, if they could escape, I think they would do it.”

The man

“I was called a cold, greedy dictator,” said Mr Ghosn, seething with anger as he described his treatment at the hands of the press in Japan and elsewhere.

Since his arrest, he has come under fire over his lavish lifestyle - his luxury houses funded by Nissan, not to mention the lavish party he threw for his wife at the Palais de Versailles to celebrate her 50th birthday. Certainly, Ghosn is not short of critics. But others have rallied to defend his character.

Born in Brazil to Lebanese parents, he spent most of his childhood in Beirut. His university education, at the prestigious Ecole Polytechnique in Paris, followed by the equally distinguished engineering school, the Ecole des Mines, should have given Ghosn a direct passport into the close-knit world of the French elite.

Ghosn with Emmanuel Macron in 2014 - the current French president was economy and industry minister at the time

Ghosn with Emmanuel Macron in 2014 - the current French president was economy and industry minister at the time

Ghosn's rapid rise through the business world at Michelin, Renault and Nissan won him armies of admirers. He was viewed as the archetype of “Davos man”, the kind of jetsetting alpha-executive who liked to rub shoulders with world leaders. But according to his biographer, Philippe Ries, appearances can be deceptive.

“He was always an outsider,” Ries says. “He never cultivated political connections. He was invited on dozens of presidential foreign trips. Never went on a single one. Not a single one. He refused to play that game, and of course they hated him for it.”

Ries knew Ghosn well when working alongside him in Japan during the early 2000s. He describes an engaging, courteous man whose company he seems to have enjoyed.

At the Cannes film festival, 2017

At the Cannes film festival, 2017

Fifteen years later, he renewed the acquaintance while Ghosn was on bail in Tokyo. The two spent several weeks working together on a new book.

I asked him if he thought Ghosn’s character had changed.

“I listened to all that stuff about how he had become a greedy dictator, and I said, maybe his ego had got the better of him and he has become a completely different person.”

It wasn’t the case.

“Circumstances had changed,” says Ries. “But he was exactly the same man, 15 years older.”

The image of Ghosn as an autocratic leader, whose underlings were too scared of him to report any alleged wrongdoing they found, has also been challenged by former associates.

He would certainly keep underperforming executives on a tight leash, one insider told me, but those who were good at their jobs would be given plenty of autonomy.

My own impressions of Ghosn, having met and interviewed him many times over the years, were mixed.

At major events, such as motor shows, I became used to the way in which his subordinates seemed rather overawed by his presence. Arrangements had to be made, and stuck to rigidly. Last-minute changes were frowned upon.

He was often accompanied by a large retinue, sweeping onto the stage in regal fashion. The interviews themselves were always businesslike, sometimes bland, but occasionally he would drop in a small bombshell, which he knew would create instant headlines. Then, on to the next meeting.

Most of the time, he certainly fitted the picture of the imperious CEO. Yet when I met him in London at short notice, he turned up without the retinue. He was open, friendly, and happy to chat freely. He only became guarded once the cameras had been turned on. At those moments, the alpha executive looked more like a role to be performed.

But, as his recent Beirut press conference showed, it is a role he appears to enjoy.

What now?

Japan has obtained an international request for Ghosn's arrest through Interpol and put diplomatic pressure on Lebanon. But there is no extradition treaty between the two countries.

There are other factors to consider as well. The BBC’s John Simpson points out that “given the huge pride and sympathy people in Lebanon have displayed for Carlos Ghosn, the chances that the government here will agree to extradite him to Japan are vanishingly small”.

One possibility, according to legal sources, is that he could stand trial in France. That country does not normally extradite its own citizens, and Ghosn has French nationality. Moreover, under the French legal system, its citizens can be tried for crimes committed abroad.

What makes this scenario more plausible is that Ghosn is already being investigated by the French authorities. His home near Paris was searched by police last year, as they looked for evidence of potential financial wrongdoing.

His former employer, Renault, has highlighted 11m euros (£9.3m, $12.2m) of questionable expenses. He denies wrongdoing.

Legal experts say this inquiry could potentially be broadened to include the allegations made against Ghosn in Japan.

The house in Beirut where Ghosn is now based

The house in Beirut where Ghosn is now based

People within the Ghosn camp insist he would welcome the opportunity to stand trial.

“He wants his legacy to have value,” says one. “He needs to clear his name in order to protect his legacy.”

But a substantial part of that legacy seems to be evaporating.

Renault and Nissan have seen their profits tumble since his departure. Tens of billions of dollars have been wiped from the market value of both companies. Intense boardroom battles have led to the chief executives of both companies - one of them Saikawa - being ousted.

The Alliance limps on. The deep structural connections between the two companies cannot easily be got rid of, but the prospect of deeper integration between them seems dead in the water.

Ghosn, himself, is clearly a much-diminished figure. But he has not lost hope of turning his fortunes around, however.

“I am used to what you call Mission Impossible,” he told journalists. “I don’t consider I’m in a situation where I can’t do anything. I want to clear my name.”

One thing he is not planning to do is disappear into obscurity. When John Simpson asked him if he had any plans to retire, he was emphatic.

“Oh no!” he said. “There are a lot of challenges ahead. It’s not time for retirement!”