Why Amazon knows

so much about you

By Leo Kelion

You might call me an Amazon super-user.

I’ve been a customer since 1999, and rely on it for everything from grass seed to birthday gifts.

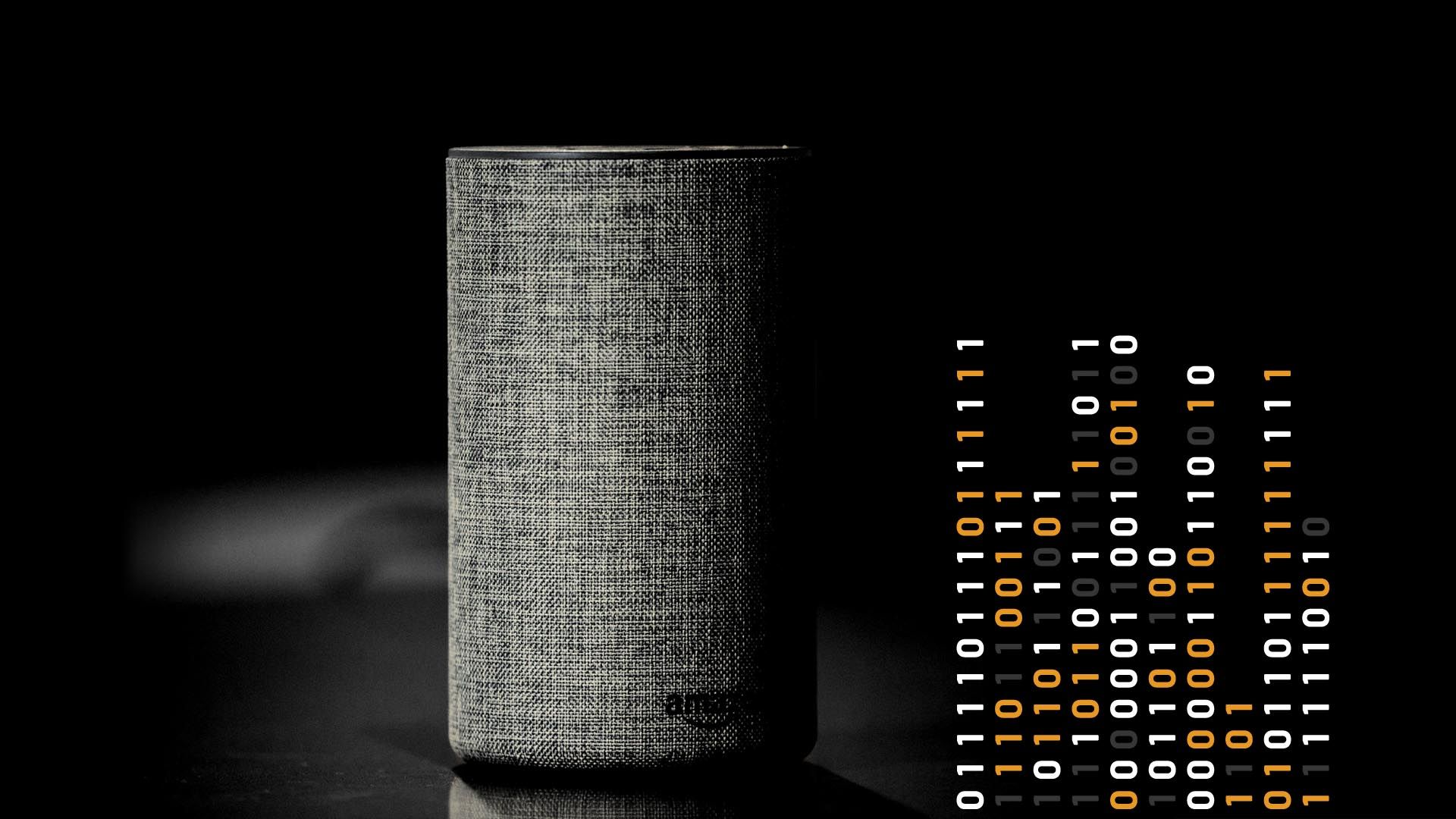

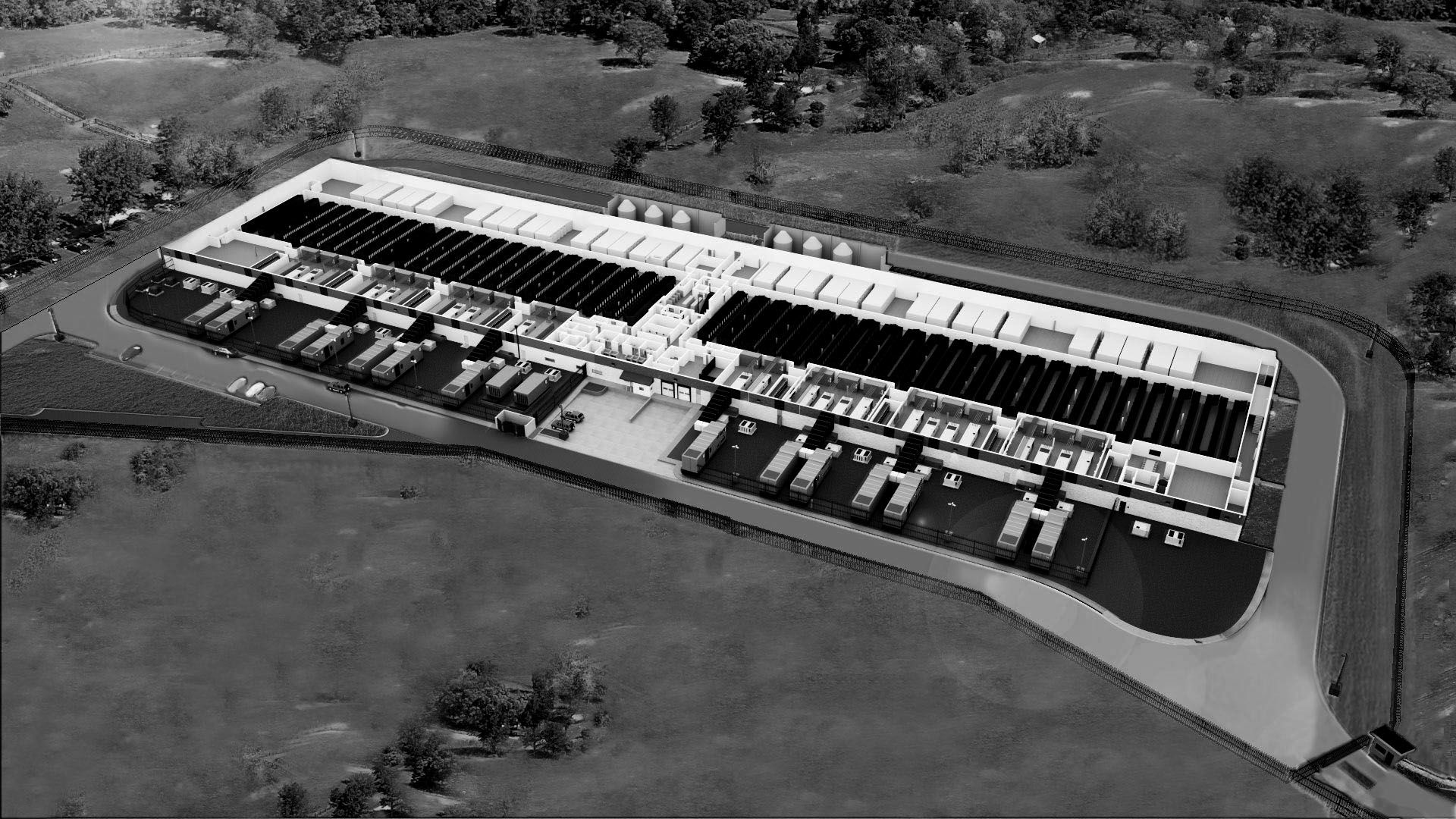

There are Echo speakers dotted throughout my home, Ring cameras inside and out, a Fire TV set-top box in the living room and an ageing Kindle e-reader by my bedside.

I submitted a data subject access request, asking Amazon to disclose everything it knows about me

Scanning through the hundreds of files I received in response, the level of detail is, in some cases, mind-bending.

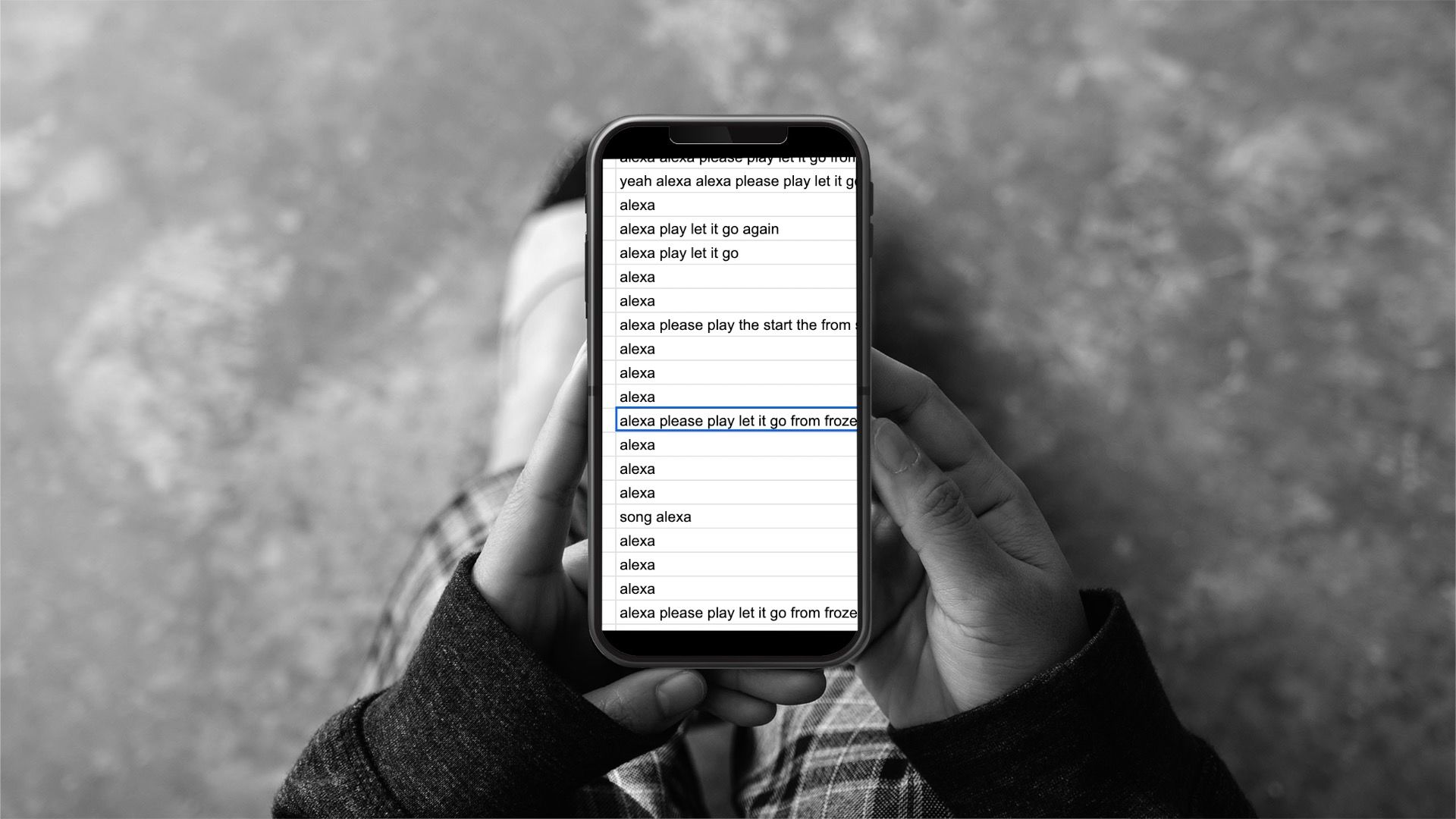

One database contains transcriptions of all 31,082 interactions my family has had with the virtual assistant Alexa. Audio clips of the recordings are also provided.

The 48 requests to play Let It Go, flag my daughter’s infatuation with Disney’s Frozen.

Other late-night music requests to the bedroom Echo, might provide a clue to a more adult activity.

Clicking on another file reveals 2,670 product searches I had carried out within its store since 2017. There are more than 60 supplementary columns for each one, containing information such as what device I’d been using, how many items I subsequently clicked on, and a string of numbers that hint at my location.

One spreadsheet actually triggers a warning message saying it is too big for my software to handle. It contains details of the 83,657 Kindle interactions I’ve had since 2018, including the exact time of day for each tap. An associated document divides up my reading sessions for each e-book, timing each to the millisecond.

And on it goes.

The endeavour was timed to coincide with a BBC Panorama documentary I’ve been involved with, which tracks Amazon’s rise through the prism of it being a data-collector.

“They happen to sell products, but they are a data company,” says James Thomson, one of the former executives interviewed.

“Each opportunity to interact with a customer is another opportunity to collect data.”

Founder Jeff Bezos frames it in terms of being a “customer obsession”, saying the firm’s first priority is to “figure out what they want, what's important to them”.

And he qualifies this by saying Amazon mustn’t violate people’s trust in the process.

Yet as the company continues to grow, and expand into new activities, there are calls from both inside and outside Amazon to keep its data-feasting obsession in check.

Getting to know you

Sleeping Lady resort is about a two-hour drive from Seattle.

The name comes from the shape of the mountains that tower above its wooden cabins.

When Bezos bussed Amazon’s staff there for a brainstorm in January 1997, it lived up to its Icicle Road address. A storm meant some missed the first evening’s events.

But they’d all arrived when their leader began the next morning’s session, saying he wanted to create “a culture of metrics”.

James Marcus was an in-house book reviewer at the time.

“This mania for quantification was in Jeff’s heart,” he says.

Marcus was grouped with Bezos at the event, as teams scribbled equations on white boards trying to invent ways to measure customer enjoyment.

“Jeff’s algorithm wasn’t that much better than anybody’s algorithm that day,” he says.

“But he understood that data was in fact very valuable.

“The idea that every mouse click and every twist and turn through the website was itself a commodity, was a new sort of thinking for most of the employees - and for me too.”

The next challenge was to decide what to sell beyond books.

They picked CDs and DVDs. Over the years, electronics, toys and clothing followed, as did overseas expansion.

And all this time, Amazon was building a battalion of data-mining experts.

Artificial intelligence expert Andreas Weigend was one of the first.

Before joining, he had published more than 100 scientific articles, co-founded one of the first music recommendation systems, and worked on an application to analyse online trades in real-time.

Amazon made him its first chief scientist.

“I had weekly meetings… with people, whoever wanted to stop by, where we just looked at clickstream histories in the evening, with beer and pizza, to wrap our brains around why would people actually do this, why on Earth would they click here,” he remembers.

Clickstreams are the digital breadcrumb trail which Amazon follows to see which sites users come from, how they travel through its own pages and where they go to next.

(Amazon’s response to my data request didn’t contain my own clickstream history, although the firm has provided such records to others in the past. A spokesman could not explain why.)

A savvy ad-tech specialist was among Weigend’s recruits.

David Selinger quickly climbed the ranks to lead the new Customer Behavior Research unit.

Bezos, Weigend (centre) and Selinger (right). Weigend: "I don’t know how that picture happened, I know that picture is in my bedroom in my bed at my home and nobody really is clear how Jeff Bezos got in my bed"

Bezos, Weigend (centre) and Selinger (right). Weigend: "I don’t know how that picture happened, I know that picture is in my bedroom in my bed at my home and nobody really is clear how Jeff Bezos got in my bed"

“Our job was to build a customer-based dataset and then prove that there were opportunities, kind of fissures of gold,” Selinger says.

Once a week they too delved into individuals' behaviour.

“We had to make it actionable,” Selinger continues.

“So to do that, we would project on the wall this view [of a] single customer and try to understand who she was.

“What was unique about the internet and Amazon at the time was that we were able to take each individual customer and then change the experience.”

Their work gave rise to personalisation and targeted recommendations, such as a customised front page for each user, and tailored emails in their inboxes.

“I was shocked to see how predictable people are,” says Dr Weigend.

“We didn’t think of it as exploiting, we thought about helping people make better decisions.”

Weigend and Selinger moved on, but Amazon continued to hire talent to find innovative ways to turn data into dollars.

Among them was ex-banker James Thomson.

“I had worked for other companies where there was a so-called data warehouse,” says the former Amazon Services business chief.

“But Amazon’s is literally the largest.

“Amazon knows not just your preferences but the million other preferences of customers that look a lot like you.

“So Amazon can basically anticipate what you’re going to need next - size up the inventory of which brands they are going to need in three to six months when you are ready to ‘unexpectedly’ buy those products.”

It used to be exotic to talk of “big data”. These days the buzz phrase is “artificial intelligence”.

However you frame it, Amazon leads the way in finding patterns in the noise of customer behaviour.

But while this fuels its profits, it has also prompted concerns about the elevated positions Bezos and his deputies enjoy as a result.

“We find ourselves being shot backward into a kind of feudal pattern where it was an elite, a priesthood, that had all the knowledge and all the rest of the people just kind of groped around in the dark,” says Shoshana Zuboff, a Harvard professor and author of The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.

“This narrow priesthood of data scientists and their bosses sits at the pinnacle of a new society.

“They are not beholden to us as customers, because in the surveillance capital model we are not customers, we are sources of raw material.”

Your brand,

our customers

Not all of Amazon’s big decisions have been based on data.

Sometimes Jeff Bezos simply goes with his gut.

At the turn of the millennium, he wanted a logo revamp.

The old logo showed the website’s address above a simple downturned swoosh.

A package design agency pitched the idea of turning the curve upside down to form a smiling arrow pointing from A to Z.

Bezos instantly loved it and rejected the need for consumer-testing.

“Anyone who doesn’t like this logo doesn’t like puppies,” he said.

Source: versionmuseum.com

Source: versionmuseum.com

The logo not only made Amazon seem friendly, but also highlighted its “everything store” ambitions.

Trying to stock everything on its own was out of the question. So, instead it went into business with its competition.

One after another, Amazon convinced bigger companies to outsource their e-retail operations to it.

ToysRUs, Borders, Waterstones, Marks & Spencer and Target were among household names to sign up.

The deals boosted everyone’s earnings in the short term, but Amazon was also making a longer-term play - it recognised the value of its partners’ data.

John Rossman headed up the initiative for a time. “At that point people didn’t understand the potential for e-commerce and digital business, and they essentially just viewed it as, ‘Hey here’s additional revenue,’” he recalls.

“They really gave away the keys to a kingdom.”

Under a strategy named Launch and Learn, Amazon first partnered with rivals, then studied their sector’s value chain, and finally expanded onto their patch.

It was years before the older firms realised the value of what they had given away.

Some collapsed. Others extricated themselves in time but regretted their error.

“They learned a tonne on our dime, and we didn’t learn much,” Target’s ex-chief strategy officer Carl Casey later complained.

The other side to Amazon’s strategy was to convince smaller third-parties to sell new and used items via Marketplace - a platform which allowed their goods to be listed on the same pages as its own stock.

It had a slow start, but became a massive success.

“Third-party sellers are kicking our first-party butt,” the firm gleefully disclosed in its last annual report, referring to the fact that since 2015 independent sellers have accounted for the majority of physical goods sold via its site.

Part of Marketplace’s success is down to Amazon’s willingness to share increasing amounts of analytics with the sellers.

But only Amazon gets complete access.

“Whether you're Target or another big retailer, or whether you’re a small entrepreneur who set up a third-party seller account, in all situations you’re basically renting the Amazon customer,” explains Thomson.

“In the end, Amazon collects all that data - and it stays within the Amazon database.”

For many merchants this is an acceptable trade-off.

Lavinia Davolio says Amazon made it possible to sell her luxury Lavolio sweets across the world, as well as afford a London store.

“The main benefit of the Amazon Marketplace is that my product suddenly is more visible to millions and millions of customers,” she says.

But when pushed, she acknowledges: “We can’t really communicate directly to them - the customer stays with Amazon.”

Most customers are probably happy that sellers can't bombard them with follow-up messages.

However, when things go wrong, merchants can feel like they’ve little recourse.

Roland Brana’s motorcycle clothing business boomed after he joined Amazon.

After years of solid sales, it persuaded him to deepen their relationship and form a retail-manufacturer partnership. In simple terms, he would focus on supplying his Bikers Gear UK goods and Amazon would take care of the selling.

Things started well, but then orders dried up.

When Brana logged in, he saw something odd - Amazon’s site showed it had recently taken in new stock, but he had not supplied it.

“This really sounded the alarm bells,” he remembers. So, he made a test purchase.

And on ripping open Amazon’s cardboard packaging, his worst fears were confirmed.

Within were biking clothes that resembled his designs, but with a different logo. They had been made by a factory he had previously used but ditched.

He tried to resolve the case directly with Amazon to get sole control of the Bikers Gear product pages, including their user reviews.

But he says he failed. And facing mounting debts, he decided to walk away.

“Through my experience it felt like I was battling with the devil,” he comments.

Panorama - Amazon: What They Know About Us

Amazon says that “based on information we received it is our understanding that Mr Brana was a reseller of the products”. It says the difficulties in which he had found himself were the result of a dispute between him and his original manufacturer.

Amazon’s UK chief Doug Gurr adds: “58% of all physical units that Amazon ships globally are from Marketplace sellers.

“So what you can see is that hundreds and thousands of small entrepreneurial businesses and tens of thousands of small entrepreneurial British businesses have been able to find in some cases extraordinary success.”

But the matter didn’t end there.

A year and a half ago, investigators from the EU’s competition commission made a surprise call.

“It was quite refreshing to finally have someone who was interested,” Brana says.

In fact, he is just one of about 1,500 merchants Margrethe Vestager’s team of watchdogs has contacted.

The European Commission has since launched a formal investigation.

The Danish enforcer tells Panorama her focus is to decide whether Amazon is using its Marketplace data “in an unfair way”, particularly with regards to how it picks who gets featured in a page’s prominent “buy box” - a position Amazon often inhabits itself.

“We would never accept in a football match that one team was also judging the game,” explains Vestager.

“Amazon gets the details of all the retailers and all the shopping that takes place. What you look at, what you look at but don’t buy, what you look at next, how you pay, how you prefer your shipping. All of that rich data.

“And you, as the individual retailer, you don’t.”

The commission has the power to fine firms up to 10% of their annual global turnover - a potential $28bn penalty in this case - and demand changes.

“Our approach is if Amazon is dominant in this market, they have this special responsibility not to misuse their power,” the commissioner adds.

Beyond

the web

Jamie Siminoff knew the numbers didn’t add up.

The inventor was on reality TV show Shark Tank to pitch DoorBot - a camera-enabled doorbell that let owners answer via their smartphone.

“Think of it as caller-ID for your front door,” he said, triggering a laugh from one of the panel of potential investors.

One by one the venture capitalists dropped out, until only one remained.

He made an aggressive offer, asking for not just a stake, but also a share of sales.

Siminoff declined.

“It’ll bleed us of cash,” he said before exiting the stage.

“I remember… literally being in tears - I needed the money,” he later remarked.

It proved to be a wise calculation.

Five years later Amazon swooped in and bought the business - now rebranded as Ring - for $839m (£643m).

Ring is part of a wider push by Amazon into services.

It also offers new ways to track people’s behaviour.

Ring’s privacy notice states that personal information is used to “perform analytics including market and consumer research….[and to] operate, evaluate, develop, manage and improve our business,” via in-house tools as well as third-party services.

(I asked Ring for my data to see exactly what this involves, but it has yet to provide it.)

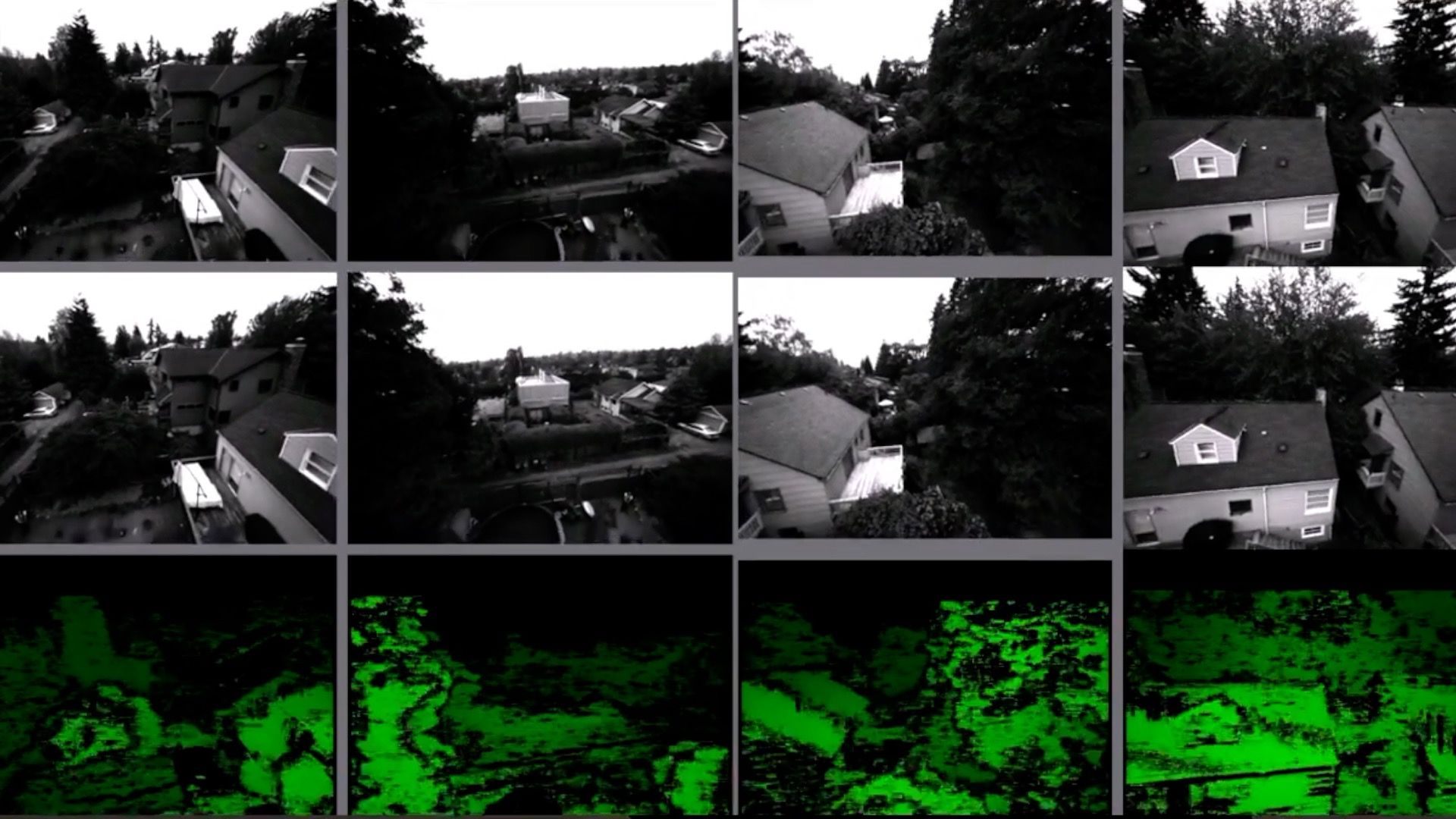

While much media coverage of Ring has centred on concerns it is helping the police to create a “surveillance state”, campaigners have recently turned their attention to the data it gathers about owners.

“Even when this information is not misused and employed for precisely its stated purpose (in most cases marketing), this can lead to a whole host of social ills,” claims the Electronic Frontier Foundation, which carried out a recent study.

Ring counters that the data helps it to deliver better experiences.

Those experiences will soon include Alexa.

Later this year, the virtual assistant will be able to tell delivery drivers where to leave a package or take a message for the homeowner, if they do not reply themselves.

And even smart devices that don’t have Alexa built in, can typically be controlled by it - and in turn provide Amazon with further details about users’ day-to-day activities.

“It’s moving unbelievably quickly,” says Daniel Rausch, Amazon’s smart home vice president.

“In just the first four months of [2019] we went from 30,000 to 60,000 devices that Alexa is compatible with.”

He adds that privacy and security are “at the heart” of the initiative.

For example, Alexa-enhanced devices light up to show when they are in listen mode.

(It’s worth noting that my data request turned up about 1,400 recordings that appear to have been accidental activations.)

Over time, Amazon has made it easier to review and delete voice histories.

You can now also opt out of letting humans listen back and check recordings to improve the service.

But Prof Zuboff raises concerns about whether people realise just how rich this new stream of data is.

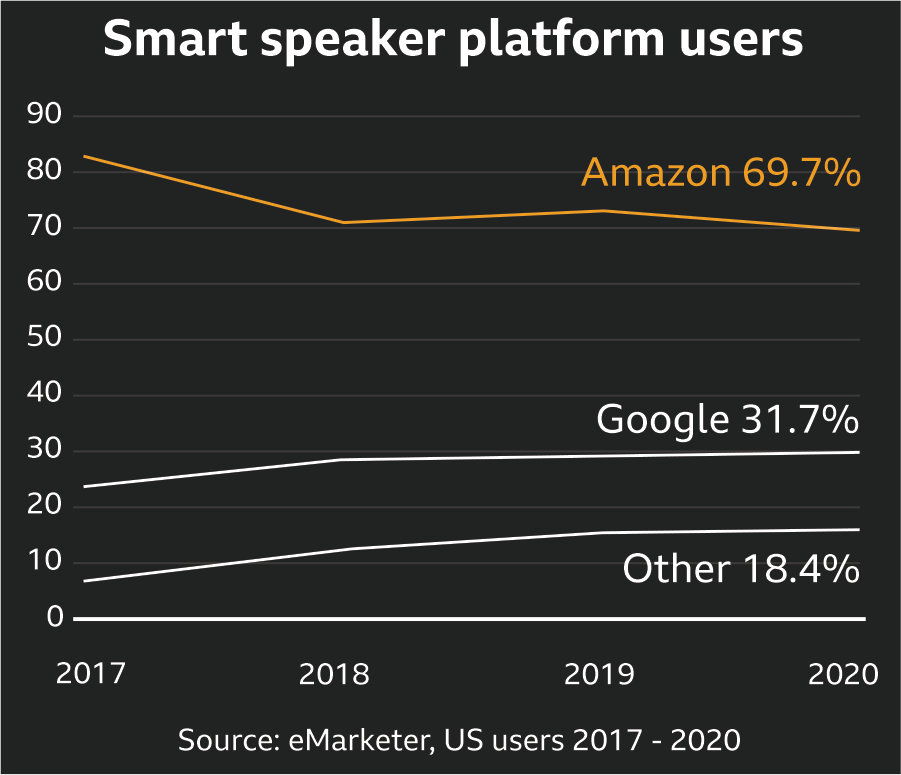

Some people use more than one platform, so the figures total more than 100%

Some people use more than one platform, so the figures total more than 100%

“From voice one can learn so many things about what a person cares about. What they’re thinking, how they’re engaging with their family, what their emotional state is,” says the psychologist.

“There are also ways of breaking down and doing voice analysis, where you get things like cadence and pitch and all these other very fine-grained variables that give us insight into human emotion and sentiment.

“These things are very highly predictive of future behaviour.”

Amazon is open about the fact it is developing speech-emotion detection - and has even made some of its research public. But its scientists suggest much work still needs to be done before it can be deployed.

Even so, sceptics say there’s a bigger point: consumers are scattering internet-connected microphones and cameras across their homes without necessarily thinking through the implications.

“We all need private spaces where we’re not observed,” says venture capitalist Roger McNamee, who first met Bezos in the mid-90s when he sat in on a pitch Amazon’s leader made to a Silicon Valley fund.

“Somewhere we can be our true selves without fear of being exposed or being exploited.

“It is the business strategy of Amazon with Alexa, but also with Ring doorbells, to take these sanctuaries and convert them into public spaces.

“People think: ‘Hey I give up a little personal data for a service I really like.’

“There was a time when that was [true]. But what’s going on now is much more invasive and much more manipulative.”

Amazon, however, says this misrepresents its efforts.

Devices chief Dave Limp says if it ever betrayed its customers, they could switch to a rival. Alexa might be the market leader, but it’s far from being the only AI on call.

“We all have phones in and around us, and they can do all the [same] things,” he says.

“They can wake up when you say their wake-words, they have cameras on them. So that world exists.”

And he adds: “We don't collect data for data's sake.”

“We would collect data on behalf of customers when we think we can invent something new for them or we can build a feature or service that benefits them in positive ways.”

Amazon everywhere

Today, many of the data-interpreting techniques pioneered by Amazon have become commonplace.

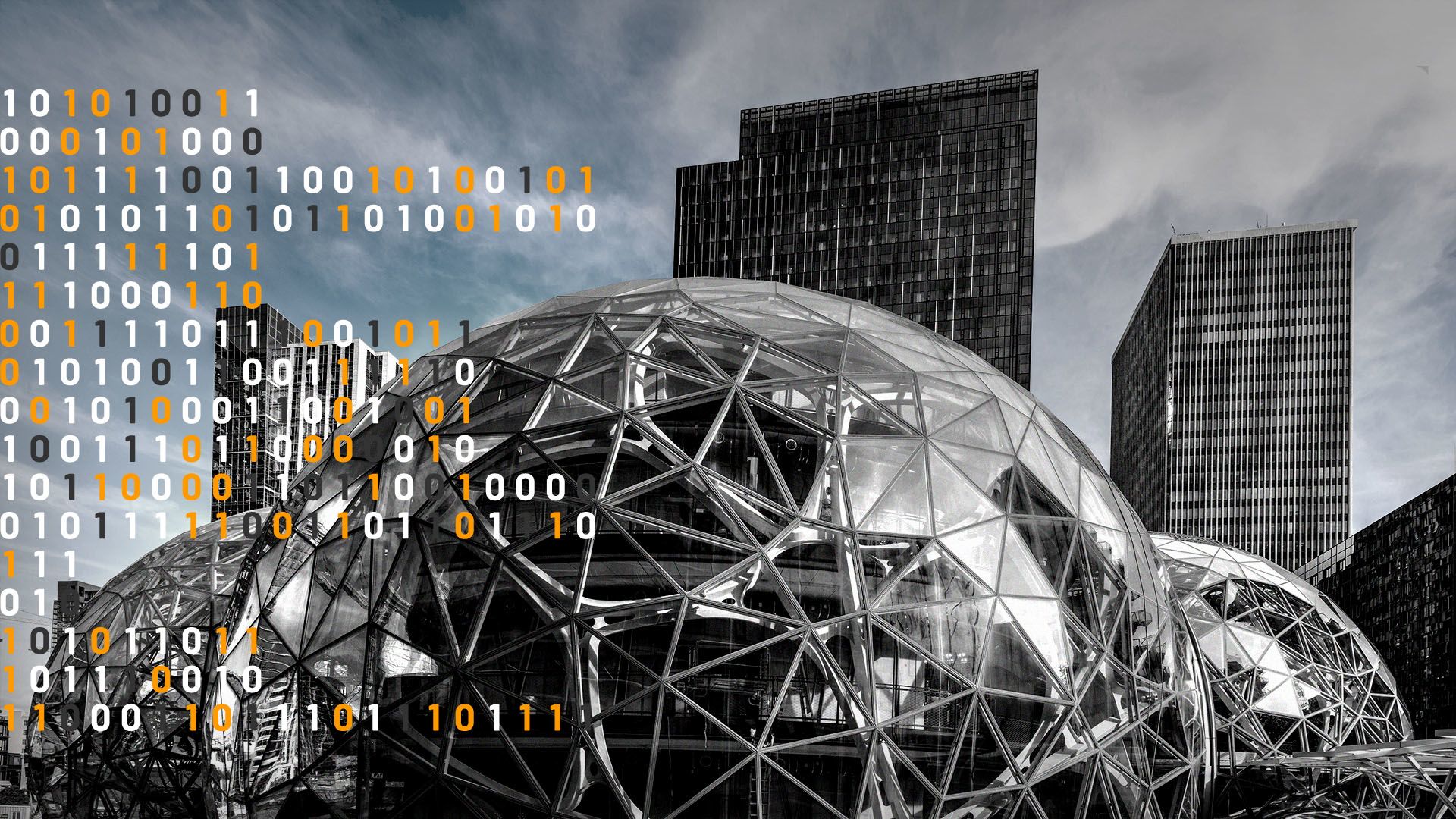

That’s in part because it built a business - Amazon Web Services - around selling them.

It began as a small initiative to share know-how with other website operators.

AWS’s first product manager, who had presented the idea to Amazon’s leaders, recalls that it nearly didn’t get off the ground.

"They thought it was giving away all of our intellectual property,” Robert Frederick says.

“People were saying: 'No, no, let’s not do it.'

“And [Jeff] said: ‘You know what? Let’s do it and let’s let them surprise us.’”

Developers were soon asking AWS to offer them computing power and storage in addition to tools for specific tasks, so it expanded.

Frederick likens this to providing the roads and electricity grid for a new country, saving individual enterprises the bother.

“Other companies didn’t need to basically go through and recreate everything themselves,” he explains.

The CIA and the UK’s Ministry of Justice are now among AWS’s many clients. So are some of Amazon’s biggest rivals, including Sainsbury’s, Apple, Netflix and the BBC. They trust the firm’s assurances that it can’t peek into their data.

As a consequence, it’s now practically impossible to go about the day without enriching Amazon in some way.

“I bet it’s not impossible,” jokes Matt Garman, one of AWS's current leaders.

“You could probably live in a cave or something like that.”

To stay ahead of its rivals, AWS continually rolls out new tools.

One, a facial recognition service called Rekognition, has become deeply controversial because it has been promoted to law enforcers.

It’s not clear how many are using it.

But one Oregon-based Sheriff’s office confirmed it’s using the tool to match images obtained of suspects against those of 300,000 mug shots it holds.

“Nobody will ever be arrested or detained simply based on a facial-recognition result,” one of its officers says.

But civil right activists claim it could lead to wrongful arrests.

It’s proved so contentious that some of the tech firm’s own employees wrote Bezos a protest letter.

“We know that [government] agencies surveil and monitor activists,” one told Panorama, asking to remain anonymous.

“The wider deployment of facial recognition has a real potential to curb freedom of speech and erase civil liberties.”

Amazon says it is mindful of such issues, and would support new regulations so long as they also apply to other providers.

“We’ve never had any reported misuse of law enforcement using the facial-recognition technology," says AWS chief Andy Jassy.

“Simply because the technology could be abused in some way, doesn’t mean that you should ban it.

“We believe that governments and the organisations that are charged with keeping our communities safe, have to have access to the most sophisticated, modern technology that exists.”

But one British watchdog fears where this could lead.

“If the technology of reading people’s lips and understanding what people are saying becomes commonplace, what effect will that have on people?” asks Tony Porter, surveillance camera commissioner for England and Wales.

“There are new technologies emerging that can perhaps monitor heartbeats.

“It amounts to a very real power to understand, to surveil you in a way you’ve never been surveilled before.”

Billion dollar

ideas

“I want to leave you all with a little glimpse of Amazon’s future,” says Jeff Wilke.

Dance music starts pounding through the vast room, cueing an unusually-shaped drone to rise from the stage.

It’s the climax to Amazon’s consumer chief’s presentation at an AI-themed conference in Las Vegas.

The aircraft’s wings double up as protective shrouds, he explains, so packages can still be transported in gusty conditions, and they also muffle its buzz.

But a fortnight later there’s a twist when a patent emerges revealing the company has considered using its delivery-drones to offer add-on surveillance services, such as scanning properties from overhead to advise how they could be better protected from intruders.

Amazon rarely lets a data-gathering opportunity go to waste. But the Prime Air initiative also underlines its willingness to make expensive long-term bets.

“We've had three big ideas,” Bezos once said.

“Put the customer first. Invent. And be patient.”

He arguably missed a fourth: Pay-offs should be gigantic.

“Nobody wants to get involved - unless you’re going to create a multi-billion dollar business,” explains ex-insider James Thomson.

“Multi-million dollar businesses are a dime a dozen.”

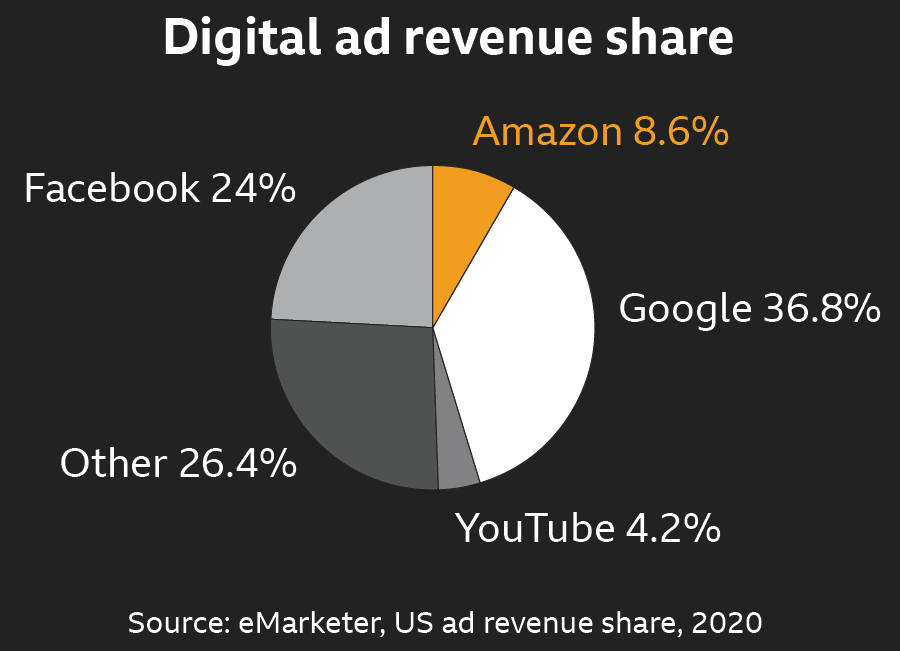

While Amazon waits for its drones to take off, advertising is helping to drive its current growth.

It was the fastest-growing segment on the firm’s latest balance sheet, and the company now ranks as the US’s third highest-earning digital ads player, behind Google and Facebook.

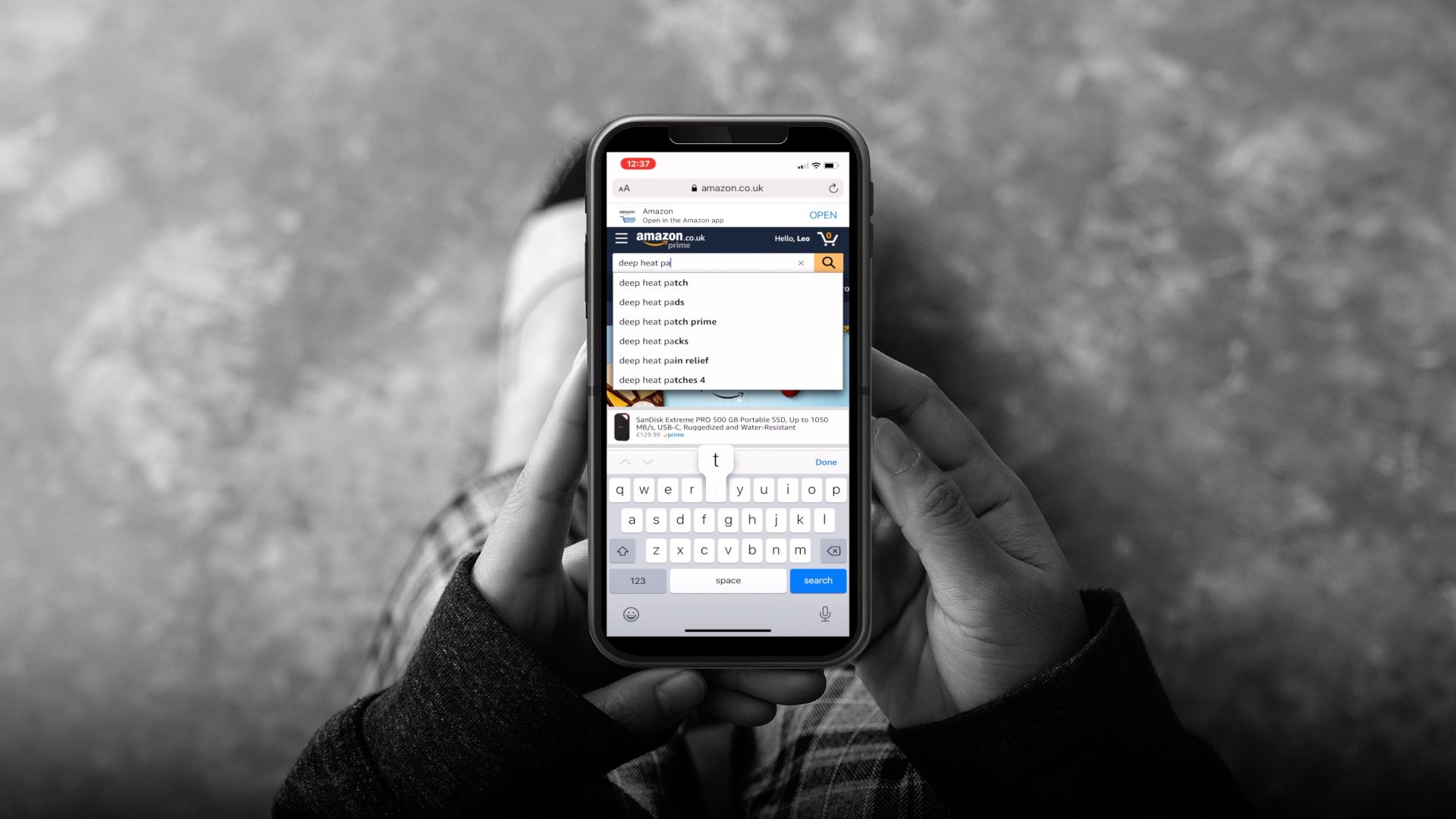

Much of the action occurs on Amazon’s own website.

It’s why when you search for a specific brand, rival products often take precedence on the results page.

Referred to as "sponsored items”, they sometimes crowd out the item you'd looked for unless its maker bid the most to stay on top.

Companies also compete for places on rival products’ sales pages.

Amazon claims its first priority is still to provide its customers with a useful and relevant experience.

So, while it shares data about what keywords are most popular, it doesn’t reveal what individual users are looking for or any of their other personal details.

But at least one ex-executive has doubts about the scale of the business.

“It’s great to see the other big digital advertising platforms have some competition,” comments John Rossman.

“But I do think there are fair questions about the balance.

“The top of the list is always advertising-driven. It’s not truly like the highest-rated product or the product that serves my history the best.”

There’s also been a backlash from smaller companies.

They complain they must now pay to keep their products “above the scroll”.

And that means either allowing their own profit to be squeezed, or passing on the extra cost to customers.

US competition watchdogs are currently probing Amazon’s treatment of its smaller suppliers, and this could be a flashpoint.

Searching for "deep heat patch"

So, what’s next?

Last year Amazon began a health insurance experiment, offering plans to its own workers and those of a bank via a joint venture called Haven Healthcare.

It also acquired PillPack, an US online chemist, and trademarked Amazon Pharmacy in the UK and dozens of other countries.

John Doerr - one of Amazon’s first investors - believes Bezos is laying the foundations for a new multi-billion dollar division.

“Imagine what it’s going to be like when he rolls out Prime Health, which I’m convinced he will,”he told a Forbes Media conference.

James Thomson worries how Amazon might use all that it knows to run this.

He describes a message it might send a patient it already provides cholesterol medication to.

“You weigh 225lbs, you have Lipitor prescription.

“You buy exercise equipment that apparently you don’t use because you never replace it.

“You don’t buy very many vegetables because we have all of your grocery shopping history.

“We’ve got products for that.”

And he predicts this would be a trigger point.

“When those types of things start to happen, I believe it will become much more apparent that we have a major major data problem here,” he says.

People love convenience and Amazon has prospered by obsessing about how to anticipate our wants before we’re even aware of them.

So, society now has a choice: continue letting Amazon learn ever more about us in the name of better service, or consider forcing it to divide up its data - and maybe even itself - to prevent it knowing too much.