The danger in our homes?

In 2015, Whirlpool revealed that millions of tumble dryers were potentially dangerous.

A series of blazes has led to major questions over the safety of home appliances.

The Garnhams

The tumble dryer in the Garnham family home was on the list.

It needed a simple alteration by an engineer, but the Garnhams had been told it was fine to use it while they waited.

Susan Garnham, a quietly spoken grandmother, was worried and says she rang Whirlpool several times.

More than a year later the company finally called back to book the engineer’s visit.

“You're a bit too late,” she told them. “My house has already burnt down.”

It was a chilly January evening in 2016 when Susan went home to her Guildford council house after visiting a craft fair at the nearby racecourse.

The healthcare assistant had thrown a few things into the washing machine before she left, and now put them into the dryer before cooking dinner.

Upstairs, her husband Graeme, a cleaner, was just about to get in the bath.

It was the smell that came first. Each thought the other had left something on the stove.

“Then I saw smoke in the corner of the kitchen diner,” Susan says. “I ran over to the dryer and saw flames.”

Her husband was downstairs by then.

We lost lots and lots of priceless things, but in some respects we have been very lucky

“I started to fill a bucket of water. That wasn’t a good idea,” he says. “By the time I had filled it up, the room was filling with black smoke. It was everywhere. I knew we had to get out.”

They left the house. Graeme was in just his underwear and his son's jacket, which he had grabbed on the way out. Outside, a neighbour lent him a pair of trousers.

“I was stood there in my bare feet, at the bottom of the alleyway, watching it all go up. The windows were popping out,” he says.

“I just couldn't talk.”

Graeme Garnham

Graeme Garnham

The fire started in the tumble dryer before spreading across the kitchen and the rest of the house, according to Surrey Fire Service investigators.

Victims of house fires often say it’s photographs that they miss the most when a home is gutted. That’s certainly true of the Garnhams.

“Thirty years of memories were gone,” Susan says. “We don't have any photos of our wedding anymore. It was 33 years ago at Guildford Register Office.”

Pictures of their children - James, Jason, Natasha, Chelsea and Kerry - had also been lost to the flames. They only have a single frame of family portraits on the wall now, borrowed from Susan's father.

Graeme is a keen Chelsea fan. One of the children is named after the team, another after 1980s star striker Kerry Dixon. Mementoes of decades of support all went up in flames.

“It happened so quickly. We weren't allowed back in,” says Susan.

In their late 50s and homeless, along with their sons who had also lived in the house, they were put up by the council in a nearby Travelodge.

They stayed for three weeks before moving into another council property.

They knew the house - partly because Graeme used to clean the windows there, but mostly because it overlooked the gutted remains of their old home just a few yards away.

The view of the Garnhams' old house from their rented property

The view of the Garnhams' old house from their rented property

The view was a reminder of what they had lost - so was their bank balance.

“We had kept on saying we have got to get insurance, but we did not have the money,” Susan says.

The family are still waiting for compensation, reliant on the outcome of a claim being made against Whirlpool by lawyers representing the council’s insurers. That has yet to be resolved. Whirlpool will not comment on the case.

Relatives rallied around the family, lending money for replacement furniture. Friends also set up a JustGiving page which raised more than £800 to help out, alongside other local collections.

The couple are grateful that their fate was not considerably worse.

“We used to put the dryer on in the middle of the night, whenever we needed it. Thank God we didn't that time,” Susan says.

“We lost lots and lots of priceless things, but in some respects we have been very lucky.”

Design flaw

“For more than a century, Whirlpool has been doing the right thing,” the company says in one of its promotional videos.

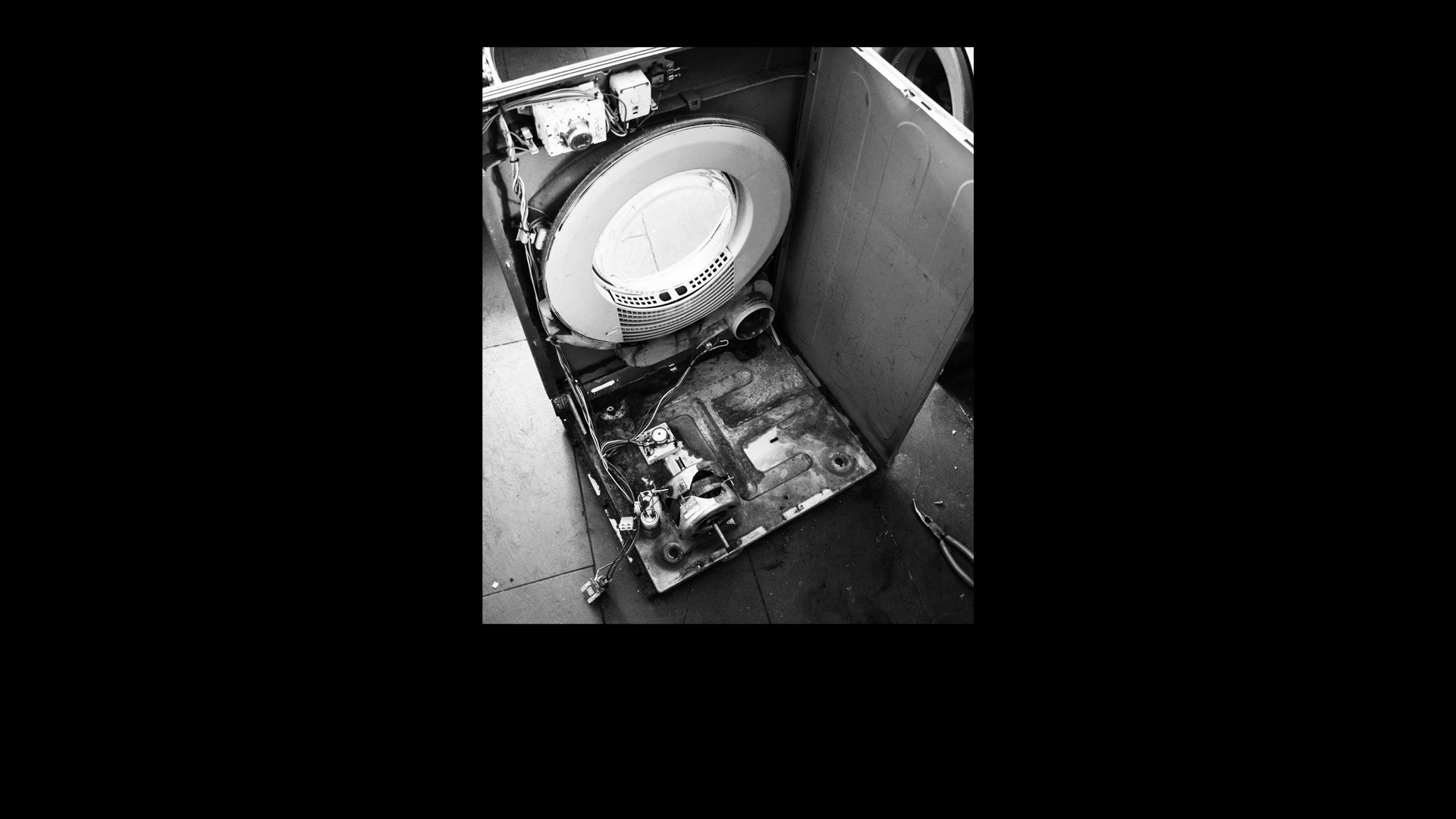

In 2014, the US-based firm bought its Italian rival Indesit, and reviewed the products now under its ownership. The company’s managers found something worrying with some models of dryers.

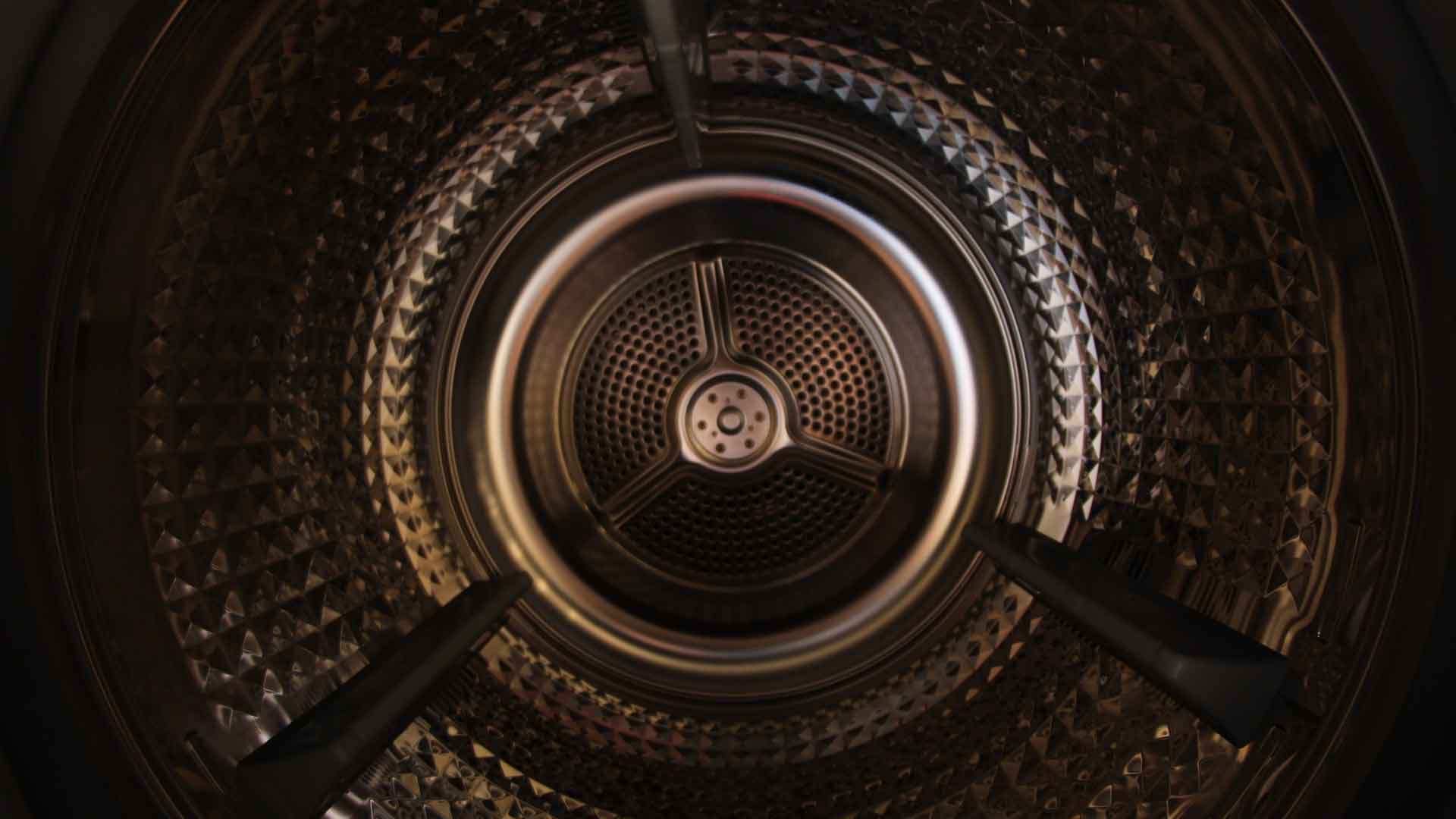

Excess fluff or lint could travel from the filter over time to the back of the machine and end up touching the heating element and causing a fire.

This design problem seemed to have existed for years.

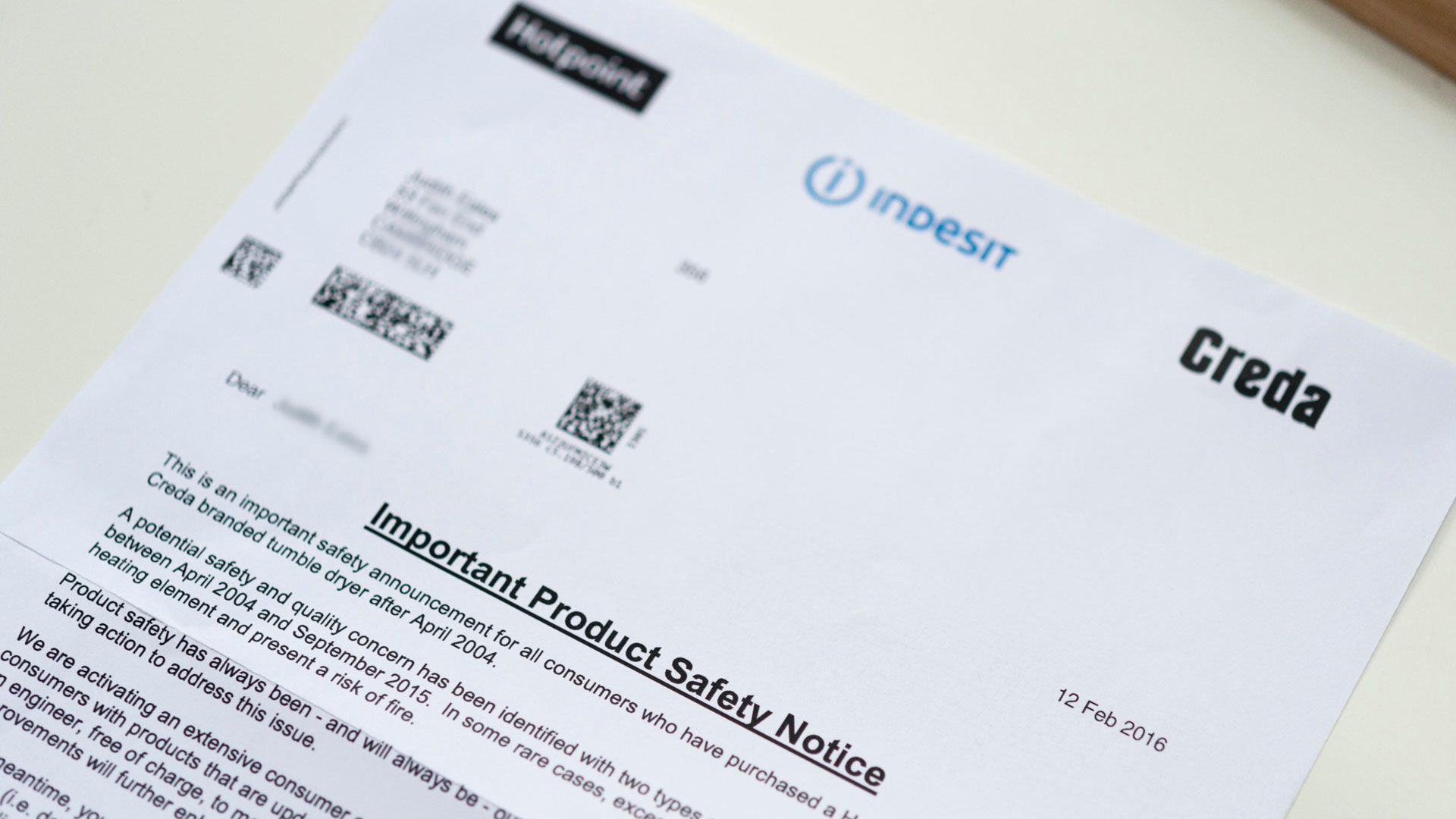

In November 2015, Whirlpool issued a notice revealing there were risks with 5.3 million dryers sold across the UK between April 2004 and September 2015.

The dryers had been made by Indesit and sold under the Hotpoint, Indesit and Creda brands. Subsequently, models under the Swan and Proline brands were added to the list. They were also found in Croatia, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia and Spain.

A full list of the affected models was never published. Instead, owners were urged to check their model on a self-service checker system.

Many welcomed the admission by Whirlpool that something needed to be done about a problem it inherited - but in the years since the company has been heavily criticised for the way it went about putting things right.

The defect in these dryers led to at least 750 fires in the UK since 2004, according to a report published by a committee of MPs in January 2018.

When Whirlpool revealed the problem, it did not immediately tell owners to stop using their dryers nor did it quickly offer refunds or new models.

Instead of a full recall, the company announced a repair programme, in agreement with trading standards officers.

Whirlpool would send a trained engineer to visit homes and modify machines by adding a widget so the fluff and the heating element never came into contact - a one-hour job.

The company sent nine million letters to four million owners, followed up with calls and messages to those who did not respond. It placed adverts and worked with landlords and consumer groups.

Whirlpool says its “unprecedented” programme has been up to six times more successful than a normal product recall, with resolutions for 1.7 million affected tumble dryers. Typically, only 10% of products in a recall are repaired or returned.

While there were 5.3 million dryers made, Whirlpool says many would have fallen out of use. In 2015, it estimated 3.8 million of them were still in use. After the modifications, and more customers replacing their dryers, it now believes that between 300,000 and 500,000 is a “conservative estimate” of how many are still being used as of June 2019.

The government has now stepped in to order Whirlpool to issue a recall of the remaining, unmodified appliances - a move that would require the company to offer refunds or replacements.

“Nothing matters more to us than people’s safety, which is why we proactively raised this product safety issue and have worked diligently and responsibly to resolve it,” a Whirlpool spokeswoman says.

But the guidance at the time of the modification scheme was controversial.

In Australia, the country’s Competition and Consumer Commission advised owners to stop using these machines in January 2016.

Crucially, in the UK, owners were initially told they could still use the dryers, as long as they were not left running when householders went out or to bed.

That advice was only changed a year later.

It was the advice being followed by the Garnham family in Guildford when their home burned down.

It was the advice being followed in August 2016 by the Defreitas family who lived in a seventh-floor flat in Shepherd's Bush in London when a fire gutted their home too.

The Defreitas family's flat in Shepherd's Bush, London, after an appliance fire

The Defreitas family's flat in Shepherd's Bush, London, after an appliance fire

Flames ripped up the side of the building - 100 families were evacuated. Many were uninsured for the loss of their belongings.

Investigations by the London Fire Brigade (LFB) found the fire started in a tumble dryer, putting Whirlpool - and its advice - under intense pressure.

The LFB - through the Local Government Association - said that owners still using these machines were “unwittingly playing Russian roulette”.

There were debates in Parliament, and consumer group Which? sought a judicial review into what it regarded as failures by the trading standards department overseeing the case - the small team at Peterborough Council.

That is one quirk of the system in the UK - in an attempt to offer consistency to businesses with multiple premises, companies deal with just one trading standards department which other local regulators must respect.

This “primary authority” system, set up in 2009, means Whirlpool - a massive corporation, with 92,000 employees, 2017 sales of $21bn, and a presence in almost every country in the world - was being checked on in the UK by a handful of officers at a financially stretched local council.

One MP described this as a “David and Goliath” relationship.

In 2016, I spent six months using Freedom of Information requests to gain access to correspondence between Whirlpool and Peterborough Council's Trading Standards department in a bid to shed some light on the deliberations between the two about the tumble dryer risks.

I was eventually sent 140 pages of correspondence, much of it redacted.

But one email reads: “...one further question from the Whirlpool side if I may - is there a way at all of possibly weaving into this sentence in any way that: 'this is not a recall campaign…”

Another calls for some agreed wording that states “this activity is correctly a REPAIR campaign and not a RECALL…”

A spokesperson for Peterborough Trading Standards said: "The initial advice that we gave was based on a risk assessment which deemed the level of risk to customers to be low.

"Our priority is the safety and protection of the public and we acted within government regulations at all times."

A committee of MPs concluded that the response of Whirlpool was “woeful”.

Their approach to correcting the defects had been “delayed and dismissive”, according to Rachel Reeves, who chairs the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee, causing “huge worry to people with these appliances in their homes”.

The U-turn on the controversial advice given alongside this campaign came in February 2017. Trading Standards ordered new guidance, namely that the dryers should not be used until they had been repaired - matching the information given to owners by authorities in Australia a year earlier.

Whirlpool suggested that owners should unplug the machine and not use it until the modification had taken place.

But there have been reports that even modified dryers were causing fires - a claim that has been vigorously challenged by the manufacturer. Whirlpool said: "There have been no reported incidents where the modification has shown to be ineffective. Recent criticisms of the effectiveness of the modification are based on fundamental technical misunderstandings of what it addresses."

The fault that the programme repaired wasn’t the only problem Whirlpool faced.

An inquest into the deaths of two men in north Wales meant the company was thrust back into the spotlight.

Sleeping danger

Bernard Hender was 19 years old when he died.

He was in bed when the fire started and smoke filled the room. His partner, funeral director Garry Lloyd Jones, tried to pull him out after being woken by the smell.

“I said 'get to the floor' because you could see the smoke was less dense on the floor,” Mr Lloyd Jones told the inquest.

“He said 'I can't find the door' and he just screamed and that was the last I heard of him.”

Bernard Hender

Bernard Hender

Doug McTavish, 39, a lodger at the flat in Llanrwst, Conwy county, also died in the fire in October 2014.

Assistant Coroner David Lewis concluded at the inquest in 2017 that the fire was caused “on the balance of probabilities” by an electrical fault with the door switch on the dryer. Forensic evidence suggested there was an issue over how the wiring was protected and whether fluff could get into the door switch.

Whirlpool had claimed the fire was caused by “spontaneous combustion” inside the tumble dryer.

Leigh Day solicitors, who represented the victims' families, said Whirlpool had brought US experts to the inquest and “at no time did they accept there was a problem”. The company did accept after the inquest that the tumble dryer was the source of the fire, but there was no admission over the specific mechanism.

There has never been a safety notice issued about that type of door switch.

The flat in Llanwrst where two men died in a 2014 house fire

The flat in Llanwrst where two men died in a 2014 house fire

The coroner identified a problem. The door switch in this case was used in hundreds of thousands of machines, and might have been a factor in a significant number of fires.

“I did not emerge from the hearing confident that Whirlpool's risk assessment processes have fully identified or appreciated the extent of the risk of fire (and its potential consequences),” he wrote in his report to prevent future deaths. The claim was denied by Whirlpool in its response to the report.

Campaigners say there is something wrong in the way we assess risk in home appliances. Manufacturers produce many thousands of units and if there are comparatively few reports of faults or fires, then the risk is deemed to be low.

But campaigners say at the first stage of a risk assessment, the number of units sold should be irrelevant.

Sian Lewis, from the Association of Manufacturers of Domestic Appliances (AMDEA) , argues that standards are always being improved and updated. Products are tested thoroughly before they are put on the market and once they are in homes.

Martyn Allen, technical director at charity Electrical Safety First, says the companies which should be applauded are those aiming to reduce the regularity of faults.

When a fire does break out, one of the greatest vulnerabilities - as the Llanrwst fire tragically exposed - is sleep.

“By the time a smoke alarm goes off, you still may not have much time - and your reaction times are slower if you are asleep,” says Deputy Assistant Commissioner Charlie Pugsley, of the London Fire Brigade.

A couple of breaths of thick, acrid smoke from burning plastic can knock out someone who already suffers from breathing difficulties.

Mr Pugsley has 23 years' service with the LFB, starting in London's East End before spending 14 years in the fire investigation team. It was one fire in Neasden, north London, in 2011, in which the risks and response “really hit home”, he says.

Muna Elmufatish, 41, her daughters Hanin Kua, 14, Basma, 13, Amal, nine, and sons Mustafa, five, and Yehya, two, died in the fire which started following a fault in a Whirlpool-branded chest freezer.

“The house had a working smoke alarm, but the fire developed so quickly,” he says.

Bassam Kua tried to save his wife and children but only he and his daughter Nur survived.

At the inquest the following year, Whirlpool said it had been unable to find a link between the freezer and the cause of the fire.

“I naively thought manufacturers would be keen to make a difference,” said Mr Pugsley. “Instead there was terrible inertia.”

The home of the Elmufatish family in Neasden, London, five of whom died in a house fire

The home of the Elmufatish family in Neasden, London, five of whom died in a house fire

Everyone accepts fires will continue to occur and risks will always remain with electrical equipment but there is pressure on manufacturers to ensure an improvement in safety.

“Companies are more than happy to take data for their own purposes,” says consumer group Which?, “so they must be able to use it for the public good.”

There is now a new code of practice for product recalls. Whirlpool says it contributed with information from its own experiences. Which? says the new code does not go far enough to get dangerous products out of the home.

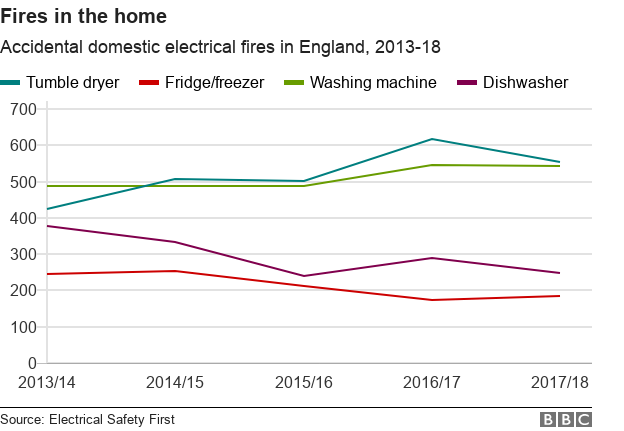

In London alone, there have been more than 300 fires which started from white goods each year for at least the past five years. That is nearly one fire a day.

The London Fire Brigade launched its Total Recalls campaign - a bid to make appliances in our homes safer.

Among the campaign’s demands are for risk assessments to recognise the threat if appliances are switched on when people are asleep, and for risk assessments to be published.

It has particular concerns over fridges and freezers that are plugged in for 24 hours a day.

Check the back

Most owners will never have looked at the back of their fridge-freezer.

There’s a layer of rigid polyurethane foam for insulation - about 5cm thick. The foam is highly flammable and, when it burns, creates dangerous gases and thick, toxic smoke.

Fire investigator Mr Pugsley describes it as almost akin to a “solid block of petrol”.

Because of the fridge-freezer’s height - usually about 1.8m - a fire starts some way above the ground and can draw in oxygen more easily.

It burns fast, the heat is extreme, so other parts of the kitchen soon reach ignition temperature and the fire quickly spreads.

That smoke can knock someone unconscious in seconds.

Evidence from firefighters suggests that the heat and poisonous emissions from a fridge would leave a typical two-storey, three-bedroom home “unable to support life within three minutes of a fire breaking out”.

The foam is covered at the back of the fridge-freezer either by metal, or by a thin plastic panel.

Both pass the same British Standards safety tests, but the speed at which a fire can develop is very different.

Tests by Which? found that no plastic-backed fridge could withstand a flame for 30 seconds, unlike every one of the metal and aluminium laminate-backed appliances that were tested. Some of the metal-backed products could withstand an open flame for five minutes.

So how could the plastic-backed fridges pass the tests? The British Standards test puts a hot wire - traditionally used in safety tests - through a sample of the fridge backing. The Which? test used an open flame instead.

“If there is a pan fire, there is a flame,” says Alex Neill, arguing that the Which? tests are more realistic.

Sian Lewis says work is going on to make testing closer to the consumer experience.

However, she points out that it must be consistent. Every test, ideally in every country, needs to work at the same level. They also need to evolve.

Firefighters called for a change in the way these products are made, but Which? went a step further. In its reviews, it has urged consumers not to buy any of the 250 plastic-backed fridges models it has listed - an unprecedented move. These include a range of brands, from AEG to Zanussi.

Other campaigners have chosen to work with manufacturers, with some success. Some have moved to manufacturing metal-backed appliances, and some online retailers have made the type of backing clearer to customers.

The campaigners say a four-sided metal box is clearly safer than a three-sided one.

The UK authorities have tried to change international standards - a benchmark for manufacturers operating across borders.

That is important because, in the UK, manufacturers could be challenged to prove their plastic-backed models are safe by trading standards officers. They cannot simply presume conformity with the official journal of standards. The law states that any products made here must be safe.

Campaigners say manufacturers dominate the committees that set the standards. They could change the rules around plastic backing tomorrow.

Five years after the LFB began its campaign there has still been no European agreement.

Appliances in the US and Canada are only metal-backed. The LFB has said that there is an injury for every 25 fires involving fridges, freezers or fridge-freezers in the US. In the UK, one in every five results in someone being hurt.

In Australia and New Zealand, the authorities have decided they cannot wait for international agreement.

In Britain, the safety of fridges is being tightened up, but campaigners want even tougher rules.

The most deadly residential fire ever in the UK is thought to have started in a fridge-freezer in a fourth-floor flat of a tower block in North Kensington.

A total of 72 people died in Grenfell Tower in June 2017 - one of the UK’s worst modern disasters.

The public inquiry has heard that the fire probably started because a tiny “crimp” connection had not kept the wires at the back of the fridge tightly gripped.

“The overheating connector in my opinion was the first event that started burning the insulation on the wires that led to a short circuit. The overheating of the crimp starts the fire. It overheats, it glows, it ignites,” John Duncan Glover, the principal engineer of Failure Electrical, told the inquiry.

The fridge-freezer - a Hotpoint FF175BP - had plastic backing.

A subsequent investigation found the appliance carried a low fire risk, but the results of the fire were catastrophic.

Tributes left to the victims of the Grenfell Tower fire

Tributes left to the victims of the Grenfell Tower fire

Whirlpool - which owns Hotpoint - argued that it was not possible to say that the fridge-freezer was the cause of the blaze. But it has been changing the manufacture of its refrigeration appliances to only use solid metal or aluminium laminate flame-retardant back panels.

Other manufacturers have made the same commitment.

And within months of the Grenfell Tower blaze, there was a new body ready to tackle product safety.

Fridge-freezer advice

- Buy a fridge-freezer, ideally metal-backed, from a reputable trader - avoiding second-hand appliances if you do not know their history

- Register it, and read the instructions booklet

- Make sure there is sufficient room behind the appliance for the air to circulate freely. Some have a bracket at the back to guide owners, and instructions should detail the space needed

- Try not to place it next to a hot appliance, such as an oven or, if possible, a dishwasher

- Ideally, avoid putting it in direct sunlight, or stuffing it too full of food, as it will have to work harder to keep the temperature down

- Do not crush the cable, and check the plug and socket for burn marks

- Defrost the freezer at least once a year in line with the instructions. Do not use a heater, hairdryer or ice pick to do so

- Check with an expert if unusual noises develop

- The appliance will eventually stop working, but should fail safely

Source: Electrical Safety First

Questions to be answered

The Office for Product Safety and Standards (OPSS) has an operating budget of £25m a year, and more than 200 staff.

Trading standards officers still police product safety out in the community but the OPSS sets the strategy.

In the summer of 2018 it published a two-year plan.

“We have a good [safety] system,” says OPSS chief executive Graham Russell. “Consumers can be confident about the safety of the products they buy.”

He does admit that the events of recent years will have “caused consumers to have concerns”. Those can be easily summed up as three questions:

Immediately after its launch, the OPSS began reviewing compliance systems at white goods manufacturers.

There is a general requirement for manufacturers, importers and distributors to ensure products are safe. But the safety standards across the board are still in effect voluntary, although some are referenced in EU law.

So, the British Standards Institution at UK level (and others at EU and global levels) are private bodies which bring manufacturers and experts together to agree what should be considered safe to sell.

Some products will develop faults over time, but a priority for the OPSS is to work out how many products are causing damage and injury and how many people are affected. Data is patchy, and so far nobody has been pulling it together and analysing it.

Campaigner Lynn Faulds Wood raised the issue in a report, saying she was surprised at how little data and information was shared. An injury database is regarded as “vital” in the US but there is nothing to compare in the UK or Europe.

Consider a small fire caused by a faulty appliance in the home.

Firefighters might put it out and not inform anyone. An insurance company might replace it and not inform anyone. A resident might throw out the dangerous appliance and have burns treated at the local walk-in clinic which does not tell anyone what caused the injury.

All three - the firefighters, the insurance company, and the NHS - have data about the incident, but it might never be pulled together. Nobody knows about the fault and the damage and injury it has caused. There is less chance of anyone stopping it happening again.

“A strategy focused on analysis and intelligence is where we can make the biggest impact,” Mr Russell says.

That intelligence must surely be helped if firefighters, for example, knew exactly which appliances had been at the centre of a fire.

The LFB's Mr Pugsley says that even after his 14 years of investigative work, it still could be impossible for him to identify a gutted appliance. Unlike the vehicle identification number in cars, there is no requirement for fireproof labelling on white goods.

Which? research suggested that of 3,203 fires in the UK thought to have been caused by faulty appliances in the year from April 2016, investigators could only find the product make and model information in 33% of cases. That is fewer than the previous three years.

The OPSS says it is researching indelible marking used in the US and elsewhere, but has yet to draw any conclusions.

Only a third of households register their appliances, according to rather limited research quoted by the OPSS.

The Register My Appliance system, introduced by AMDEA in 2015, is voluntary and covers about 90% of large white goods in the UK.

Filling in the registration form would give owners an automatic alert, usually by letter, if there is a safety issue - but many people have (unfounded) concerns they will be blitzed with spam if they register.

Whirlpool says: “Of all the lessons we have learned through our dryer campaign, the importance of product registration has been the most crucial. It is vital that consumers always register ownership of their appliances as soon as they acquire them.”

The system becomes even more difficult when items are bought second-hand. AMDEA says buyers should check the retailer, the reviews and the recalls.

There is an official recall website, but it is not searchable and not particularly user-friendly.

That means consumers are usually told about recalled faulty products via adverts, signs in shops, and the media. Typically, only 10% of recalled items are actually recalled or returned.

“Our ambition, clearly, is to get this to 100%,” says Mr Russell, from the OPSS. “It is not technology that is the barrier, it is mainly the culture.”

The evidence, he says, is from the case of Samsung's burning batteries. The Galaxy Note 7 phone was recalled after cases of overheating.

The saga is thought to have cost $5.3bn (£4.3bn) and was hugely damaging for the South Korean firm's reputation. However, from a product safety viewpoint, the recall was almost entirely successful. The company knew who owned the phones, and they were able to send updates that limited or prevented charging by anyone who kept hold of them.

That is a modern solution that may make some consumers feel uncomfortable. New technology will change the products in our homes beyond recognition - but will they be safe?

A future of 5G-connected home appliances may make things safer.

Electronic labelling might solve the problem of identification after a fire, but it still needs to work when the device has a flat battery or no screen. Artificial intelligence may prove to be more adept at spotting unsafe products than the much-criticised risk assessment system.

Internet-connected appliances may be switched on automatically, when they are needed, at any time of day. However, they can also be switched off automatically at any sign of danger.

All these questions are being asked and researched by the OPSS.

In the meantime, appliances are leading to 60 house fires a week in the UK, according to Which?.

These are fires which are destroying the wedding photographs and belongings of people like the Garnhams, are taking the young lives of people like Bernard Hender, and are the likely source of the devastation which ripped through the community in Grenfell Tower.

We must all hope the authorities come up with the answers, and soon.

Author: Kevin Peachey

Photography: Martin Eberlen

Additional photography: Getty Images, Alamy, Press Association, London Fire Brigade

Graphics: Sandra Rodriguez Chillida

Online production: Ben Milne

Editor: Finlo Rohrer