A divided flock

Election battleground: Pembrokeshire

As politicians campaign for votes, we will be looking closely at the places where the election could be won or lost. Pembrokeshire in south-west Wales, which hosts two marginal seats, has a strong sense of community but it can be a hard place for young people to make their home.

By Jon Kelly

Clare Johns strides into the field, yellow feed bucket swinging at her side, and the sheep quickly surround her like a litter of giant puppies. She has 40 of them in total, a mixture of Ryland and Shetland breeds, and Clare’s tweed coat is woven from their wool. Its colours were inspired by the Preseli Hills, the imposing range that gives its name to one of Wales’s tightest marginal seats.

Growing up in a council house, Clare had two ambitions - to be a fashion designer and to own a horse. Back then, these seemed like impossible fantasies. “We didn’t have much,” says Clare, now 35. Her mum worked as a cleaner, a lollipop lady and in the staff kitchen at the local Tesco supermarket, on top of bringing up five children on her own.

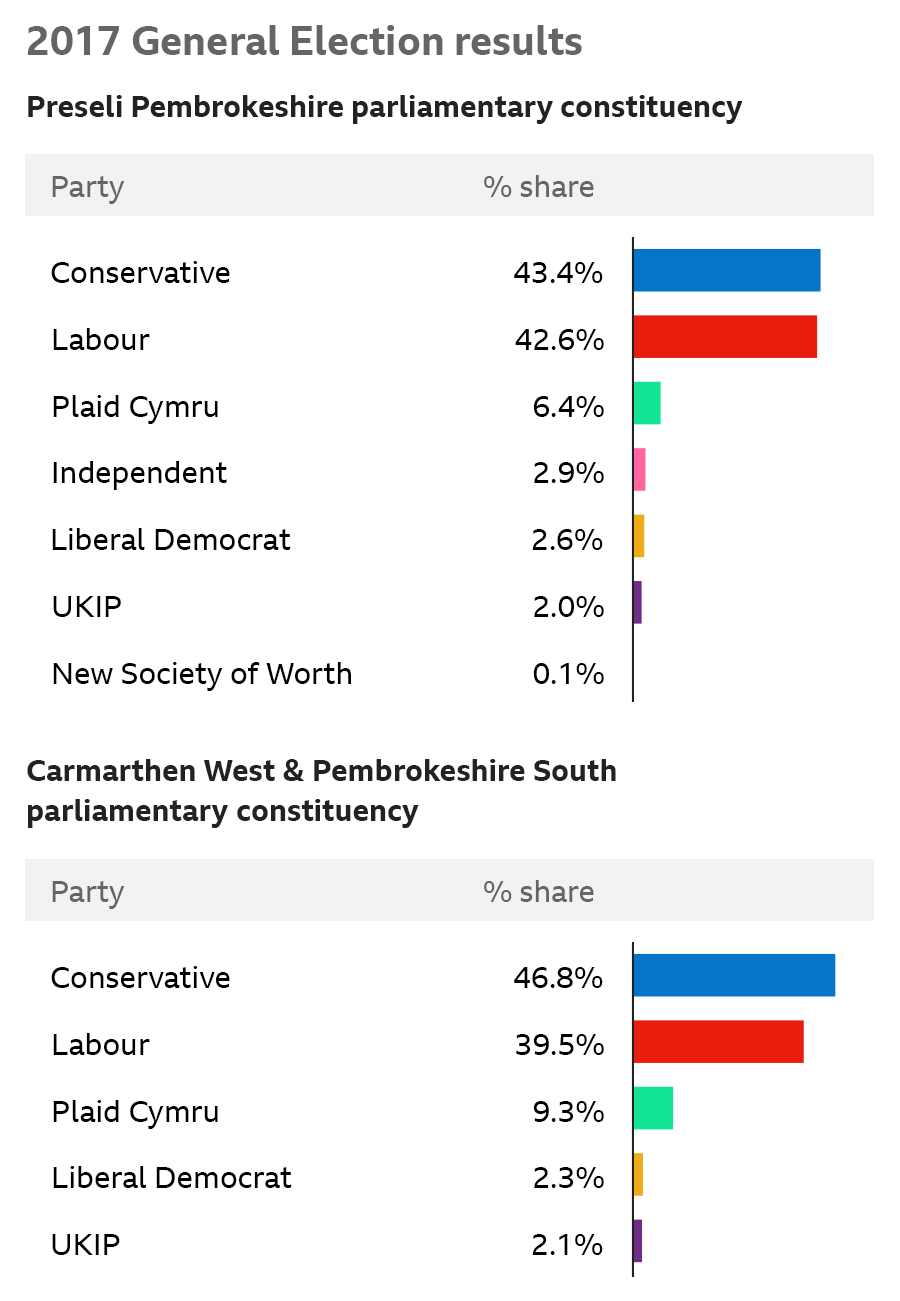

They lived in Pennar, a suburb of Pembroke Dock - now in the Carmarthen West & South Pembrokeshire constituency, held by the Conservatives by just over 3,000 votes in 2017. Across the Milford Haven waterway, you could see what is now the southernmost tip of the Preseli Pembrokeshire seat, last claimed by the Tories with a wafer-thin majority of 317 over Labour.

There wasn’t much to do in Pennar, Clare recalls. “It’s rows and rows of housing, there’s no shops.” But there were always plenty of chores to keep her occupied. The children had to light the fire, clean up, help keep the household running. It was tough but it instilled in Clare and her siblings a fierce work ethic.

Clare would watch her grandmother make clothes for the entire family on an old Singer sewing machine. It inspired Clare to do what she could with spare materials too. She didn’t enjoy school much, but a fashion textiles course at the local college changed everything. She loved being surrounded by creative people. Her tutor suggested she go to London to study for a fashion degree, but she couldn’t bring herself to do it. “As much as I love going to London, it was just too much of a jump for me,” she says. “I just felt I wasn’t confident enough to do that.”

Instead she took her fashion degree at the University of South Wales in Newport. By the time she graduated she was pregnant, and she married her husband, Owain, a few months later. It was a budget ceremony - Clare made her own wedding dress as well as dresses for her mum and the bridesmaids.

Then Clare’s husband was offered a job at a farm attached to a school in Pembroke, teaching vocational skills to children with behavioural and learning difficulties. Clare ended up teaching there too, and helping to run the farm. She was learning agricultural skills for herself - and there was the horse she’d always dreamed of. But she was also seeing a very different side of Pembrokeshire from the one on display to the four million tourists who pour in to the county each year.

Many of the teenagers the school was looking after came from deeply troubled backgrounds. Clare recalls comforting one 15-year-old boy who was crying his eyes out “because he needed his fix”. His parents were addicts too. Other pupils relied on handouts for food and clothing. Some had been lured into working for drug dealers at the age of 12.

It was against this grim backdrop that Clare took the surprising decision to launch her own luxury woollen collection.

She’d kept up her garment-making skills - working as a seamstress, doing basic repairs, making the odd bridesmaid’s dress, selling her own designs at markets. She’d tried to start her own bridalwear company “but I didn’t enjoy it - bridezillas and everything”. Then she met a weaver who suggested working with tweed. She ordered 50m and made up a small collection of her own designs - jackets, skirts, blankets. She had some angora goats on the farm so there were sweaters, too.

Clare set up a website to sell her range and offered items on a sale-or-return basis to local shops. It was quickly a success. Soon there was enough demand to start a shop in nearby Narberth with her mum and sister, and for Clare and her husband to start raising their own sheep on 12 acres of rented land.

The reality TV show Made In Chelsea ordered 50 of her jackets for its cast. The Duchess of Cornwall had one, too.

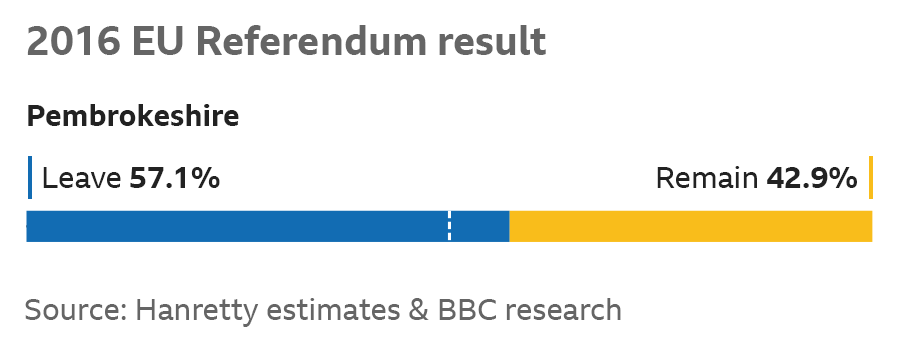

And then in 2016 the EU referendum was held. Clare voted Remain - she worried about what would happen if all the European funds currently being spent in Wales were taken away. She was angry when the result came through - both constituencies that cover Pembrokeshire voted to Leave by 55% to 45%. Wales as a whole voted for Leave by 52.5%.

Clare noticed a sudden drop in trade, which she attributes to consumers’ uncertainty about the future. “Footfall was dramatically down,” she says. “And the footfall that was coming in - they weren’t spending.” The cost of fabrics, fusing, lining, trims, pattern grading - all of it went up. She had to close the shop.

Without having to rent a retail unit, her business has recovered. But Clare thinks it took an unnecessary hit. She worries that Brexit will take years to resolve, and that will in turn mean years of further uncertainty - and in the meantime, no-one will tackle the deep-rooted rural poverty and deprivation that she saw at the school. “Because we’re in a smaller town, we get forgotten about,” she says. “Out of sight, out of mind.”

As a child, Mike Smith never thought he’d be a farmer.

Even though his father and grandfather had farmed land near Haverfordwest since 1939, he’d intended to take a different path.

As a teenager he planned to be an architect. And then, when it was time to apply to university, he started to have second thoughts. Why train for a job for seven years, only to possibly wind up unemployed at the end of it? Whereas if he worked for himself, he could do whatever he wanted.

So he went off to study agriculture instead, returning to the farm in 1996 and taking it over, with his brother, a decade ago. They have 650 acres and milk 450 cows, but it’s been a difficult era for anyone trying to make a living out of agriculture. “Pretty much for the whole time I’ve been home it’s been tough, really,” he says.

First there was BSE, then movement restrictions following the foot-and-mouth outbreak. Then in 2014 Vladimir Putin banned EU dairy products from Russia in retaliation for Western sanctions. This saw the price Mike could charge for milk drop from 30p per litre to less than 15p, taking £400,000 out of his annual turnover.

It can be a lonely business, too. While there’s a strong community of farmers, it saddens Mike how many of his old school friends have left the area - many hope to come back to retire, but he says there’s a noticeable absence of people from his generation, in their 30s to their 50s. “If you ask most of my contemporaries, if they had a choice they’d stay here, they wouldn’t have moved,” he says. “It’s a shame because you’re losing your brightest people, who should be staying and starting their own businesses and generating income within the county.”

In the 2016 referendum on EU membership, Mike voted Leave. He didn’t feel particularly fervent about it back then, but he took the view that there were opportunities as well as threats. Welsh dairy was a premium product, he reasoned, so people around the world would want to buy it - and anyway the EU hadn’t been much help when BSE had struck or Putin imposed his ban.

In the aftermath of the vote he was shocked by how rancorous the debate became. “It has split opinions between friends and family,” he says. “I see social media and look at some of my school friends’ comments - we went through the same education, how can we think so differently?”

Some told him he was stupid to have voted Leave, given the payments from Brussels that farmers receive. Mike doesn’t see it that way. “To be honest the subsidies from Europe I see more as a big stick that they use to beat us with,” he says. “It’s just the next set of hoops that the government want us to jump through for less and less money.”

Over the last three years Mike’s opinion about Brexit has hardened, principally because of the manner in which Parliament has conducted itself. “I think it’s a disgrace the way it’s been handled,” he says. He suspects there’s been an effort by Remainer MPs to drag things out as long as possible so that everyone gets sick of it.

He’d rather Brexit was over and done with so that the government could get on with the things he says really matter, like the NHS and jobs. But there’s a point of consensus with Clare. Like her, Mike says the county’s remoteness allows it to be ignored by those in power. “I’d say Pembrokeshire is so far out on a limb I think it just gets forgotten about, full stop.”

At the foot of the Preseli hills is a small village called Maenclochog. It has a post office, a church, a general store, and two garages. There’s an art gallery and a school where lessons are taught in Welsh - if you visit the cafe or the pub, it’s likely you’ll hear the language spoken there too. And everyone will know who you’re talking about if you ask after Meg Cakes.

That’s the nickname Megan Davies is known by. Megan is 25 and runs her own cake-baking business from her kitchen, in the village where she’s lived most of her life. “I can’t imagine my life anywhere else than here,” she says. “If I go down the shop, my auntie works there - I definitely will see someone I know. I think that’s what I missed when I lived in Cardiff.”

After school, Megan moved to the Welsh capital to study graphic design. She’d visited before, but the scale and size of the place meant being there full-time was quite a radical change for her. She made lots of friends and it was a novelty being able to pop across the road to the shops, instead of driving for 20 minutes to the nearest town. But when she was on her way home at night from anywhere in Cardiff she’d ring her mum and dad, because it made her feel safer.

Although she liked it there, ultimately the course wasn’t right for her. After two years she dropped out and moved back to live with her parents in Maenclochog. She didn’t have much to do there at first apart from go on Facebook and upload pictures of cupcakes she’d baked. A friend asked her to make a cake for her boyfriend; he was a builder, so Megan baked one with a little fondant icing construction worker on top, next to a pile of fondant icing bricks.

It was fairly rudimentary by her later standards, but Megan was pleased with it. She posted a photo online, and more and more people started asking her to bake a cake for them, too - wedding cakes, birthday cakes, cakes with Disney heroines on top of them, or the logos of football teams, or Elvis.

Word of mouth helped her build her business in a way that would never have been possible in a less tightly knitted environment - if you needed something baked for a special occasion, you’d ask around and someone would tell you about Meg Cakes. But social media - Instagram and Facebook in particular - was a peculiarly modern and effective way of promoting a rural business. When Megan posts a photo, 100 people might see it within 10 minutes. “You’re not going to have 100 people passing your shopfront in a place like this,” she says.

Much as she loves Maenclochog, she knows it has its downsides. There’s only one bus service, to Haverfordwest. “Just one. That’s it,” she says. “I think it’s gone for five hours and then you’ve got to come back.” Friends who grew up in the village can find jobs readily enough if they train as a teacher or a nurse. But Megan’s older sister, who has a degree in fine art, had to move to Bristol in search of employment. She’d like to return one day.

Battlegrounds

Support for the Welsh language is important to Megan, too. “I know this is going to sound silly now, but until I went to university, I never really realised that I spoke two languages,” she says. She’d absorbed both as a child and it always felt natural to switch between the two. She’d like her own children to speak the language, but she worries it’s dying out.

For a while she worked in a pub a few miles away called the Tafarn Sinc, where Welsh is spoken at the bar. The community rallied round to save it when it was at risk of closure, and she appreciates living in a place where people make an effort, however small, to keep Welsh alive. “It’s good when you go places, even if it’s just ‘Welcome and croeso’ - it’s something, isn’t it?”

Community spirit notwithstanding, Megan steers away from talking about Brexit around the village. “I think around here people had made their mind up and they were totally for Leave or Remain,” she says. “You don’t want to ask people because you don’t want a lecture about it.”

In 2016 she made sure to read up on the arguments for and against but ultimately didn’t feel well informed enough to adopt a strong set of opinions on the subject. “I know that might sound really bad but I didn’t know what to do,” she says. “So I just thought: ‘My life’s fine now, I’ll vote Remain.’”

For now, her business hasn’t been affected by the Brexit vote, though she says some have. Through her work around weddings, she heard of a florist's that can’t take advance bookings because it can’t rely on the price of imported flowers staying the same in the event of a no-deal exit from the EU.

For Megan the bigger issue is the uncertainty, not the relentless verbal war of attrition. She finds herself wondering what would happen if Brexit were somehow resolved, one way or the other. “What would they talk about on the news? It’s just everywhere - Brexit, Brexit, Brexit. The word’s getting on my nerves.”

It’s a cold winter day and David Annis is looking ruefully at his market stall. Sales have plummeted since the end of the tourist season. “We’re struggling to get people to come because now that the visitors have gone it’s only locals who are left,” he says. And the locals aren’t buying.

On Fridays, David, 69, sets up for business in Haverfordwest; on Saturdays, he’s in Fishguard, the coastal town at the northern end of Pembrokeshire, close to his home. Half of his stall is given over to handmade wooden crafts, glasswear, textiles. The other half is baked goods made by his wife - cakes, pies, fancies and so on.

“Most of Fishguard’s regulars are older people at this time of year and if you have a day like today they’re not going to come out in this wind,” he says. “So it’s a struggle, really.”

In the summer it’s a different story. Fishguard is linked by ferry with Rosslare in the Republic of Ireland. One day earlier this year, when a cruise ship disembarked, local people formed a welcoming committee, with stalls and music.

While Clare, Mike and Megan were all born in Pembrokeshire, David made it his home. He’d been living in Essex and working in London, but an epileptic fit while he was driving 35 years ago put an end to his career. Charity work and the market stall have kept him occupied ever since.

In 2016, David voted Leave. To him, the EU represented bureaucracy and snouts in the trough – unelected people “telling us what to do and filling their pockets”.

Like Mike, he’s annoyed that Parliament has failed to carry out the instructions given by the electorate during the referendum. His family hosts African students who come to Wales to learn about agriculture, and it embarrasses him when these young people see British MPs acting like “a nursery class”, shouting at each other rather than getting on with the job.

But since the prime minister returned with his latest Brexit deal - which effectively creates a customs border between Great Britain and the island of Ireland - David has started to worry what it will mean for Fishguard.

The area enjoys strong cultural links with the Irish Republic. Each year, he takes his market stall to the Wexford Food Festival. He doesn’t make much money but it’s good PR for Pembrokeshire.

“I am now more worried about it - about going out,” he says. “One of our few remaining industries is that ferry. Are the things we get from there going to be more expensive? Is it going to be harder to export things to there because of charges they’ll make for imports? We don’t know.”

It doesn’t look to him like the government has handled the entire process well. There doesn’t seem to him to be anyone at the top with the wherewithal to make a go of it.

But he’s still sure Brexit needs to happen.

“The main thing is, the majority voted to leave the EU in 2016,” he says. “It’s now 2019 and we thought democracy was the rule of the majority. If they don’t listen to the majority then so many people are going to say: ‘Why bother voting?’”

Outside, despite the bad weather, the ferry is leaving Fishguard for Rosslare on schedule. The wind howls around it, and the seas are choppy, but the vessel keeps inching ahead, upright, towards its destination.

For a full list of general election 2019 candidates standing in Preseli Pembrokeshire and Carmarthen West and South Pembrokeshire see our pages below:

Preseli Pembrokeshire parliamentary constituency

Carmarthen West & South Pembrokeshire parliamentary constituency

Credits

Author: Jon Kelly

Online Producer: James Percy

Researcher: Catherine Evans

Graphic Designers: Irene de la Torre Arenas and Sean Willmott

Photographer: Aled Llywelyn

Photo Editor: Phil Coomes

Editor: Stephen Mulvey

More from BBC News

Preseli Pembrokeshire parliamentary constituency

Carmarthen West & South Pembrokeshire parliamentary constituency