14:30 in Rio. The story of a death

By Hugo Bachega

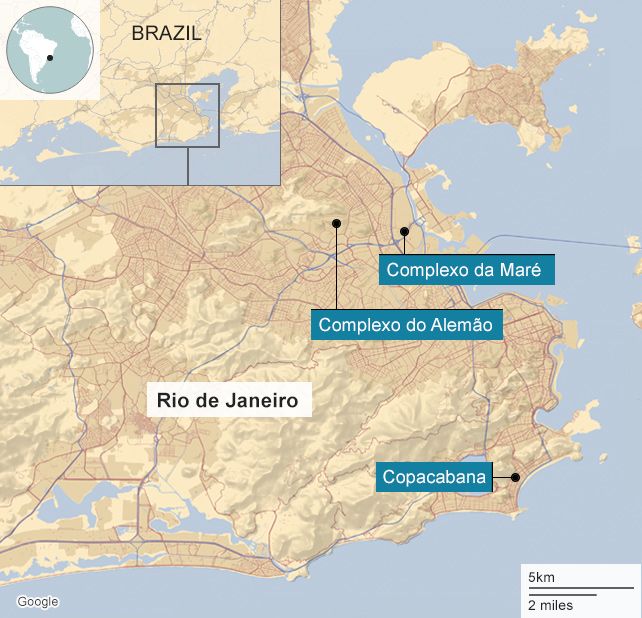

It was about 14:30 on 14 May when Jean Rodrigo da Silva Aldrovande pulled up on Carmen Cintra, a street in a poor district in northern Rio de Janeiro. Few in Alemão actually know Carmen Cintra by its name. Many call it Rua Do Rio, or River Street, because of the polluted stream that runs there, dividing it in two.

It was an ordinary day for Jean Rodrigo. The popular Brazilian jiu-jitsu teacher was about to give a class to youngsters at a social project, just as he had been doing for years. He arrived with his eldest son, Juan, and a student, Thiago.

Jean Rodrigo parked in his usual spot near the stream and as Juan, 17, went inside to get himself ready, Thiago, 18, waited to help him take in some boxes. It was a warm winter day and Jean Rodrigo was shirtless, having yet to change into his kimono. He was in good spirits. Hours earlier, his martial arts “master” had invited him to referee at a competition, an unexpected honour for a brown belt.

Jean Rodrigo with his wife, Andrea

Jean Rodrigo with his wife, Andrea

The normally busy street was quiet, and as teacher and student unloaded the car, a police vehicle arrived. Four officers rushed out and positioned themselves on the same side of the street as Jean Rodrigo and Thiago. On the other side of the street, Thiago saw a boy with a rifle. It all happened very quickly. There was no time to run.

Having lived most of his life in Alemão, Jean Rodrigo probably knew what was going to happen. Thiago said he had shouted to him “Get down! Get down!” As they both sought cover beside Jean Rodrigo’s car and another parked behind it, the shots came fast.

When Thiago realised he had been injured in the leg, he desperately called out to Jean Rodrigo for help: “Teacher, teacher.” But there was no reply.

Shot in the head, Jean Rodrigo died instantly with the car keys still in his hand.

By the time his wife Andrea Rios arrived at the scene some two hours later, Jean Rodrigo’s body had been covered by a blanket. A group had gathered around it, and there they stayed in a circle into the late evening.

Jean Rodrigo had discovered jiu-jitsu almost by accident. When he was young, he had worked as a cleaner at a small gym, and every day after work he would quietly sit by the mat to watch the martial arts classes he could not afford. Over time, he picked up a few moves, saved some money to be properly coached, and eventually became a teacher himself.

His family paint a portrait of a well-liked man who offered help in the gym and outside, with words of advice. He had no involvement with gangs, they say, nor had he ever been arrested. “Samurai”, as he was known, often told the students - and his four children - that jiu-jitsu could take them “from Alemão to the world”.

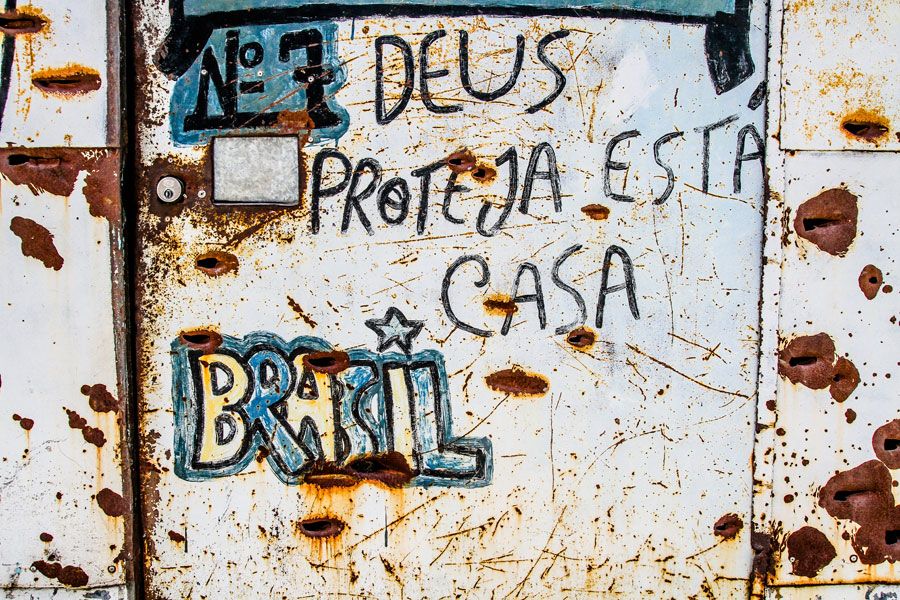

He knew that for many of them, it could be very much either this or falling into a life of crime. It is easy to see why. The graffiti on the houses in Alemão celebrate the powerful group of drug traffickers Red Command, or Comando Vermelho, leaving no doubt about who is the authority here.

Jean Rodrigo (sitting, centre) with fellow jiu jitsu enthusiasts

Jean Rodrigo (sitting, centre) with fellow jiu jitsu enthusiasts

I meet Andrea for the first time six weeks after Jean Rodrigo’s death, a day after he would have turned 40. The couple had got together on Brazil’s Valentine’s Day - 12 June - in 2018, and had quickly become “like husband and wife”, she says. The house they had shared, not far from Alemão, belonged to Andrea’s grandmother. It was so small that the living room was the only place they could put the fridge. On it was an old magnet that read: Peace.

“Everybody knows it’s a violent area, and that’s why Jean Rodrigo wanted the project there,” Andrea says. “It was the only opportunity these children have.” He was a reference point for many of them, she says, and some called him late at night or at weekends, "sometimes crying”, looking for guidance.

Maneco Team, the martial arts project, had some nine students when Jean Rodrigo started it in 2012; seven years later, there were about 90. The club mainly relied on donations, scarce at the best of times. Classes were held in a room with high walls and peeling paint. Often students would get water from the taxi stand across the street because they could not get their ageing drinking fountain fixed. Kimonos were handed down when they had been grown out of, or someone had scraped the money together for a new one.

Jean Rodrigo, Andrea says, had warned her right from the start that his life was all about Brazilian jiu-jitsu. This type of martial art, based on taking the fight to the ground, is now popular around the world and earlier this year a friend offered Jean Rodrigo the chance to do some coaching in Abu Dhabi. But he turned it down. “Who was he going to help there? People need help here,” Andrea says. “He said: ‘My place is here, in Brazil, at Alemão.’”

The Maneco Team received funding from the federal government, just enough to pay Jean Rodrigo 950 reais ($250; £200) a month. It was not a lot, but he still used some of it to cover the fees for his students at competitions. Jean Rodrigo himself competed and, in April, won a bronze medal at a regional championship. He was getting ready for two bigger tournaments in May, including a national competition.

His main income came from delivering gas bottles with his father early in the morning. There were times when he could not pay for either petrol for his car or the bus ticket to go to the lessons. So he would go by foot, and that meant walking for well over an hour under a sun that spares no-one. “He lived for this,” says Diego, his brother.

On the day of his death, Jean Rodrigo had spent a rare morning with his wife at home. He was “euphoric” after the phone call asking him to be a referee, says Andrea. “He was joking, making hand gestures referees usually do, saying to me: ‘You’ve been penalised!’ It was his dream.”

How Jean Rodrigo was killed is not yet completely clear, but Andrea is certain that he was shot by the police. “You think a lot of things. Was it because he was black? At the entrance to a favela? Was he mistaken for someone else? They could have asked for his ID. He was a law-abiding citizen. Why did they shoot him?”

In an account of the events Thiago sent to the family on WhatsApp, he says he and Jean Rodrigo lay on the ground next to the car. “I don’t know whether the police positioned their rifle under the car... and shot [at us] thinking we were criminals. I heard a lot of shots. They fired under the car [towards] where we were.”

Diego was one of the first to arrive at the scene. There, he says, he found four empty rifle bullet casings where the officers had positioned themselves, 3-5m (10-16ft) from where Jean Rodrigo and Thiago had hidden. There were bullet marks in the gutter near where they had been crouching, he adds.

When Juan came out of the gym and saw his father’s motionless body on the ground, he shouted to the policemen “You’ve shot a resident, you’ve shot a resident,” Diego says, but the officers got back in their car and left.

As word spread in Alemão that their coach had been killed, the impromptu gathering around Jean Rodrigo’s body grew into a protest against what was seen as another police killing.

There are hundreds of favelas in Rio, possibly even 1,000. Experts say decades of state neglect have allowed gangs to flourish, and in many of them they are the de facto rulers. The police presence is so weak that when they do come, it is often to conduct operations. Gun battles are almost the norm. For a long time Alemão, a maze of more than a dozen slums built on hill slopes, was considered one of the city’s most dangerous.

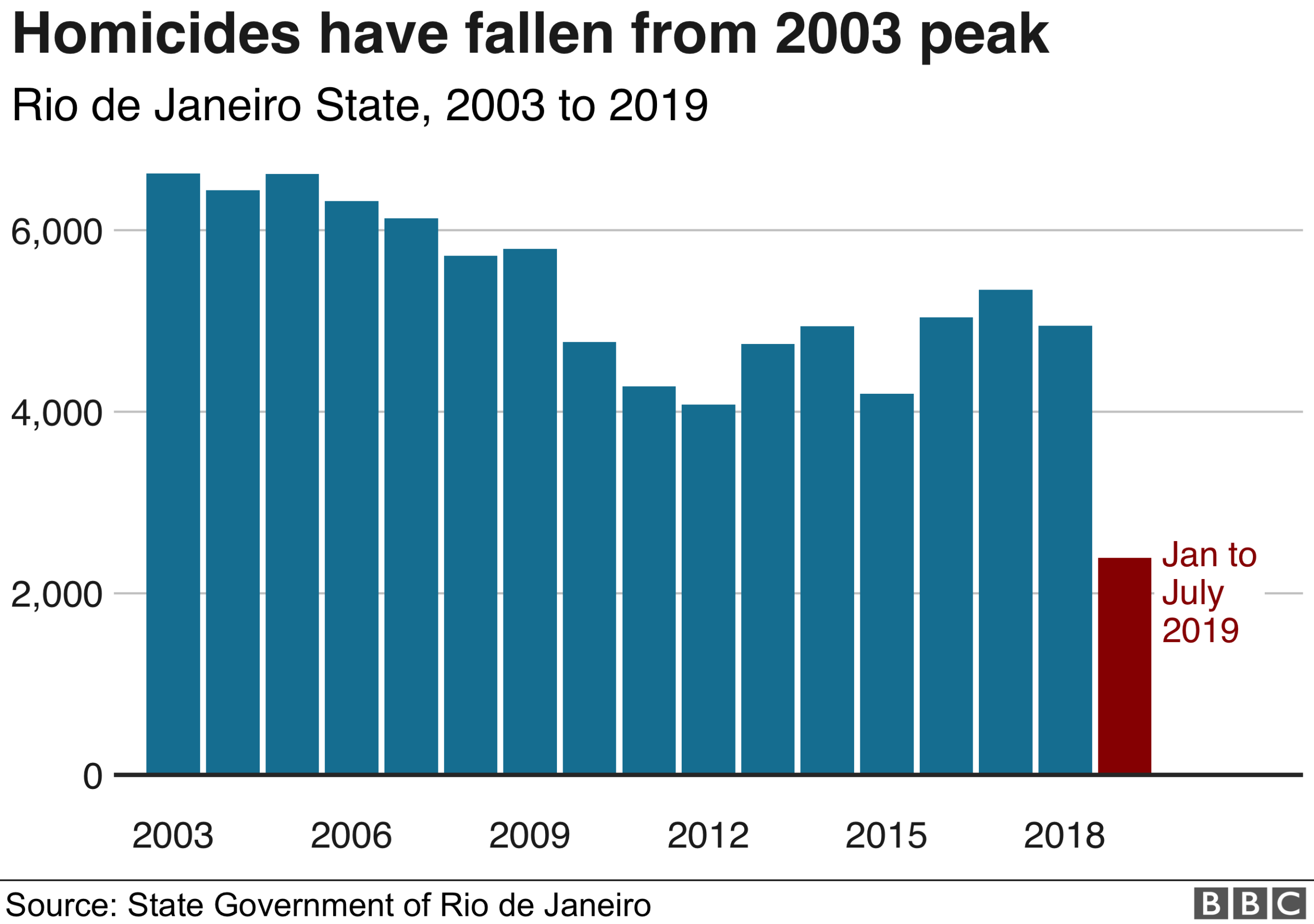

Ten years or so ago, before Rio hosted the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympic Games, there was hope that things could finally change as government programmes brought much-needed policing and social services to some areas, leading to a drop in crime.

But money for these projects practically ended as recession took hold in Brazil in 2014. Violence spiked, and the federal government temporarily intervened last year. In an unprecedented decision, the army was put in charge of security. While there was a reduction in some types of crime, critics still question whether it has had any long-term impact.

Last October, Wilson Witzel, a 51-year-old conservative former judge and marine, was elected governor of Rio de Janeiro state, promising to be tough on crime. During his campaign, he said the authorities would “dig graves” to bury criminals if necessary.

Days after being elected, he vowed to “slaughter” anyone caught carrying a rifle. “The police will do the right thing,” he told a newspaper, “aim at their little heads and fire! So there’s no mistake.” Legal experts argue that shooting at people is unlawful if officers are not acting in self-defence.

Witzel has an ally in Brazil’s far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, a former army captain and congressman for Rio, who also took office in January. They agree on many things, including that officers should not face charges if they kill on duty. “A policeman who doesn’t kill,” Bolsonaro once said, “isn’t a policeman.”

Wilson Witzel and President Jair Bolsonaro

Wilson Witzel and President Jair Bolsonaro

Bolsonaro, whose trademark gesture is a weapon with his thumb and index finger, has also worked to ease citizens’ access to guns so, he says, they will be able to defend themselves.

Under Witzel’s watch, police raids in the greater Rio area increased 42% between March and June, according to a study by Rede de Observatórios de Segurança, or Security Observatory Network, a national group of researchers. The raids often take place in densely populated favelas, with large numbers of officers, heavy weapons, armoured vehicles and even helicopters with snipers.

While I was in Rio, I downloaded the app Fogo Cruzado (Crossfire) which monitors operations and shootings and is frequently used by residents to avoid risky areas. I was alarmed by how frequent these raids were.

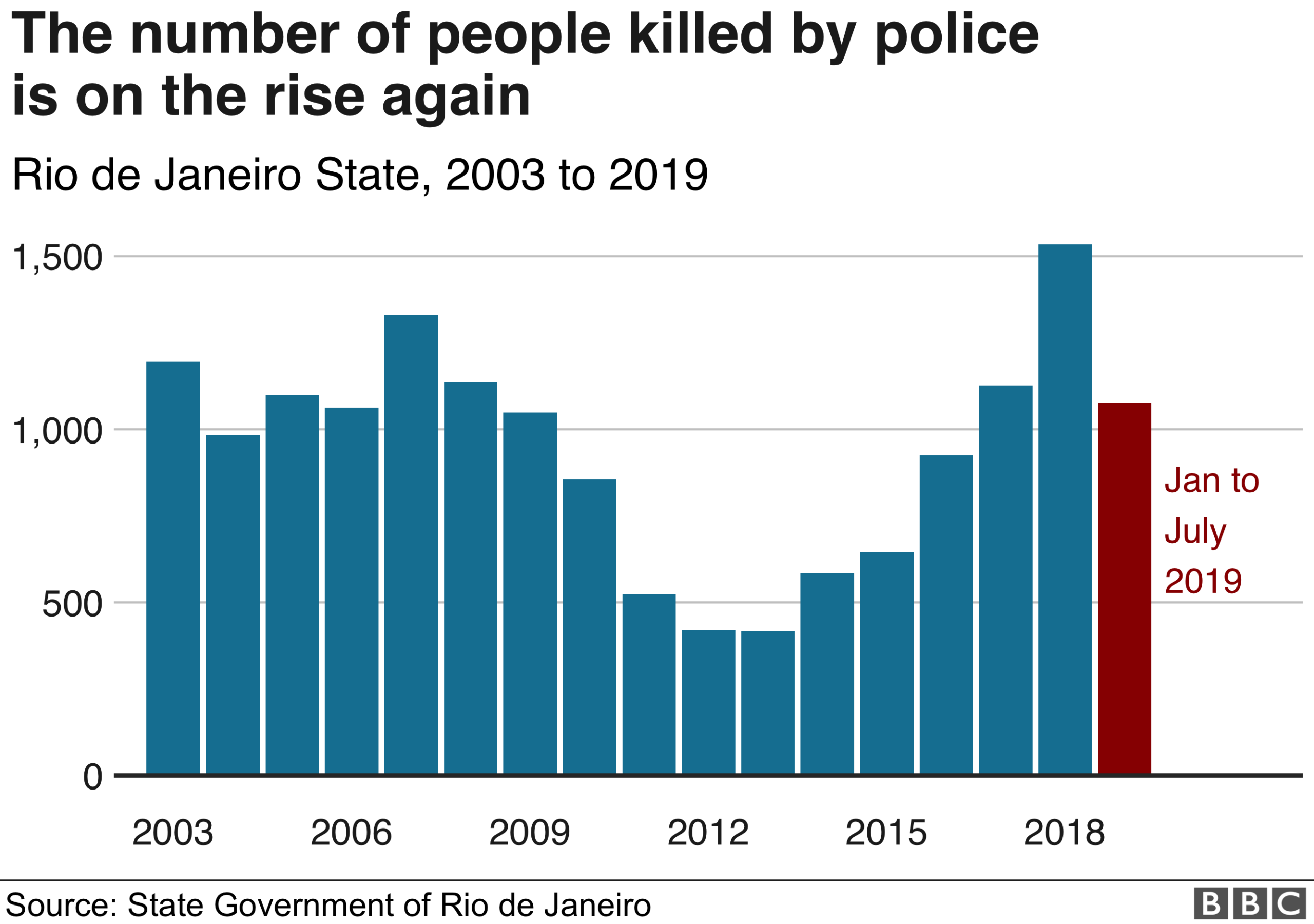

Between January and July, police operations resulted in 1,075 deaths, an average of five per day, the highest number since official records began 20 years ago. Most of those who die are male, black and young. And while many are suspected criminals who have died in confrontations, there is also an unknown number of unarmed people and bystanders among the victims.

“Both the state and federal governments are openly encouraging the killings of people,” says Dr Ignacio Cano, a professor of sociology at the State University of Rio (UERJ), and one of Brazil’s leading experts on violence. “In the past it was a more masked, subtler incentive. Today, it has become official policy.”

In June, a television programme showed several armed men walking freely in Cidade de Deus, the favela in western Rio made famous by the movie City of God. All the while, children in uniform appeared to be making their way to school.

“In other parts of the world,” Witzel said, referring to the images during a speech to announce the expansion of a security programme, “we’d be allowed to send a missile to blow those [suspects] up.” He was applauded.

While most of the battles between police and heavily-armed criminals have taken place on the streets of the favelas, Witzel, who had no previous political experience before becoming governor, has not hidden his enthusiasm for putting police marksmen in the sky. In May, he posted a video of himself on Twitter aboard a helicopter next to a sniper saying: “We’ll put an end to banditry... It’s over!”

Snipers on police helicopters - popularly called “caveirão voador”, or “flying big skull” after the name for armoured police vehicles, “caveirão” - opened fire in 11 operations in the first six months of this year across Rio, according to Fogo Cruzado.

Wilson Witzel

Wilson Witzel

One morning in Maré, Rio’s largest favela complex, Douglas Oliveira was working at the local library overseeing some children when he heard the sound of fireworks, the usual warning given by criminals that the police were about to launch a raid. As he left the building with a young girl, he saw a police helicopter with a sniper.

“It shot in my direction. They didn’t care,” Oliveira, 24, says. “I started to pray. I thought about running.” But if he had run, he says, he thought he could have been mistaken for a suspect and become a direct target. So he kept walking, terrified, until he finally arrived at a nearby community activist office.

A non-profit group based in the same favela, Redes da Maré, posted a video showing at least 19 bullet marks on the ground, which had allegedly been caused by a sniper on board a police helicopter in May. After the operation, the director of a school in the area posted pictures of a huge sign she had put on its roof two years ago, reading: “School. Don’t shoot.”

Snipers, Witzel said, had also been deployed on the ground in undisclosed locations across the state. When asked by a newspaper about how many people had been shot dead, he said he had “no idea” because it was not his job to keep a tally of who was being killed by the police.

Following Witzel’s video on the helicopter, Renata Souza, an opposition state parliamentarian, called on the United Nations to investigate the operations, saying the governor was personally leading a “policy of massacre”. She had already made a similar request to the Organization of American States.

Renata Souza

Renata Souza

“We don’t have the death penalty,” Souza, who also heads the Human Rights Commission at Rio State Assembly, tells me, “but Witzel is making this the policy in favelas and suburbs.” A month later, federal prosecutors said officers who had opened fire from helicopters would be investigated for possible crimes.

At the protest next to Jean Rodrigo’s body after his death, friends took turns to pay emotional tributes. “We won’t forget the things he did,” one man told the crowd, “we need to keep [him] in our hearts.” Another said: “We have to continue what he started.”

By the evening, journalists had gathered at the scene. Jean Rodrigo’s mother Sandra gave an emotional interview, saying: “When will [Witzel’s] police stop killing our sons? Ask Witzel. When will the police stop killing workers? Fathers?”

Witzel himself described Jean Rodrigo’s death as “sad”. “It won’t end in impunity… Those found responsible will be tried in the courts,” he wrote on Twitter a day later. The governor’s words were “beautiful”, says Andrea, but not enough. “Nothing will bring [Jean Rodrigo] back, but at the least it can’t remain unsolved.” The police, she says, have not yet told her anything about what happened that day.

Rio’s military police department said in an email to the BBC that four military officers who were in a patrol car had come under fire near the Carmen Cintra street by two armed men on two motorbikes. After a gunfight, they returned to the police station, unaware that people had been hit.

But investigating cases involving the police is not easy. Paulo Roberto Mello Cunha, a state prosecutor, leads a team that looks into allegations of police violence, but mostly there is not a lot it can do. “You have to count on the police to investigate the police,” he says. “I don’t do forensics, for example.”

States in Brazil have two separate police forces - the military force in charge of public order, and the civil force to carry out forensics and investigations.

Apart from the chronic lack of personnel and resources, Cunha’s team often struggles with inadequate evidence from crime scenes that have not been preserved, sometimes intentionally.

There are frequent claims from relatives and activists of people being taken to hospital already dead in alleged attempts by officers to cover up possible wrongdoing, or even of guns and drugs being put next to victims’ bodies as ways to incriminate them.

I was told that residents and Jean Rodrigo’s relatives had gathered next to his body to protect the area until the forensics team arrived. His family also quickly released his pay cheque from the federal government and his jiu-jitsu certificates, hoping it would demonstrate that he was a working man with no links with criminals.

Often, fearful witnesses remain silent and prosecutors reject taking on investigations, aware that they could become targets. Cunha himself has been given bodyguards after he and his family received threats. “We rarely have a proper investigation,” he says. “Sometimes it works. Depending on the stars, it’ll work. But that’s not the rule.”

Since 2016, when his group was set up, they have investigated some 1,300 cases. Charges have been pressed in less than 5% of them. “Before, we had 0% of the cases, so I think we’re building something,” he says. “The bar is pretty low.”

“I won’t backtrack,” Witzel said in August, arguing his government was “in the right way”. Proof of this, he said, was the drop in homicides - there were 2,392 cases in the state between January and July, a drop of 23% from 2018. Violent thefts and robberies are also falling, while the police have seized large amounts of drugs and weapons.

The Red Command - Rio’s largest drug gang, controlling a vast number of neighbourhoods - was even running out of ammunition, Witzel claimed. He also said that drug traffickers should be legally defined as terrorists, with harsher sentences. “You can’t combat terrorism with flowers,” he said last month. “The message has been sent: Don’t fight the police.”

It is not yet clear whether the improvements celebrated by Witzel are a direct result of his policies, experts say. The fall in the homicide rate, in particular, appears to follow a national trend - official numbers suggest 6,543 cases nationwide between January and February, a 20% drop on the same time last year.

While Witzel has focused on drug traffickers, critics say he has downplayed the threat from violent paramilitary groups created by policemen, active and retired, known as milícias. None of the deaths in police operations between January and June occurred in districts where they are active, according to UOL Notícias, a news website.

Witzel’s office did not respond to requests for an interview.

Outside Rio’s poorest districts, there is some support for Witzel’s policies, as frightened residents despair of seeing an end to the violence. “We have to kill those boys,” one resident of Barra da Tijuca, a fashionable seaside neighbourhood where President Bolsonaro has a private residence, tells me, referring to drug traffickers. When I say innocent people are also being killed, he replies: “It’s the price!”

The police were responsible for almost a third of all violent deaths - essentially any death that is not accidental or natural - in Rio de Janeiro between January and July, according to the state’s Institute for Public Safety.

Parliamentarian Renata Souza says there is “widespread fear” that extrajudicial executions are being carried out. “There are operations in which the killings are indiscriminate... These are massacres committed by the state.”

In February, residents of Fallet-Fogueteiro in the centre of Rio said nine men were tortured and stabbed by officers in a house, killed even after they had surrendered. Police said the suspects had responded with gunfire when they arrived, and the residence reportedly had 182 bullet holes on it.

Locals, however, said the police had surrounded the place and that there had been no gunfight. In total, 15 people were killed, the deadliest raid in Rio in 12 years. Witzel defended the operation as “legitimate”.

In May’s operation with the helicopter in Maré, police said they were looking for a suspected drug lord. Pictures of pupils fleeing a school as the police hovered overhead went viral. Eight people were killed in the raid, four of them in a single house.

Again, residents said the men had already surrendered when they were killed. A witness, whose house was broken into by the heavily armed suspected drug traffickers, told me on condition of anonymity: “One of [the suspects] said ‘Perdi’, ‘I’ve lost it.’ The policeman said: ‘You didn’t only lose. My order is to kill.’”

Both cases are still being investigated by the police. But Jurema Werneck, executive director of Amnesty International Brasil, says authorities are allowing this “violent approach” by officers.

“Killing people can’t be considered public policy,” Werneck, who was herself born in a favela, says. “We have the proper way to deal with [suspected criminals]. It has to be in front of justice and not in front of guns.”

A number of operations have drawn comparisons with some of the policies Rodrigo Duterte, the president of the Philippines, has implemented in his own war on drugs. Some 6,600 people have been killed there since 2016, according to police, but activists put this number at 27,000.

Witzel, however, rejects the accusation that officers shoot indiscriminately. “The police,” he said in May, “don’t kill innocents.”

The military police department says its operations are based on “prior planning and executed within the law” and that “criminals are the ones who typically initiate confrontation”.

Col Carlos Fernando Ferreira Belo, president of Rio’s Military Police Officers Federation, the group that represents officers, says operations are usually “very intense and stressful” for the police. As a rule, he says, officers are attacked by criminals and that they “have to respond in the same proportion”.

In the first six months of the year, seven policemen were killed while on duty in Rio. “The fact that in the confrontations criminals die I’d say ‘Thanks God!’ and I applaud it,” says Belo. “Killing is not the mission of the military police, but dying even less so.”

Over four days in January, two men were shot dead in the northern neighbourhood of Manguinhos, with residents blaming snipers based in a tower at the civil police headquarters nearby. The cases are being investigated by the police and Cunha’s team, but a post-mortem examination published by Extra newspaper said one of them had been killed by a bullet fired from above. There was no suggestion any of them were armed.

After six people aged between 16 and 21 were killed in police operations in five days this month, Meia Hora, a local tabloid, printed bullet marks on its front page with the headline: “In Rio, killing is a game.”

On the locked gate to the building where Jean Rodrigo used to hold his jiu-jitsu classes is a sign saying the team has moved. “Some children no longer felt safe there,” says Marcos Vinicius, one of Jean Rodrigo’s friends who now helps with the lessons. Others simply did not want to go back to their old place. They felt Jean Rodrigo everywhere.

Andrea has moved, because she too felt his presence in the home they shared. “The joy I had,” she says, “is over.”

When Jean Rodrigo was buried, two days after he was killed, his students wore kimonos and brought the medals they had won in competitions. They launched white balloons in the air asking for peace, and applauded when the jiu-jitsu “master” posthumously gave Jean Rodrigo a black belt.

Listen to Assignment, Lethal Force in Rio's Favelas, on the BBC World Service and BBC Sounds

Credits

Author: Hugo Bachega

Producer: James Percy

Editor: Kathryn Westcott

Graphics: Paul Hastie

Photos: Bruno Itan, Reuters, Getty, Alamy

More Long Reads

Jair Bolsonaro - Brazil’s unlikely president

The girl who was never meant to survive

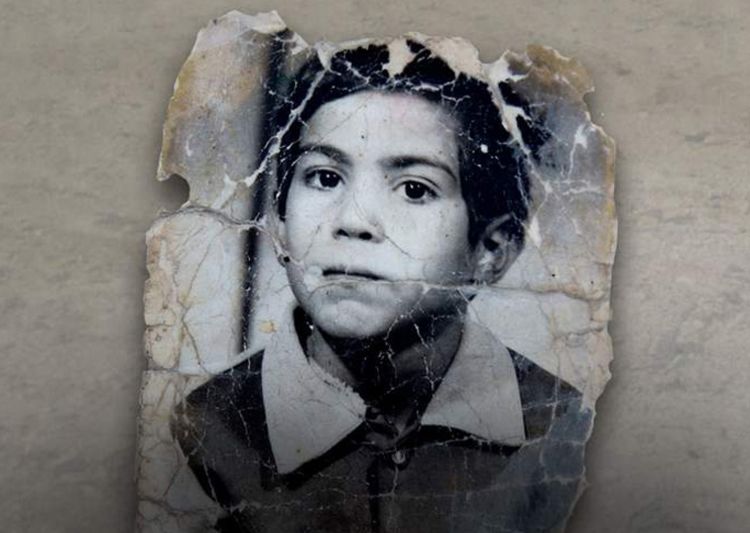

The boy in the photo

Publication date: 29 August 2019