Hunting the monkey torturers

A BBC investigation has uncovered a global monkey torture ring. This is the story of the torturers, the amateur sleuths who hunted them, and the fate of Mini, the baby monkey who became a celebrity in their twisted world.

Hunting the monkey torturers

A BBC investigation has uncovered a global monkey torture ring. This is the story of the torturers, the amateur sleuths who hunted them, and the fate of Mini, the baby monkey who became a celebrity in their twisted world.

By Joel Gunter, Rebecca Henschke and Astudestra Ajengrastri

BBC Eye Investigations

Warning: This article contains disturbing content

One night last May, unable to sleep, Lucy Kapetanich opened her laptop in the early hours. The screen lit up her tired face in the dark. She typed, “Report a crime to the FBI”, into the search bar and clicked through to the agency’s online tip form. “I have made a complaint before,” she wrote in the little box on the screen. “The monkey hate community is growing.”

Kapetanich was 55 then, a former adult dancer with big green eyes and dyed-black hair that fell in curtains around her face. For the past six months, from her small bedroom in a rundown shared house in Los Angeles, she had been slowly uncovering a global underworld of monkey torture. Her journey had begun in the pandemic, when she was doing daily webcam shows to make ends meet. The long hours on camera were taking a toll on her, so when she clicked off the webcam at night she often opened YouTube, seeking solace in cute animal videos. Her favourites were a chimpanzee family in a zoo in Japan. She could watch them for hours as she drifted towards sleep.

Kapetanich didn’t know it then, but as she watched, YouTube’s algorithm was at work on her, following her every click, saving her every preference, presenting her with new content it hoped she would watch next. Soon, when Kapetanich looked at YouTube at night, monkeys were everywhere. “All it takes is like, one click and bam, it’s all over your feed,” she said.

“The behaviour towards these monkeys is obscene, really grim,” Kapetanich said (Joel Gunter/BBC)

“The behaviour towards these monkeys is obscene, really grim,” Kapetanich said (Joel Gunter/BBC)

Kapetanich saw monkeys dressed up in baby clothes, monkeys being bathed, forced to walk upright or do other unnatural tasks. Then the algorithm served her videos of monkeys being slapped and sprayed with water. These videos violated YouTube’s terms of service, so she reported them, but the platform didn’t seem to take any action. The videos kept appearing. Kapetanich kept clicking.

Soon enough, a torture video turned up in her feed.

Lucy Kapetanich, aka “Mayhem” (Joel Gunter/BBC)

Lucy Kapetanich, aka “Mayhem” (Joel Gunter/BBC)

A little over a year ago, the BBC World Service began investigating the emergence of these monkey torture videos too. The videos appeared to be mostly coming out of Indonesia, and being uploaded to YouTube purely for the entertainment of sadists abroad. In the comments under the videos, we found a twisted community of monkey haters who seemed to be getting off on watching baby long-tailed macaques being abused.

Our investigation would lead us to Lucy Kapetanich, to Indonesia and across America and into a hidden world that was darker and more extreme than we could have imagined. The worst of the torture we found there was too depraved to describe in detail in this story, but in her quest to bring it to light, Kapetanich saw it all.

So did Dave Gooptar.

Dave “Yardfish” Gooptar. “I made it my mission to drag these people into the sunlight,” he said (Dylan Quesnel/BBC)

Dave “Yardfish” Gooptar. “I made it my mission to drag these people into the sunlight,” he said (Dylan Quesnel/BBC)

Gooptar lived 4,000 miles away from Kapetanich, in Port of Spain on the Caribbean island of Trinidad. A freelance transcriber by day, he spent some of his free time making video horror movie reviews for his small YouTube channel, called “Yardfish”. He also sometimes watched videos of baby capuchin monkeys on a farm in South Africa, and YouTube’s algorithm went to work on him too.

Gooptar wound up spending four months working on a one-hour video expose, titled “The YouTube Monkey Torture Ring: Part 1”, and in August 2021 he set it live. It didn’t garner a huge number of views. But one of them was Lucy Kapetanich.

Kapetanich had already started her own channel, “Mad Monkey Mayhem”, to try and draw attention to the abuse. When she found Gooptar’s film, she messaged him, and the pair formed a kind of alliance. For now, Kapetanich knew Gooptar only as “Yardfish” and he knew her only as “Mayhem”. Together, they began to dig.

One day, Kapetanich asked Gooptar about a monkey she had seen in video after video — a baby female. The monkey’s name was listed in the video titles, as though she was some sort of star.

Gooptar already knew who she was, he said.

“Everybody knew who Mini was.”

The first Mini video that Kapetanich saw was tame compared to what came later, but it burrowed into her brain. Mini and two other babies darted frantically around a small bathroom as the man behind the camera grabbed them by their tails and slammed them against the wall. When he did, he let out a high-pitched laugh that haunted Kapetanich. Each slam sickened her more. “The baby monkeys were exhausted and confused,” she said. “And just terrified. They had nowhere to hide.”

Dozens of videos were uploaded to YouTube showing Mini being tortured and abused

Dozens of videos were uploaded to YouTube showing Mini being tortured and abused

Kapetanich found half a dozen other monkeys on the YouTube like Mini. There was Monkey Ji, Baby Ciko, Chiro, Sweetpea, Mona — all baby long-tailed macaques being tortured on film. Some of the monkeys had developed physical tics from the stress. Monkey Ji was known for holding her head in her hands and rocking back and forth. Mini would grip her sides. The monkey haters in the comments loved it. “Abused multiple times a week since a baby. She has lived a TERRIBLE life,” someone wrote, approvingly, under a video of Mini. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen a monkey more broken.”

By that point, hundreds of different YouTube channels were posting videos of baby macaques being abused. In some, the monkeys appeared to die on screen. “Watch them try to breathe while their idiotic brains shut down,” wrote one commenter. Lucy Kapetanich was horrified by what she saw. It hurt to watch as Mini’s owner cooed an Indonesian endearment — “sayang” — to her and then smacked her in the face. It all brought Kapetanich to tears more than once. But the monkey haters loved it.

“He sayang-ed Mini and then immediately smacked her!” wrote one, screen name “Grace”.

“Man I love those videos.”

A few miles away from Lucy Kapetanich in LA, Nina Jackel, a 42-year-old animal rights activist, was also watching this world unfold on YouTube, following a tip off from a fellow activist in the UK. And as Jackel read the comments under the videos, she realised something. The monkey haters were getting frustrated. “They were making suggestions about the types of violence they wanted to see but the video makers weren’t carrying them out,” Jackel explained. “They wanted more extreme violence and they wanted control over the violence.”

Jackel, who ran the animal rights charity Lady Freethinker, realised something else, too. There was more extreme violence available. The clues were there on YouTube if you knew what to look for: invitations to join dark web forums or a messaging app called Telegram. It was on Telegram, in May 2021, that the first big private group began to take shape. The group was called “Million Tears”.

Jackel managed to obtain leaks from Million Tears, and the videos circulating inside — amputations, decapitations, drownings — confirmed that things had taken a leap from YouTube. Jackel put out a press release about the group. It didn’t get a lot of attention, but Lucy Kapetanich and Dave Gooptar saw it, and they got in touch with Jackel to tell her they were looking at these monkey sadists too. The press release spooked the creators of Million Tears into shutting the group down, but almost immediately another Telegram group sprung up in its wake. It was called “Ape’s Cage”.

Animal activist Nina Jackel was sent threats after trying to expose the monkey haters (Joel Gunter/BBC)

Animal activist Nina Jackel was sent threats after trying to expose the monkey haters (Joel Gunter/BBC)

Jackel, Kapetanich and Gooptar knew Ape’s Cage existed, but they couldn’t see inside.

Then, on 22 January 2022, an email landed in Lucy Kapetanich’s inbox, from a stranger who called himself “Ronald McDonald”.

“Please keep this between us,” he wrote. “I’m not a bad guy. I’m 48, married to my high school sweetheart, 19 year old daughter, 1 cat and my German shepherd passed away sadly of cancer.”

In the monkey hate community, “Ronald McDonald” was known by his screen name, the “Torture King”. A few months after he first wrote to her, the Torture King sent Kapetanich an email with instructions on how to download Telegram and a link to join Ape’s Cage, and when she did he vouched for her among all the monkey haters inside.

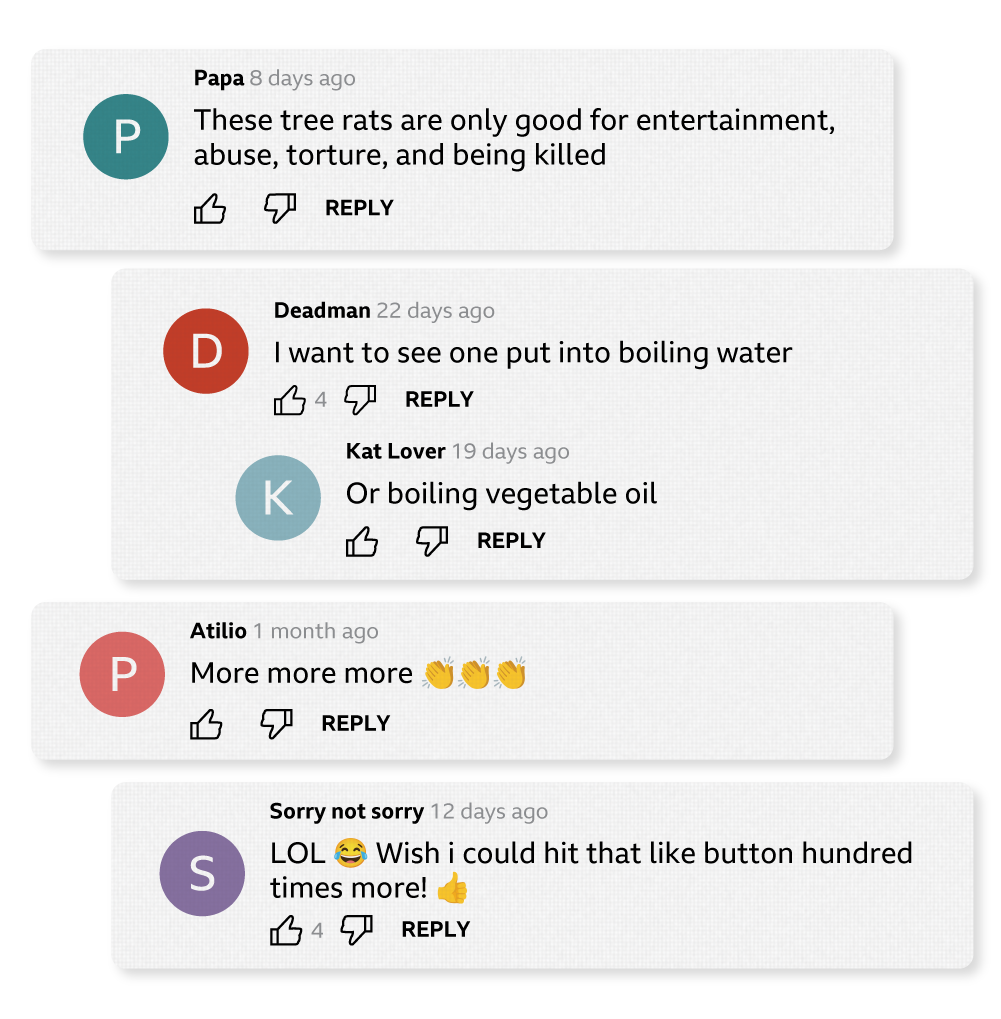

The level of abuse on YouTube, as bad as it had been, had not prepared Kapetanich for the private world of Telegram, where monkeys were known as “tree rats” and no idea for torturing them was too extreme.

Ape’s Cage contained about 400 people. The cast of characters was a mixture of the strange and — even stranger — the seemingly normal, all known to one another by their screen names. There was the Torture King, who had invited Kapetanich in; there was “Sadistic”, a gas station attendant and grandmother in rural Alabama; there was “Bones”, a former US Air Force airman from Texas with a big collection of guns; and “Champei”, who caused chaos and infighting in every group he joined. There was “Trevor”, who couldn’t contribute during daytime hours because, “no phone at work, nuclear stuff”.

And it wasn’t just Americans, there were dedicated members in Europe and Australia. Among the cruellest contributors to the group was “The Immolator”, a 35-year-old woman who loved birds and lived with her parents in the English midlands.

Kapetanich — screen name “Jane Doe” — could hardly comprehend the level of sadism she saw. At the same time, she began messaging privately with the Torture King. She was confused about why he would invite her into this world. He told her that he was ashamed of what he was doing, that he wanted to help her burn the house down from inside. He would be her mole, he said. Soon, they were messaging every day. The Torture King began to reveal his real life to her.

The Torture King at home in Virgina. “It went from baby bottle teasing to fingers being snipped off,” he said (Joel Gunter/BBC)

The Torture King at home in Virgina. “It went from baby bottle teasing to fingers being snipped off,” he said (Joel Gunter/BBC)

In real life, he was Mike McCartney, a 48-year-old former motorcycle gang member in Norfolk, Virginia, with a swastika tattoo and a “man cave” in his home decorated with Nazi symbols and Confederate flags. McCartney was well-built, heavily tattooed, and toothless from years of heroin addiction. He had spent two decades in one of America’s most dangerous outlaw motorcycle gangs, before going to prison and dropping out of that life. When the pandemic hit, he started spending a lot of time on YouTube. At some point, he saw his first monkey torture video. It was a video of Mini.

Mini’s owner was “teasing, taking the bottle out of reach”, McCartney said. The video gave him a “good chuckle”. He started watching more, leaving comments. It wasn't long before he got an invitation to a Telegram group.

“They had a poll set up,” McCartney recalled. “Do you want a hammer involved? Do you want pliers involved? Do you want a screwdriver?” He voted and came back to the app later. “And sure as heck there’s a new video with everything that was voted on,” he said. “And it was the most grotesque thing I’ve ever seen.”

McCartney saw a money-making opportunity — downloading torture videos from YouTube and selling them in Ape’s Cage. And as he sold and traded videos he became a trusted member of the monkey hate community, and rose high up in the informal pecking order.

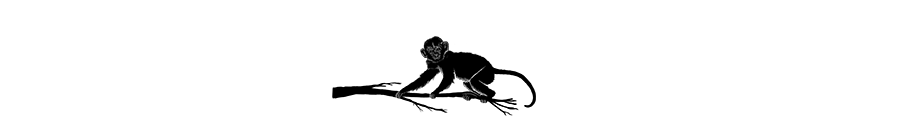

But not to the very top. At the very top of the tree there was only one man. Screen name “Mr Ape”. The Founder and CEO of Ape’s Cage.

Mr Ape spent hours every day on Telegram talking to other monkey haters and distributing new monkey torture videos to his followers. Alongside Ape’s Cage, he ran a host of other side groups — “Ape’s Chimps”; “Mr Ape’s Alpha Chimps”; “The Secret Monkey Disciplinary Academy” — and he policed the groups aggressively, trying to root out anyone he thought was an undercover animal activist.

“I’m building an empire,” he bragged one day, in one of the groups.

Mr Ape’s priority was finding himself a trusted “VO”. In the groups, VO stood for “video operator”, and referred to the people — primarily in Indonesia — who actually tortured the monkeys on camera. Mr Ape and the Torture King had both messaged Mini’s owner, via YouTube, but he refused to carry out extreme torture ideas. One member of Ape’s Cage, however, did establish access to a reliable VO, and unlike Mini’s owner, this VO seemed to be willing to do anything she asked.

And that gave Stacey Michelle Storey a lot of cache in Ape’s Cage.

Stacey Storey was a 46-year-old grandmother who worked at a gas station and lived with her son in a solitary trailer set back from the road in a rural part of Alabama. Her screen name was “Sadistic”, and she was among the most prolific contributors to Ape’s Cage. She shared endless torture videos, as well as fantasies involving forced feeding, power tools and jars of acid.

Storey’s VO charged $200 (£150) per video, she told Mr Ape. “He’s brutal and if what you want done is able to be done, he’ll do it,” she said. What Mr Ape wanted was a video that would make him famous. He and Storey ran through various ideas before Mr Ape threw out what would become his big one: baby monkey in a blender.

We found several YouTube monkey torture accounts belonging to Storey, aka “Sadistic”. Main image: Storey at the gas station where she works. (Joel Gunter/BBC)

Stacey Storey at the gas station where she works. She claimed she had been hacked. (Joel Gunter/BBC)

The members of Ape’s Cage couldn’t get enough of the blender idea. They debated how much they should send for the blender, which model would be up to the job. In April 2022, Mr Ape went to Storey with a nine-point plan for how it should be done.

The blender video was a big hit in the monkey hate community and Mr Ape basked in the fame that came from it. He and Storey commissioned more videos, including another fatal video involving a red power drill that was even harder to watch. At the same time, Storey and Mr Ape spent hours chatting privately via Telegram, mostly talking torture, but increasingly they talked security too. Hundreds of new members were joining the groups, and Storey was becoming more paranoid. “Be careful who you trust,” she warned Mr Ape one day.

What Storey didn’t know was that it was Mr Ape she couldn’t trust. A month before the blender video was made, Mr Ape had reached out to Nina Jackel, the animal rights activist, and Dave Gooptar in Trinidad, and told them he was really a kind of undercover informant. Just like the Torture King, he said he planned to bring down the monkey haters from within.

“Save the monkeys, stop the monkey torture”, he signed off his email to Jackel.

Jackel didn’t believe him — she thought he was trying to create a fake cover story for himself. Besides, she was busy trying to sue YouTube for hosting the videos, a David v Goliath case that was slowly progressing through the courts. But Dave Gooptar began talking to Mr Ape regularly.

And we contacted him too.

It turned out Mr Ape was running his empire from his mother’s house in Florida, in a nice neighbourhood with broad streets lined by picket fences and neatly-kept lawns. He was a college graduate in his mid-twenties, tall — basketball player tall — with a beard, baggy clothes and glasses. In the backyard of his house, a large oak tree shaded a cat graveyard where six cats were buried under six miniature cat headstones. Upstairs, his bedroom was a time-capsule of childhood: toys, a single bed with patterned bedspread, a framed photograph of his late father.

We decided not to name Mr Ape in this story, because of specific concerns over his safety. When we visited him, he told us he was a lonely child who had become a lonely adult. At some point, he said, his pain had morphed into hate. “What was so appealing was to see something else suffer, essentially, that looked human,” he said. “Because I was suffering.”

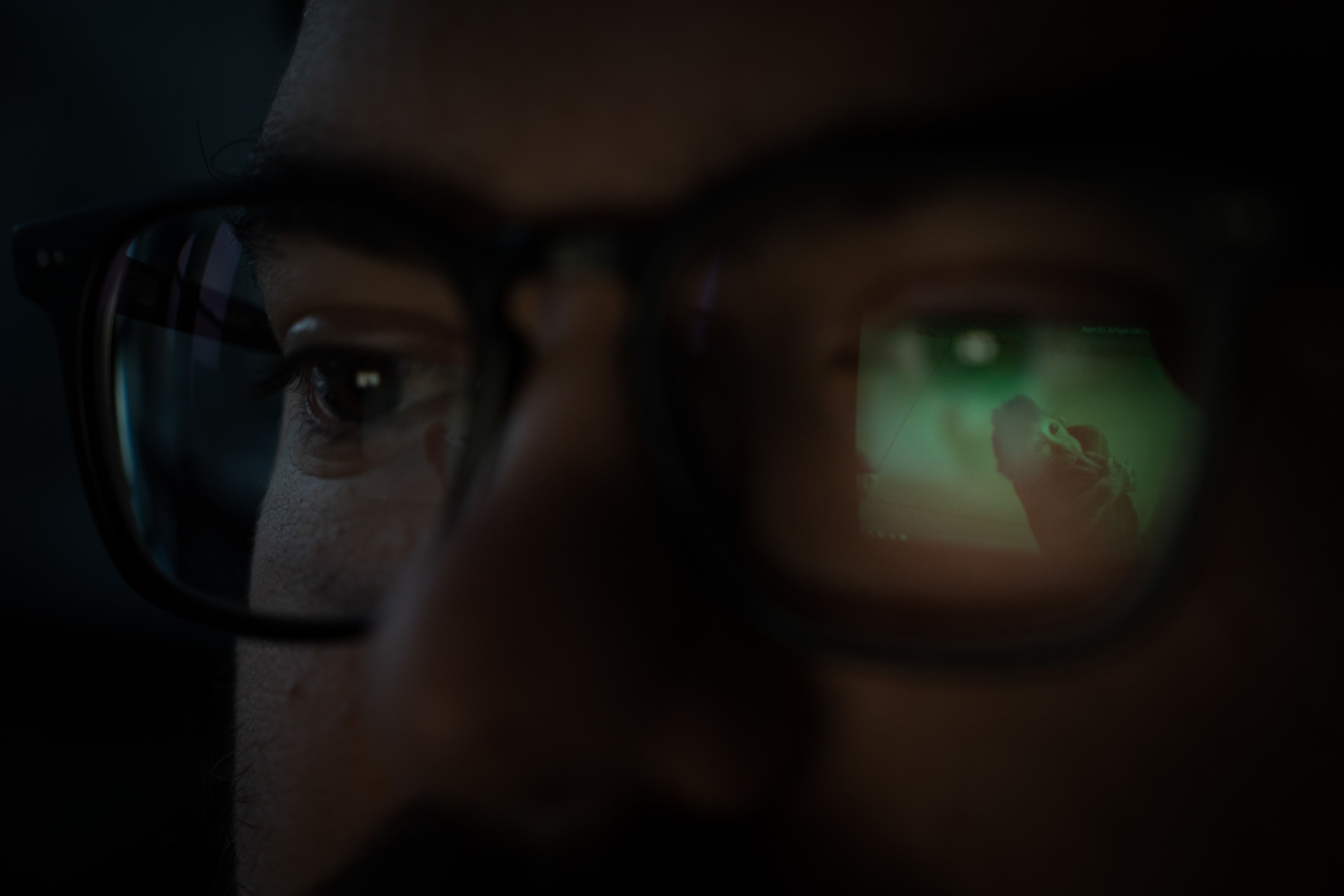

Mr Ape built up a library of thousands of monkey torture videos (Ed Ou/BBC)

Mr Ape built up a library of thousands of monkey torture videos (Ed Ou/BBC)

Mr Ape had agreed to share his files with us. He sat at the kitchen table and opened his laptop. On the screen, there was folder upon folder — “Chats”, “Finance”, “Jokes”, “Monkey”, “Off-topic”. One folder was labelled, simply, “Torture Ideas”. He had dozens of videos of Mini. He recalled an early attempt to order a video from her owner. “I wanted him to buy a baby monkey and saw it in half, vertically,” he said, shaking his head.

As for killing Mini, her owner had quoted $5,000. When Mr Ape reported that back to the group, even he was surprised about how many members were willing to put money in. But he suspected Mini’s owner would simply take the money and run. “Mini was a celebrity,” he explained. “Her owner had more to gain by keeping her alive.”

Unlike most of the tortured baby macaques, Mini had survived for a while, long enough to reach her first birthday. She became the “sadistic trophy” of the monkey hate community, the Torture King explained. “The Babe Ruth… The Marilyn Monroe… The Elvis. In this demented little circle of ours, that was Mini.”

Mini became so ubiquitous that some got bored of her. “I’m so over mini,” someone wrote, “wake me up when she’s dead.” They speculated endlessly over when she would be killed. And then, at some point, new Mini videos stopped appearing, and the monkey haters started to wonder if she really was dead.

Lucy Kapetanich watched the messages bounce back and forth, fearing the worst. She wondered if Mini was really gone. She wondered why the police in Indonesia didn't seem to be doing “a damn thing to rescue these monkeys”, why the torturers were getting away with it.

The torturers had been protected in part because the police simply weren’t paying much attention. But also because it was hard to find clues in their videos. They were smarter than their American customers — they never showed their faces or revealed their real names, and they filmed in settings that were hard to identify.

But if you really looked, there were clues.

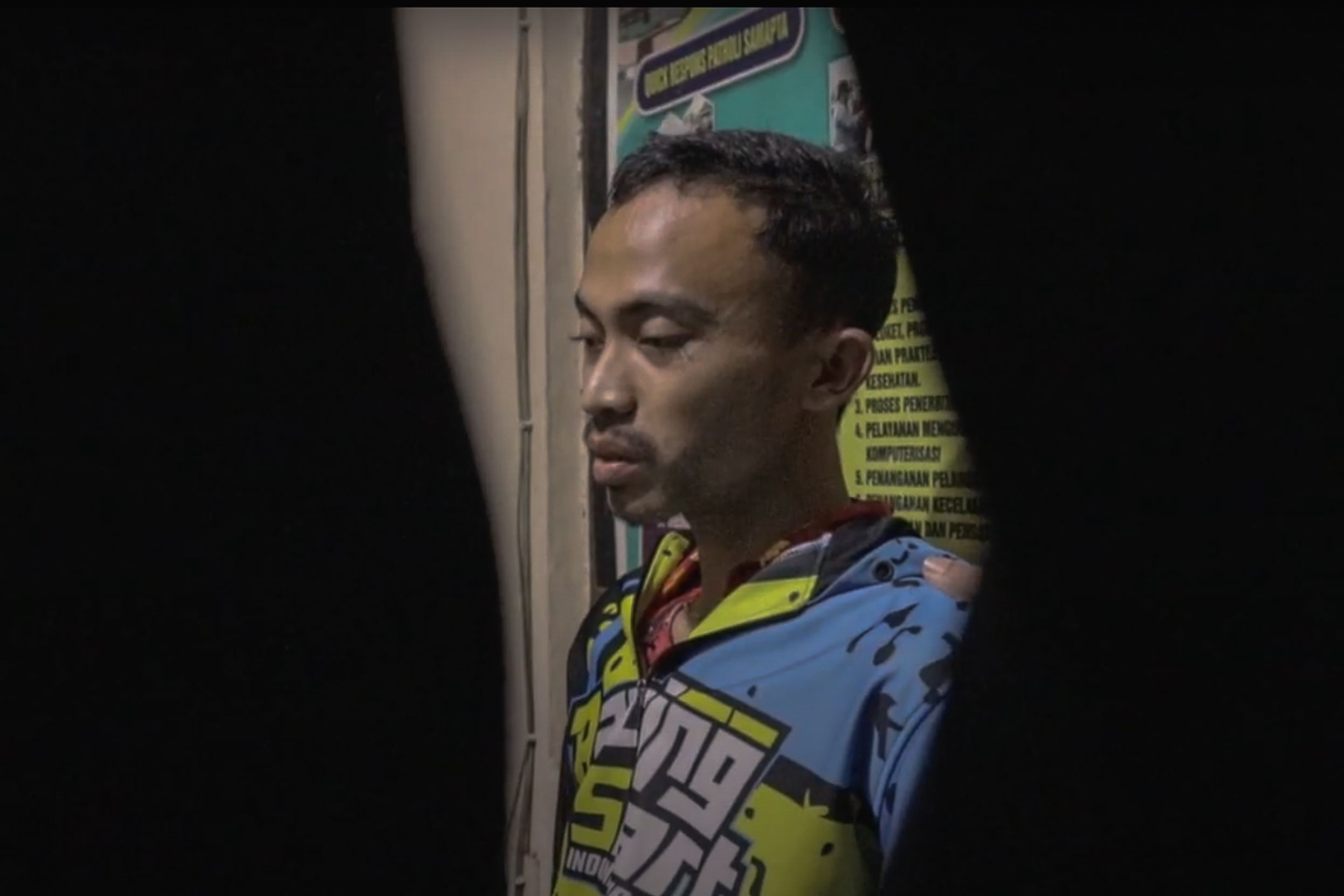

One day in Trinidad, Dave Gooptar was rewatching the videos made by Stacey Storey’s brutal VO when he spotted a distinctive set of four wooden bracelets on the VOs wrist. And there were other clues — a rice field, a river, a partial view of a house and treehouse. In the background, you could sometimes hear Sundanese, a local language used by people in the West Java region. And Gooptar spotted something else — a licence plate visible on a moped. He sent it to us, and we matched the registration to a name and address in the Ciamis Regency area of West Java, where the neighbourhoods border a forest that is home to hundreds of long-tailed macaques.

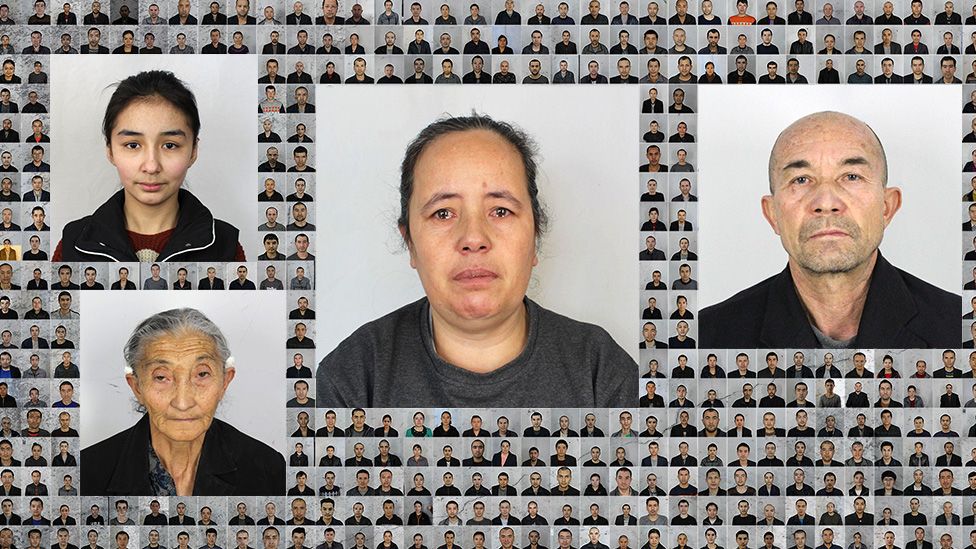

Clues in Asep’s videos eventually led us to his name and location

Clues in Asep’s videos eventually led us to his name and location

Clues in Asep’s videos eventually led us to his name and location

Clues in Asep’s videos eventually led us to his name and location

The name was also linked to a Facebook account, and on the Facebook account we found a short video clip of a young man posing with a familiar red power drill. And he was wearing four wooden bracelets.

It turned out that Asep Yadi Nurul Hikmah was already on the radar of local animal groups, because he was selling protected species — a more serious crime in Indonesia than torturing an unprotected species like the long-tailed macaque. With a local animal charity, we arranged for discreet filming of the address registered to Asep, and when the footage came back, there was the treehouse from the torture videos. This was where Stacey Storey’s VO lived.

The animal charity tipped off the local police, and they set up a sting and caught Asep at an empty market at night with boxes of baby monkeys. When the officers raided his house, according to their records, they found a white Sanex blender, a red power drill, and a set of four wooden bracelets.

Stacey Storey’s brutal VO was in custody.

Asep Yadi Nurul Hikmah is taken into custody by police

Asep Yadi Nurul Hikmah is taken into custody by police

Asep Yadi Nurul Hikmah is taken into custody by police

Asep Yadi Nurul Hikmah is taken into custody by police

Three hundred miles away, in Central Java, police there were closing in on a different address. We had also set out to find Mini’s owner, by messaging him privately posing as a monkey hater. We found out that he ran a second-hand clothes business on Facebook that was linked to an address. One day we visited him at home, going undercover as a potential video buyer. M Ajis Rasajana lived with his wife and infant son in a modern two-storey family house, tucked away at the end of a long road opposite a rice paddy that was recognisable from his torture videos.

We alerted the police to Ajis’s address, and when they knocked on his door he came willingly to the station. After a few hours of questioning, he was released and went home, and the next day we visited him again, not undercover this time, to ask him about his crimes.

Ajis Rasjana holds Mini, in undercover filming by the BBC

Ajis Rasjana holds Mini, in undercover filming by the BBC

When Ajis first started posting monkey videos on YouTube, he was surprised by how many views he got. “I wanted to have a lot of viewers, because then I can get the money from YouTube ads,” he said. He noticed that abusive videos got more views, so he made more abusive videos. Soon foreigners began to message him. He set up a Telegram account and advertised it on YouTube. “Message for more extreme videos,” he wrote. And they did. The foreign customers were “psychopaths”, Ajis said. But he made enough from them to buy a new car.

By the time he purchased Mini, when she was just a few days old, he had killed 20 other monkeys through abuse or neglect, he said. But he managed to keep Mini alive, and she became his star. And he tortured her for a year, right to the very end.

“When I remember her I feel really sorry,” Ajis said, crying again.

“Even though I was evil to her, she loved me.”

The FBI eventually came to interview Lucy Kapetanich, after her second online tip off, and she handed them all of the evidence she had gathered. Then months went by with no developments and she was beginning to get frustrated. But unknown to Kapetanich, other law enforcement agencies had received tip offs too. One day last summer, a casefile landed on the desk of Special Agent Paul Wolpert at the Department of Homeland Security, about a ring of monkey torture enthusiasts across the US. Agent Wolpert normally went after child sexual abuse gangs, and he wondered why the hell he was looking at a case about monkeys. “It was so out there,” Agent Wolpert recalled, shaking his head. “Like nothing I’d ever seen.” The more he looked at it though, the more it began to make sense. “It’s actually just like a child abuse investigation,” he said. “The groups, the secrecy, the way they vet people — it’s exactly the same.”

Special Agent Paul Wolpert. “It's just so out there,” he said. (Joel Gunter/BBC)

Special Agent Paul Wolpert. “It's just so out there,” he said. (Joel Gunter/BBC)

Possession of animal torture videos isn’t necessarily illegal in the US, but distribution is, and punishable by up to seven years in prison. So Wolpert began to follow the money. Stacey “Sadistic” Storey had been using a Cash App account registered in her real name. The Torture King and Mr Ape had both sent and accepted transfers too. Money was bouncing all over the place with real names and phone numbers attached. And as Wolpert combed through the exported Telegram chats, he saw the group members getting brazen to the point of stupidity. When they weren’t talking torture, they talked about their children, pets, where they lived and worked. One day, the Torture King had told his group that they all needed to trust each other and build a strong community, so they should all post their real picture and name in the chat. And they did.

Agent Wolpert couldn’t believe the idiocy of it all. The Torture King had claimed he’d done it to help identify the monkey haters, but of course it helped the authorities to identify him too. Wolpert sent a team to set up surveillance cameras on a telephone pole opposite McCartney’s house, and a few weeks later, wary that McCartney might be armed, a SWAT team descended on his house.

As Homeland Security agents searched the property, Wolpert questioned McCartney, seized his devices, and then let him go. We had obtained McCartney’s address, from a public records website, and we went to knock on his door too. Sitting in his garage-turned-man cave, he recalled the rush of first rising up in the monkey hate community. It was like the old motorcycle gang days again, he said. “I loved the respect."

Mike “Torture King” McCartney faces up to seven years in prison (Joel Gunter/BBC)

Mike “Torture King” McCartney faces up to seven years in prison (Joel Gunter/BBC)

McCartney traded and sold hundreds of videos. Soon he was the “king of this demented world”, he said, with a smile. “I was the man. You want to see monkeys get messed up? I could bring it to you.” He liked the money too. But he was selling videos for just a few bucks a pop. He had probably made only a few hundred dollars in total. And now he was facing up to seven years behind bars.

McCartney was hoping that Agent Wolpert would look kindly on him for inviting Lucy Kapetanich into the groups, but it didn't seem likely.

“I tried to do the right thing,” the Torture King said, dejectedly.

“But I profited. That was my mistake.”

Homeland Security agents had fanned out across the rest of the country too. When they knocked on Stacey “Sadistic” Storey’s trailer in Alabama, she denied responsibility and told them she’d been hacked. When we visited her, at the gas station where she worked, she told us the same thing. But the Homeland Security agents had taken away her phone, and they found nearly 100 torture videos on it. It also showed that she had rejoined a new torture group in April this year and was still active in it last week. Her Cash App records prove, among other things, that she ordered the blender video. “The evidence is there,” Agent Wolpert said.

From the big three, that left Mr Ape. No-one had knocked on his door yet, but it was only a matter of time.

“Ape’s Cage was a moment in monkey hate history,” Mr Ape said (Ed Ou/BBC)

“Ape’s Cage was a moment in monkey hate history,” Mr Ape said (Ed Ou/BBC)

Mr Ape had confessed to us that he was personally responsible for the deaths of at least four monkeys, and the torture of many more. He confessed to commissioning “extremely brutal” videos with Stacey Storey. He said that he was ashamed, and he said he could “remember the face of every monkey and how they died”.

But when Mr Ape spoke, some pride came through the shame. Ape’s Cage had been a “moment in monkey hate history,” he said, with a trace of a smile. He claimed, like the Torture King, that he had really been in the monkey hate groups to expose the others. The Telegram group he set up was “a front, essentially, to catch the people who were involved”. But he wanted to catch them so bad that he got “too into character”, and ended up running the show.

Mr Ape might have represented the best chance to shed some light on the unanswered question at the dark heart of the monkey torture world — the why. But no matter how long you spoke to him, he never seemed to be telling the full truth, only spinning some version of it. We consulted Dr Stacey Cecchet, a psychologist who is assisting US police with their monkey torture investigations, and she dismissed his claim that he had been simply trying to alleviate his own suffering. “Individuals like this have usually had these desires for a long time,” Dr Cecchet said. “So I find it hard to believe someone could go through a difficult period in their life and suddenly think, ‘You know what would make me feel better? Watching an infant monkey being sawed in half.’”

Dr Stacey Cecchet is assisting police with their monkey torture cases (Joel Gunter/BBC)

Dr Stacey Cecchet is assisting police with their monkey torture cases (Joel Gunter/BBC)

The world of bespoke monkey torture was new to Dr Cecchet, but the elements were familiar, she said. It reminded her, like it reminded Agent Wolpert, of child abuse gangs. It was a world where sadists could “access what is most exciting to them, and not only access it but have it custom made,” she said. As for Mr Ape’s claim that he was an undercover agent, it was just an example of the “detail rich fantasy life” often lived by sadists. “They learn to live in this fantasy world,” she said.

Special Agent Wolpert didn’t believe in the fantasy either. So all that was left for Mr Ape was to wait for the federal agents to arrive.

As he waited, he was still thinking about Mini. He had once obsessed over her. Now he was wondering if she might still be alive.

“She probably couldn’t go back into the wild now, given the hierarchy of the troops, she would probably just starve,” he said.

“But there’s nothing I wouldn't give to see her in a good home.”

In the hills outside of Bandung in West Java, Indonesia, where strawberries and avocados and chilli plants grow on terraces of fields carved into the hillsides, there is a road that leads up past groves of bamboo trees to a shaded sanctuary about the size of a football pitch. There, a team of vets rehabilitates rescued animals and animals who cannot live in the wild. There are leopard cats, pangolins and peacocks, and a sick sea eagle who can’t fly. There is a crocodile who attacked too many people. In one corner of the sanctuary, there is a large cage filled with foliage, tree branches and a tyre swing, and in it is Mini.

When Mini arrived at the sanctuary, after the police rescued her, she had fractures in her tail and jaw and her baby teeth were all broken or missing. She was deeply stressed, the vet, Ilham Maulana, said. And yet, after just four months, when we visited her, there had already been a change in Mini. She had become braver, more curious. She had begun to swing around the cage, leaping over other monkeys and play fighting with them.

When Mini has recovered a little more, and learned a little more, the team will be able to return her to the wild, said Femke de Haas, the co-founder of the sanctuary. “We have a beautiful area that we can use as a release site for this species,” De Haas said. “And it is a pristine forested island in a protected reserve, so people are not allowed to go there,” she said. “So it is safe.”

Mini at the Jakarta Animal Aid Network sanctuary. She will be released into the wild (Anindita Gunita/BBC)

Mini at the Jakarta Animal Aid Network sanctuary. She will be released into the wild (Anindita Gunita/BBC)

As Mini was settling into her sanctuary home, her former owner, Ajis Rasajana, was sentenced to eight months in prison — the maximum penalty available. It was significantly less than the three years that Stacey Storey’s VO Asep would get, simply because Asep was also selling protected species. Eight months for Mini’s owner was not enough, the judge in his case said, as he handed the sentence down.

In the US, things were moving more slowly. But Agent Wolpert was hopeful of convictions for Mr Ape, Stacey Storey and Mike McCartney. “I just don’t think the judges are going to take kindly to this one,” he said, shaking his head.

In LA, Nina Jackel was still trying to sue YouTube for hosting the videos, but a judge had already ruled in YouTube’s favour and she was facing a long and uncertain fight ahead.

In a statement, YouTube told us that animal abuse had “no place” on the platform and the company was “working hard to quickly remove violative content”. “Just this year alone, we’ve removed hundreds of thousands of videos and terminated thousands of channels for violating our violent and graphic policies,” the statement said. Telegram told us it was committed to protecting privacy and freedom of speech and its moderators could not “proactively patrol private groups”. But users could report content from those groups to Telegram moderators, it said.

It is still possible, with a simple search, to find troubling monkey videos on YouTube, but the worst of the torture appears to have gone. On Telegram, it is alive and kicking. And Facebook is now home to at least dozens of monkey torture groups, some with with thousands of members. Facebook told the BBC it had removed the groups we brought to the company’s attention recently. “We don’t allow the promotion of animal abuse on our platforms and we remove this content when we become aware of it, like we did in this case,” a spokesperson said.

Lucy Kapetanich lights up on the patio. “It was really dark,” she said. “What kept me going was Mini.” (Joel Gunter/BBC)

Lucy Kapetanich lights up on the patio. “It was really dark,” she said. “What kept me going was Mini.” (Joel Gunter/BBC)

In Trinidad, Dave Gooptar is still tracking the groups — exporting membership lists, identifying buyers and VOs. He is finding it hard to let go. He called Kapetanich recently, while we were visiting her, and found her sitting smoking on the patio under a vivid, orange LA sky. The two of them fell right into it, Mayhem and Yardfish, the two most famous amateur sleuths in the monkey torture world. Kapetanich told Gooptar the good news about Mini. Earlier that day, she had seen footage from the sanctuary, and stared intently at the screen as Mini swung from branch to branch. “I thought Mini had died,” she had said afterwards, trying to hold back tears. “Wow, that was really emotional.”

Kapetanich joked with Gooptar about what the hell they were going to do when it was all over. “I dunno, go to monkey torture anonymous?” she said.

She did have a plan, she said, for the day when there were no more groups, no images or videos. She was going to take her pink hard drive, which she had carried around for more than a year, which was filled with all the worst of it all, and pour tequila on it and smash it up.

“Baby, that’s so stupid,” she said, laughing. Then, looking serious again, she said: “But no, honestly, I really want to destroy that thing.”

It was late. Kapetanich settled into her patio chair, took a drag of her cigarette and blew smoke up into the sky. She looked happier than usual, more at peace.

On the other side of the world, Mini was nearly free.

You can watch the documentary, The Monkey Haters, on BBC iPlayer, and listen to the radio version on BBC Sounds.

Investigation

Astudestra Ajengrastri, Joel Gunter, Rebecca Henschke, Sam Piranty, Kelvin Brown

Online production

James Percy

Graphics

Asher Isbrucker, Manuella Bonomi, Dwiki Marta

Published 20 June 2023