The crisis in care

Who pays?

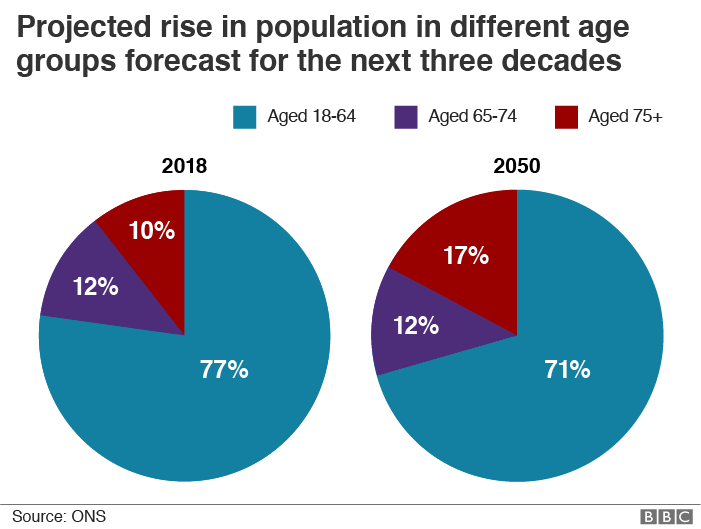

Over 10 months, a small team from the BBC’s Panorama programme documented the realities of how the care system is working in England. Based in Somerset, they followed the stories of people needing care and of the people trying to provide it. The pressures faced here are being felt across the country as the demand for help from an ageing population increases and local authorities struggle with tight finances.

Jean and Owen

“I won't forget you,” whispers 87-year-old Jean Chapman to the care worker, who has leaned forward to hear her words more clearly. “I’ll miss you too,” the woman replies, reaching forward to hold Jean’s hand. Other staff kiss Jean goodbye as she is pushed in her wheelchair towards a waiting ambulance.

Jean and her 96-year-old husband Owen are moving because their care home, where they have lived for a year, is closing.

“It’s incredibly sad,” says their son-in-law, Nigel. “We thought we’d found the care home from heaven really with the support here, the carers here. We just hope and pray that this is going to be the last change for them.”

Popham Court, an elegant cream-fronted building in Wellington, Somerset, is closing because it’s in need of modernisation but there isn’t the money to do it. According to the then chief executive of the not-for-profit company that ran it, council fees don’t cover the costs.

“I’ve been on the board of Somerset Care for seven years,” says Jane Townson. “And at no point has the home not made a loss. We’ve been losing money for years and we’re talking hundreds of thousands of pounds.”

Jean and Owen, who both have dementia, are heading to another home run by the company seven miles away. Over six months last year, at least 2,500 frail, elderly people in England had to move because their care home closed - a 39% rise on the same period in the previous year. It is one sign of the increasing pressures on a care system which is meant to look after some of the most vulnerable people in our society.

Local authorities provide adult social care - support with day-to-day tasks like washing, dressing and medication either in a care home or in someone’s own home. To be eligible you have to show you have a significant need for help and in England you have to have savings and assets of less than £23,250. The care systems in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland operate in slightly different ways, but many of the pressures they face are the same.

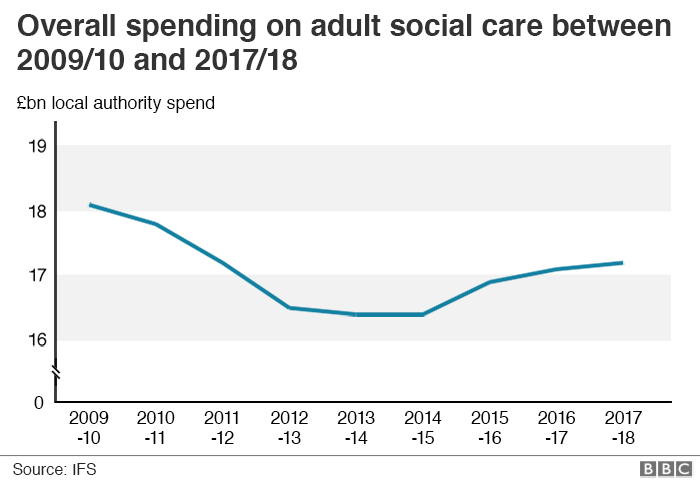

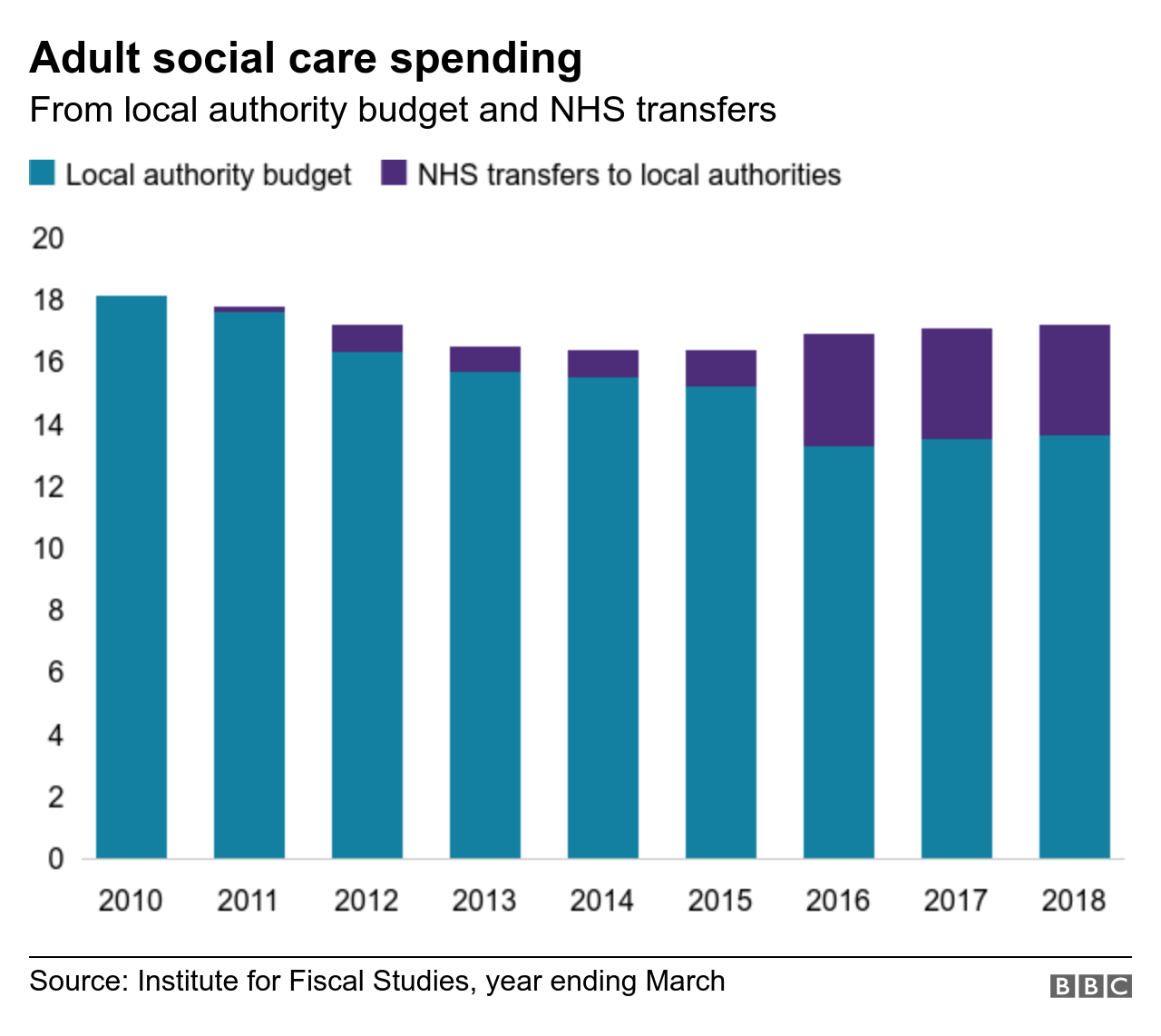

The ageing population means more people need help as they live longer with more complex conditions. In England, councils spend about £15bn a year from their own budgets on adult social care. In addition, they get some money from the NHS and many of those who qualify for council care have to make contributions to the cost. This brings the total amount local authorities spend on care services to around £21bn.

But since 2010, councils in England have had the money they receive from central government cut by nearly half, as part of the government’s austerity measures. Some of that loss has been offset by increasing local taxes, but the amount they can spend on all the services they provide from fixing potholes to libraries to social care, has been cut by almost 30% during that time.

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesperson says it is “committed to ensuring everyone has access to the care and support they need, and have provided local authorities with access to up to £3.6bn more dedicated funding for adult social care this year and up to £3.9bn for next year".

The government says councils’ access to additional dedicated funding for adult social care is worth up to £3.6bn this year and will increase to £3.9bn in 2019/20.

Even so, many councils say they remain under intense financial pressure. Last year, Jean and Owen’s local authority, Somerset County Council, came close to going bust. It had to make £13m worth of cuts to balance its books. Part of the problem has been overspending in areas such as children’s services, but the cuts are being made across the authority.

Stephen Chandler, who runs adult social care in the county, has had to find £9m worth of savings from his budget of nearly £140m. In the year ahead, he must find another £4m of cuts.

“It is really difficult,” says Stephen. “What I say to my staff is, think about what you would want for you, your loved ones. But for me, I’m thinking about how am I going to afford that? We’re talking about costs that can be anything from £1,000 to £2,000, or £3,000 a week.”

Stephen is in charge of providing care for about 6,500 people in Somerset and spending on adult social care takes nearly half of the council’s budget.

In the months that we follow him and his team, it’s clear how heavily this complicated balancing act weighs on him. “We’ve become good at ensuring that our money is only spent on those people with the most complex of needs. We can do that for a little bit longer but not much longer."

Despite the growing demand for support, fewer people now qualify for council-funded care than did in 2010. This is partly because the financial threshold for receiving support hasn’t risen with inflation.

Many, like Jean and Owen Chapman, spend years bouncing round what has become a very confusing system.

Seven years ago, the Chapmans were struggling to cope and asked for council help. As they were living in the family home, its value was not included in the financial assessment and their savings were below the £23,250 threshold. It meant they got local authority help.

When living in the house became unmanageable for them, they downsized to a flat. The extra money from the sale of the house meant their savings were taken above £23,250 and they had to fund their care privately, according to their daughter Helen.

“That ticked along for quite a while until the amount of savings they had dropped to the minimum whereby they went back on to state care,” she says.

Now they are both in residential care, the pattern is being repeated. The value of their home is now included in the council’s calculations, so it is being sold to pay for their care.

“That money will then go into their bank account for use paying for the care home for as long as it lasts. When that is gone I assume they will go back to being state-funded again,” says Helen.

But while they are self-funders, they will also be helping prop up the care system.

Watch more on this story

A 2017 report by the Competitions and Markets Authority estimated that on average self-funders paid £44,000 a year for a care home place - £12,000 more than the average paid by councils for a place.

Jane Townson, who has now moved from Somerset Care to become chief executive of the United Kingdom Homecare Association, says that self-funders subsidising the lower fees paid by councils in care homes is endemic.

“We completely disagree with this, as a matter of principle…. It is a national problem and it is wrong, but what can you do if you want to keep the whole care sector afloat?”

Home care companies are more likely to focus either on state-funded clients or on self-funders.

At their new care home, Lavender Court, Jean and Owen have rooms next to each other.

Jean is wheeled into Owen’s room to sit with him. “I want to go home,” she says as she is hoisted into an armchair next to her husband. “You are in your new home and we are going to look after you,” the care worker reassures her.

When we visit four months later they seem to have settled. Their daughter Helen and son-in-law, Nigel are pleased with the care they are getting. The couple’s flat has been sold and that will pay for their bills for about 10 months before it runs out. Then the council will take over the cost of their care again. Some care homes won’t accept the lower rate paid by councils – at the back of Nigel and Helen’s minds is the worry that the elderly couple could be asked to move again.

Like many families they have found navigating the care system takes its toll.

“It’s exhausting, are you exhausted?” says Nigel, turning to Helen. “It’s been a long haul,” she replies. “Not physical weariness, it’s the mental fatigue of trying to hold it all together. Making sure you are doing the right things for them at the right time.”

Nigel says the current system is a mess. “Families need to know what to expect when they care for their relatives in the future,” he says. “How to access the care, how to access the funds and everything like that, and it is a worry and it won’t go away.”

On 7 February, Owen died peacefully.

Local authorities supply long-term social care to more than half a million elderly people like Jean and Owen

Martine

It’s a beautiful sunny day in June and three little boys are playing on their trampoline. Their father ducks below the level of the trampoline, out of their sight. There are shrieks of joy as he suddenly reappears. The sound of the fun drifts into the house, where their mother sits in an armchair, her arms and legs heavily strapped.

Martine Evans is 37 and has idiopathic juvenile arthritis. Movement has become increasingly painful for her, making it impossible for her to join her husband, David, and their three-year-old triplets in the games being played in the garden.

Martine’s health began to deteriorate soon after giving birth.

“About six months after they were born, my arthritis just went haywire and every joint is now highly arthritic,” says Martine. “And I’ve also snapped a tendon, due to the arthritis.”

Martine Evans

Martine Evans

This means she relies on David for nearly everything. Somerset County Council pays for a nanny to help with the boys some of the time, but David still has to juggle looking after them with working as a self-employed mechanic and caring for Martine.

After months of doing this he is exhausted. “I’ve been awake hourly during the night some nights, sometimes more. I barely sleep at night, then I’m awake all day,” he says. “I knew there would be care needed at some point and for the rest of her life, but didn’t expect it quite so soon.”

David Evans is Martine's husband and carer

David Evans is Martine's husband and carer

The couple have gone back to the council to ask for help with Martine’s care during the day and if possible at night. Sara Sharratt, an occupational therapist, who is part of the authority’s West Somerset social work team, is on her way to see them. A specialised bed has just been delivered to the family, which Sara hopes will make their lives easier. By pressing buttons on the hand control, Martine should be able to move herself a little. “I have ordered a profiling bed for her which would give her a bit of independence in terms of control,” says Sara. “She can sit up, get her feet up.”

But when Sara arrives at Martine and David’s home, it quickly becomes clear that the bed isn’t doing what they need it to do. “I’m just getting folded like a sandwich,” says Martine as the bed raises her up.” Sara agrees it’s not working. She’s also worried when she sees David lifting Martine from the bed back to her armchair.

“It’s the first time I’ve actually seen you do that physically,” she says to David.

“Yeah, I’ve told you he is going to kill himself,” Martine responds. Sara nods, “Yes, it’s not just a simple lift. Right, I need to get a bed ASAP.”

She will also get a hoist so David doesn’t have the strain of lifting Martine several times a day. Getting the right equipment is important because it allows the family to have more control over their own lives. It will also keep costs down for the council.

“What is challenging for us as a council is to keep her at home,” says Sara later. “It is incredibly costly, or will be incredibly costly, but for her I think it’s really important that she stays at home just to maintain that family life, bring back a little bit of normality because I think at the minute those lines are all skewed. Her husband isn’t a husband, he’s a carer. It’s hard.”

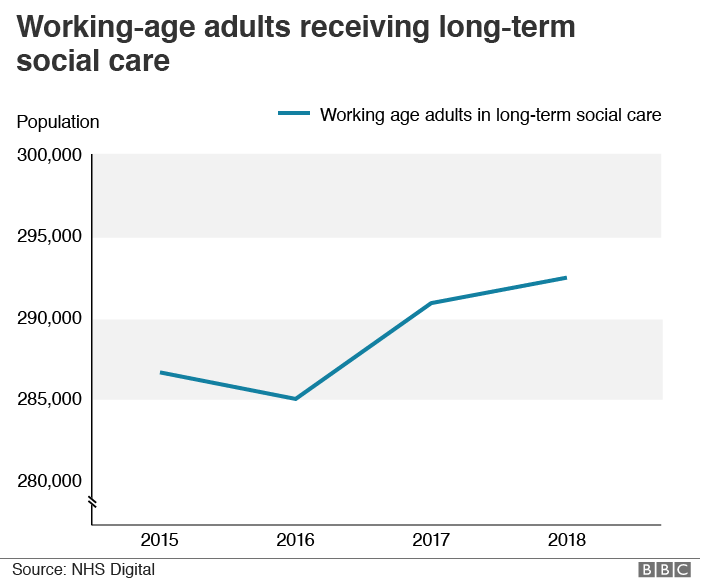

Nearly half of the money that local authorities currently spend on adult social care goes on younger people with disabilities. Over the 20 years to 2040 spending on this group is expected to more than double.

Cases like Martine’s underline the pressures being faced by social work teams across the country as they juggle the needs of the people they are seeing, along with the squeeze on council budgets. Somerset’s financial problems mean all spending is closely scrutinised. The social work team is usually expected to keep the cost of packages of care provided in someone’s own home below a benchmark of £540 a week. That is what the authority would pay for a place in a residential home.

Martine needs visits from carers four times a day. The cost of that, added to help with childcare, comes to more than £600 a week. For the moment, the help the family is desperate for at night is off the agenda.

Chris Denovan leads the West Somerset social work team. She has the difficult job of balancing Martine’s need for support against all the other people needing help in her patch. She’s spent her working life in social care teams in the county and she exudes warmth as she talks about what they do.

“I love it because I came into it wanting to make a difference. That passion has never gone away.”

When I ask Chris how she felt when she was told there was a danger of the council going bust, her response is quick. “My first reaction was over my dead body…. because it is the last thing that I want to happen to Somerset.”

But balancing the financial pressures and staff shortages with increasing demand for help has been extremely difficult.

“This has been the toughest year of my working life,” she says. “And my service years have been over 40. We have had to make decisions that I have never had to make [before].”

Chris has to get the spending on Martine’s case approved by her boss. She worries that if the cost of keeping Martine at home rises too much then they and the family may face a dilemma.

“It is never our decision to say that someone has to go into a residential placement,” says Chris. “What we say is, this is the personal budget we can give you and it is of course for them as a family to make the decision how they spend that money.”

Within three months, it is clear that Martine and David can’t go on without help at night.

“David is absolutely exhausted which is terrible”, says Martine. “He doesn’t complain. He just carries on, he is amazing. He’s falling asleep on his feet, bless him. I just feel so guilty that I’m causing him this much sleep deprivation. We should be a team and working together and not me being a weak link all of the time.”

Everybody wants to help... they are continually hamstrung by the budget

David is sleeping on the floor beside Martine’s bed so he can be there as soon as she calls.

“Drinks, painkillers, toilet, turning to make her comfortable, I can do that four-five times an hour in one night," says David. “You keep going for the things you love, I suppose.”

By December, the council agrees to pay for a carer to come in two nights a week to give David the chance to sleep. This brings the cost of Martine’s care to more than £900 a week. The council has also applied to the NHS for funding for her care. When that is agreed, the number of nights of help the family get is increased to five.

As Martine lies on her bed, the noise of family life surrounds her. Above, she can hear David getting the children bathed and changed. She finds it difficult not being able to help settle the boys for the night. For the family, coping with Martine’s deteriorating health has been hard enough without the added complication of trying to get enough support. When she reflects on their experience of the care system her thoughts are not about them, but about the people who’ve tried to help them.

“Our social worker has gone out and fought tooth-and-nail for us to get that,” says Martine. “The social workers, the key workers, occupational therapists, everybody wants to help. And they are continually hamstrung by the budget.”

Martine is one of almost 300,000 working-age adults receiving long-term care

Rita

For many people, the line between what the NHS will help with and what local authorities will do is a blur. That’s certainly what Rita McAllister’s family has found.

“I don’t think you realise what goes on until you are involved in the system,” says Rita’s daughter, Siobhan Madden. Rita, 77, is sitting in her armchair watching the world out of her window. The other side of the glass, the streets of Taunton are set out in a patchwork before them.

Rita has Parkinson’s disease and needs a lot of help. For a long time, she was cared for at home by her family. Siobhan gave up her job to look after Rita for six years, but as Rita’s health deteriorated they needed more help. At first, because of Rita’s very high needs, the NHS paid for her social care under a scheme called Continuing Health Care - the same scheme that eventually provided support for Martine Evans.

The social care provided by the NHS is not means-tested and is only available for those assessed with the highest health needs. But many people don’t realise that. A recent poll for the Local Government Association found that 44% of people questioned believed that the NHS provides adult social care for everyone, not councils, and 28% thought generally social care was free.

When someone does qualify for health-service-funded social care, they often find their budget is more generous than it is when they are supported by their council. Rita’s health seemed to improve with the level of support the NHS was providing and her family believed that because it was working well, it would continue. But a year later in 2017, Rita’s case was reviewed. It was decided she no longer met the criteria for free NHS social care. Even though her family argued that it was the level of support she was getting that had stabilised her condition, NHS funding was withdrawn.

This meant responsibility for her care now fell to Somerset County Council, but it wouldn’t pay for as much support. The family were already doing a lot of care. Now they had to fill in the gaps.

“Obviously Siobhan was getting tired,” Rita’s son Sean says. “It was difficult for me because I was working full time. If I was staying the night I might be up for long periods, and then going straight to work. Over a period of time that becomes quite draining and difficult to manage.”

Siobhan became ill and her mother’s health got worse too. Rita’s pain levels were increasingly hard to manage and eventually she ended up in hospital. From there, she was moved to a nursing home. Once again, the question of who will pay for her care is being discussed. With Rita in a nursing home, the value of her home is now included in the council’s financial calculations. It means she is expected to sell the house she loves.

Georgia Ayling, Rita’s social worker, has got to know the family well over the past few months.

“Rita has very, very strongly said all the way through she doesn’t want to sell her home. It will be a situation she is forced into if funding comes back to the local authority,” says Georgia. “I can’t agree with it, but it is the way it is. There are no allowances for people, because everyone who has social care is in the same situation.”

“They moved into this house in 1964,” says Siobhan standing in the kitchen of her mother’s home. “They were the first people to move in as a council house and eventually they bought it.”

Lined up on top of a cupboard are teapots of all shapes, sizes and patterns. Siobhan and her brother Sean chuckle at the memories of how their Mum would welcome everyone into their home with the offer of a cup of tea and a chat. “Everyone would leave feeling better,” says Sean, smiling.

Rita’s children accept the house may have to be sold, but say it will break their mother’s heart.

It seems like a cop-out to say if you’ve got an illness that is progressive... then you have to fund yourself

“It is like being penalised, for being ill and seemingly doing the right thing for your family and buying your property.”

“I appreciate care costs a lot of money,” says Sean, “but Mum did not ask to be where she is. It seems like a cop-out to say if you’ve got an illness that is progressive, that’s not going to get better, then you have to fund yourself.”

The alternative is to once again apply to the NHS for Continuing Health Care funding. Social worker Georgia has been helping the family fill out the forms in what all of them find a complicated process.

A photo of Rita as a young mother

A photo of Rita as a young mother

“Rita’s health is very, very complex,” says Georgia. “It’s an expensive package of care, with a lot of care going in because of Rita’s complex needs. I relied very heavily on the Parkinson's nurse to support the risk assessments and to give me the information about the support and care that Rita needed.”

On a cold January day Georgia and Rita’s children arrive at the nursing home to meet a nurse assessor. She will go through a checklist to decide whether Rita’s needs meet their criteria. The meeting lasts a couple of hours. Georgia emerges from it feeling hopeful, but they won’t know the decision for several weeks.

The whole system of what happens when you become this ill is horrendous really

“I think that Rita should always have been health-funded,” she says. “But I don’t know, I simply can’t say what the outcome is going to be.” The information gathered by the assessor now goes to a panel which will decide whether or not Rita once again qualifies for NHS-funded care.

Three weeks later, the family receive a letter telling them that the health service will pay for Rita’s care. It’s a relief, but the decision will be reviewed in three months.

“What's going to change really in three months? It's a progressive disease,” says Siobhan as she and her brother sit at the table in the kitchen of their mother’s house. “She's not going to get any better. It's just ridiculous really. The whole system of what happens when you become this ill is horrendous really. It's so long-winded, it's so stressful for the family and for Mum.”

“From what I’ve seen it seems to be a battle,” says Sean. “Health wants social care to pay, social care wants health to pay so you’ve got to go through these assessment processes to determine, is it health need? Is it a social need? We’ve been through that and gone backwards again and gone through it again. Politicians need to realise the impact it does have on extended family.”

Rita is one of more than 100,000 people who receive care funding from the NHS

Pat

Pat Lees laughs readily as she pushes a trolley around the supermarket. She leans on it to steady herself as she makes her way up and down the aisles of food, picking out the things she needs. It is October 2018, and Pat has just returned home after spending six months in hospital recuperating from two falls. John, a Red Cross volunteer, is alongside her, helping with her shopping.

Pat spots a jar of instant coffee, which she asks him to reach. “There’s one at the front that looks bigger, but it’s probably my eyesight,” she says. She is waiting for a cataract operation and a patch covers her left eye. “No, they are the same,” John responds.

She is one of an increasing number of older people who live alone. Her nearest family and close friends are more than 200 miles away.

“I’m hoping when we get to the end of the year and get my eye fixed and have proper glasses, that I shall be able to drive myself,” Pat says laughing. “I’m 84, but I’m still determined to get on with it properly.”

John will see Pat about three times and once the sessions are over she’ll be largely on her own. The last thing she or the health service want is for her to end up back in hospital.

In response to the pressures on the adult care system, the government has allowed local authorities to raise more money through council tax and provided extra short-terms funds. It’s often been targeted at getting people home from hospital to ease NHS pressures.

But experts in the field say it doesn’t allow councils to invest in the sort of preventative services that can pick problems up before people reach the sort of crisis that takes them to hospital in the first place.

In January 2019, we return to see Pat. The change from the woman walking determinedly around the supermarket is a shock. She speaks very quietly and is hard to hear. When she gets out of her chair to go to the kitchen she moves slowly, leaning much more heavily on her walking frame. She fell a few days before our visit. “I don’t want to fall,” she whispers. “It gets to a point where you are so off balance you actually do go down.”

She points to the spot in the kitchen where she landed. “I just suddenly went. And of course, when you go, there’s nothing you can do. You have to just go and wait for help.” She pressed the emergency button on a cord around her neck and help came fairly quickly, but she is clearly shaken.

Pat is paying for two one-hour visits from carers a week, but it isn’t enough. The charity, Age UK, estimates that there are 1.6 million people in the UK, who like Pat, don’t get enough help with their care. It estimates there are another 1.4 million people, who need support, but don’t get any.

The danger is that people become increasingly isolated. Certainly, Pat would like more company. “Occasionally, I feel like I’d like to see somebody, there isn’t anybody who can come,” she says.

“Mike, my neighbour, he died. It was terribly upsetting. I got on with Mike. We used to phone each other and chat.”

In the three months since leaving hospital and that early support finished, Pat seems to have dropped off nearly everyone’s radar and be heading towards a crisis. With her permission, we contacted the council’s social care team to ask them to look at her situation.

An appointment is made to see her and a couple of weeks later Hannah Croft, one of Somerset’s social workers, knocks on Pat’s door. It’s two in the afternoon and it takes a while for her to answer as she makes her way slowly and carefully along the hallway leaning on her walking frame. She’s still in her dressing gown.

Hannah asks her how she is getting on with preparing her meals.

“I do it myself, yes, it takes a bit of time.” Pat pauses for a minute, breathes heavily, then continues. “It wears me out.”

“Do you feel that you need any support on a daily basis?” Hannah asks.

“I doubt I’ll get that,” Pat replies. “I don’t think they do that kind of job.”

Hannah reassures her that it will be possible to get help each day, the question is whether Pat will pay for it herself or whether the council will fund it.

“Sorry to have to ask you this question,” says Hannah. “Do you have savings over £23,250?”

“No,” Pat replies.

It means that the council should pick up most of the bill for her care if her need for support is viewed as significant.

Later that day, Hannah is back in her office filling in the forms asking for help for Pat. The next step is to discuss the request with colleagues. If they agree with her assessment that Pat has a significant need for support, then funding will be approved.

“She inferred she could do so many things for herself and she wants to do so many things for herself,” Hannah says. “I would say that the evidence, the fact Pat was in her dressing gown in the middle of the day, indicates that maybe she needs just a little bit more support.”

A few weeks later, Pat is being visited by care staff twice a day. Hannah has also asked for a colleague to look at whether there are local lunch clubs or other activities that Pat might be interested in.

When we visit Pat again she is still frail, but pleased to be seeing people more often.

“I think to have someone calling on you helps a lot,” she says.

Pat is one of an estimated 1.6 million elderly people who do not receive enough support

Alan and Val

“I can tell you, if it wasn’t for these lifts there would be thousands more people in hospital,” says 74-year-old Alan Kinge as he presses the buttons to move an electric ceiling hoist along its tracks into position above his wife Val’s armchair, ready to lift her into a wheelchair. “She cannot live here without it. I can sometimes lift her three times a day, sometimes four.”

Val Kinge has multiple sclerosis, and her husband Alan is her main carer. Val says they “muddle along”. The couple met in 1965 and married two years later. Alan proudly shows off photos of Val at 18, on their wedding day and one taken 18 years ago.

They get two care visits a day, which are paid for by the council, but most of the time Alan copes on his own. He is one of about 5.5 million unpaid family carers in the UK. It’s been estimated that if you put a price tag on the informal care currently being provided, it would be worth somewhere between £57bn and a £100bn a year.

When you are caring for someone, we’re not on an eight-hour day, we’re on a 24-hour day

But if there isn’t enough back-up for carers, it’s all too easy to reach the point where you can no longer cope. “I had a scare about three years ago with heart problems,” Alan remembers. “The consultant’s report concluded I was technically all right with my heart. It was just sheer physical exhaustion.

“When you are caring for someone, we’re not on an eight-hour day, we’re on a 24-hour day. Non-negotiable. You can’t walk away, you can’t think I’ve had enough, I’m going to chuck in my notice on a Friday. You just have to get on with it.”

Research for the charity Carers UK shows that the impact on the economy as a whole is huge. It is estimated that one person in every seven in the workforce is caring for someone who is older, disabled or ill.

Alan and Val like to get out as much as they can. On a sunny day, they often head to the coast.

“You’ve got to go out. You’ve got to get away,” says Alan. “That’s the worst part about being disabled – being stuck at home.” Val agrees as he manoeuvres her wheelchair out of their adapted car and pushes her towards a picnic table that has stunning views of the sea and cliffs.

Alan points to others out enjoying the good weather. Many, like them, are over the age of 65. “One of the problems of the future is people that retire like to move down here away from the hustle and bustle of cities.

“You do need the help. It’s not an easy job,” he says, reflecting his worries about finding the care staff that he and Val rely on.

“The carer system is breaking down bit by bit because there is just not the money,” he says. “They can’t get the staff, they won’t work for the wages, and the hours. I’m not for a minute suggesting that the companies are trying to employ people on the cheap. I just think that if the money is not there, the government is not paying this money, what can you do?”

Successive governments have promised then failed to reform the funding of adult social care. Plans for the publication of the current government’s proposals, or green paper, have so far been delayed six times.

The government says it will set out “plans to reform the social care system at the earliest opportunity to ensure it is sustainable for the future".

The lack of a long-term plan worries Somerset’s director of adult social care, Stephen Chandler. “The green paper has been delayed and delayed and delayed,” he says. “And we pride ourselves on prevention and early intervention, which needs us to be able to plan longer term.”

Without a plan for the future he will continue to face really tough decisions. “This last year has been the hardest of my professional career, because I see ever more people for whom we are not providing the level and type of support that they want and need. Whilst we have improved a number of services, I’m conscious that has been at the cost of other services that people valued no longer being available.”

Alan Kinge has a blunter message for politicians of all parties. “In the next 10 years, it is going to be a really serious problem. Ignore it at the moment if you want, but it is going to be there as sure as day follows night.”

There are 5.6 million informal carers like Alan - of these, 1.3 million supply more than 50 hours of care a week